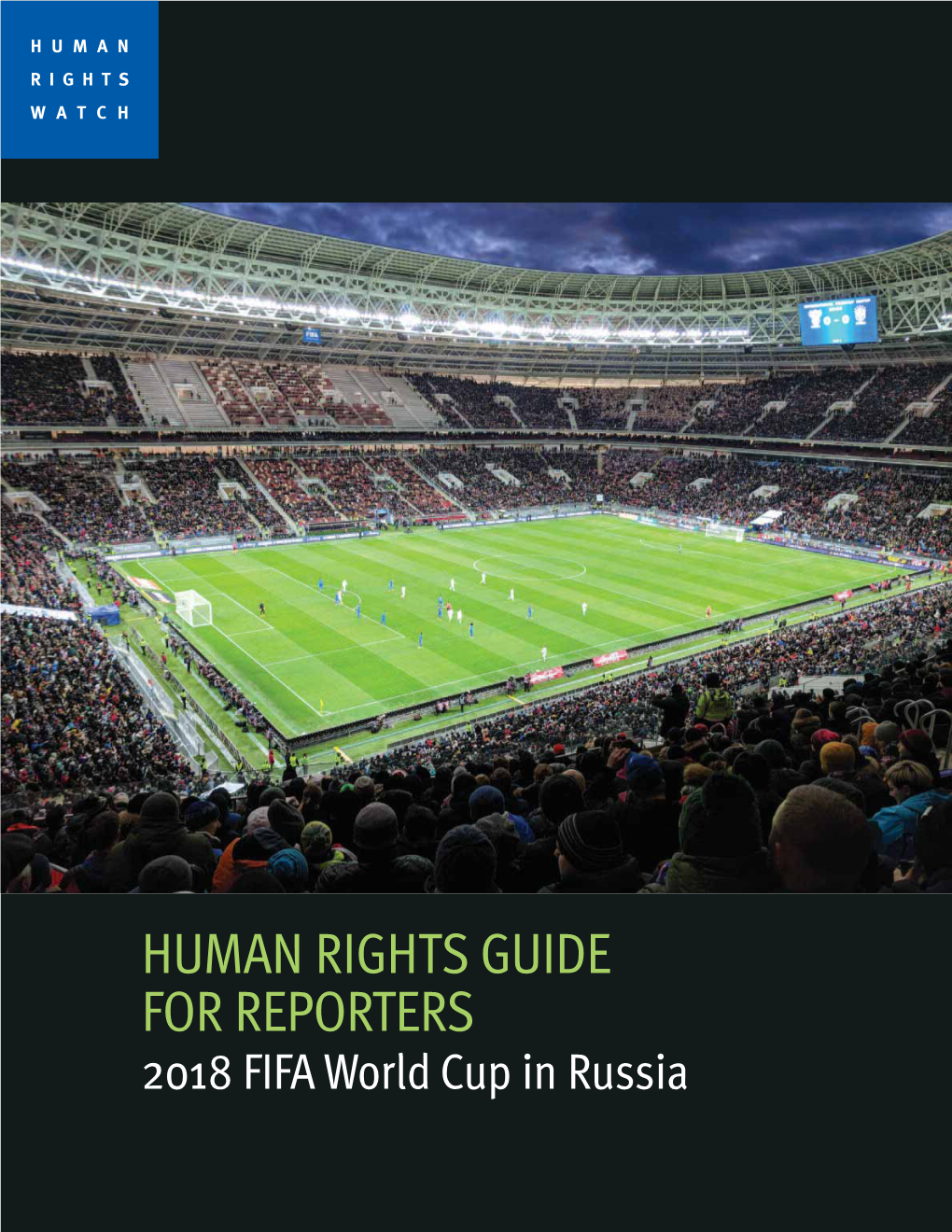

FIFA World Cup 2018 – Human Rights Guide for Reporters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Player Statistics Nigeria - Iceland 2 : 0 ( 0 : 0 ) # 24 22 JUN 2018 18:00 Volgograd / Volgograd Arena / RUS

2018 FIFA World Cup Russia™ Group D Player Statistics Nigeria - Iceland 2 : 0 ( 0 : 0 ) # 24 22 JUN 2018 18:00 Volgograd / Volgograd Arena / RUS Iceland Time played 98'37" 1 Hannes HALLDORSSON Goalkeeper 1st half 2nd half Total Team total Team avg * Goal(s) scored Shots 10 Assist(s) Offside(s) Save(s) 2 2 2 Yellow card 2Y+R/Red card Foul(s) committed 10 Delivery/solo runs into the attacking third 1/0 2/0 3/0 31/15 2.80/1.50 Delivery/solo runs into the penalty area 8/2 0.80/0.20 Tackles gaining/not gaining the ball 4/6 0.40/0.60 Tackles suffered losing/not losing the ball 1/5 0.10/0.50 Clearances completed/attempted 1/1 1/1 22/28 2.10/2.70 Activities 1st half 2nd half Total Team total Team avg * Total time played (mins) 47'06" 51'31" 98'37" 98'37" Zone 1: 0-7 km/h time spent (%) 92% 93% 92% 71% Zone 2: 7-15 km/h time spent (%) 8% 7% 7% 22% Zone 3: 15-20 km/h time spent (%) 1% 5% Zone 4: 20-25 km/h time spent (%) 2% Zone 5: >25 km/h time spent (%) Distance covered (metres) 2,783 2,914 5,697 106,021 10,032 Zone 1: 0-7 km/h distance covered (meters) 2,103 2,286 4,389 40,425 3,604 Zone 2: 7-15 km/h distance covered (meters) 606 584 1,190 42,792 4,160 Zone 3: 15-20 km/h distance covered (meters) 54 37 91 14,771 1,467 Zone 4: 20-25 km/h distance covered (meters) 8 7 15 6,166 615 Zone 5: >25 km/h distance covered (meters) 12 12 1,867 186 Top speed (km/h) 22.86 12.10 22.86 29.92 28.01 Sprints 1 1 359 36 * Team average does not include goalkeeper FIFA does not vouch for the accuracy of techinical statistics compiled in association with its competition results system partner. -

Luzhniki Stadium

ВСЕРОССИЙСКАЯ ОЛИМПИАДА ШКОЛЬНИКОВ ПО АНГЛИЙСКОМУ ЯЗЫКУ 2019 г МУНИЦИПАЛЬНЫЙ ЭТАП. 9 -11 классы Luzhniki Stadium Luzhniki Stadium is the national stadium of Russia, located in its capital city, Moscow. The full name of the stadium is Grand Sports Arena of the Luzhniki Olympic Complex. Its total seating capacity of 81,000 makes it the largest football stadium in Russia and one of the largest stadiums in Europe. Luzhniki was the main stadium of the 1980 Olympic Games, hosting the opening and closing ceremonies, as well as some of the competitions, including the final of the football tournament. A UEFA Category 4 stadium, Luzhniki hosted UEFA Cup Final in 1999 and UEFA Champions League Final in 2008 . The stadium also hosted such events as 1973 Summer Universiade and 2013 World Championships in Athletics. It was named the main stadium of 2018 FIFA World Cup and hosted 7 matches of the tournament, including the opening match and the final. Today it is mainly used as one of the home stadiums of the Russia national football team. The stadium is used from time to time for various other sporting events and for concerts. It is also used to host Russian domestic cup finals. Location The stadium is located in Khamovniki District of Moscow, south-west of the city center. The name Luzhniki derives from the flood meadows in the bend of the Moskva River where the stadium was built. History On 23 December 1954, the Government of the USSR adopted a resolution on the construction of a stadium in the Luzhniki area in Moscow. -

Portrait Master Template

2018 FIFA World Cup Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 An Accessible Matchday Experience ............................................................................................. 4 Purpose of this guide ..................................................................................................................... 5 Before arriving at the stadium ....................................................................................................... 5 Fan ID..................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Ticket Collection ................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Parking Passes ..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 At the stadiums.............................................................................................................................. 8 Accessible parking ......................................................................................................................................................... 9 Shuttle service ............................................................................................................................................................... -

Xenophobia As a Challenge to Positive Peace in Russia: Inter-Group Relations Within the Academia

Xenophobia as a Challenge to Positive Peace in Russia: Inter-group Relations Within The Academia Master’s Thesis in Peace, Mediation and Conflict Research Developmental Psychology Nikita Kordashenko, 1902049 Supervisor: Karin Österman Faculty of Education and Welfare Studies Åbo Akademi University, Finland Spring 2021 Nikita Kordashenko Abstract Aim: The aim of the study was to investigate positive attitudes towards integrating immigrant minorities, intense group identification, and psychological concomitants among Russian university students. Method: A questionnaire was completed by 129 females, 48 males, and three respondents who reported “other” as sex. The mean age was 19.8 (SD 2.6) for females and 21.8 (SD 2.9) for males. The age difference was significant. Results: Of females, 55.8 % and of males 66.7% reported that they knew some foreign student in person. Female students had a significantly more positive attitude towards integration immigrant minorities compared to male students. Male students scored slightly higher than female students on intense group identification. Respondents with low scores on positive attitudes towards integrating immigrants scored significantly higher on intense group identification. No significant differences were found for level of positive attitudes and anxiety and depression. Conclusions: More than half of the students knew some foreign student in person. Positive attitudes towards integrating immigrant minorities were overall high. There was a negative association between positive attitudes towards -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Uefa Euro 2020 Final Tournament Draw Press Kit

UEFA EURO 2020 FINAL TOURNAMENT DRAW PRESS KIT Romexpo, Bucharest, Romania Saturday 30 November 2019 | 19:00 local (18:00 CET) #EURO2020 UEFA EURO 2020 Final Tournament Draw | Press Kit 1 CONTENTS HOW THE DRAW WILL WORK ................................................ 3 - 9 HOW TO FOLLOW THE DRAW ................................................ 10 EURO 2020 AMBASSADORS .................................................. 11 - 17 EURO 2020 CITIES AND VENUES .......................................... 18 - 26 MATCH SCHEDULE ................................................................. 27 TEAM PROFILES ..................................................................... 28 - 107 POT 1 POT 2 POT 3 POT 4 BELGIUM FRANCE PORTUGAL WALES ITALY POLAND TURKEY FINLAND ENGLAND SWITZERLAND DENMARK GERMANY CROATIA AUSTRIA SPAIN NETHERLANDS SWEDEN UKRAINE RUSSIA CZECH REPUBLIC EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS 2018-20 - PLAY-OFFS ................... 108 EURO 2020 QUALIFYING RESULTS ....................................... 109 - 128 UEFA EURO 2016 RESULTS ................................................... 129 - 135 ALL UEFA EURO FINALS ........................................................ 136 - 142 2 UEFA EURO 2020 Final Tournament Draw | Press Kit HOW THE DRAW WILL WORK How will the draw work? The draw will involve the two-top finishers in the ten qualifying groups (completed in November) and the eventual four play-off winners (decided in March 2020, and identified as play-off winners 1 to 4 for the purposes of the draw). The draw will spilt the 24 qualifiers -

Racism in Russia and Its Effects on the Caucasian TESAM Akademi Dergisi - Turkish Journalregion of TESAM and Academy Peoples Ocak - January 2019

Can KAKIŞIM / Racism in Russia and its Effects on the Caucasian TESAM Akademi Dergisi - Turkish JournalRegion of TESAM and Academy Peoples Ocak - January 2019. 6(1). 97 - 121 ISSN: 2148 – 2462 RACISM IN RUSSIA AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE CAUCASIAN REGION AND PEOPLES1 Can KAKIŞIM2 Abstract Nowadays, Russia is one of those countries which crucially suffer from the racist sentiments and movements. In this country, radical right has an extensive social base and both ruling party and some other political entities can put forward examples of extreme nationalism. Caucasian-origin people have been the most negatively Caucasian immigrants from Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan asinfluenced well as group the Northernfrom these Caucasians approaches already since the holding beginning. Russian The citizenship have been target of numerous violent attacks especially in the 2000s. At the same time, rising racism in Russia strengthens expectations from the government to follow more active imperialist policies as racist groups more intensely defend and voice the rights of the Russians living in the former Soviet republics. Furthermore, between Russia and post-Soviet countries and in this sense, they these groups provide an additional fighting power in the clashes geography. compose a significant dimension of the interstate relations in this Keywords: Russia, Racism, Caucasia, Immigration, United Russia 1 Makalenin Geliş Tarihi: 15.04.2018 [email protected] Kabul Tarihi: 22.01.2019 2 Dr. Öğr. Üyesi, Karabük Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Uluslararası Atıf:İlişkiler Bölümü Öğretim Üyesi. e-mail: peoples. Tesam Akademi Dergisi - Kakışım C. (2019). Racism in Russia and its effects on the caucasian region and , 6(1), 97-121. -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

International Journal of Applied Exercise Physiology (IJAEP) ISSN: 2322 - 3537 [email protected]

International Journal of Applied Exercise Physiology 2322-3537 www.ijaep.com Vol.10 No.1 Doi:. 10.26655/IJAEP.2021.1.1 International Journal of Applied Exercise Physiology (IJAEP) ISSN: 2322 - 3537 www.ijaep.com [email protected] Editor-in-chief: Ali Reza Amani, PhD, Sport Science, Iran Editorial Board: Arnold Nelson, PhD, Louisiana State University, USA Chin, Eva R, PhD, University of Maryland, USA Hornsby, Guyton W, PhD, West Virginia University, USA J. Bryan Mann, PhD, University of Missouri, USA Michel Ladouceur, PhD, Dalhousie University, Canada MN Somchit, PhD, University Putra, Malaysia Stephen E Alway, PhD, West Virginia University, USA Guy Gregory Haff, Ph.D, Edith Cowan University, Australia Monèm Jemni, PhD, Cambridge University, UK Steve Ball, PhD, University of Missouri, USA Zsolt Murlasits, Ph.D., CSCS, Qatar University Ashril Yusof, Ph.D., University of Malaya Abdul Rashid Aziz, Ph.D., Sports Science Centre, Singapore Sports Institute Georgiy Polevoy, Ph.D, Vyatka State University, Russia International Journal of Applied Exercise Physiology www.ijaep.com VOL. 10 (1) Abstracting/Indexing ISI Master List Web of Science Core Collection (Emerging Sources Citation Index) by Thomson Reuters DOI (form Vol. 6(3) and after) ProQuest Centeral NLM (Pubmed) DOAJ COPERNICUS Master List 2017 PKP-PN, (LOCKSS & CLOCKSS) GS Crossref WorldCat Journal TOCs 2 International Journal of Applied Exercise Physiology www.ijaep.com VOL. 10 (1) Table of Contents The Relationship between Leisure Satisfaction and Hopelessness Yeşim Avunduk From Myth to -

The Russian 'Sovereign Internet' Facing Covid-19

The Russian ‘Sovereign Internet’ Facing Covid-19 Francesca Musiani, Olga Bronnikova, Françoise Daucé, Ksenia Ermoshina, Bella Ostromooukhova, Anna Zaytseva To cite this version: Francesca Musiani, Olga Bronnikova, Françoise Daucé, Ksenia Ermoshina, Bella Ostromooukhova, et al.. The Russian ‘Sovereign Internet’ Facing Covid-19. Institute of Network Cultures. Stefania Milan, Emiliano Treré & Silvia Masiero (eds.) COVID-19 from the Margins. Pandemic Invisibilities, Policies and Resistance in the Datafied Society, pp. 174-178, 2021, Theory on Demand #40, 978-94-92302-72-4. hal-03128294 HAL Id: hal-03128294 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03128294 Submitted on 2 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. COVID-19 FROM THE MARGINS PANDEMIC INVISIBILITIES, POLICIES AND RESISTANCE IN THE DATAFIED SOCIETY EDITED BY STEFANIA MILAN, EMILIANO TRERÉ AND SILVIA MASIERO A SERIES OF READERS PUBLISHED BY THE INSTITUTE OF NETWORK CULTURES ISSUE NO.: 40 174 THEORY ON DEMAND #40 30. THE RUSSIAN “SOVEREIGN INTERNET” FACING COVID-19 Francesca Musiani , Olga Bronnikova, Françoise Daucé, Ksenia Ermoshina, Bella Ostromooukhova & Anna Zaytseva Despite the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic in Russia, a state of emergency has not been declared in the country; only specific regions have entered into a state of “high alert” since early April. -

Information for Persons Who Wish to Seek Asylum in the Russian Federation

INFORMATION FOR PERSONS WHO WISH TO SEEK ASYLUM IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION “Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in the other countries asylum from persecution”. Article 14 Universal Declaration of Human Rights I. Who is a refugee? According to Article 1 of the Federal Law “On Refugees”, a refugee is: “a person who, owing to well‑founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of particular social group or politi‑ cal opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country”. If you consider yourself a refugee, you should apply for Refugee Status in the Russian Federation and obtain protection from the state. If you consider that you may not meet the refugee definition or you have already been rejected for refugee status, but, nevertheless you can not re‑ turn to your country of origin for humanitarian reasons, you have the right to submit an application for Temporary Asylum status, in accordance to the Article 12 of the Federal Law “On refugees”. Humanitarian reasons may con‑ stitute the following: being subjected to tortures, arbitrary deprivation of life and freedom, and access to emergency medical assistance in case of danger‑ ous disease / illness. II. Who is responsible for determining Refugee status? The responsibility for determining refugee status and providing le‑ gal protection as well as protection against forced return to the country of origin lies with the host state. Refugee status determination in the Russian Federation is conducted by the Federal Migration Service (FMS of Russia) through its territorial branches. -

Pedagogical Work of Mikhail M. Bakhtin (1920S – Early 1960S)1

ISSN: 2325-3290 (online) Pedagogical work of Mikhail M. Bakhtin (1920s – early 1960s)1 Vladimir I. Laptun Galin Tihanov M.I. Evsevyev Mordovia State Queen Mary University of London, Pedagogical Institute, Russia State UK Abstract The purpose of this essay to is to describe and discuss Bakhtin’s pedagogical work based on diverse archival materials and memoirs of his students. Vladimir I. Laptun, PhD., a senior lecturer of the Department of Education, M.I. Evsevyev Mordovia State Pedagogical Institute, Russia. His research interests include: life and pedagogical activity of Mikhail M. Bakhtin, history of pedagogy and education, comparative pedagogy, historical studies of local communities. Galin Tihanov is the George Steiner Professor of Comparative Literature at Queen Mary University of London. His most recent research has been on cosmopolitanism, exile, and transnationalism. His publications include four books and nine (co)edited volumes. Tihanov is winner, with Evgeny Dobrenko, of the Efim Etkind Prize for Best Book on Russian Culture (2012), awarded for their co-edited A History of Russian Literary Theory and Criticism: The Soviet Age and Beyond (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011). He is member of Academia Europaea and Honorary President of the ICLA Committee on Literary Theory. He is also on the Advisory Board of the Institute for World Literature (Harvard University) and is an honorary scientific advisor to the Institute of Foreign Literatures, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Tihanov has held visiting appointments at Yale University, St. Gallen University, University of Sao Paulo, Peking University, and Seoul National University. The life and legacy of the great Russian philosopher of the 20th century Mikhail Bakhtin (1895- 1975) have been analyzed in numerous studies.