Creating Music of the Americas in the Cold War: Alberto Ginastera And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet

37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 K McGowan, James, Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet. Master of Music (Theory), August, 1995, 86 pp., 22 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 122 titles. This thesis presents an analysis of Copland's first major serial work, the Quartet for Piano and Strings (1950), using pitch-class set theory and tonal analytical techniques. The first chapter introduces Copland's Piano Quartet in its historical context and considers major influences on his compositional development. The second chapter takes up a pitch-class set approach to the work, emphasizing the role played by the eleven-tone row in determining salient pc sets. Chapter Three re-examines many of these same passages from the viewpoint of tonal referentiality, considering how Copland is able to evoke tonal gestures within a structural context governed by pc-set relationships. The fourth chapter will reflect on the dialectic that is played out in this work between pc-sets and tonal elements, and considers the strengths and weaknesses of various analytical approaches to the work. -

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

COURSE NAME: Latin and Caribbean Music

COURSE NAME: Latin and Caribbean Music COURSE NUMBER: MUS*139 CREDITS: 3 CATALOG DESCRIPTION: An introduction to the music of the diverse ethnic groups of the Caribbean and Latin America. The influence of Spain, Africa, Portugal, and other countries on the music of the region will be examined. In addition, the course will explore how the music of the Caribbean and Latin America has made a strong impact abroad. The study will also include how the elements of popular culture, dance, and folk music of the region are interrelated. PREREQUISITES: None COURSE OBJECTIVES: General Education Competencies Satisfied: HCC General Education Requirement Designated Competency Attribute Code(s): None Additional CSCU General Education Requirements for CSCU Transfer Degree Programs: None Embedded Competency(ies): None Discipline-Specific Attribute Code(s): ☒ FINA Fine Arts elective Course objectives: General Education Goals and Outcomes: None Course-Specific Outcomes: 1. Be familiar with the diverse cultures of the Caribbean and Latin America and be able to isolate their characteristics. MUS* E139 Date of Last Revision: April/2017 2. Learn what impact the music and customs of other countries has made on the region. 3. Know the interrelationship between music, art, dance, and other customs. 4. Know the musical instruments and music particular to each area. 5. Be familiar with the history of the region and know how it pertains to music. CONTENT: Introduction A. Overview of the Caribbean and Latin America Heritage of the Caribbean A. The Indian Heritage B. The African Heritage C. The European Heritage D. Other groups: Chinese and Syriansa Creolization A. What is meant by this term and how it affected music. -

Copyright by Bonny Kathleen Winston 2003

Copyright by Bonny Kathleen Winston 2003 The Development of a Multimedia Web Database for the Selection of 20th Century Intermediate Piano Repertoire by Bonny Kathleen Winston, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin May, 2003 Dedication This dissertation would not have been completed without all of the love and support from professors, family, and friends. To all of my dissertation committee for their support and help, especially John Geringer for his endless patience, Betty Mallard for her constant inspiration, and Martha Hilley for her underlying encouragement in all that I have done. A special thanks to my family, who have been the backbone of my music growth from childhood. To my parents, who have provided unwavering support, and to my five brothers, who endured countless hours of before-school practice time when the piano was still in the living room. Finally, a special thanks to my hall-mate friends in the school of music for helping me celebrate each milestone of this research project with laughter and encouragement and for showing me that graduate school really can make one climb the walls in MBE. The Development of a Multimedia Web Database for the Selection of 20th Century Intermediate Piano Repertoire Publication No. ________________ Bonny Kathleen Winston, D.M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2003 Supervisor: John M. Geringer The purpose of this dissertation was to create an on-line database for intermediate piano repertoire selection. -

5 Stages for Teaching Alberto Ginastera's Twelve American Preludes Qiwen Wan First-Year DMA in Piano Pedagogy University of South Carolina

5 Stages for Teaching Alberto Ginastera's Twelve American Preludes Qiwen Wan First-year DMA in Piano Pedagogy University of South Carolina Hello everyone, my name is Qiwen Wan. I am a first-year doctoral student in piano pedagogy major at the University of South Carolina. I am really glad to be here and thanks to SCMTA to allow me to present online under this circumstance. The topiC of my lightning talk is 5 stages for teaChing Alberto Ginastera's Twelve AmeriCan Preludes. First, please let me introduce this colleCtion. Twelve AmeriCan Preludes is composed by Alberto Ginastera, who is known as one of the most important South AmeriCan composers of the 20th century. It was published in two volumes in 1944. In this colleCtion, there are 12 short piano pieCes eaCh about one minute in length. Every prelude has a title, tempo and metronome marking, and eaCh presents a different charaCter or purpose for study. There are two pieCes that focus on a speCifiC teChnique, titled Accents, and Octaves. No. 5 and 12 are titled with PentatoniC Minor and Major Modes. Triste, Creole Dance, Vidala, and Pastorale display folk influences. The remaining four pieCes pay tribute to other 20th-Century AmeriCan composers. This set of preludes is an attraCtive output for piano that skillfully combines folk Argentine rhythms and Colors with modern composing teChniques. Twelve American Preludes is a great contemporary composition for late-intermediate to early-advanced students. In The Pianist’s Guide to Standard Teaching and Performing Literature, Dr. Jane Magrath uses a 10-level system to list the pieCes from this colleCtion in different levels. -

Alberto Ginastera En Wikipedia

Alberto Ginastera en Wikipedia http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alberto_Ginastera Alberto Ginastera video photos / fotos (sitio compositores & Intérpretes) http://www.ciweb.com.ar/Ginastera/ Biografia Nació en Buenos Aires, Argentina, el 11 de abril de 1916. Murió en Ginebra, Suíza, el 25 de junio de 1983. Su primer trabajo importante fue el ballet Penambí, que lo hizo conocido en toda Argentina. De 1945 a 1948 abandona su país debido a su pésima relación con Perón. Va para Estados Unidos, donde estudia con Copland y Tanglewood. Cerca de 1956 expande su estilo musical más allá de los límites de la nacionalidad. Es la época de excelentes trabajos. En 1969 sale nuevamente de Argentina y va a vivir en Ginebra, Suíza. Su música es esencialmente tradicionalista. Una ecléctica síntesis de técnicas de varias escuelas musicales está evidente en su composición más famosa, la ópera Bomarzo. Quedó famoso como compositor de fuerte sentimiento nacionalista, a pesar de haber influencias de la música internacional que se producía en Europa después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Su obra puede ser dividida en 3 períodos: nacionalismo objetivo, nacionalismo subjetivo y neo-expresionismo. Sus primeros trabajos pertenecen al primer período. Él caracterizó ese período como una etapa de "nacionalismo objetivo" en el cual las características de la música folklórica se reproducían abiertamente. Usa el folklore argentino y es influenciado por Stravinsky, Bartok y Falla. Son de este período: Danzas Argentinas op. 2 para piano, Estancia (ballet), las Cinco Canciones Populares Argentinas, Las horas de una estancia y Pampeana nº 1. El estreno de la suite orquestal de su ballet Estancia, consolidó su posición dentro de Argentina. -

COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, and PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice

Blurring the Border: Copland, Chávez, and Pan-Americanism Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Sierra, Candice Priscilla Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 23:10:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/634377 BLURRING THE BORDER: COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, AND PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice Priscilla Sierra ________________________________ Copyright © Candice Priscilla Sierra 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Musical Examples ……...……………………………………………………………… 4 Abstract………………...……………………………………………………………….……... 5 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Chapter 1: Setting the Stage: Similarities in Upbringing and Early Education……………… 11 Chapter 2: Pan-American Identity and the Departure From European Traditions…………... 22 Chapter 3: A Populist Approach to Politics, Music, and the Working Class……………....… 39 Chapter 4: Latin American Impressions: Folk Song, Mexicanidad, and Copland’s New Career Paths………………………………………………………….…. 53 Chapter 5: Musical Aesthetics and Comparisons…………………………………………...... 64 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………. 82 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………….. 85 4 LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES Example 1. Chávez, Sinfonía India (1935–1936), r17-1 to r18+3……………………………... 69 Example 2. Copland, Three Latin American Sketches: No. 3, Danza de Jalisco (1959–1972), r180+4 to r180+8……………………………………………………………………...... 70 Example 3. Chávez, Sinfonía India (1935–1936), r79-2 to r80+1…………………………….. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 83,1963-1964, Trip

BOSTON • r . SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY /'I HENRY LEE HIGGINSON TUESDAY EVENING 4 ' % mm !l SERIES 5*a ?^°£D* '^<\ -#": <3< .4) \S? EIGHTY-THIRD SEASON 1963-1964 TAKE NOTE The precursor of the oboe goes back to antiquity — it was found in Sumeria (2800 bc) and was the Jewish halil, the Greek aulos, and the Roman tibia • After the renaissance, instruments of this type were found in complete families ranging from the soprano to the bass. The higher or smaller instruments were named by the French "haulx-bois" or "hault- bois" which was transcribed by the Italians into oboe which name is now used in English, German and Italian to distinguish the smallest instrument • In a symphony orchestra, it usually gives the pitch to the other instruments • Is it time for you to take note of your insurance needs? • We welcome the opportunity to analyze your present program and offer our professional service to provide you with intelligent, complete protection. invite i . We respectfully* your inquiry , , .,, / Associated with CHARLES H. WATKINS CO. & /qbrioN, RUSSELL 8c CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton / 147 milk street boston 9, Massachusetts/ Insurance of Every Description 542-1250 EIGHTY-THIRD SEASON, 1963-1964 CONCERT BULLETIN OF THE Boston Symphony Orchestra ERICH LEINSDORF, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Talcott M. Banks Vice-President Richard C. Paine Treasurer Abram Berkowitz Henry A. Laughlin Theodore P. Ferris John T. Noonan Francis W. Hatch Mrs. -

Alberto Ginastera

FUNDACION JUAN MARCH HOMENAJE A Alberto Ginastera Miércoles, 20 de abril de 1977, 20 horas. PROGRAMA ALBERTO GINASTERA. Quihteto para piano y cuarteto de cuerdas, Op. 29 (1963). I. Introduzione. II. Cadenza I per viola e violoncello. III. Scherzo Fantastico. IV. Cadenza II per due violini. V. Piccola musica notturna. VI. Cadenza III per pianoforte. VII. Finale. ALBERTO GINASTERA. Serenata sobre los «Poemas de amor», de Neruda, Op. 42 (1974). I. Poetico. II. Fantastico. III. Drammatico. Violoncello: Aurora Nàtola. Baritono: Antonio Blancas. Grupo Koan Director: Julio Malaval. NOTAS AL PROGRAMA QUINTETO Para piano y cuarteto de cuerdas, Op. 29 El «Quinteto» Op. 29 me fue encargado por la señora Jeannette Arata de Erize, presidente del Mozarteum Argentino, con destino al Quinteto Chigiano de Siena, quien estrenó la obra ei 13 de abril de 1963 en el teatro La Fenice de Venecia durante el Festival de Música Contemporánea que se realizaba en dicha ciudad. En este «Quinteto», como lo señalaron algunos mu- sicólogos estudiosos de mi obra, se manifiestan cla- ramente algunas de mis preocupaciones más anhe- lantes en el campo de la creación musical: la elabo- ración de un lenguaje personal en su textura, la bús- queda de nuevas estructuras que se acomoden al idioma sonoro actual y la adaptación del discurso musical a un procedimiento de escritura basado en el máximo empleo de las posibilidades de los instru- mentos y en el realce del virtuosismo de los intérpre- tes. Los movimientos tradicionales de las obras de cá- mara que respondían a las exigencias de la música tonal están aquí reemplazados por cuatro estructuras que conservan el carácter del allegro, scherzo, ada- gio y final, pero cuya forma está dada por los proce- dimientos derivados de la técnica «post-serial». -

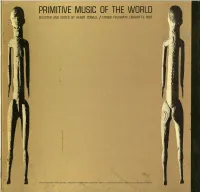

PRIMITIVE MUSIC of the WORLD Selected and Edited by Henry Cowell

ETHNIC FOLKWAYS LIBRARY Album # FE 4581 ©1962 by Folkways Records & Service Corp., 121 W. 47th St. NYC USA PRIMITIVE MUSIC OF THE WORLD Selected and Edited by Henry Cowell by Henry Cowell Usually, however, there are two, three, four or five different tones used in primitive melodies. Some peoples in different parts of the world live These tones seem to be built up in relation to under more primitive conditions than others, one another in two different ways; the most and in many cases their arts are beginning common is that the tones should be very close points. In the field of the art of sound there is together - a 1/2 step or closer, never more than a whole step. This means that the singer great variety to be found; no two people I s music is alike, and in some cases there is much com tenses or relaxes the vocal cords as little as plexity. In no case is it easy for an outsider to possible; instruments imitate the voice. The imitate, even when it seems very simple. other method of relationship seems to be de rived from instruments, and is the result of While all music may have had outside influence over-blowing on pipes, flutes, etc. From this at one time, we think of music as being primi is de.rived wide leaps, the octave, the fifth tive if no outside influence can be traced, or in and the fourth. These two ways are sometimes some cases where there is some influence from combined (as in cut #2 of flutes from New other primitive sources. -

Bomarzo - Opera En 2 Actos Y 15 Cuadros

Bomarzo - Opera en 2 actos y 15 cuadros Alberto Ginastera Libreto de Manuel Mujica Láinez Basada en su novela homónima del escritor Obra encargada por Hobart Spalding, presidente de la Opera Society de Washington. Estrenado: 19 mayo 1967, Washington DC, Lisner Auditorium, con dirección de Julius Rudel, Regie de Tito Cappobianco. Intérpretes: Salvador Novoa, Isabel Penagos, Joanna Simon, Claramae Turner. Estreno Sudamericano, Teatro Colón, 1972 El argumento narra la vida de Pier Francesco Orsini, duque de Bomarzo, perteneciente a una noble familia romana, de cuya historia real existen pocos datos y por esto mismo resulta el personaje ideal para ser recreado por el escritor Manuel Mujica Láinez (1910-1984) que le da una nueva vida, literaria pero verosímil, rescatándolo así del anonimato. El protagonista da pie para evocar a toda una serie de personajes históricos que componen un impresionante fresco del Renacimiento italiano tardío, el del siglo XVI, conocido allí como“cinquecento”. Siglo XVI. El Duque de Bomarzo, Pier Francesco Orsini, cuyo aspecto y pecados se reflejan en las figuras de piedra en su jardín, bebe una poción para conseguir la inmortalidad, pero es envenenado. Ve pasar distintos episodios de su vida pasada, su infancia despreciada, su horóscopo siniestro, su unión con una cortesana, la provocación de su padre, su fracaso al tratar de salvar a su hermano de la muerte en el Tiber, y en consecuencia, su reinado como Duque, con sus celos y asesinatos. Ambientada en la Italia renacentista es una minuciosa reconstrucción del ambiente que dominaba aquel entonces en el mundo de los condottieri, prelados, artistas y hombres del pueblo. -

THE EXPEDITIONS of the VICTOR TALKING MACHINE COMPANY THROUGH LATIN AMERICA, 1903-1926 a Dissertation

RECORDING STUDIOS ON TOUR: THE EXPEDITIONS OF THE VICTOR TALKING MACHINE COMPANY THROUGH LATIN AMERICA, 1903-1926 A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Sergio Daniel Ospina Romero May 2019 © 2019 Sergio Daniel Ospina Romero ii RECORDING STUDIOS ON TOUR: THE EXPEDITIONS OF THE VICTOR TALKING MACHINE THROUGH LATIN AMERICA, 1903-1926 Sergio Daniel Ospina Romero, PhD Cornell University, 2019 During the early twentieth century, recording technicians travelled around the world on behalf of the multinational recording companies. Producing recordings with vernacular repertoires not only became an effective way to open local markets for the talking machines that these same companies were manufacturing. It also allowed for an unprecedented global circulation of local musics. This dissertation focuses on the recording expeditions lead by the Victor Talking Machine Company through several cities in Latin America during the acoustic era. Drawing from untapped archival material, including the daily ledgers of the expeditions, the following pages offer the first comprehensive history of these expeditions while focusing on five areas of analysis: the globalization of recorded sound, the imperial and transcultural dynamics in the itinerant recording ventures of the industry, the interventions of “recording scouts” for the production of acoustic records, the sounding events recorded during the expeditions, and the transnational circulation of these recordings. I argue that rather than a marginal side of the music industry or a rudimentary operation, as it has been usually presented hitherto in many histories of the phonograph, sound recording during the acoustic era was a central and intricate area in the business; and that the international ventures of recording companies before 1925 set the conditions of possibility for the consolidation of iii media entertainment as a defining aspect of consumer culture worldwide through the twentieth century.