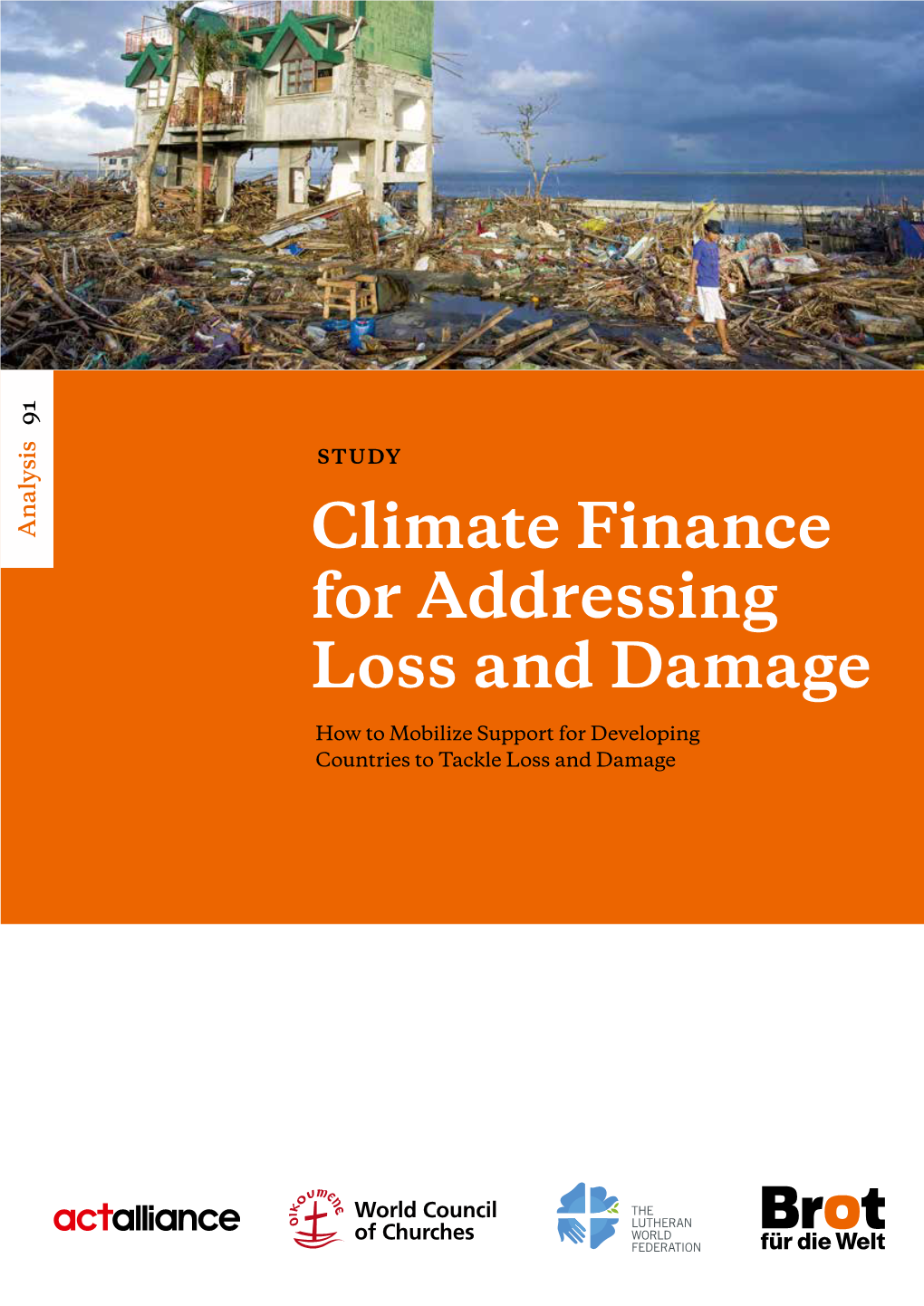

Climate Finance for Addressing Loss and Damage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pure Magazine

PURE MAGAZINOctobeEr 2017 Jack O’Rourke Talks Music, Electric Picnic, Father John Misty and more… The Evolution Of A Modern Gentleman Jimmy Star chats with Hollywood actor... Sean Kanan Sony’s VR capabilities establishes them as serious contenders in the Virtual Reality headset war! Eli Lieb Talks Music, Creating & Happiness… Featured Artist Dionne Warwick Marilyn Manson Cheap Trick Otherkin Eileen Shapiro chats with award winning artist Emma Langford about her Debut + much more EalbumM, tour neMws plus mAore - T urLn to pAage 16 >N> GFORD @PureMzine Pure M Magazine ISSUE 22 Mesmerising WWW.PUREMZINE.COM forty seven Editor in Chief Trevor Padraig [email protected] and a half Editorial Paddy Dunne [email protected] minutes... Sarah Swinburne [email protected] Shane O’ Rielly [email protected] Marilyn Manson Heaven Upside Down Contributors Dave Simpson Eileen Shapiro Jimmy Star Garrett Browne lt-rock icon Marilyn Manson is back “Say10” showcases a captivatingly creepy Danielle Holian brandishing a brand new album coalescence of hauntingly hushed verses and Simone Smith entitled Heaven Upside Down. fantastically fierce choruses next as it Irvin Gamede ATackling themes such as sex, romance, saunters unsettlingly towards the violence and politics, the highly-anticipated comparatively cool and catchy “Kill4Me”. Front Cover - Ken Coleman sequel to 2015’s The Pale Emperor features This is succeeded by the seductively ten typically tumultuous tracks for fans to psychedelic “Saturnalia”, the dreamy yet www.artofkencoleman.com feast upon. energetic delivery of which ensures it stays It’s introduced through the sinister static entrancing until “Je$u$ Cri$i$” arrives to of “Revelation #12” before a brilliantly rivet with its raucous refrain and rebellious bracing riff begins to blare out beneath a instrumentation. -

IN the MOUNTIES WE TRUST: a Study of Royal Canadian Mounted

IN THE MOUNTIES WE TRUST: A Study of Royal Canadian Mounted Police Accountability by STEPHEN LORENZ WETTLAUFER A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada July, 2011 Copyright © Stephen Lorenz Wettlaufer, 2011 Abstract Police and Canadian citizens often clash during protests sometimes resulting in violent outcomes. Due to the nature of those altercations, there are few other events that require oversight more than the way police clash with protesters and there is a history of such oversight resulting in a number of Federal Parliamentary documents, Parliamentary Committee reports Task Force reports, reports arising from Public Interest Hearings of the Commission for Complaints Against the RCMP, and testimony at various hearings and inquiries which have produced particular argumentative discourses. Argumentative discourses that have a great effect on the construction of a civilian oversight agency of the RCMP is the focus of this thesis. This thesis examines how it is that different discourses, as represented by argumentative themes in these reports, intersect with one another in the process of creating a system of accountability for the RCMP. Through the lens of complaints that arise from protest and police clashes one may conclude that the current system of accountability does not adhere to a practice of protecting the most fundamental rights as prescribed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms; nor would the currently proposed legislation contained within Bill C‐38 alter the system in a substantial way to allow for such protections. The power dynamic between the Commissioner of the Force and the Commission for Complaints Against the RCMP favours the police force in the current and proposed system. -

Towards Transformative Climate Justice: Key Challenges and Future Directions for Research

:RUNLQJ3DSHU 9ROXPH 1XPEHU 7RZDUGV7UDQVIRUPDWLYH &OLPDWH-XVWLFH.H\ &KDOOHQJHVDQG)XWXUH 'LUHFWLRQVIRU5HVHDUFK 3HWHU1HZHOO6KLOSL6ULYDVWDYD/DUV2WWR1DHVV *HUDUGR$7RUUHV&RQWUHUDVDQG5R]3ULFH -XO\ 7KH,QVWLWXWHRI'HYHORSPHQW6WXGLHV ,'6 GHOLYHUVZRUOGFODVVUHVHDUFK OHDUQLQJDQGWHDFKLQJWKDWWUDQVIRUPVWKHNQRZOHGJHDFWLRQDQGOHDGHUVKLS QHHGHGIRUPRUHHTXLWDEOHDQGVXVWDLQDEOHGHYHORSPHQWJOREDOO\ ,QVWLWXWHRI'HYHORSPHQW6WXGLHV :RUNLQJ3DSHU 9ROXPH 1XPEHU 7RZDUGV7UDQVIRUPDWLYH&OLPDWH-XVWLFH.H\&KDOOHQJHVDQG)XWXUH'LUHFWLRQVIRU5HVHDUFK 3HWHU1HZHOO6KLOSL6ULYDVWDYD/DUV2WWR1DHVV*HUDUGR$7RUUHV&RQWUHUDVDQG5R]3ULFH -XO\ )LUVWSXEOLVKHGE\WKH,QVWLWXWHRI'HYHORSPHQW6WXGLHVLQ-XO\ ,661 ,6%1 $FDWDORJXHUHFRUGIRUWKLVSXEOLFDWLRQLVDYDLODEOHIURPWKH%ULWLVK/LEUDU\ 7KLVZRUNZDVFDUULHGRXWZLWKWKHDLGRIDJUDQWIURPWKH,QWHUQDWLRQDO'HYHORSPHQW5HVHDUFK&HQWUH 2WWDZD&DQDGD7KHYLHZVH[SUHVVHGKHUHLQGRQRWQHFHVVDULO\UHSUHVHQWWKRVHRIWKH,QVWLWXWHRI 'HYHORSPHQW6WXGLHVRU,'5&DQGLWV%RDUGRI*RYHUQRUV 7KLVLVDQ2SHQ$FFHVVSDSHUGLVWULEXWHGXQGHUWKHWHUPVRIWKH&UHDWLYH&RPPRQV $WWULEXWLRQ1RQ&RPPHUFLDO,QWHUQDWLRQDOOLFHQFH &&%<1& ZKLFKSHUPLWVXVH GLVWULEXWLRQDQGUHSURGXFWLRQLQDQ\PHGLXPSURYLGHGWKHRULJLQDODXWKRUVDQGVRXUFHDUH FUHGLWHGDQ\PRGLILFDWLRQVRUDGDSWDWLRQVDUHLQGLFDWHGDQGWKHZRUNLVQRWXVHGIRUFRPPHUFLDOSXUSRVHV $YDLODEOHIURP ,QVWLWXWHRI'HYHORSPHQW6WXGLHV/LEUDU\5RDG %ULJKWRQ%15(8QLWHG.LQJGRP LGVDFXN ,'6LVDFKDULWDEOHFRPSDQ\OLPLWHGE\JXDUDQWHHDQGUHJLVWHUHGLQ(QJODQG &KDULW\5HJLVWUDWLRQ1XPEHU &KDULWDEOH&RPSDQ\1XPEHU 3 Working Paper Volume 2020 Number 540 Towards Transformative Climate Justice: Key Challenges -

PLAYBOOK for CLIMATE FINANCE Innovative Strategies to Finance a Cooler, Safer Planet

PLAYBOOK FOR CLIMATE FINANCE Innovative strategies to finance a cooler, safer planet Playbook for Climate Finance 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Introduction 4 What is Climate Finance? 5 How Climate Finance is Taking Shape How We Do It 6 Carbon Pricing 8 Impact Investment 11 Blue Bonds for Conservation 13 Insuring Natural Infrastructure 15 Leveraging Multilateral Funding Sources 16 Conclusion Playbook for Climate Finance 2 INTRODUCTION Every day, we see the toll climate change takes on our planet. It represents an immediate threat to economic security and prosperity, as well as the physical health of human and natural communities. But addressing climate change is an opportunity for innovation in all facets of human life—in how we provide food and goods for a growing population, provide clean and affordable energy for communities, design healthy and livable cities, conserve and protect lands and oceans, and provide water security for future generations. Many of the tools and resources we need to tackle climate change already exist, and human innovation keeps creating new possibilities. However, the window of opportunity is closing. This is the critical decade to reduce risks of catastrophic climate change, major biodiversity loss and other environmental problems that are increasing human suffering. The COVID-19 pandemic is undoubtedly a setback, of course, creating a level of global system shock not witnessed since World War II. But the current crisis has also shown our collective vulnerability—and our collective capacity to mobilize rapidly and decisively against threats that have no regard for international borders, such as climate change. It’s up to our leaders as well as every single one of us to decide whether we allow this era to be defined by inaction and frustration, leading to devastating impacts, or whether it’s a springboard to a better world. -

Slow-Onset Processes and Resulting Loss and Damage

Publication Series ADDRESSING LOSS AND DAMAGE FROM SLOW-ONSET PROCESSES Slow-onset Processes and Resulting Loss and Damage – An introduction Table of contents L 4 22 ist of a bbre Summary of Loss and damage via tio key facts and due to slow-onset ns definitions processes AR4 IPCC Fourth Assessment Report 6 22 What is loss and damage? Introduction AR5 IPCC Fifth Assessment Report COP Conference of the Parties to the 23 United Nations Framework Convention on 9 What losses and damages IMPRINT Climate Change can result from slow-onset Slow-onset ENDA Environment Development Action Energy, processes? Authors Environment and Development Programme processes and their Laura Schäfer, Pia Jorks, Emmanuel Seck, Energy key characteristics 26 Oumou Koulibaly, Aliou Diouf ESL Extreme Sea Level What losses and damages Contributors GDP Gross Domestic Product 9 can result from sea level rise? Idy Niang, Bounama Dieye, Omar Sow, Vera GMSL Global mean sea level What is a slow-onset process? Künzel, Rixa Schwarz, Erin Roberts, Roxana 31 Baldrich, Nathalie Koffi Nguessan GMSLR Global mean sea level rise 10 IOM International Organization on Migration What are key characteristics Loss and damage Editing Adam Goulston – Scize Group LLC of slow-onset processes? in Senegal due to IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change sea level rise Layout and graphics LECZ Low-elevation coastal zone 14 Karin Roth – Wissen in Worten OCHA Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs What are other relevant January 2021 terms for the terminology on 35 RCP Representative -

VIP Visits DIPLOMATIC BLUEBOOK 2006

VIP Visits DIPLOMATIC BLUEBOOK 2006 VIP Visits January 1, 2005-December 31, 2005 <VIP Visits covered in this table and notes> 1. The period covered in this table is from January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2005. 2. Regarding visits by Japanese VIPs, the visits to other countries have been listed for the Imperial Family, the Prime Minister, Special Envoys of the Prime Minister, Cabinet Ministers, Senior-Vice Ministers for Foreign Affairs, Parliamentary Secretaries for Foreign Affairs, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, and the President of the House of Councillors. 3. Regarding visits by VIPs from other countries and institutions, this list principally includes VIPs of or above the rank of foreign minister in each country as well as the heads of each international organization who 1) either met with Japanese VIPs of or above the rank of Minister for Foreign Affairs or 2) had the purpose of attending international conferences held in Japan. 4. Meetings that were held with VIPs from third-party countries on occasions when Japanese VIPs attended international conferences are listed in the column “Purpose of visit and main schedule” of the visits to the host country of the conference. 5. The titles of VIPs are those held at the time when the visits were made. 6. The period refers to the duration of stay in the country or region that VIPs were visiting. Name of country or region Name of VIP Period Purpose of visit and main schedule (1) Asia and the Pacific Australia ToSenior Vice-Foreign Minister 2/10-2/13 Attendance at the Third Australia-Japan -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

B Efforts Aimed at Realizing Prosperity in the International Community

CHAPTER 3 JAPAN’S FOREIGN POLICY IN MAJOR DIPLOMATIC FIELDS BEfforts Aimed at Realizing Prosperity in the International Community Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the Overview Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM), and of multilayered eco- The global economy in 2004 generally made a steady re- nomic relations, including those between Japan and the covery, despite instability caused by rising crude oil United States (US) as well as Japan and Europe. The prices and some other factors. fourth is strengthening economic security, including in Under these circumstances, Japan has promoted the areas of energy, food, marine issues, piracy, and fish- economic foreign policy focusing on the following five eries (including whaling). The final one is support for issues as its priorities, with the objective of further Japanese companies overseas and the promotion of in- strengthening the economies of both Japan and the vestments to Japan. world. The first is maintaining and strengthening the Moreover, while the international community ac- multilateral trading system (global efforts) and promot- knowledges the importance of science and technology ing economic partnership at the regional and bilateral to resolve various global issues, Japan has been advanc- levels to complement the multilateral trading system. ing bilateral and multilateral cooperation, using its ex- The second is active participation in international efforts perience as the world leader in science and technology. on globalization aimed at coping effectively with global While Japan has been making efforts to enhance its issues, such as working on world economic growth and own economic interests, it also endeavors to respond ef- sustainable development. The third is strengthening fectively to these various issues in pursuit of the pros- frameworks for interregional cooperation such as the perity of the international community. -

Climate Finance Tracking Guidance Manual

1 Table of contents 1. General introduction ......................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Rationale for tracking climate finance ................................................................................... 4 1.2 Climate finance tracking in the AfDB ..................................................................................... 5 1.3 Outline of the structure of guidance ..................................................................................... 5 2. Preparing for tracking climate finance ................................................................................ 7 2.1 When does climate finance tracking take place? .................................................................. 7 2.2 To what is this guidance applied? ......................................................................................... 7 2.3 Who is responsible? .............................................................................................................. 7 2.4 What information is required? .............................................................................................. 7 2.5 How are the results reported? .............................................................................................. 8 3. How to track climate finance ............................................................................................. 9 3.1 STEP 1: Define qualifying project elements .......................................................................... -

Climate Finance in the Urban Context

DEVELOPMENT · CLIMATE · AND FINANCE Climate Finance in the Urban Context November 2010 COSTS OF ADAPTATION AND MITIGATION IN CITIES ISSUES BRIEF #4 A good deal of climate-resilient development in the urban Cities and the people who live in them context simply means good, robust development. Potential climatic changes pose additional challenges in building account for more than 80 percent of the infrastructure that can withstand extreme variations in world’s total greenhouse gas emissions. In weather conditions, such as flooding, wind storms, heat waves, and heavy snowfall. Increasingly the work toward addition, more than 80 percent of the over- the Millennium Development Goals and related urban all annual global costs of adaptation to infrastructure should be screened for the potential impacts and increased costs associated with a changing climate. climate change are estimated to be borne by urban areas. This Issues Brief looks at There is an incremental cost to climate-resilient develop- potential financing opportunities and costs ment for which cities are seeking additional financing. Cities are also the largest emitters of greenhouse gases of mitigation and adaptation in the urban (GHGs) and are experiencing increased costs as they move context. Wide-ranging potential sources for toward low-carbon development paths—that is, mitigat- ing GHG emissions. finance for climate action are described, and suggestions are made for more- When addressing adaptation and mitigation costs, the effective responses to climate investment broad range of financing needs includes: challenges in cities. • Upstream planning for the provision of urban services • Prefeasibility and feasibility analysis of investments • Support for climate change adaptation and disaster risk management at the city level 2 • Support for low-carbon solutions in the energy sector opportunity for rapidly growing cities: they can be built • The design and construction of investments better and avoid locking in costly, high-emitting and non- • Maintenance and repair climate-resilient infrastructure. -

Reclaim the Streets, the Protestival and the Creative Transformation of the City

Finisterra, XLVii, 94, 2012, pp. 103-118103 RECLAIM THE STREETS, THE PROTESTIVAL aND THE CREaTiVE TRaNSFoRMaTioN oF THE CiTY anDré carMo1 abstract – the main goal of this article is to reflect upon the relationship between creativity and urban transformation. it stems from the assumption that creativity has a para- doxical nature as it is simultaneously used for the production of the neoliberal city and by those seeking to challenge it and build alternative urban realities. first, we put forth a criti- cal review of the creative city narrative, focused on richard florida’s work, as it progres- sively became fundamental for the neoliberal city. afterwards, and contrasting with that dominant narrative, we describe a trajectory of Reclaim the Streets that provides the basis for our discussion of the protestival (protest + carnival) as its main creative force of urban transformation. Keywords: Creativity, urban transformation, Reclaim the Streets, protestival. Resumo – reclaiM the streets, o protestival e a transForMação criativa Da ciDaDe. O principal objetivo deste artigo é refletir sobre a relação existente entre criativi- dade e transformação urbana. Parte-se do princípio de que a criatividade tem uma natureza paradoxal, na medida em que é simultaneamente usada para a produção da cidade neolibe- ral, mas também por aqueles que procuram desafiá-la e construir realidades urbanas alter- nativas. Primeiro, fazemos uma revisão crítica da narrativa da cidade criativa, focada no trabalho de richard florida, por esta se ter progressivamente tornado fundamental para a cidade neoliberal. Depois, e contrastando com essa narrativa dominante, descrevemos uma trajetória do Reclaim the Streets que providencia a base para a nossa discussão do protesti- val (protesto + carnaval) como a sua principal força criativa de transformação urbana. -

Fast Policy Facts

Fast Policy Facts By Paul Dufour In collaboration with Rebecca Melville - - - As they appeared in Innovation This Week Published by RE$EARCH MONEY www.researchmoneyinc.com from January 2017 - January 2018 Table of Contents #1: January 11, 2017 The History of S&T Strategy in Canada ........................................................................................................................... 4 #2: January 18, 2017 Female Science Ministers .................................................................................................................................................... 5 #3: February 1, 2017 AG Science Reports ................................................................................................................................................................ 6 #4: February 8, 2017 The deadline approaches… ................................................................................................................................................. 7 #5: February 15, 2017 How about a couple of key moments in the history of Business-Education relations in Canada? .............. 8 #6: February 22, 2017 Our True North ........................................................................................................................................................................ 9 #7: March 8, 2017 Women in Science - The Long Road .............................................................................................................................. 11 #8: March 15, 2017 Reflecting on basic