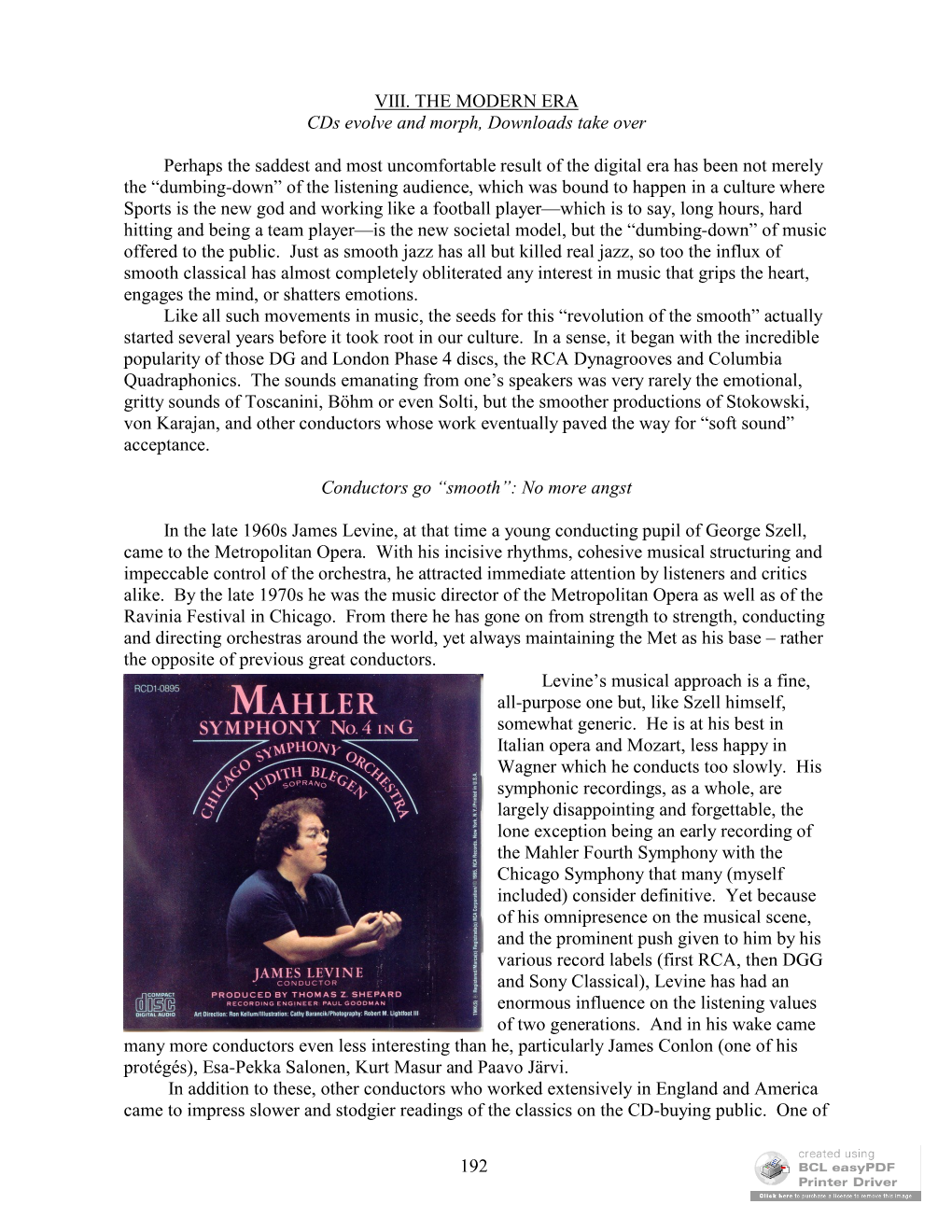

Spinning the Record the Most Insidious Was Reginald Goodall, Whose “Wagner-In-English” Recordings of the 1970S Had an Enormous Impact on the Emerging Cultural Scene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Katalog EMI Classics Oraz Virgin Classics

Katalog EMI Classics oraz Virgin Classics Tytuł: Vinci L'Artaserse ICPN: 5099960286925 KTM: 6028692 Data Premiery: 01.10.2012 Data nagrania: styczeń 2012 Main Artists: Diego Fasolis/Philippe Jaroussky/Max Emanuel Cencic/Franco Fagioli/Valer Barna-Sabadus/Yuriy Mynenko/Daniel Behle/Coro della Radiotelevisione svizzera, Lugano/Concerto Köln Kompozytor: Leonardo Vinci 3 CD POLSKA PREMIERA Tytuł: Feelhermony ICPN:5099901770827 KRM:0177082 Data Premiery: 09.10.2012 Data Nagrania: 2012 Main Artists: KROKE, Sinfonietta Cracovia, Anna Maria Jopek, Sławek Berny Kompozytor: KROKE Aranżancje: Krzysztof Herdzin 1 CD Tytuł: Rodgers & Hammerstein at the Movies ICPN: 5099931930123 KTM: 3193012 Data Premiery: 01.10.2012 Data nagrania: styczeń 2012 Main Artists: John Wilson, John Wilson Orchestra, Sierra Boggess, Anna Jane Casey, Joyce DiDonato, Maria Ewing, Julian Ovenden, David Pittsinger, Maida Vale Singers Kompozytor: Rodgers & Hammerstein 1 CD Tytuł: Sound the Trumpet - Royal Music of Purcell and Handel ICPN: 5099944032920 KTM: 4403292 Data Premiery: 15.10.2012 Data nagrania: styczeń 2012 Main Artists: Alison Balsom, The English Concert, Pinnock Trevor Kompozytor: Purcell, Haendel 1 CD Tytuł: Dvorak: Symphony No.9 & Cello Concerto ICPN: 5099991410221 KTM: 9141022 Data Premiery: 08.10.2012 Data Nagrania: styczeń 2012 Main Artists: Antonio Pappano Kompozytor: Antonin Dvorak 2 CD Tytuł: Drama Queens ICPN: 5099960265425 KTM: 6026542 Data Premiery: 01.10.2012 Main Artists: Joyce DiDonato/Il Complesso Barocco/Alan Curtis Kompozytor: Various Artists 1 CD -

Simfonies 1, 2, 3, 4 JORDI SAVALL

Simfonies 1, 2, 3, 4 JORDI SAVALL "An impressive recording" "Jordi Savall démontre une The Classic Review compréhension profonde du massif beethovénien ; il en révèle les équilibres singuliers” Classique News "L'enregistrement de l'année de Beethoven" MERKUR "It’s the organic nature of Savall’s conception that makes it stand head and shoulders above this year’s crop of Fifths" Limelight, EDITOR'S CHOICE "La perfección en estas grabaciones es difícil de comentar. La música está viva y coleando" POLITIKEN "A really first-class recording" Classical Candor 10/2/2021 Review | Gramophone BEETHOVEN Symphonies Nos 1-5 (Savall) Follow us View record and artist details Author: Peter Quantrill We know a lot about how Beethoven composed at the keyboard, and right from the clipped, slashed and rolled tutti chords of the First Symphony’s opening-movement Allegro, all weighted according to context by Le Concert des Nations, there’s a fine and rare sense of how his thinking transferred itself to an orchestral canvas. Made under studio conditions in the church of a medieval Catalonian fortress, these recordings BEETHOVEN enjoy plenty of string bass colour and timpani impact without Symphonies Nos 1-5 swamping the liveliest inner-part debates between solo winds (Savall) or divided-violin combat. Symphony No. 1 ‘Enjoy’ is the word for the set as a whole. The tempos are largely Beethoven’s own, at least according to the metronome Symphony No. 2 marks he retrospectively applied in 1809 to all the symphonies Symphony No. 3, he had composed up to that point, but almost no 'Eroica' interpretative decision feels insisted upon, no expressive horizon foreshortened by a ready-made frame. -

'Boxing Clever

NOVEMBER 05 2018 sandboxMUSIC MARKETING FOR THE DIGITAL ERA ISSUE 215 ’BOXING CLEVER SANDBOX SUMMIT SPECIAL ISSUE Event photography: Vitalij Sidorovic Music Ally would like to thank all of the Sandbox Summit sponsors in association with Official lanyard sponsor Support sponsor Networking/drinks provided by #MarketMusicBetter ast Wednesday (31st October), Music Ally held our latest Sandbox Summit conference in London. While we were Ltweeting from the event, you may have wondered why we hadn’t published any reports from the sessions on our site and ’BOXING CLEVER in our bulletin. Why not? Because we were trying something different: Music Ally’s Sandbox Summit conference in London, IN preparing our writeups for this special-edition sandbox report. From the YouTube Music keynote to panels about manager/ ASSOCIATION WITH LINKFIRE, explored music marketing label relations, new technology and in-house ad-buying, taking in Fortnite and esports, Ed Sheeran, Snapchat campaigns and topics, as well as some related areas, with a lineup marketing to older fans along the way, we’ve broken down the key views, stats and debates from our one-day event. We hope drawn from the sharp end of these trends. you enjoy the results. :) 6 | sandbox | ISSUE 215 | 05.11.2018 TALES OF THE ’TUBE Community tabs, premieres and curation channels cited as key tools for artists on YouTube in 2018 ensions between YouTube and the music industry remain at raised Tlevels following the recent European Parliament vote to approve Article 13 of the proposed new Copyright Directive, with YouTube’s CEO Susan Wojcicki and (the day after Sandbox Summit) music chief Lyor Cohen both publicly criticising the legislation. -

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Fall Quarter 2018 (October - December) 1 A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

AP1 Companies Affiliates

AP1 COMPANIES & AFFILIATES 100% RECORDS BIG MUSIC CONNOISSEUR 130701 LTD INTERNATIONAL COLLECTIONS 3 BEAT LABEL BLAIRHILL MEDIA LTD (FIRST NIGHT RECORDS) MANAGEMENT LTD BLIX STREET RECORDS COOKING VINYL LTD A&G PRODUCTIONS LTD (TOON COOL RECORDS) LTD BLUEPRINT RECORDING CR2 RECORDS ABSOLUTE MARKETING CORP CREATION RECORDS INTERNATIONAL LTD BOROUGH MUSIC LTD CREOLE RECORDS ABSOLUTE MARKETING BRAVOUR LTD CUMBANCHA LTD & DISTRIBUTION LTD BREAKBEAT KAOS CURB RECORDS LTD ACE RECORDS LTD BROWNSWOOD D RECORDS LTD (BEAT GOES PUBLIC, BIG RECORDINGS DE ANGELIS RECORDS BEAT, BLUE HORIZON, BUZZIN FLY RECORDS LTD BLUESVILLE, BOPLICITY, CARLTON VIDEO DEAGOSTINI CHISWICK, CONTEMPARY, DEATH IN VEGAS FANTASY, GALAXY, CEEDEE MAIL T/A GLOBESTYLE, JAZZLAND, ANGEL AIR RECS DECLAN COLGAN KENT, MILESTONE, NEW JAZZ, CENTURY MEDIA MUSIC ORIGINAL BLUES, BLUES (PONEGYRIC, DGM) CLASSICS, PABLO, PRESTIGE, CHAMPION RECORDS DEEPER SUBSTANCE (CHEEKY MUSIC, BADBOY, RIVERSIDE, SOUTHBOUND, RECORDS LTD SPECIALTY, STAX) MADHOUSE ) ADA GLOBAL LTD CHANDOS RECORDS DEFECTED RECORDS LTD ADVENTURE RECORDS LTD (2 FOR 1 BEAR ESSENTIALS, (ITH, FLUENTIAL) AIM LTD T/A INDEPENDENTS BRASS, CHACONNE, DELPHIAN RECORDS LTD DAY RECORDINGS COLLECT, FLYBACK, DELTA LEISURE GROPU PLC AIR MUSIC AND MEDIA HISTORIC, SACD) DEMON MUSIC GROUP AIR RECORDINGS LTD CHANNEL FOUR LTD ALBERT PRODUCTIONS TELEVISON (IMP RECORDS) ALL AROUND THE CHAPTER ONE DEUX-ELLES WORLD PRODUCTIONS RECORDS LTD DHARMA RECORDS LTD LTD CHEMIKAL- DISTINCTIVE RECORDS AMG LTD UNDERGROUND LTD (BETTER THE DEVIL) RECORDS DISKY COMMUNICATIONS -

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

THE CLEVELAN ORCHESTRA California Masterwor S

����������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������������������������������������� �������� ������������������������������� ��������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ����������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������������ ���������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������� ������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������� ������������� ������ ������������� ��������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� ����������� �������������������������������� ����������������� ����� �������� �������������� ��������� ���������������������� Welcome to the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Orchestra’s performances in the museum California Masterworks – Program 1 in May 2011 were a milestone event and, according to the Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland Museum of Art Plain Dealer, among the year’s “high notes” in classical Wednesday evening, May 1, 2013, at 7:30 p.m. music. We are delighted to once again welcome The James Feddeck, conductor Cleveland Orchestra to the Cleveland Museum of Art as this groundbreaking collaboration between two of HENRY COWELL Sinfonietta -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-Q (Mark One) x QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the quarterly period ended June 30, 2013 OR ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission File Number 001-32502 Warner Music Group Corp. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 13-4271875 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 75 Rockefeller Plaza New York, NY 10019 (Address of principal executive offices) (212) 275-2000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit and post such files). Yes x No ¨ Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer or a smaller reporting company. -

Visite Par Audioguide Des Dominicains

STATION - WELCOME BY BRIGITTE KLINKERT Hello, my name is Neil Beardmore and on behalf on Brigitte Klinkert, president of the association that manages this heritage site, which is listed as a historic monument, welcome to The Dominican Convent of Haut-Alsace. The Dominican convent is no longer a place of worship. It is now a cultural centre, certified by the French Culture Ministry as a Subsidised Music Performance Centre. The Dominican Convent of Haute-Alsace belongs to the Haut-Rhin County Council, and it is one of the most important sites of the Upper Rhine Region, together with Hohlandsbourg Castle, Wesserling Park and the Ecomusée d’Alsace, all three of which are nearby. Here you are at the Dominican Convent, a place with an extraordinary history where, if time had stood still, friar preachers, fishmongers, textile workers and the great Rostropovich would meet. To begin this tour, please make your way over to the cloister, which was once a place of prayer and contemplation. We recommend that you follow the tour in the suggested direction, because you will find markers corresponding to the chapter numbers of your audio-guide. Be curious, listen carefully and enjoy your tour of the Dominican Convent. STATION - CLOISTER The sandstone of the Vosges Mountains is whispering... Listen closely and it will tell you seven hundred years of history. This cloister is part of a former Dominican convent, where friar preachers lived. The mendicant order was composed of friars who lived in cities to preach and who relied on charity to survive. It was founded in Toulouse in the early 13th century by St. -

Classical Series 1 2019/2020

classical series 2019/2020 season 1 classical series 2019/2020 Meet us at de Doelen! Bang in the middle of Rotterdam’s vibrant city centre and at a stone’s throw from the magnificent Central Station, you find concert hall de Doelen. A perfect architectural example of the Dutch post-war reconstruction era, as well as a veritable people’s palace, featuring international programming and festivals. Built in the sixties, its spacious state- of-the-art auditoria and foyers continue to make it look and feel like a timelessly modern and dynamic location indeed. De Doelen is home to the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, with the very young and talented conductor Lahav Shani at its helm. But that is not all! With over 600 concerts held annually, our programming is delightfully varied, ranging from true crowd-pullers to concerts catering to connoisseurs, and from children’s concerts to performances of world music, jazz and hip-hop. What’s more, de Doelen is the beating heart of renowned cultural festivals such as the IFFR, Poetry International, Rotterdam Unlimited, HipHopHouse’s Make A Scene and RPhO’s Gergiev Festival. Check this brochure for this season’s programme. You will hopefully be as thrilled as we are with what’s on offer. Meet us at de Doelen and enjoy! Janneke Staarink, director & de Doelen team Janneke Staarink © Sanne Donders classical series 3 contents classical series 2019/2020 season preface 3 Pierre-Laurent Aimard © Marco Borggreve Grupo Ruta de la Esclavitud © Claire Xavier classical series 6 - 29 suggestions per subject 30 chronological overview 32 piano great baroque ordering information 36 From classics to cross-overs: the versatility of the This series features great themes and signature baroque floor plans 38 piano takes centre stage. -

The Quadraphonic Sound of Pink Floyd: a Brief History

THE QUADRAPHONIC SOUND OF PINK FLOYD: A BRIEF HISTORY 1: 1967 – The Azimuth CoorDinator. A quaD panning Device that featured two panning joysticks in a large metal box, it was built in 1967 by Abbey RoaD sounD engineer Bernard Speight and used for the Floyd’s Games For May show at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall. It was stolen after the show. 1969 – Its replacement, a seconD Azimuth Coordinator, was first used at a Royal Festival Hall concert in 1969. It was also useD by recorD proDucer Alan Parsons during the recording of Dark Side of the Moon (an album which was issueD in both stereo and quadraphonic versions). This device is now on display in the Victoria & Albert Museum in LonDon. 2. 1972 – British pro auDio manufacturer Allen & Heath is commissioneD to builD the MoD1. This quad console was built for Pink Floyd’s live use around 1972 and can be seen in their film Live in Pompeii. This was subsequently sold and is thought to have endeD up in a lock-up garage in North London. 3. 1973 – Allen & Heath built a seconD quaD boarD in 1973. This was useD for the 1974 Winter Tour. Its whereabouts are unknown. 4. 1977 – Another British pro auDio manufacturer, MiDas, builDs a pair of ‘mirror’ PF1 consoles (so calleD because they exactly mirror each other’s facilities). These were baseD on the MiDas Pro4 console design. They had input and output sections and could be used as stand-alone consoles. They fed signals into a central, specially designed quad routing box, and were used on the 1977 In The Flesh (Animals) tour. -

Disques D'or 2009

SINGLES OR 2009 (150 000 exemplaires vendus) DATE DE DATE DE TITRES EDITEUR PRODUCTEUR ARTISTES SORTIE CONSTAT MERCURY J'AIMERAIS TELLEMENT 05/10/2009 22/12/2009 JENA UNIVERSAL MUSIC France SQUARE RIVOLI PUBLISHING EMI WHEN LOVE TAKES OVER 12/06/2009 21/12/2009 DAVID GUETTA MUSIC France SQUARE RIVOLI PUBLISHING EMI SEXY BITCH 28/08/2009 21/12/2009 DAVID GUETTA MUSIC France SQUARE RIVOLI PUBLISHING EMI BABY WHEN THE LIGHT 12/10/2007 21/12/2009 DAVID GUETTA MUSIC France EMI RECORDS LTD FUCK YOU 10/07/2009 21/12/2009 LILLY ALLEN EMI MUSIC France CAPITOL RECORDS EMI I KISSED A GIRL 22/08/2009 21/12/2009 KATY PERRY MUSIC France SINGLES PLATINE 2009 (250 000 exemplaires vendus) DATE DE DATE DE TITRES EDITEUR PRODUCTEUR ARTISTES SORTIE CONSTAT SPECIAL MARKETING SONY CA M'ENERVE 16/03/2009 22/10/2009 HELMUT FRITZ BMG ALBUMS OR (50 000 ex.) POLYDOR ABBA THE DEFINITIVE COLLECTION 31/08/2009 21/12/2009 UNIVERSAL MUSIC France POLYDOR ABD AL MALIK DANTE 03/11/2008 05/02/2009 UNIVERSAL MUSIC France JIVE EPIC THE ELEMENT OF FREEDOM 11/12/2009 15/12/2009 ALICIA KEYS SONY BMG WARNER AMAURY VASSILI VINCERO 23/03/2009 24/06/2009 WARNER MUSIC France JIVE EPIC OU JE VAIS 04/12/2009 15/12/2009 AMEL BENT SONY BMG POLYDOR ANAIS THE LOVE ALBUM 10/11/2008 05/02/2009 UNIVERSAL MUSIC France POLYDOR ANDRE RIEU PASSIONNEMENT 24/11/2008 05/02/2009 UNIVERSAL MUSIC France POLYDOR ANDRE RIEU A TOI 16/11/2009 21/12/2009 UNIVERSAL MUSIC France ASSASSIN PRODUCTION EMI ASSASSIN TOUCHE D'ESPOIR 27/03/2000 30/07/2009 MUSIC France WARNER NICO TEEN LOVE 16/11/2009 10/12/2009 B B BRUNES WARNER MUSIC France WEA B.O.F.