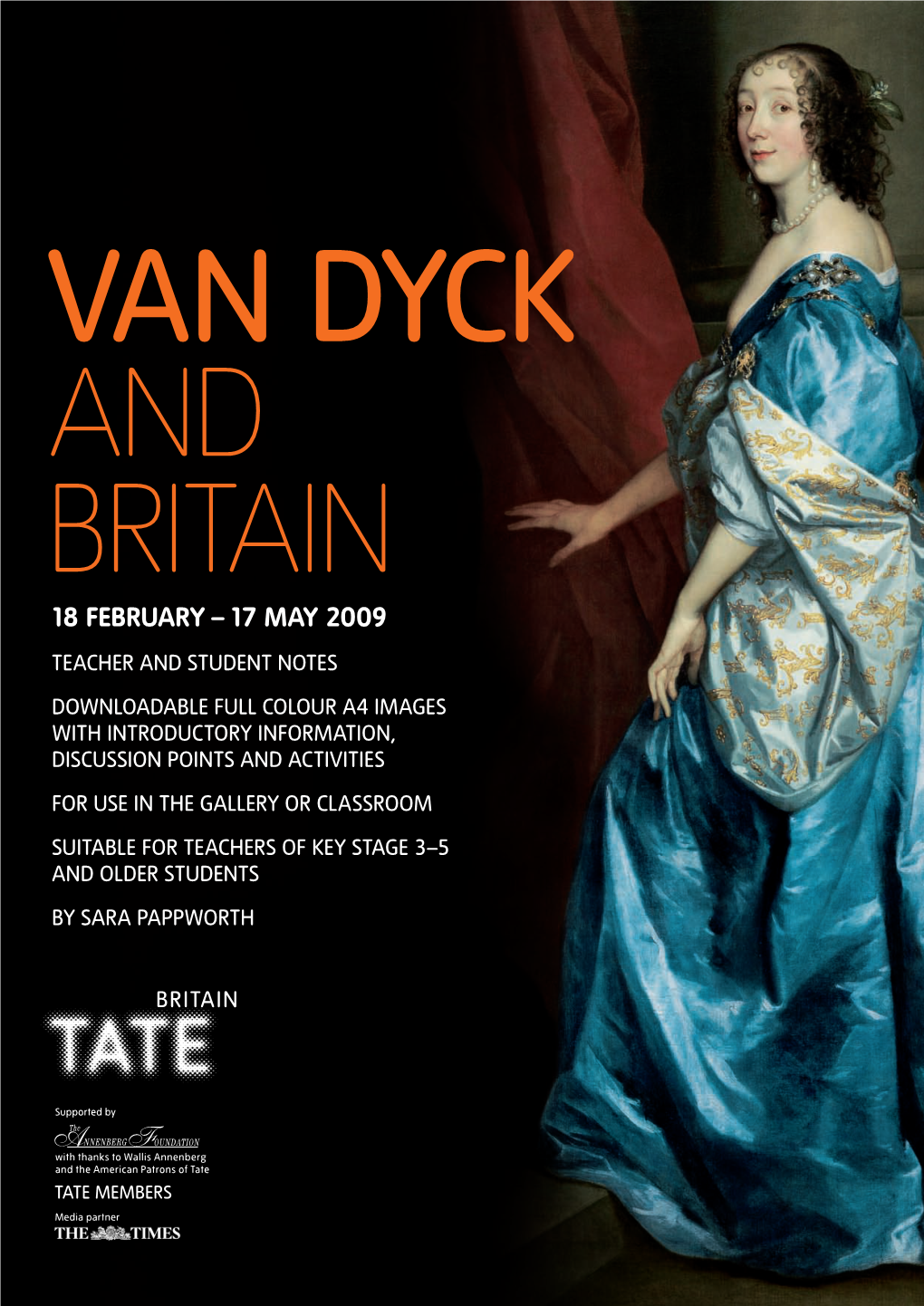

Van Dyck and Britain Teachers' Pack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twilight Payment Captures Melbourne Cup As Mcneil Sparkles | 2 | Wednesday, November 4, 2020

STEVE MORAN WE MOVED HEAVEN AND EARTH TO HAVE INTERNATIONAL CUP RUNNERS - AND NOW WE ARE PAYING THE PRICE - PAGE 17 Wednesday, November 4, 2020 | Dedicated to the Australasian bloodstock industry - subscribe for free: Click here Twilight Payment (right) RACING PHOTOS What's on Twilight Payment Metropolitan meetings: Launceston (TAS) Race meetings: Grafton (NSW), Kyneton (VIC), Kilcoy (QLD), Port Lincoln (SA), captures Melbourne Avondale (NZ) Barrier trials / Jump-outs: Warwick Farm (NSW), Grafton (NSW), Mornington (VIC), Cup as McNeil sparkles Mortlake (VIC), Toowoomba (QLD), Port Second O’Brien father-son quinella marred by fatal injury to Lincoln (SA) Derby winner as McEvoy cops record whip fine International meetings: Sha Tin (HK), Lingfield (UK), Nottingham (UK), Kempton But the event was marred by a fatal fetlock BY ANDREW HAWKINS | @ANZ_NEWS (UK), Dundalk (IRE), Greyville (SAF) injury to last year’s Epsom Derby (Gr 1, 1m oseph O’Brien led home his father Aidan 4f) winner Anthony Van Dyck (Galileo), the in the Melbourne Cup (Gr 1, 3200m) for Cup’s fifth racing-related injury resulting in the second time in four years yesterday death since 2013, while Kerrin McEvoy, aboard as Twilight Payment (Teofilo) held off runner-up Tiger Moth, received an Australian JTiger Moth (Galileo) under a sensational record whip fine of $50,000 and a 13-meeting Jye McNeil ride, giving owner Lloyd Williams a suspension as Racing Victoria stewards made historic seventh success in the race that stops good on their threat to heavily penalise overuse the nation at Flemington. of the crop. Continued on page 2>> Follow us @anz_news | 1 | Brought to you by Twilight Payment captures Melbourne Cup as McNeil sparkles | 2 | Wednesday, November 4, 2020 << Continued from page 1 The news overshadowed what will Plaudits for McNeil at first Cup ride be remembered as one of the toughest Melbourne Cup wins the contest has seen in its 160-year history, with McNeil’s ride sure to go down in the annals of history as an all-time great performance. -

190114 Tefaf Museum Restoration Fund Supports the Conservation and Restoration of Important Works at National Gallery and Museum

TEFAF MUSEUM RESTORATION FUND SUPPORTS THE CONSERVATION AND RESTORATION OF IMPORTANT WORKS AT NATIONAL GALLERY, UK AND MUSEUM VOLKENKUNDE, THE NETHERLANDS The Executive Committee of The European Fine Art Foundation (TEFAF) has awarded a total of €50,000 from TEFAF’s Museum Restoration Fund to support the distinct and complex restoration and conservation projects at the National Gallery, UK, and the Museum Volkenkunde, The Netherlands, for the benefit of future generations. At the National Gallery, the fund will support the restoration of the famous work ‘The Equestrian Portrait of Charles I’ by Anthony van Dyck (1599 – 1641), a powerful painting of the King, whilst at the Museum Volkenkunde, it supports a previously unknown and entirely unique 8-fold screen by Japanese artist Kawahara Keiga (1786 – c.1860), ‘View of Deshima in Nagasaki Bay’. Founded in 2012, the TEFAF Museum Restoration Fund supports the restoration and conservation of culturally significant works within museums and institutions worldwide. Museums and institutions that have attended TEFAF Maastricht are eligible to apply for the grants, which are awarded by an independent panel of experts. Supporting the wider art community is an integral part of TEFAF’s DNA and the Fund is one way the Foundation demonstrates its ongoing dedication to cultural heritage. Presentations about each project will be displayed at TEFAF Maastricht, the world’s leading fine art and antiques Fair, which takes place from the 16-24 March 2019 at the MECC (Maastricht Exhibition and Congress Centre), Maastricht, The Netherlands. The National Gallery, UK The National Gallery houses one of the world’s finest collections of paintings, attracting between 5 and 6 million visitors every year, who are taken on a journey through European art over seven centuries, from the 13th century to the early 20th century. -

Oti Racing 29

OMCATROCBHE R2 2 9 2T0H2 02020 ISSVUOEL 2 091 1 OTI GAZETTE The official newsletter of OTI RACING and Management Aidan O’Brien’s Reputation Goes to a New Level IN THIS WEEK'S Aidan O’Brien and his sons’ reputations as trainers went to a new level last EDITION weekend when they decided to withdraw their horses from feature European races, along with Roger Varian. Not surprisingly, some of their peers who were also supplied by the feed merchants at the centre of this Upcoming OTI Runners OTI Fun and Games OTI NEWS controversy, decided otherwise! A CONVERSATION Given the apparent clearance of the infected product in Ireland, O’Brien WITH could well have “ran the gauntlet” in the hope that any trace of Zilpaterol DEANE LESTER would have left the horses’ systems by race time. He chose instead to scratch and hence protect himself, his horses and indeed the industry from possible negative consequences. JOHN BERRY Aidan O’Brien is a tall poppy, a natural target for some of his competitors GET TO KNOW YOUR and those who thrive on innuendo. Unfortunately for them, the reality is FELLOW OTI OWNERS that he is a training genius. As competitive as he is, we also now know that - TRACEY CHAPMAN he is not a ‘win at all costs’ merchant. Through his actions last weekend that potentially cost some horses a stallion career, he displayed a level of integrity that many of us would like to see throughout racing. FUN & GAMES In the meantime, those who ‘ran the gauntlet’ in the hope that their horses DICK WHITTINGTON will produce clear swabs, will endure a few sleepless nights waiting for results. -

Safavid Figural Silks and the Display of Identity

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2008 Donning the Cloak: Safavid Figural Silks and the Display of Identity Nazanin Hedayat Shenasa De Anza College, [email protected] Nazanin Hedayat Munroe Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Shenasa, Nazanin Hedayat and Munroe, Nazanin Hedayat, "Donning the Cloak: Safavid Figural Silks and the Display of Identity" (2008). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 133. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/133 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Donning the Cloak: Safavid Figural Silks and the Display of Identity Nazanin Hedayat Shenasa [email protected] Introduction In a red world bathed in shimmering gold light, a man sits with his head in his hand as wild beasts encircle him. He is emaciated, has unkempt hair, and wears only a waistcloth—but he has a dreamy smile on his face. Nearby, a camel bears a palanquin carrying a stately woman, her head tipped to one side, arm outstretched from the window of her traveling abode toward her lover. Beneath her, the signature “Work of Ghiyath” is woven in Kufic script inside an eight- 1 pointed star on the palanquin (Fig. 1). Figure 1. Silk lampas fragment depicting Layla and Majnun. -

The Beginning of a Masterpiece? Cont

FRIDAY, 27 JULY 2018 KEW OUT, CRACKSMAN IN KING GEORGE THE BEGINNING OF In a surprise twist to the tale of Saturday=s G1 King George VI A MASTERPIECE? and Queen Elizabeth S. at Ascot, Aidan O=Brien ruled out the G1 Grand Prix de Paris winner Kew Gardens (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) after he scoped dirty before Thursday=s confirmation stage. Ballydoyle are supervising the wellbeing of the string due to the disappointing effort of Magic Wand (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) in Saturday=s G1 Irish Oaks, after which she was found to have had a dirty nose. AOur horses are just going through a little bit of a stage--a little bit of a change--and the odd one is not scoping right at the moment,@ he explained. AWe=ve seen it with the filly in the Oaks and we just have to be careful.@ The removal of Kew Gardens means that Ryan Moore is on last year=s G1 Qipco British Champions Fillies & Mares S. heroine Hydrangea (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) and the sole 3-year-old in the line-up will be the stable=s G1 Irish Derby runner-up Rostropovich (Ire) (Frankel {GB}). Cont. p5 Galileo=s Anthony Van Dyck takes the Tyros S. | Racing Post IN TDN AMERICA TODAY Despite having to navigate troubled waters as a bug infects PHOENIX ‘DREAMING’ BIG AT THE SPA parts of the Ballydoyle armada, Anthony Van Dyck (Ire) (Galileo Phoenix Thoroughbreds, off to a flyer at Saratoga with an {Ire}) was a faithful steer for Ryan Moore as he handed Aidan opening day ‘TDN Rising Star’, is primed for a big summer at the O=Brien a 12th win in resounding fashion in the G3 Japan Racing upstate oval. -

Mauri Delcher Intenta La Cima Con Pedro Cara

INTERNACIONAL PREVIA CRÍA Godolphin paga 210.000 euros A contrareloj: 3 días para que la Odriozola se hace con el precio por el hijo de Friné pista se seque Top de la subasta de la ACPSIE Página 2 Página 4 Página 7 www.blacktypemagazine.com | Jueves 24 de octubre de 2019 | Número 27 Mauri Delcher intenta la cima con Pedro Cara Pedro Cara viene de ser segundo en el Jockey Club Derby, en Nueva York NYRA La edición de 2019 del Royal-Oak (G1) se presenta espe- cuestión de balanceo, parecía cialmente interesante para los aficionados españoles. El que su temporada había llegado Iñigo Zabaleta Sr. Delcher decide dar el paso y presentará a esa realidad a su fin y que el año que viene @Porunpeloturf llamada Pedro Cara (Pedro The Great) frente a buena se presentaba como el del ascenso a la cima de las carreras parte de la élite europea sobre la larga distancia. Y si algo para stayers, pero si el Sr. Delcher da el paso de intentarlo tenemos que reconocerle al preparador español es que de es porque el caballo lo vale. Después, será la pista la que todo esto sabe, y mucho. Tras los éxitos, en distancias de decida la posición de cada uno, pero pase lo que pase a aliento, conseguidos con caballos como Bannaby (Dyhim Pedro Cara le queda por delante todo el futuro del mun- Diamond) o Domeside (Domedriver) todo apunta a que do. Pedro Cara puede tomar el relevo. Tal vez no sea ahora, a muy corto plazo, pero este tres años tiene a su favor, Como decíamos, la carrera esta lejos de ser poco competi- sin intervención de lesiones, el tiempo. -

2020 Rwitc, Ltd. Annual Auction Sale of Two Year Old

2020 R.W.I.T.C., LTD. ANNUAL AUCTION SALE OF TWO YEAR OLD BLOODSTOCK 142 LOTS ROYAL WESTERN INDIA TURF CLUB, LTD. Mahalakshmi Race Course 6 Arjun Marg MUMBAI - 400 034 PUNE - 411 001 2020 TWO YEAR OLDS TO BE SOLD BY AUCTION BY ROYAL WESTERN INDIA TURF CLUB, LTD. IN THE Race Course, Mahalakshmi, Mumbai - 400 034 ON MONDAY, Commencing at 4.00 p.m. FEBRUARY, 03RD (LOT NUMBERS 1 TO 71) AND TUESDAY, Commencing at 4.00 p.m. FEBRUARY, 04TH (LOT NUMBERS 72 TO 142) Published by: N.H.S. Mani Secretary & CEO, Royal Western India Turf Club, Ltd. Registered Office: Race Course, Mahalakshmi, Mumbai - 400 034. Printed at: MUDRA 383, Narayan Peth, Pune - 411 030. IMPORTANT NOTICES ALLOTMENT OF RACING STABLES Acceptance of an entry for the Sale does not automatically entitle the Vendor/Owner of a 2-Year-Old for racing stable accommodation in Western India. Racing stable accommodation in Western India will be allotted as per the norms being formulated by the Stewards of the Club and will be at their sole discretion. THIS CLAUSE OVERRIDES ANY OTHER RELEVANT CLAUSE. For application of Ownership under the Royal Western India Turf Club Limited, Rules of Racing. For further details please contact Stipendiary Steward at [email protected] BUYERS BEWARE All prospective buyers, who intend purchasing any of the lots rolling, are requested to kindly note:- 1. All Sale Forms are to be lodged with a Turf Authority only since all foals born in 2018 are under jurisdiction of Turf Authorities with effect from 1 Jan 2020. -

Portraits, Pastels, Prints: Whistler in the Frick Collection

SELECTED PRESS IMAGES Van Dyck: The Anatomy of Portraiture March 2 through June 5, 2016 The Frick Collection, New York PRESS IMAGE LIST Digital images are available for publicity purposes; please contact the Press Office at 212.547.0710 or [email protected]. 1. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Queen Henrietta Maria with Jeffery Hudson, 1633 Oil on canvas National Gallery of Art, Washington; Samuel H. Kress Collection 2. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) The Princesses Elizabeth and Anne, Daughters of Charles I, 1637 Oil on canvas Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh; purchased with the aid of the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Scottish Office and the Art Fund 1996 3. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Mary, Lady van Dyck, née Ruthven, ca. 1640 Oil on canvas Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid 1 4. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Charles I and Henrietta Maria Holding a Laurel Wreath, 1632 Oil on canvas Archiepiscopal Castle and Gardens, Kroměříž 5. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Prince William of Orange and Mary, Princess Royal, 1641 Oil on canvas Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam 6. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Pomponne II de Bellièvre, ca. 1637–40 Oil on canvas Seattle Art Museum 2 7. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Margaret Lemon, ca. 1638 Oil on canvas Private collection, New York 8. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Self-Portrait, ca. 1620–21 Oil on canvas The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Jules Bache Collection, 1949 9. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Frans Snyders, ca. 1620 Oil on canvas The Frick Collection; Henry Clay Frick Bequest Photo: Michael Bodycomb 3 10. -

The Antiques Roadshow to Be Sold at Christie’S London on 8 July, 2014

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Friday, 30 May 2014 VAN DYCK HEAD STUDY RECENTLY REDISCOVERED ON THE ANTIQUES ROADSHOW TO BE SOLD AT CHRISTIE’S LONDON ON 8 JULY, 2014 London – Christie’s is pleased to announce that a striking head study by Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), which was recently re-discovered on the BBC television progamme The Antiques Roadshow, will be offered at Christie’s Old Master & British Paintings Evening Sale, on Tuesday 8 July (estimate: £300,000-500,000, illustrated above). This work is a preparatory sketch for van Dyck’s full-length group portrait of The Magistrates of Brussels, which was painted in Brussels in 1634-35, when the artist was at the height of his powers. The painting was bought 12 years ago by Father Jamie MacLeod from an antiques shop in Cheshire for just £400. The proceeds of the sale will go towards the acquisition of new church bells for Whaley Hall Ecumenical Retreat House in Derbyshire to commemorate the centenary of the end of the First World War. This work will be exhibited for the first time ahead of the sale when it goes on free public view at Christie’s New York on 31 May to 3 June; it will also be on view in London ahead of the sale, on 5 to 8 July. The sketch was largely obscured by later over-paint and, as a result, had been overlooked by van Dyck scholars. Recent cleaning and restoration of the picture has revealed a swiftly executed head study entirely consistent with three other known sketches for the Magistrates of Brussels picture, a work that hung in the Brussels Town Hall until it was destroyed during the French bombardment of the city in 1695. -

The Substrates for British Colonization to Enter Iran in the Safavid Era Dr

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 3, Issue 6, June-2012 1 ISSN 2229-5518 The Substrates for British Colonization to Enter Iran in the Safavid Era Dr. Masoud Moradi, Reza Vasegh Abbasi, Amir Shiranzaie Ghale-No Abstract— Since the beginning of the sixteenth century AD and after the fall of Constantinople, the context was provided for dominating the countries like Spain, Portugal, France and England on seas and travelling to eastern countries. This domination coincided with the reign of the Tudors in England. One hundred and fifty years after Klavikhou and the rise of Antony English Jenkinson which was thought for making a trading relationship with Iran, many attempts have been made from the European communities to communicate with the Orient, including Iran which their incentive was first to make the movements of tourists easier and Christian missionaries and then to make the commercial routes more secure. Antony Jenkins was among the first who traveled to Iran in 1561 to establish commercial relations and then went to King Tahmasb. Thomas Alkak, Arthur Edwards and Shirley Brothers was among those who continued his way after him which Shirley Brothers was the most successful of them. This study aims to study, in a laboratory method, the beginning of Iran’s relation with England in the era of Tahmasb the first and its continuity in the era of King Abbas The First and how English colonization to enter Iran are established. Index Terms— Iran, England, Safavid, British tradesmen, commercial relations. —————————— —————————— 1 INTRODUCTION NTONY Jenkinson, the Initiator of British Activities sending the mission to Iran represented by Jenkins: first A in Iran: After the collapse of the Byzantine State to take aside the silk trade from the Portuguese being the (1453), European initiated their activities to reach most important commercial trade of Iran and then take Asia, especially the thriving market of India and exploit- over the exports by itself. -

Libeling Painting: Exploring the Gap Between Text and Image in the Critical Discourse on George Villiers, the First Duke of Buckingham

Libeling Painting: Exploring the Gap between Text and Image in the Critical Discourse on George Villiers, the First Duke of Buckingham THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ivana May Rosenblatt Graduate Program in History of Art The Ohio State University 2009 Master's Examination Committee: Barbara Haeger, Advisor Christian Kleinbub Copyright by Ivana May Rosenblatt 2009 Abstract This paper investigates the imagery of George Villiers, the first Duke of Buckingham, by reinserting it into the visual and material culture of the Stuart court and by considering the role that medium and style played in its interpretation. Recent scholarship on Buckingham‘s imagery has highlighted the oppositional figures in both Rubens‘ and Honthorst‘s allegorical paintings of the Duke, and, picking up on the existence of ―Felton Commended,‖ a libel which references these allegories in relation to illusion, argued dually that Buckingham‘s imagery is generally defensive, a result of his unstable position as royal favorite, and that these paintings consciously presented images of the Duke which explicitly and topically responded to verse libels criticizing him. However, in so doing, this scholarship ignores the gap between written libels and pictorial images and creates a direct dialogue between two media that did not speak directly to each other. In this thesis I strive to rectify these errors by examining a range of pictorial images of Buckingham, considering the different audiences of painting and verse libel and addressing the seventeenth-century understanding of the medium of painting, which defended painterly illusionism and positioned painting as a ritualized language. -

Universi^ Micn^Lms

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting througli an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete.