Networking Surrealism in the USA. Agents, Artists and the Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTIST - DENNIS OPPENHEIM Born in Electric City, WA, USA, in 1938 Died in New York, NY, USA, in 2011

ARTIST - DENNIS OPPENHEIM Born in Electric City, WA, USA, in 1938 Died in New York, NY, USA, in 2011 EDUCATION - 1964 : Beaux Arts of California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, CA, USA 1967 : Beaux Arts of Stantford University, Palo Alto, CA, US SOLO SHOWS (SELECTION) - 2020 Dennis Oppenheim, Galerie Mitterrand, Paris, France 2019 Dennis Oppenheim, Le dessin hors papier, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen, FR 2018 Broken Record Blues, Peder Lund, Oslo NO Violations, Marlborough Contemporary, New York US Straight Red Trees. Alternative Landscape Components, Guild Hall, East Hampton, NY, US 2016 Terrestrial Studio, Storm King Art Center, New Windsor US Three Projections, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, US 2015 Collection, MAMCO, Geneva, CH Launching Structure #3. An Armature for Projections, Halle-Nord, Geneva CH Dennis Oppenheim, Wooson Gallery, Daegu, KR 2014 Dennis Oppenheim, MOT International, London, UK 2013 Thought Collision Factories, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, UK Sculpture 1979/2006, Galleria Fumagalli & Spazio Borgogno, Milano, IT Alternative Landscape Components, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, UK 2012 Electric City, Kunst Merano Arte, Merano, IT 1968: Earthworks and Ground Systems, Haines Gallery, San Francisco US HaBeer, Beersheba, ISR Selected Works, Palacio Almudi, Murcia, ES 2011 Dennis Oppenheim, Musee d'Art Moderne et Contemporain, Saint-Etienne, FR Eaton Fine Arts, West Palm Beach, Florida, US Galerie Samuel Lallouz, Montreal, CA Salutations to the Sky, Museo Fundacion Gabarron, New York, US 79 RUE DU TEMPLE -

Carleton a Florida B Oxford Brookes Rutgers A.Pdf

ACF Fall 2017 Edited by Jonathan Magin, Adam Silverman, Jason Cheng, Bruce Lou, Evan Lynch, Ashwin Ramaswami, Ryan Rosenberg, and Jennie Yang Packet by Carleton A, Florida B, Oxford Brookes, and Rutgers A Tossups 1. In 2010, this country drew international attention by passing an environmentalist act called the Law of the Rights of Mother Earth. An unpaved, winding road through this country’s Yungas region is infamous for being “the most dangerous road in the world.” A mountain overshadowing this country’s city of Potosi provided much of the silver ore that enriched Spain during the colonial era. The capital city of this country is the highest in the world because it lies on the Altiplano, most of which is located in this country. This country shares Lake Titicaca with its northwestern neighbor Peru. For 10 points, name this landlocked country in South America, with two capitals: Sucre and La Paz. ANSWER: Bolivia 2. One of this author’s title characters declares “We shall yet make these United States a moral nation!” after blackmailing Hettie Dowler to prevent her from going public with their affair. Another of his main characters joins her town’s Thanatopsis reading club, but is forced to put on a mediocre play called The Girl From Kankakee. This author wrote a novel whose hypocritical title character becomes the lover of Sharon Falconer before leading a congregation in Zenith. In another novel by this author, Carol Kennicott attempts to change the bleak small-town life of Gopher Prairie. For 10 points, name this American author of Elmer Gantry and Main Street. -

Ata Arte E Esoterismo V2.Pdf

Índice 4 Teresa Lousa, Arte e Esoterismo Ocidental 5 Luís Campos Ribeiro, Estrelas, cometas e profecia: a conjugação de arte, ciência e astrologia em Portugal no século XVII 33 Manuela Soares, A Evolução da Mão 42 Jorge Tomás Garcia, Un Tiempo nuevo: representacionesde Aión en la musivaria romana 59 Salomé Marivoet, O Espiritual na Pintura Contemporânea. Contributos das obras escritas e artísticas de Kandinsky e Rothko ao estudo do transcendental místico na linguagem pictórica 85 Dora Iva Rita, Uma narrativa inesperada numa pintura do Martírio de S. Sebastião 97 Inês Henriques Garcia, Bosch, fantasia e espiritualidade: Uma relação intrínseca 110 João Peneda, Kadinsky e o “Espiritual na arte” 124 Roger Ferrer Ventosa, Representaciones artísticas del no dualismo 136 Júlio Mendes Rodrigo, O Andrógino Hermético: um “Ser Duplo” através das Artes e das Letras 145 Marjorie E. Warlick, Alchemy and other Esoteric Traditions in Surrealist Art 156 Anna Váraljai, Theosophic Art and Theosophic Aesthetic in Hungary – In Ten Years, in the Aspect of the Theosophical Society Journal (1912-1928) 166 Isabel da Rocha, úsica e os fenómenos do Universo e do Ser Humano, na tradição Pitagórica 182 Mariana Bernardo Nunes, Os 5 âmbitos de cura de Paracelso em comparação com o conceito de cura de Hagane no Renkinjutsushi 196 Miguel Ribeiro-Pereira, Major/Minor Harmony And Modern Human Consciousness – An Anthroposophical And Musical Approach To Laughing And Weeping 210 Arilson Oliveira, O Simbolismo De “O Nome Da Rosa” – Entre Flores Secretas E Risos Em Lumes Simpósio Temático: Arte e Esoterismo Ocidental Coordenação: Teresa Lousa (UL) A arte constitui, tal como muitas outras áreas do saber, um veículo de expressão e de comunicação de conhecimentos interiores, sendo considerada pela Gnosis uma das quatro colunas do conhecimento, em conjunto com a Ciência, a Filosofia e a Religião. -

The Thessaloniki Biennale: the Agendas and Alternative Potential(S) of a Newly-Founded Biennial in the Context of Greek Governance

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Karavida, Aikaterini (2014). The Thessaloniki Biennale: The agendas and alternative potential(s) of a newly-founded biennial in the context of Greek governance. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/13704/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Thessaloniki Biennale: The agendas and alternative potential(s) of a newly-founded biennial in the context of Greek governance Volume 2 Aikaterini Karavida This thesis is submitted as part of the requirements for the award of the PhD in ARTS POLICY AND MANAGEMENT CITY UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF CULTURE AND CREATIVE INDUSTRIES July 2014 1 Table of Contents -

CIES E-Working Paper N.º 167/2013 Andy Warhol Com Leonardo: De

CIES e-Working Paper N.º 167/2013 Andy Warhol com Leonardo: de Monalisa a Cristo (3.ª parte) Idalina Conde CIES e-Working Papers (ISSN 1647-0893) Av. das Forças Armadas, Edifício ISCTE, 1649-026 LISBOA, PORTUGAL, [email protected] Idalina Conde é docente na Escola de Sociologia e Políticas Públicas do ISCTE-IUL Instituto Universitário de Lisboa e investigadora no CIES. Leciona no Mestrado em Comunicação, Cultura e Tecnologias da Informação do ISCTE-IUL. Anteriormente, também no curso de pós-graduação em Gestão Cultural nas Cidades do INDEG/ISCTE, a par de várias formações noutras instituições. Paralelamente ao CIES, colaborou em projetos do ERICARTS, The European Institute for Comparative Cultural Research no OAC – Observatório das Atividades Culturais. É autora de numerosas publicações no domínio da sociologia da arte e da cultura, bem como sobre abordagens biográficas. Tem realizado diversos cursos e workshops nessas áreas, nomeadamente sobre criatividade, receção cultural e relações da arte contemporânea com a memória e o património europeu. E-mail: [email protected] Resumo No arco de 20-25 anos, Andy Warhol usou em diferentes momentos imagens de três obras de Leonardo da Vinci: Monalisa, Anunciação e A Última Ceia. Baseando-se nelas fez Thirty Are Better Than One, em 1963, uma versão da Anunciação na série Details of Renaissance Paintings, em 1984 (juntamente com obras de Sandro Botticelli, Piero della Francesca, Paolo Uccello), e The Last Supper, em 1986, com muitas variações, incluindo a maior, The Last Supper (Christ 112 Times) (1986). O texto reflete sobre essa trajetória procurando o sentido dos encontros de Warhol com Leonardo, entre outras obras-primas da Renascença que também incluíram (em 1985) a Madonna Sistina de Rafael Sanzio. -

The Permanent Rebellion of Nicolas Calas: the Trotskyist Time Forgot Wald, Alan

The Permanent Rebellion of Nicolas Calas: The Trotskyist Time Forgot Wald, Alan. Against the Current; Detroit Vol. 33, Iss. 4, (Sep/Oct 2018): 27-35. Abstract Foyers d'incendie, which has never been fully translated into English, involves a reworking of Freud's idea of the pleasure principle (behavior directed toward immediate satisfaction of instinctual drives and reduction of pain) to include a desire to change the future. [...] rather than following Freud in accepting civilization as necessary repression, Calas was adamant in posing a revolutionary alternative: "Since desire cannot simply do as it pleases, it is forced to adopt an attitude toward reality, and to this end it must either try to submit to as many of the demands of its environment as possible, or try to transform as far as possible everything in its environment which seems contrary to its desires. According to Schapiro, Breton chose van Heijenoort and Calas to defend dialectical materialism, while Schapiro arranged for Columbia philosopher of science Ernest Nagel and British logical positivist A. J. Ayer (then working for the British government on assignment in the United States) to raise objections. Exponents such as Larry Rivers, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns often drew on advertising, comic books and mundane cultural objects to convey an irony accentuating the banal aspects of United States culture. Since Pop Art used a style that was hard-edged and representational, it has been interpreted as a reaction against Abstract Expressionism, the post-World War II anti-figurative aesthetic that emphasizes spontaneous brush strokes or the dripping and splattering of paint. -

The Greek Sale

athens nicosia The Greek Sale thursday 8 november 2018 The Greek Sale nicosia thursday 8 november, 2018 athens nicosia AUCTION Thursday 8 November 2018, at 7.30 pm HILTON CYPRUS, 98 Arch. Makarios III Avenue managing partner Marinos Vrachimis partner Dimitris Karakassis london representative Makis Peppas viewing - ATHENS athens representative Marinos Vrachimis KING GEORGE HOTEL, Syntagma Square for bids and enquiries mob. +357 99582770 mob. +30 6944382236 monday 22 to wednesday 24 october 2018, 10 am to 9 pm email: [email protected] to register and leave an on-line bid www.fineartblue.com viewing - NICOSIA catalogue design Miranda Violari HILTON CYPRUS, 98 Arch. Makarios III Avenue photography Vahanidis Studio, Athens tuesday 6 to wednesday 7 november 2018, 10 am to 9 pm Christos Panayides, Nicosia thursday 8 november 2018, 10 am to 6 pm exhibition instalation / art transportation Move Art insurance Lloyds, Karavias Art Insurance printing Cassoulides MasterPrinters ISBN 978-9963-2497-2-5 01 Yiannis TSAROUCHIS Greek, 1910-1989 The young butcher signed and dated ‘68 lower right gouache on paper 16.5 x 8.5 cm PROVENANCE private collection, Athens 1 800 / 3 000 € Yiannis Tsarouchis was born in 1910 in Piraeus, Athens. In 1928 he enrolled at the School of Fine Art, Athens to study painting under Constantinos Parthenis, Spyros Vikatos, Georgios Iakovides and Dimitris Biskinis, graduating in 1933. Between 1930 and 1934, he also studied with Fotis Kondoglou who introduced him to Byzantine painting. In 1935, Tsarouchis spend a year in Paris, where he studied etching at Hayterre studio; his fellow students included Max Ernest and Giacometti. -

Themenilcollection

To S. Shepherd 1.5 miles West Alabama west Parking n o t s u o MENIL BISTRO H A John & Dominique , MENIL TH E COLLECTION n BOOKS TORE o s t r de Menil e Sul Ros s b o R - e y e e MENIL y k l s The story of the Menil c Rothko i r l D E F n Guide H o r e Chapel : r o e G d m Universi ty of t Collection begins in France o B C p b t n t n l o u a St. Thomas b o u THE MENI L Y with the 1931 marriage of o s t i r M M M p COL LECTI ON a o P H t , John de Menil (190 4–73 ), , P s h G p A a r Branard D a young banker from a g A o / t o k k h CY TWOMBLY r P o r mili tary family, and Y a GALLERY w John and Dominique de Menil, 1967 t BYZANTINE n e o s t N Dominique Schlumberger s FRESCO , u u ) o S a R CHAPEL H West Mai n r , A (1908–97), daughter of Conrad Schlum berger, one of the ( n o y G s o t t e t r Parking i e c t founders of the oil services company Schlumberger, Ltd. b o S e o R s r t Max Ernst, - y h o The de Menils left France during World War II, making e g i k R c L Le surreálisme et i Col quitt s H t s : Col quitt i their way to Houston, where John would eventually direct la peinture (Surrealism t h r p A a and Painting ), 1942 r 5 g 1 Schlumberger’s worldwide operations. -

Interpreting Art : Reflecting, Wondering, and Responding

E>»isa S' oc 3 Interpreting Art Interpreting Art Reflecting, Wondering, and Responding Terry Barrett The Ohio State University Boston Burr Ridge, IL Dubuque, IA Madison, Wl New York San Francisco St. Louis Bangkok Bogota Caracas Kuala Lumpur Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan Montreal New Delhi Santiago Seoul Singapore Sydney Taipei Toronto McGraw-Hill Higher Education gg A Division of The McGraw-Hill Companies Interpreting Art: Reflecting, Wondering, and Responding Published by McGraw-Hill, an imprint of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 1221 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020. Copyright ® 2003 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written consent of The McGraw- Hill Companies, Inc., including, but not limited to, in any network or other electronic storage or transmission, or broadcast for distance learning. This book is printed on acid-free paper. 34567890 DOC/DOC 0 9 8 7 6 5 4 ISBN 0-7674-1648-1 Publisher: Chris Freitag Sponsoring editor: Joe Hanson Marketing manager: Lisa Berry Production editor: David Sutton Senior production supervisor: Richard DeVitto Designer: Sharon Spurlock Photo researcher: Brian Pecko Art editor: Emma Ghiselli Compositor: ProGraphics Typeface: 10/13 Berkeley Old Style Medium Paper: 45# New Era Matte Printer and binder: RR Donnelley & Sons Because this page cannot legibly accommodate all the copyright notices, page 249 constitutes an extension of the copyright page. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Barrett, Terry Michael, 1945- Interpreting Art: reflecting, wondering, and responding / Terry Barrett, p. -

Marlborough Gallery

Marlborough DENNIS OPPENHEIM 1938 — Born in Electric City, Washington 2011 — Died in New York, New York The artist lived and worked in New York, New York. Education 1965 — B.F.A., the School of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, California 1966 — M.F.A., Stanford University, Palo Alto, California Solo Exhibitions 2020 — Dennis Oppenheim, Galerie Mitterand, Paris, France 2019 — Feedback: Parent Child Projects from the 70s, Shirley Fiterman Art Center, The City University of New York, BMCC, New York, New York 2018 — Violations, 1971 — 1972, Marlborough Contemporary, New York, New York Broken Record Blues, Peder Lund, Oslo, Sweden 2016 — Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York 2015 — Wooson Gallery, Daegu, Korea MAMCO, Geneva, Switzerland Halle Nord, Geneva, Switzerland 2014 — MOT International, London, United Kingdom Museo Magi'900, Pieve di Cento, Italy 2013 — Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, United Kingdom Museo Pecci Milano, Milan, Italy Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Yorkshire, United Kingdom Marlborough 2012 — Centro de Arte Palacio, Selected Works, Murcia, Spain Kunst Merano Arte, Merano, Italy Haines Gallery, San Francisco, California HaBeer, Beersheba, Israel 2011 — Musée d'Art moderne Saint-Etienne Metropole, Saint-Priest-en-Jarez, France Eaton Fine Arts, West Palm Beach, Florida Galerie Samuel Lallouz, Quebec, Canada The Carriage House, Gabarron Foundation, New York, New York 2010 — Thomas Solomon Gallery, Los Angeles, California Royale Projects, Indian Wells, California Buschlen Mowatt Galleries, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Galleria Fumagalli, Bergamo, Italy Gallerie d'arts Orler, Venice, Italy 2009 — Marta Museum, Herford, Germany Scolacium Park, Catanzaro, Italy Museo Marca, Catanzarto, Italy Eaton Fine Art, West Palm Beach, Florida Janos Gat Gallery, New York, New York 2008 — Ace Gallery, Beverly Hills, California 4 Culture Gallery, Seattle, Washington Edelman Arts, New York, New York D.O. -

Download Press Release (PDF)

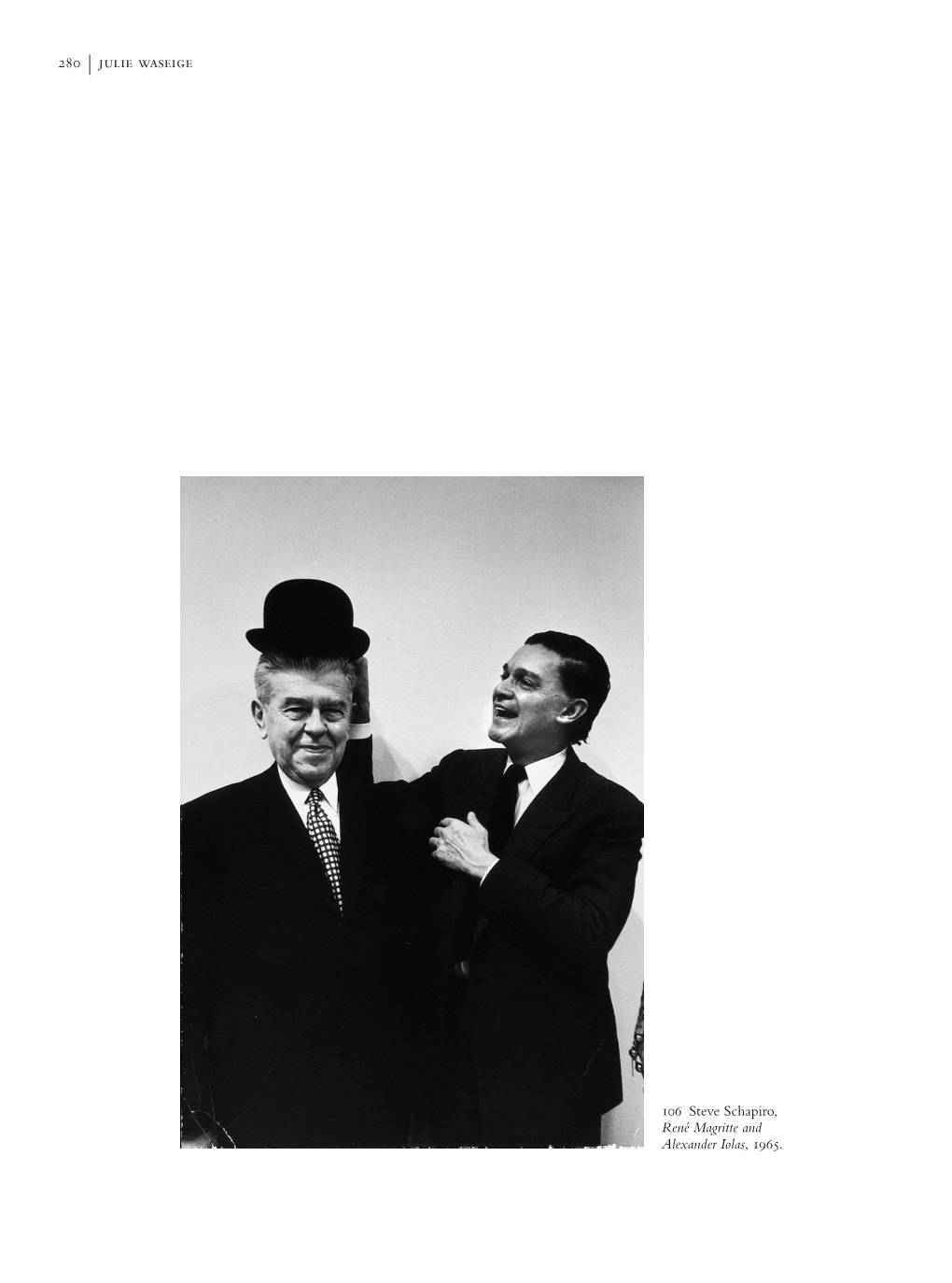

Alexander the Great: The Iolas Gallery 1955-1987 March 6 – April 26, 2014 Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York 293 10th Avenue Opening Reception: Thursday, March 6, 2014, 6 – 8 PM Paul Kasmin Gallery is pleased to announce the forthcoming exhibition Alexander the Great: The Iolas Gallery 1955-1987, which will showcase work by many major artists whose careers were defined through their work with influential 20th century art dealer Alexander Iolas. The exhibition will be on view from March 6 – April 26, 2014 at 293 10th Avenue. Alexander the Great is organized in collaboration with Vincent Fremont and Adrian Dannatt. A comprehensive monograph will be published at the time of the exhibition and will include a foreword by Bob Colacello, extensive interviews and essay by Adrian Dannatt, and archival material provided by The William N. Copley Estate, The Fontana Foundation, The Yves Klein Archives, The Jules Olitski Estate, The Takis Foundation, The Estate of Dorothea Tanning, and The Andy Warhol Foundation. Iolas played a pivotal role in twentieth century art in America. He is recognized for being among the first to introduce American audiences to Surrealism, mounting Andy Warhol’s first gallery exhibition, and being an artist’s advocate who championed work according to his own tastes, rather than popular trends. Iolas was known throughout his career as a passionate art lover who built deep personal relationships and facilitated intercontinental connections among artists, gallerists, and collectors via his eponymous galleries in Athens, Geneva, Madrid, Milan, New York and Paris. His influence spread to arts patrons as well. His close work with Dominique de Menil, for example, helped to define and build her collection. -

Networking Surrealism in the USA. Agents, Artists and the Market

135 Magritte at the Rodeo: René Magritte in the Menil Collection Clare Elliott In the late 1940s, John1 and Dominique (born Schlumberger) de Menil’s attention was drawn to the enigmatic images of familiar objects by the Belgian surrealist artist René Magritte. Over the course of the next forty years, the couple established a critically acclaimed collection of paintings, sculpture, and drawings by Magritte in the United States, which are now housed at the museum that bears their name in their chosen home of Houston, Texas. Multifaceted, experimental collectors with strong philosophical inclinations, the de Menils relished Magritte’s provocations and his continual questioning of bourgeois convention. In 1993, Dominique described the qualities that attracted her and John to Magritte’s work: “He was very serious in dealing with the great pro- blem of who are we? What is the world? What are we doing on earth? What is after life? Is there anything?”2 A focused look at the formation of this particular aspect of their holdings allows insight into the ambi- tious goals that animated the de Menils and reveals the frequent and sometimes unexpected ways in which the networks of surrealism—gal- leries, collectors, museums, and scholars—intersected and overlapped in the United States in the second half of the twentieth century.3 1 Born Jean de Menil, he anglicized his name when he took American citizenship in 1962. 2 Quoted in Susie Kalil, “Magical Magritte Maze at the Menil,” Houston Press, January 21, 1993, p. 31. 3 For this paper I have consulted in addition to published sources the archives available to me as a curator at the Menil Collection: the object files initiated by John de Menil and added to over the years by researchers and museum staff; interviews given by the de Menils and their dealer Alexander Iolas; and material in the Menil Collection Archives, particularly the documents rela- ting to their involvement in the Hugo and Iolas Galleries, which were restricted until 2013, but are now available to researchers.