The Sherry River Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moutere Gravels

LAND USE ON THE MOUTERE GRAVELS, I\TELSON, AND THE DilPORTANOE OF PHYSIC.AL AND EOONMIC FACTORS IN DEVJt~LOPHTG THE F'T:?ESE:NT PATTERN. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS ( Honours ) GEOGRAPHY UNIVERSITY OF NEW ZEALAND 1953 H. B. BOURNE-WEBB.- - TABLE OF CONTENTS. CRAFTER 1. INTRODUCTION. Page i. Terminology. Location. Maps. General Description. CH.AFTER 11. HISTORY OF LAND USE. Page 1. Natural Vegetation 1840. Land use in 1860. Land use in 1905. Land use in 1915. Land use in 1930. CHA.PrER 111. PRESENT DAY LAND USE. Page 17. Intensively farmed areas. Forestry in the region. Reversion in the region. CHA.PrER l V. A NOTE ON TEE GEOLOGY OF THE REGION Page 48. Geological History. Composition of the gravels. Structure and surface forms. Slope. Effect on land use. CHA.mm v. CLIMATE OF THE REGION. Page 55. Effect on land use. CRAFTER Vl. SOILS ON Tlffi: MGm'ERE GRAVELS. Page 59. Soil.tYJDes. Effect on land use. CHAPrER Vll. ECONOMIC FACTORS WrIICH HAVE INFLUENCED TEE LAND USE PATTERN. Page 66. ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS. ~- After page. l. Location. ii. 2. Natu.ral Vegetation. i2. 3. Land use in 1905. 6. Land use regions and generalized land use. 5. Terraces and sub-regions at Motupiko. 27a. 6. Slope Map. Folder at back. 7. Rainfall Distribution. 55. 8. Soils. 59. PLATES. Page. 1. Lower Moutere 20. 2. Tapawera. 29. 3. View of Orcharding Arf;;a. 34a. 4. Contoured Orchard. 37. 5. Reversion and Orchards. 38a. 6. Golden Downs State Forest. 39a. 7. Japanese Larch. 40a. B. -

Newsletter 26Th October 2018.Pub

Murchison Area School 61 Waller Street P O Box 73 Murchison 7049 Phone 03 5239 072 [email protected] 26th October 2018 Term 4 School Wide Value — Consideration Kia ora, Moghrey Mie, I have spoken in recent weeks about our ERO (Education Review Office) report that we had last term. The final report has now been published and is an official document for all to see. I have placed this on our school website (www.murchison.school.nz ). It can also be found on the ERO website at www.ero.govt.nz . The following are some extracts from the report: 1) “Respectful and caring relationships contribute to equitable and successful outcomes for students. Students learn in a settled and supportive learning environment. Teachers know students very well as individuals and as learners and focus on their holistic wellbeing and academic success. Individual students’ learning is well tracked and monitored by classroom teachers. The school and wider community work closely to support and enrich students’ learning.” 2) “Students who need extra assistance to succeed are very well supported. There are improved systems to effectively identify, monitor and support these students. The school works constructively with parents and experts beyond the school to find solutions to improve student outcomes at home and at school. Students with additional learning needs benefit from well -considered individual learning plans and are supported towards full inclusion.” 3) “The vision, values and priorities that underpin the school’s culture and curriculum are well known and evident in practice. This includes restorative practices and growth mindset approaches.The school’s valued outcomes for students are regularly shared to build and embed understanding. -

Car Company Nelson U7 2018

Car Company Nelson U7 2018 Draw dated 3/5/18 Game times are posted on the Monday prior on our website http://www.tasmanrugby.co.nz/draws-results/juniorage-grade Date Home Away Venue Week 1 5/5/2018 Tapawera: U7 V Murchison: U7 Tapawera 5/5/2018 Rangers: U7 V Riwaka: Aqua Taxi U7 Black Upper Moutere 5/5/2018 Wanderers: U7 Gold V Waimea Old Boys: U7 Griffins Lord Rutherford Park 5/5/2018 Wanderers: U7 Stripes V Riwaka: Aqua Taxi U7 White Lord Rutherford Park 5/5/2018 Wanderers: U7 Blue V Waimea Old Boys: U7 Mako Lord Rutherford Park 5/5/2018 Nelson: U7 Blue V Nelson: U7 White Neale Park 5/5/2018 Waimea Old Boys: U7 Red V Huia: U7 Jubilee Park 5/5/2018 Waimea Old Boys: U7 White V Stoke: U7 White Jubilee Park 5/5/2018 Marist: U7 V Stoke: U7 Red Tahunanui Week 2 12/5/2018 Wanderers: U7 Stripes V Murchison: U7 Lord Rutherford Park 12/5/2018 Wanderers: U7 Gold V Riwaka: Aqua Taxi U7 Black Lord Rutherford Park 12/5/2018 Wanderers: U7 Blue V Riwaka: Aqua Taxi U7 White Lord Rutherford Park 12/5/2018 Stoke: U7 Red V Waimea Old Boys: U7 Red Greenmeadows 12/5/2018 Rangers: U7 V Tapawera: U7 Upper Moutere 12/5/2018 Huia: U7 V Waimea Old Boys: U7 Griffins Sports Park Motueka 12/5/2018 Nelson: U7 White V Waimea Old Boys: U7 White Neale Park 12/5/2018 Nelson: U7 Blue V Marist: U7 Neale Park 12/5/2018 Stoke: U7 White V Waimea Old Boys: U7 Mako Greenmeadows Week 3 19/5/2018 Tapawera: U7 V Wanderers: U7 Stripes Tapawera 19/5/2018 Murchison: U7 V Wanderers: U7 Blue Murchison 19/5/2018 Waimea Old Boys: U7 Griffins V Stoke: U7 Red Jubilee Park 19/5/2018 Waimea -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 79

2002 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 79 NELSON CONSERVANCY-Continued Reg. Operator Postal Address Location of Mill No. 303 Baigent, H., and Sons Ltd. P.O. Box 97, Nelson .. Wakefield 221 Barnes, T. H., and Co. Ltd. Murphy's Road, Blenheim Okoha 155 Bastin, W., and Sons Edward Street, Wakefield Maud Creek 112 Benara Timber Co. Ltd. P.O. Box 10, Nelson .. Mangarakau 199 Blackadder, W. D. .. Rahu, Reefton Rahu 152 Brown Creek Sawmilling Co. Ltd. P.O. Box 14, Ikamatua Ikamatua 286 Bruning, N. C. R.M.D., Takaka Waitapu 290 Bryant Bros. P.O. Box 240, Blenheim Canvastown 8 Chamberlain Construction Ltd. P.O. Box 291, Nelson Korere 161 Chandler Bros. Care of P.O. Box 63, Westport Mokihinui 229 Couper Bros. Rai Valley Marlborough Rai Valley 213 Crispin, A. C. R. Havelock .. Havelock 178 Cronadun Timbers Ltd. P.O. Box 234, Greymouth Larry's Creek (1) 24 De Boo Bros. Rai Valley .. Carluke 156 Deck Bros. Riwaka R.M.D. 3, Motueka Riwaka 173 Donnelly Milling Co. Ltd. Care of P.O. Box 10, Nelson " Hope 277 Duncan, J. W. C. and N. H. Tapawera R.D. 2, Wakefield .. Tapawera 200 Eggers, R. T., and Sons Ltd. R.D. No.2, Upper Moutere, Nelson Harakeke 282 Farrington, L. and M. Mistlands, Tutaki R.D., Murchison Tutaki 292 Fleming Bros. Howard Post Office, Nelson Howard 257 Fleming, W. T. A. Waller Street, Murchison Murchison 183 Gibson, B. R. P.O. Box 184, Nelson Rai Valley 291 Gordon,· R. K. P.O. Box 34, Murchison Shenandoah 274 Granger Bros. -

Motueka River 1

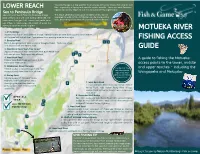

Towards the sea is a top spot for flinging lures to hungry trout which dine on bait LOWER REACH fish - especially in Spring and over the winter months. There are some fantastic ripples and willow edges to suit the consummate fly anglers also. Sea to Peninsula Bridge Open all year round (from the Peninsula Bridge This reach generally holds good numbers of fish, but be downstream), and with bait fishing permitted, the prepared to walk as fish distribution can be more patchy lower reach has got it all. From clear pools, runs here, depending on the time of year and river conditions. and riffles, to tidal water, this stretch of water has plenty of variation for all anglers. MOTUEKA RIVER 1. SH 60 Bridge Access available on both sides of bridge. Vehicle access on west bank up and down stream on the true left side of river. Foot access from parking area on true right. FISHING ACCESS 2. Douglas Road 1 Park at designated car park at end of Douglas Road. Walk over style 1 and follow track markers to river. GUIDE 3. West Bank Road “Gum Tree Corner” Approximately 5km from SH 60 off West Bank Road true 3 left side of river. Parking on side of road. 4 2 4. West Bank Road A guide to fishing the Motueka: Follow West Bank Road upstream 0.3km from Gum Tree Corner. 5 access points to the lower, middle 5. Whakarewa Street Motueka Vehicle access to road end gate with foot 'True right' or 'true and upper reaches - including the left' refers to the access up and down true right of river. -

N:Rnw ZEALAND' Gazei't~ 1431 "

, ~ov. 25] ,THE 'N:rnW ZEALAND' GAZEi'T~ 1431 " Reg. Location ~f Mill.; No. Opera.tor. Postal. Address. NELSON CONSERVANOY 26 Abbott and Christian Motupipi R.M.D., Takaka Motupipi. 166 Alborn, V. W. 190 Lincoln Road, Addington" Christchurch Cronadun. 16 Anderson, F. L., Ltd. P.O. Box 36, Murchison Lyell. 188 Andrews,. C. H. Motupipi Road, Takaka Takaka. I Anglesey, ~. W. Tadmor, Nelson Tadmor. 154 Aorere Timber Co., Ltd. Rockville Upper Aorere. 176 Badcock, J.J. Murchison Matiri. ll3 Baigent, A. T. -268 Rutherford Street, Nelson Wairoa Gorge. 5 .Baigent, H., and Sons, Ltd. P.O. Box 97, Nelson Kainui. 6' BaigeIit, H., and S01;1S, Ltd. P.O. Box 97, Nelson Tasman.' 7 Baigent, H., and Sons, Ltd. P.O. Box 97, Nelson Belgrove. 38 Baigent, H., and Son.s, Ltd. P.O. Box 97, Nelson Mildura. 61 Baigent, R., and Sons, Ltd. P.O. Box 97, Nelson Redwoods Valley. 103 Baigent, H~, and Sons, Ltd. P.O. Box 97, Nelson Berlins. ll5 Baigent, R., and Sons, Ltd. P.O. Box 97, Nelson Motueka. ll6 Baigent, H., aio,d Sons, Ltd. P.O. Box 97, Nelson Waiwhero. 131 Baigent, H.~.and Sons, Ltd. P.O. Box 97, Nelson Tinline. 132" Baigent, .H., and Sons, Ltd. P.O. Box 97, Nelson Waimea West. 133 Baigent, H., and Sons, Ltd. P.O. Box 97, Nelson Wakefield. 155 Bastin, W., and Sons .. · Wakefield Howard.. ll2 Benara TlmberCo., Ltd. P.O. Box 10; Nelson Mangatakau. 160 Blackwater MInes, Ltd. P.O. Box 41, Reefton Snowy River. 152 Brown's Creek Sawmill Ikamatua Ikamatua. -

NZ Nelson Great Taste Trail SG Cycle

THE GREAT TASTE CYCLE TRAIL & ABEL TASMAN NATIONAL PARK 5-day / 4-night easy – moderate GUIDED inn-to-inn cycling from & back to Nelson E-BIKE TOUR The Great Taste Trail Coastal Route starts in Nelson and ends at Kaiteriteri, gateway to Abel Tasman National Park and this tour samples both. This region is renowned for stunning coastal scenery, rural landscapes, artistic communities and some of the many great tastes New Zealand has to offer. Cycling through regional townships, past sparkling coastlines, rivers and hill valleys, orchards, vineyards, breweries and cafes, along the signposted paved and gravel trail. Indulge in the incredible diversity as you sample along the trail that is well serviced with excellent cafes, award winning wineries and craft breweries. Seifried Estates and McCashins Brewery are not to be missed. Enjoy local wine, seasonal fruit and berries, fresh seafood and cheeses on the ride. Take one day off your bike and cruise into the Abel Tasman National Park with a Day Pass, a picnic lunch and time to cruise, relax on a golden beach, walk and swim in the park. By pre-arrangement you could add sea kayaking (at extra cost). There are so many ways to enjoy a day in the park and this tour offers a unique opportunity to do so. Each morning your experienced cycle guide will provide a briefing on the day ahead. You are then free to ride at your own pace and meet the group at day’s end. Your guide and support vehicle will be in the area during the day, should you need assistance. -

Motueka River Access Points 1

Fish & Game NZ PROTECT OUR WATERS Access Help stop the spread of didymo, an aquatic alga pest. Fish and Game Access Points CHECK Remove all obvious clumps from all items and associated signs have been that have been in contact with the water and look for provided at various locations hidden clumps when leaving waterways. Leave the along the Motueka River and clumps at the waterway. many tributaries. In most of these locations you are free to access the river without having to ask permission, CLEAN Soak or scrub all items for at least one however in some locations you need to ask permission minute with any of the following: first (check the description details on the map). • Hot (60ºC) water Please respect private property and abide by the Access • 2% solution of household bleach Rules below to ensure the continued use of these areas. • 5% solution of salt • 5% solution of nappy cleaner Photo: Zane Mirfin Access Rules • 5% solution of antiseptic hand cleaner (6-10+ lb) present throughout the system, although Please ensure your behaviour doesn’t jeopardise the • 5% solution of dishwashing detergent average fish size is approx 2-3lb. Despite high numbers goodwill of landowners by following the simple rules A 2% solution is 200ml, a 5% solution is 500ml of trout, distribution can be patchy and fish difficult to below. (two large cups) with water to make 10 litres. catch at times. • Park vehicles away from tracks and gates. DRY If cleaning is not practical (eg: animals) dry • Do not litter. Early in the season, trout are often quite deep and the item to the touch and then leave for at least • Leave gates as you find them. -

Great Taste Trail — NZ Walking Access Commission Ara Hīkoi Aotearoa

9/30/2021 Great Taste Trail — NZ Walking Access Commission Ara Hīkoi Aotearoa Great Taste Trail Cycling Mountain Biking Difculties Easy , Medium Length 172.9 km Journey Time 3-4 days Regions Tasman , Nelson Sub-Regions Tasman , Nelson Part of the Collection Nga Haerenga - The New Zealand Cycle Trail https://www.walkingaccess.govt.nz/track/great-taste-trail/pdfPreview 1/4 9/30/2021 Great Taste Trail — NZ Walking Access Commission Ara Hīkoi Aotearoa A fantastic combination of iconic attractions like the Abel Tasman National Park, the nearby Golden Bay region, year-round mild temperatures, award-winning wineries, breweries and cafes and strengths in the arts, the Nelson-Tasman region is a wonderful place for any person to explore - and it's even better on a bike. Tasman's Great Taste Trail will appeal to a variety of cyclists; everyone from cross country riders taking on the whole loop, to casual day-trippers around the coast. This fantastic 4 day, 175 km ride will take in the absolute best of the Nelson Region and cater to all levels of cyclists. The majority of the route is Grade 1 and 2, catering for all abilities. Some of the inland route is Grade 3 riding, still suitable for most riders. As of 2018, most of the route is now complete, with only the inland section between Norris Gully and Riwaka still utilising the rural road network. There are numerous itineraries for this route, so choose your own. The itinerary below suggests an easy two-day cruise along the coast, with two longer, more challenging days on the inland route. -

Geology of the Nelson Area

GEOLOGY OF THE NELSON AREA M.S. RATTENBURY R.A. COOPER M.R.JOHNSTON (COM PI LERS) ....., ,..., - - .. M' • - -- Ii - -- M - - $ I e .. • • • ~ - - 1 ,.... ! • .- - - - f - - • I .. B - - - - • 'M • - I- - -- -n J ~ :; - - - " - , - " • ~ I • " - - -- ...- •" - -- ,u h ... " - ... ," I ~ - II I • ... " -~ k ". -- ,- • j " • • - - ~ I• .. u -- .. .... I. - ! - ,. I'" 3ii:: - I_ M wiI ~ .0 ~ - ~ • ~ ~ •• I ---, - - .. 0 - • • 1~!1 - , - eo - - ~ J - M - I - .... • - .. -~ -- • ,- - .. - M , • • I .. - eo -- ~ .1 - ~ - ui J -~ ~ •• , - i - - ~ • c--,- 1.10 ___ - ) ~ - .... - ~ - - 1 - -- ~ - '" - ~ ~ .. •• ~ - M - I Ito--...., •• ..-. - II - - - M ~ - I - • - 11, - • • ,- ~ - - ,e - ~ , • - ~ __- [iij.... i _ ... • ~ ~ - - ~ • "-' .. -- h ~ 1 I ~ ~ - - ~ - - • Interim New Zealand ,- 0.- ~ ~ , M ~ - geological time scale from ~ - Crampton & others (1995), " .... - ~ "I ~ •• , I - with geochronology after - , Gradslein & O9g (1996) - -- and Imbrie & others (1984). GEOLOGY OF THE NELSON AREA Scale 1:250 000 M.S. RATTENBURY R.A. COOPER M.R. J OHNSTON (COMPILERS) Institute of Geologica l & N uclear Sciences 1:250000 geological map 9 Institute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences Limited Lower Hutt, New Zealand 1998 BIB LIOG RAPHIC REFEREN CE Ra ttcnbury, M.S., Cooper. R,A .• Johnston. M.R. (co mpilers) 1998. Geology of the Nelson area. Ins titute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences 1:250000 geological map 9. 1sheet + 67 p. Lower HUll, New Zealand : Instit ute ofOeological & Nuclear Sciences Li mited. Includes mapping, compilation, and a contribution to -

ICM Technical Report

The Motueka and Riwaka catchments : a technical report summarising the present state of knowledge of the catchments, management issues and research needs for integrated catchment management / compiled by L.R. Basher. -- Lincoln, Canterbury, N.Z. : Landcare Research New Zealand, 2003. ISBN 0-478-09351-9 1. Water resources development New Zealand Motueka River Watershed. 2. Water resources development New Zealand Riwaka River Watershed. 3. Motueka River Watershed (N.Z.) 4. Riwaka River Watershed (N.Z.) I. Basher, L. R. UDC 556.51(931.312.3):556.18 The Motueka and Riwaka catchments A technical report summarising the present state of knowledge of the catchments, management issues and research needs for integrated catchment management Compiled by L.R. Basher1 Contributors J.R.F. Barringer1, W.B. Bowden2, T. Davie1, N.A. Deans3, M. Doyle4, A.D. Fenemor5, P. Gaze6, M. Gibbs7, P. Gillespie7, G. Harmsworth8, L. Mackenzie7, S. Markham4, S. Moore6, C. J. Phillips1, M. Rutledge6, R. Smith4, J.T. Thomas4, E. Verstappen4, S. Wynne-Jones6, R. Young7 1 Landcare Research, Lincoln 2 Formerly Landcare Research, Lincoln; now University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont, USA 3 Nelson Marlborough Region, Fish & Game New Zealand, Richmond 4 Tasman District Council, Richmond 5 Landcare Research, Nelson 6 Department of Conservation, Nelson 7 Cawthron Institute, Nelson 8 Landcare Research, Palmerston North May 2003 Preface When beginning any new research to managing our land, rivers and coast in an programme, a key first step is to understand interconnected holistic fashion. ICM encompasses existing knowledge about the topic. This report the principles of integration among science is the synthesis of existing knowledge about the disciplines, integration between communities, environment of the Motueka River catchment. -

Tasman District LANDSCAPE STUDY 2021

Tasman District LANDSCAPE STUDY 2021 OUTSTANDING NATURAL FEATURES AND LANDSCAPES DRAFT for Landowner Consultation Prepared for: Tasman District Council bridgetgilbert March 2021 | Status: DRAFT landscapearchitecture [INSERT PROJECT TEAM LOGOS HERE] 2 3 Y Y D D U U ST ST E E E CAP CAP S S D D N N A A L Contents L CT CT I I TR Front material to be inserted TR Section A: Executive Summary ���������������������������������������������������������5 N DIS N Copyright information DIS N A Acknowledgements A SM SM A Short description of document for referencing purposes Section B: Introduction to the Tasman District Landscape Study �������9 A T T Background 10 Project Team: Tasman District Council Landscape Assessment ‘Principles’ 13 Bridget Gilbert Landscape Characterisation 14 Dr Bruce Hayward Landscape Evaluation 17 Davidson Environmental Limited Mike Harding Is it a ‘Landscape’ or ‘Feature’? 18 Boffa Miskell Limited Threshold For ‘Natural’ 20 Threshold For ‘Outstanding’ 21 Expert Geoscience Input 22 Expert Ecology Input 23 Cultural Values and Iwi Consultation 23 Shared and Recognised Values 24 GIS Data Sources and Mapping 26 ONFs 26 ONL and ONF Mapping 28 DRAFT FOR LANDOWNER CONSULTATION LANDOWNER FOR DRAFT CONSULTATION LANDOWNER FOR DRAFT ONL and ONF Schedules 30 Section C: Tasman District Landscape Study Methodology �������������33 Assumptions 36 Section D: Outstanding Natural Landscapes ����������������������������������39 Contents: Outstanding Natural Landscapes 40 Section E: Outstanding Natural Features ����������������������������������������89