The CRTC's Enforcement of Canada's Broadcasting Legislation: ''Concern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THURSDAY—( Cont'd)

B— Lowell Thomas, See Monday KFBK KFH KFPY KFRC KGB KHJ THURSDAY—( Cont'd) KLRA KLZ KMBC KMJ KMOX ED-10:30 p.m., E-9:30, C-8:30, M-7:30 ED-7:00 p.m., E-6:00, C-5:00, M-4: 0 KOIN KOL KOMA KRLD KSCJ KSL C — Doris Lorraine; Cadets C — Myrt and Marge,See Monday KTRH KTSA KVI KWG WABC KLRA KMOX KOMA KTSA WABC B— Amos'n' Andy,See Monday WADC WBBM WBRC WBT WCAO WBRC WBT WCAO WGST WHAS ED-7:15 p.m., E-6:15, C-5:15, M-4:15 WCAU WCCO WDOD WDRC WDSU WKRC WLAC WMBR WREC WRR C — Just Plain Bill, See Monday WEAN WFBL WFBM WGST WHAS B — Archer Gibson, Organist B — Billy Bachelor,See Monday WHK WIBW WICC WJAS WJSV KDKA ESO KWCR KYW WBAL WBZ WKBW WKRC WLAC WMBG WMT WBZA WCKY WGAR WHAM WJZ ED-7:30 p.m., E-6:30, C-5:30, M-4:30 WNAC WOKO WOWO WREC WSPD WMAL WREN C— Music in Air,See Monday. WTAR WTOC B — George Gershwin, See Monday B — Armour Program; Phil Baker ED-10:45 p.m., E-9:45, C-8:45,M-7:45 ED-7:45 p.m., E-6:45, C-5:45 M-4:45 KDKA KDYL KFI KGO KGW KHQ C — Fray and Braggiotti B — Gus Van; Arlene Jackson KOA KOIL KOMO KPRC KSO KSTP CKLW WAAB WABO WADC WCAO KDKA WBAL WBZ WBZA WCKY KTAR KWK WAPI WBAL WBZ WDRC WFBL WFEA WGLC WHEC WBZA WEBC WENR WFAA WGAR WJAS WJSV WLAC WLBW WLBZ WENR WJZ WMAL WMC WSB WSM WHAM WIOD WJAX WJR WJZ WOKO WOWO WSPD WSMB WSYR WKY WMC WOAI WREN WRVA C — Myrt and Marge, See Monday C — Boake Carter, See Monday WSB WSM WSMB WTMJ WWNC R— Goldbergs, See Monday R — One Night Stand; Pick and Pat ED-11:00 p.m., E-10:00, C-9:00, M-8:00 ED-8:00 p.m., E-7:00, C-6:00, 11/1-5:00 KSD WBEN WCAE WCSH WDAF B — Amos 'n' Andy, See Monday C — Happy -

TOBY DAVID COLLECTION 1930’S – 1970’S Primarily 1935-1964

TOBY DAVID COLLECTION 1930’s – 1970’s Primarily 1935-1964 Accession Number: 2001.024 Size: 1 linear foot Number of Boxes: 2 archival boxes Box Numbers: BIO-5-D1 to BIO-5-D2 Object Numbers: 2001.024.029 to 2001.024.393 TOBY DAVID COLLECTION ACQUISITION: Donated to the Detroit Historical Museum by Gerald David in 2001. OWNERSHIP & COPYRIGHT: The Detroit Historical Society except where copyrights for publications, manuscripts, and photos remain in effect. ARRANGEMENT: Organized, researched, and cataloged with a finding aid prepared by Lauren Aquilina, Wayne State University practicum student, in January – April, 2019. ACCESS & USE: Opened to researchers and other interested individuals in 2019 without restriction except where physical condition or technology precludes use. BACKGROUND HISTORY of COLLECTION This collection contains mostly photographs as well as some papers and ephemera of Toby David during his career in radio and television spanning from 1935 to 1964. David was born in New Bern, North Carolina, on September 22, 1914, and moved to the Detroit area with his family in the mid-1920s. He attended Ford Trade School in Highland Park before getting a job at Chrysler where he performed in their amateur talent shows. His first radio job was at CKLW in Windsor, Ontario, on The Early Morning Frolic beginning in 1935. In 1940, David moved to Washington, D.C., with Larry Marino. Together, they were a comedy duo known as The Kibitzers. While in D.C. during World War II, David organized Treasury bond shows, entertained servicemen, and emceed President Roosevelt’s birthday celebrations three years in a row. -

ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM Fiscal Year Ended August 31, 2015 Corus

ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM Fiscal year ended August 31, 2015 Corus Entertainment Inc. November 9, 2015 ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM ‐ CORUS ENTERTAINMENT INC. Table of Contents FORWARD‐LOOKING STATEMENTS ........................................................................................................ 3 INCORPORATION OF CORUS .................................................................................................................. 4 Organization and Name ............................................................................................................................ 4 Subsidiaries ............................................................................................................................................... 5 GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUSINESS ........................................................................................... 5 Significant Acquisitions and Divestitures ................................................................................................. 5 DESCRIPTION OF THE BUSINESS ............................................................................................................. 6 Strategic Priorities .................................................................................................................................... 6 Radio ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Description of the Industry ............................................................................................................... -

New Solar Research Yukon's CKRW Is 50 Uganda

December 2019 Volume 65 No. 7 . New solar research . Yukon’s CKRW is 50 . Uganda: African monitor . Cape Greco goes silent . Radio art sells for $52m . Overseas Russian radio . Oban, Sheigra DXpeditions Hon. President* Bernard Brown, 130 Ashland Road West, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Notts. NG17 2HS Secretary* Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Treasurer* Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] MWN General Steve Whitt, Landsvale, High Catton, Yorkshire YO41 1EH Editor* 01759-373704 [email protected] (editorial & stop press news) Membership Paul Crankshaw, 3 North Neuk, Troon, Ayrshire KA10 6TT Secretary 01292-316008 [email protected] (all changes of name or address) MWN Despatch Peter Wells, 9 Hadlow Way, Lancing, Sussex BN15 9DE 01903 851517 [email protected] (printing/ despatch enquiries) Publisher VACANCY [email protected] (all orders for club publications & CDs) MWN Contributing Editors (* = MWC Officer; all addresses are UK unless indicated) DX Loggings Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] Mailbag Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Home Front John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB 01442-408567 [email protected] Eurolog John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB World News Ton Timmerman, H. Heijermanspln 10, 2024 JJ Haarlem, The Netherlands [email protected] Beacons/Utility Desk VACANCY [email protected] Central American Tore Larsson, Frejagatan 14A, SE-521 43 Falköping, Sweden Desk +-46-515-13702 fax: 00-46-515-723519 [email protected] S. -

Warning Phase Activities of the 1974 Windsor Tornado

DISASTER RESEARCN CEiaER TEE OEIQ STATE UNIVERSITY COLUPIBUS, OHIO 43203. Working Paper 60 THE WARNING PHASE ACTXVITIES OF THE 1974 WIIWSQR TORNADO fiodney id. Kueneman El40 Fellow Disaster Research Center The Ohio State University G. Alexander Ross Rese arch As soc i at e Disaster Research Center The Ohio State University 4/74 This material is not to be quoted or referenPr4 'I The Warngng Phase Activities of the 1974 Windsor Tornado On April 3, 1974, a tornado touched down briefly in Windsor, Ontario, destroy- ing a curling rink and killing 8 persons. The only other significant damage was sustained by an addition to a shopping mil. The purpose of thfs study is to chart the activities cf various relevant organ- izations with reepect to the warning phase of the tornado threat. In order to accom- plish this task it wLll be necessary to analyze the nature of the relationships between: 1) the IS. S. Weather Bureau and the Canadian Weather Bureau (both its Toronto and Wtndsor offices), 2) the Windsor Weather Bureau and the Local EMO, 3) Local EM0 and the media and various emergency relevant organizations and 4) the Canadian Weather Bureau, the U.S. Weather Bureau and the media. U.S. Weather Service-Canadian Weather Service Windsor, Ontario has a weather office staffed with weather technicians. Since it has no meteorologists on staff, it receives the weather bulletins, whish it re- leases from the weather office in Toronto, some 250 miles away. Toronto determines its weather forecasts for the Windsor-Essex County region in part from data it re- ceives from the Detroit Weather Office. -

Canadian Association of Broadcasters

January 11, 2019 The Broadcasting and Telecommunications Legislative Review Panel c/o Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada 235 Queen Street, 1st Floor Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0H5 [email protected] Dear Review Panel Members: Re: Call for Comments on the Questions set out in the Broadcasting and Telecommunications Legislative Review Panel Terms of Reference The Canadian Association of Broadcasters CEO Radio Council (CAB Radio Council or Council) is pleased to provide the enclosed written submission in response to the Review Panel’s Call for Comments on Canada’s Communications Legislative Framework. The CAB Radio Council is a special committee of the CAB whose primary purpose is to advocate on behalf of the private commercial radio industry on matters of national interest which affect radio’s competitiveness and ability to serve Canadians. The council is comprised of representatives from more than 500 AM and FM radio stations across Canada which comprise in aggregate over 95% of total radio industry revenues. The attached submission represents the consensus view of the CAB Radio Council in respect of legislative and policy matters raised by the questions relating to the Broadcasting Act and relevant to radio. We trust that our comments are of value to the Panel and would be pleased to provide any additional input should it be requested. As the CRTC is an important stakeholder in this process and our submission raises radio policy issues not dependent on legislative review, we are also providing a copy of our submission to the Secretary General. Yours truly, Ian Lurie Chair, CAB CEO Radio Council cc. -

Our Stories, Our Voice Campaign

Our Stories, Our Voice Campaign to create and share educational and entertaining Canadian content to a bi-national audience Canadians have important stories to tell about our own remarkable history, our first class cultural institutions, and who we are as a people. But who will support this storytelling, and how should it be disseminated? Bringing Canadian narratives to a broader audience is of utmost importance. A creative strategy is required to develop, inform, and promote what is distinctly Canadian not only to Canada but beyond geographic borders. The potential exists for CCPTA to promote richer, more meaningful content about the Canadian experience, as well as use its history of collaboration with Buffalo Toronto Public Media to distribute that content through affiliated NPR and PBS stations. Funding is needed to support the necessary research, development, and production costs that will make this content a reality. 1 You can help to give Canadians a voice! By creating and delivering uniquely Canadian content, we can more effectively educate the world about what it means to be Canadian. Through compelling partnerships with organizations such as Buffalo Toronto Public Media, CCPTA has valuable access to PBS, NPR and other educational television and radio outlets. Why partner with PBS and NPR affiliates to disseminate Canadian stories beyond our borders? 2 The Our Stories, Our Voice Campaign The Central Canadian Public Television Association (CCPTA), has launched the Our Stories, Our Voice $5 million dollar endowment campaign that will strengthen our educational objectives and expand our gateway for Canadian content producers. The annual income disbursed from the endowment will support the research and development of Canadian focused television productions as well as fund writers and producers to assist in bringing that content to a broad audience. -

Canadian Content in the Media C

9.1.5 Canadian Content in the Media c A cartoon that appeared in 1998 in the Regina Leader-Post during the free trade debate showed a sloppy, middle-aged Canadian wearing a Miami Vice T-shirt, walking down a street adorned with McDonald’s arches, Coke machines, GM and Ford dealerships, and a movie billboard advertising Rambo XI. “What’s really scary,” he says to his wife, “is that we Canadians could lose control of our culture.” From The Mass Media in Canada by Mary Vipond. Canadian content rules considered insufficient by Graham Fraser, Toronto Star, August 29, 2002 <www.friends.ca/News/Friends_News/archives/articles08290205.asp> A recent survey found Canadians are confident the country's culture and identity are stronger now than they were five years ago in terms of distinctiveness from the United States. However, they worry about the ability to control domestic affairs from U.S. pressure in the future. A strong majority believes in Canadian content requirements and do not consider them vigorous enough. They say the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation is important for maintaining and building culture and identity. This support for Canadian culture and the CBC emerged in a poll by Ipsos-Reid for Friends of Canadian Broadcasting that was conducted between Aug. 6 and 11, 2002. The poll questioned 1,100 Canadians, and it can be considered accurate within plus or minus 3 percent, 19 times out of 20, Chris Martyn of Ipsos-Reid said. When questioned about agreement with the statement "I am proud of Canadian culture and identity," 94 percent said they agreed, while 92 percent said Canadian culture and identity should be promoted more, and 89 percent agreed it was important that the Canadian government work to maintain and build a culture and identity distinct from the U.S. -

Canadian Content Regulations and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

CANADIAN JOURNAL OF COMMUNICATION, 1986, 11 (I),41 - 53. CANADIAN CONTENT REGULATIONS AND THE CANADIAN CHARTER OF RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS Brenda M. McPhail The University of Calgary This article examines the Canadian content regulations for television in the context of s. 2(b) of the Charter of Riahts and Freedoms. It araues that on the basis of s. 1, these regulations may be demonstrably justified. Cet article examine les reglements concernent le contenu canadien de la thlevision canadienne dans le contexte de la s. 2(b) de la Charte Canadienne des Droits et LibertBs. I1 demontre que les rhglements sont justifiable B la lumihre de la s. 1. On 17 April 1982 Queen Elizabeth I1 proclaimed the Constitution Act 1982 the supreme law of Canada. Its coming into force was heralded by many as the long-awaited and dramatic severance of the colonial mbi lical cord with Britain. Others, however, were more circumspect, for included in the act was the Canadian Charter of Rights and Free- doms. This novel element in Canada's constitution led to much specu- lation about its effects on Canadian jurisprudence and on the nation as a whole. This article investigates the possible implications of the Charter in one significant sphere of government regulatian . More specifically: do the Canadian television content regulations, as prescribed by the Canadian Radio-television and telecommunications Commission under the authority granted it by the Parliament of Canada in the Broadcasting Act 1968, violate s.2(b) of the Charter, the guarantee of freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, includ- ing freedom of the press and other media of comnunication? Second, if they do, can these regulations be justified by invok ing s The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject to only such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society. -

Content Everywhere (2): Securing Canada’S Place in the Digital Future

Content Everywhere (2): Securing Canada’s Place in the Digital Future White Paper by Duopoly February, 2015 1 1 Table of Contents – Content Everywhere 2 1. Content Everywhere 2: Securing Canada’s Place in the Digital Future Introduction: a. Scope of the White Paper b. 'Videofication' of the Internet Takes Hold c. The Great Unbundling d. Canada Follows Suit e. What’s Different? Note: This paper has been prepared with the input of many entertainment and 2. What are the Major Trends? media industry leaders, listed in Appendix B. The authors thank these a. The US Leads the Way individuals for their contribution to this study. b. OTTs Surging Buying Power c. More Players Jump Into the Digital-First Game Funding for this study was provided by Ontario Media Development d. Smaller Players Pioneer Original Content Corporation, the Canada Media Fund and the Independent Production e. Old Media Races to Catch Up Fund. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the 3. Preliminary Findings From Industry Reviews views of Ontario Media Development Corporation, Canada Media Fund, the Government of Ontario or the Government of Canada, or the Independent 4. Case Studies Production Fund. The funders, the Governments of Ontario and Canada and a. Canada: Annedroids; Out With Dad; Bite on Mondo; CBC ComedyCoup; their agencies are in no way bound by the recommendations contained in b. US: East Los High; Frankenstein MD; Marco Polo this document. c. UK: Ripper Street; Portal; The Crown Version disponible en français dans trends.cmf-fmc.ca/fr 5. -

VIZEUM CANADA INC. Suite 1205, Oceanic Plaza, 1066 West Hastings Vancouver BC V6E 3X1 (604) 646-7282

VIZEUM CANADA INC. Suite 1205, Oceanic Plaza, 1066 West Hastings Vancouver BC V6E 3X1 (604) 646-7282 NEWSPAPER CLIENT: Ministry of Finance PUBLICATION NET TOTAL BC DAILIES VANCOUVER - LOWER MAINLAND VANCOUVER SUN $138,495.90 VANCOUVER PROVINCE $71,257.50 NORTHERN BC DAWSON CREEK DAILY NEWS $10,002.00 FORT ST. JOHN ALASKA HWY NEWS $10,502.10 PRINCE GEORGE CITIZEN $14,473.70 THE ISLAND ALBERNI VALLEY TIMES $9,671.06 NANAIMO DAILY NEWS $12,195.40 VICTORIA TIMES COLONIST $53,158.10 THOMPSON OKANAGAN KAMLOOPS DAILY NEWS $17,269.10 KELOWNA DAILY COURIER $17,362.80 PENTICTON HERALD $15,403.70 KOOTENAY ROCKIES CRANBROOK DAILY TOWNSMAN $7,518.00 KIMBERLEY DAILY BULLETIN $6,489.60 TRAIL DAILY TIMES $9,905.70 NATIONAL DAILY GLOBE AND MAIL - BC EDITION $37,414.42 FREE DAILIES 24 HOURS $39,004.00 METRO VANCOUVER $33,690.00 Page 1 Page 1 of 9 FIN-2011-00084 VIZEUM CANADA INC. Suite 1205, Oceanic Plaza, 1066 West Hastings Vancouver BC V6E 3X1 (604) 646-7282 BC COMMUNITIES VANCOUVER - LOWER MAINLAND BURNABY NOW $13,102.80 BURNABY/ NEW WEST NEWS LEADER $20,374.20 COQ/PT COQ/PT MOODY TRI-CITY NEWS $17,331.30 COQUITLAM NOW $13,102.80 DELTA OPTIMIST $8,269.80 DELTA, SOUTH DELTA LEADER $4,709.60 LANGLEY ADVANCE $9,753.54 LANGLEY TIMES $14,685.30 MAPLE RIDGE / PITT MEADOWS NEWS $11,778.20 MAPLE RIDGE / PITT MEADOWS TIMES $8,919.90 NEW WESTMINSTER, THE RECORD $8,549.04 RICHMOND NEWS $14,515.20 RICHMOND REVIEW $15,019.20 SURREY / NORTH DELTA LEADER $22,491.00 SURREY NOW $18,505.80 VANCOUVER COURIER - ALL $45,090.00 VANCOUVER WESTENDER $10,399.90 WHITE ROCK PEACE ARCH NEWS $13,097.70 BUSINESS IN VANCOUVER $6,392.00 VANCOUVER - FRASER VALLEY ABBOTSFORD / MISSION TIMES $11,175.00 ABBOTSFORD NEWS (Abbotsford & Mission) $18,144.00 AGASSIZ-HARRISON OBSERVER $2,248.40 ALDERGROVE STAR $3,219.30 CHILLIWACK PROGRESS $14,778.40 CHILLIWACK TI MES $9,565.80 HOPE STANDARD $3,014.90 MISSION RECORD $4,036.90 Page 2 Page 2 of 9 FIN-2011-00084 VIZEUM CANADA INC. -

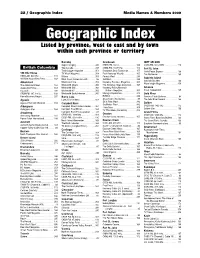

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance.