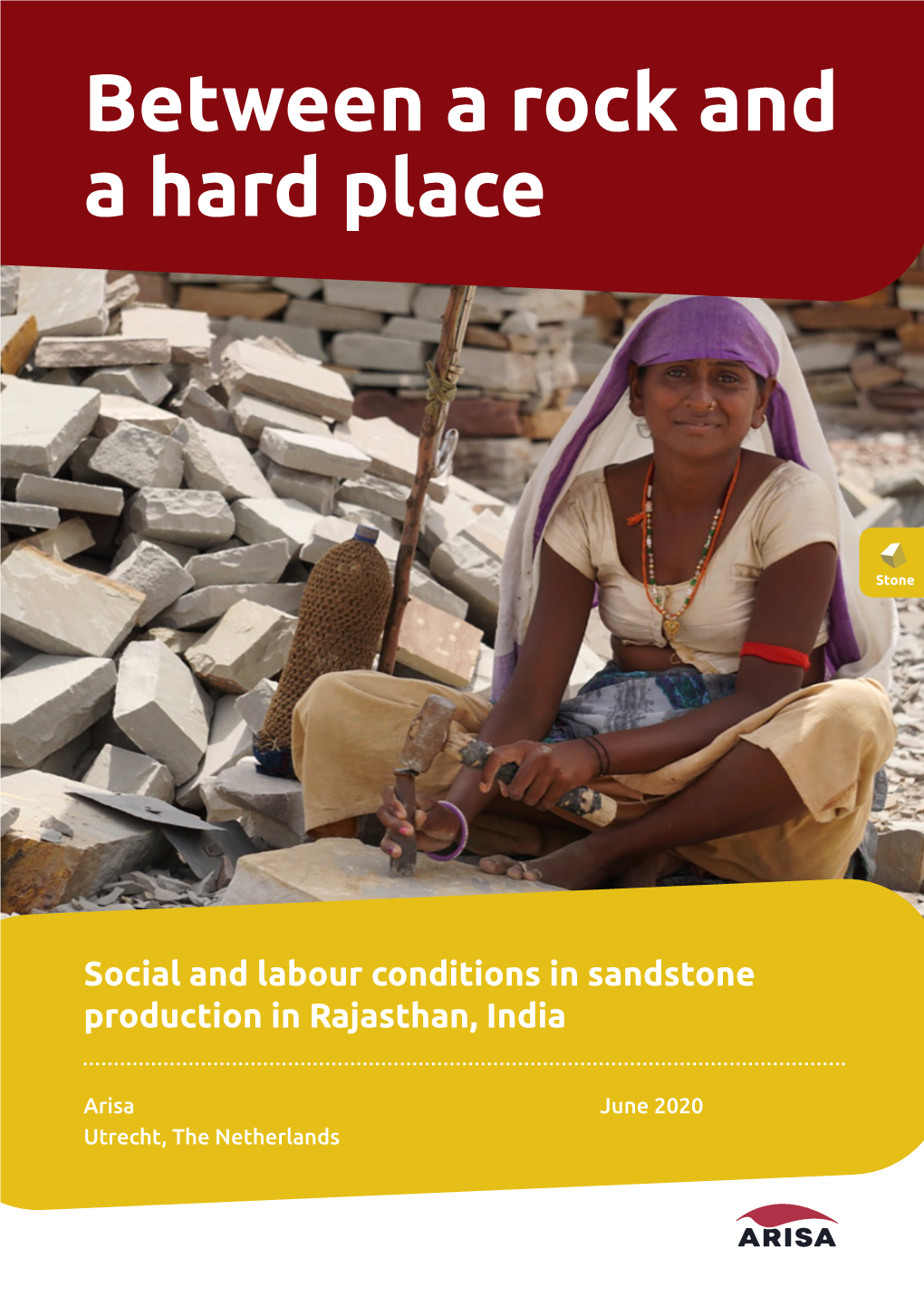

Between a Rock and a Hard Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing Smart Village Model to Achieve Objectives of Mission Antyodaya”

Guidelines For “Developing Smart Village Model to achieve objectives of Mission Antyodaya” 1. Under the Smart Village Initiative taken up by the Hon’ble Governor, every State University in Rajasthan adopted a village for developing it as a Smart Village. The objective of the ‘Smart Village’ Initiative is creation a model village, with intention to improve the quality of life of all sections of the rural people by providing basic amenities, better livelihood opportunities through skill development and higher productivity. In compliance to the direction of the Hon’ble Governor in VC Co-ordination Committee Meeting held on 21 July, 2016 in Raj Bhawan, State Universities are to adopt the second village after two- and-a half years of the adoption of first village under the “Smart Village Initiative”. Pursuant to the deliberations in the Conference of Governors held at Rashtrapati Bhawan, New Delhi on 12-13 October, 2017 and the direction of Ministry of Home Affairs, (MHA), Government of India, New Best Practices were proposed in the context of “Utkrishta Model” that defined the emerging role of Governors in New India- 2022. By successfully completing the three transitions of India’s unique development experience, viz., economic, political and Social 2017 to 2022 marks an era of making development a mass movement in India. Sankalp Se Siddhi- calls for India free from poverty, dirt and squalor, disease, corruption, terrorism and communalism by 2022, among other features. With the spirit of implementing ‘Swachha Bharat, Swastha Bharat, Shikshit Bharat, Sampann Bharat, Shaksham Bharat and Surakshit Bharat’, ingrained in Sankalp Se Siddhi, India shall emerge as a role model for the rest of the world by 2022. -

Number of Census Towns

Directorate of Census Operations, Rajasthan List of Census Towns (Census-2011) MDDS-Code Sr. No. Town Name DT Code Sub-DT Code Town Code 1 099 00458 064639 3 e Village (CT) 2 099 00459 064852 8 LLG (LALGARH) (CT) 3 099 00463 066362 3 STR (CT) 4 099 00463 066363 24 AS-C (CT) 5 099 00463 066364 8 PSD-B (CT) 6 099 00464 066641 1 GB-A (CT) 7 101 00476 069573 Kolayat (CT) 8 101 00478 069776 Beriyawali (CT) 9 103 00487 071111 Malsisar (CT) 10 103 00487 071112 Nooan (CT) 11 103 00487 071113 Islampur (CT) 12 103 00489 071463 Singhana (CT) 13 103 00490 071567 Gothra (CT) 14 103 00490 071568 Babai (CT) 15 104 00493 071949 Neemrana (CT) 16 104 00493 071950 Shahjahanpur (CT) 17 104 00496 072405 Tapookra (CT) 18 104 00497 072517 Kishangarh (CT) 19 104 00498 072695 Ramgarh (CT) 20 104 00499 072893 Bhoogar (CT) 21 104 00499 072894 Diwakari (CT) 22 104 00499 072895 Desoola (CT) 23 104 00503 073683 Govindgarh (CT) 24 105 00513 075197 Bayana ( Rural ) (CT) 25 106 00515 075562 Sarmathura (CT) 26 107 00525 077072 Sapotra (CT) 27 108 00526 077198 Mahu Kalan (CT) 28 108 00529 077533 Kasba Bonli (CT) 29 109 00534 078281 Mandawar (CT) 30 109 00534 078282 Mahwa (CT) 31 110 00540 079345 Manoharpur (CT) 32 110 00541 079460 Govindgarh (CT) 33 110 00546 080247 Bagrana (CT) 34 110 00547 080443 Akedadoongar (CT) 35 110 00548 080685 Jamwa Ramgarh (CT) Page 1 of 4 Directorate of Census Operations, Rajasthan List of Census Towns (Census-2011) MDDS-Code Sr. -

BUNDI NUMBER of VILLAGES UNDER EACH GRAM PANCHAYAT Name of Panchayat Samiti : Hindoli (0001)

Service Area Plan :: BUNDI NUMBER OF VILLAGES UNDER EACH GRAM PANCHAYAT Name of Panchayat Samiti : Hindoli (0001) Total Name of Village & Code FI Identified village (2000+ population Villages) Population Post office/sub- Location code of Name of bank with Name of Name of Service Area Bank of Post office Village branch/ Branches at the Panchayat Gram Panchayat Yes/No Panchayat Village Proposed/existing Name of allotted bank with delivery mode of Name of Village Code Person branch Banking Services i.e. BC/ATM/Branch 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 (a) 7(b) 8 9 01 PAGARA MALIYON KI 02697400 620 BRGB - HINDOLI JHOONPARIYAN HUWALYA 02697500 1,269 BRGB - HINDOLI PAGARA 02697600 924 BRGB - HINDOLI TOTAL 2,813 02 UMAR BASNI 02696600 1,808 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI BATWARI 02697200 738 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI UMAR 02697300 2,109 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORIBC BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI Yes KISHANGANJ 02699900 365 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI TOTAL 5,020 03 PECH KI BAORI DEVA KA KHERA 02696700 640 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI PAPRALA 02696800 917 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI BEEL KA KHERA 02696900 90 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI PECH KI BAORI 02697000 1,385 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI KALA MAL 02697100 690 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI BEEKARAN 02700400 178 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI MOTIPURA 02700500 473 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI BHEEMGANJ 02700600 666 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI TOTAL 5,039 04 KACHHOLA ODHANDHA 02697700 803 BRGB - HINDOLI KACHHOLA 02699600 1,883 BRGB - HINDOLI BAORI KHERA 02699700 422 BRGB - HINDOLI TOTAL 3,108 05 TONKRA TONKRA 02700700 1,663 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI TARADKYA 02700800 -

Budhpura 'Ground Zero' Sandstone Quarrying in India

Budhpura ‘Ground Zero’ Sandstone quarrying in India by P. Madhavan (Mine Labour Protection Campaign) Dr. Sanjay Raj December 2005 Study commissioned by INDIA COMMITTEE OF THE NETHERLANDS Mariaplaats 4e, 3511 LH Utrecht The Netherlands Tel. +31-30-2321340 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.indianet.nl Budhpura ‘Ground Zero’ - Sandstone quarrying in India Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................... 4 Objectives...................................................................................................................4 Methodology ...............................................................................................................4 Reading guide .............................................................................................................4 1. Value chain......................................................................................................... 5 Sandstone as a resource ..............................................................................................5 Revenue generation.....................................................................................................6 Earning foreign exchange.............................................................................................7 Supply chain, Budhpura case........................................................................................9 2. Social-economic context ................................................................................. -

Rajasthan Stone Quarries Promoting Human Rights Due Diligence and Access to Redress in Complex Supply Chains

non-judicial redress mechanisms report series 11 rajasthan stone Quarries promoting human rights due diligence and access to redress in complex supply chains Dr Shelley Marshall MonaSh UniverSity Kate taylor inDepenDent reSearcher Dr Samantha Balaton-chrimes DeaKin UniverSity About this report series this report is part of a series produced by the non-Judicial human rights redress Mechanisms project, which draws on the findings of five years of research. the findings are based on over 587 interviews, with 1,100 individuals, across the countries and case studies covered by the research. non- judicial redress mechanisms are mandated to receive complaints and mediate grievances, but are not empowered to produce legally binding adjudications. the focus of the project is on analysing the effectiveness of these mechanisms in responding to alleged human rights violations associated with transnational business activity. the series presents lessons and recommendations regarding ways that: • non-judicial mechanisms can provide redress and justice to vulnerable communities and workers • non-government organisations and worker representatives can more effectively utilise the mechanisms to provide support for and represent vulnerable communities and workers • redress mechanisms can contribute to long-term and sustainable respect and remedy of human rights by businesses throughout their operations, supply chains and other business re - lationships. the non-Judicial human rights redress Mechanisms project is an academic research collaboration between the University of Melbourne, Monash University, the University of newcastle, rMit University, Deakin University and the University of essex. the project was funded by the australian research council with support provided by a number of non-government organisations, including core coalition UK, homeWorkers Worldwide, oxfam australia and actionaid australia. -

Spermatophytic Flora of Ajmer District, Rajasthan (India)

UGC JOURNAL NUMBER 44557 International Journal of Allied Practice, Research and Review Website: www.ijaprr.com (ISSN 2350-1294) Spermatophytic Flora of Ajmer District, Rajasthan (India) R. Harsh and Poonam C. Tak Herbarium, Department of Botany, M.S. Girls College, Bikaner, Rajasthan, India Herbarium, Department of Botany, M.S. Girls College, Bikaner, Rajasthan, India Abstract-The Present paper deals with the flora of seed bearing plants of Ajmer district which is purely based on floristic exploration during the period of 2013-2015. A total number of 350 species belonging to 220 genera and 70 families are included in present paper, in which 1 from Gymnosperm and remaining 349 belongs to Angiosperm. Predominant families in this flora are Poaceae (34 species), Fabaceae (28 species), Asteraceae (23 Species), Euphorbiaceae (21 species), Caesalpiniaceae (17 species), Mimosaceae (14), Malvaceae (11 species), Convolvulaceae (11 species), Tiliaceae (11 species). Keyword: Spermatophytic Flora, Ajmer, Rajasthan. I. Introduction Proposed study area, Ajmer district is situated in the center of Rajasthan at latitude 26º27 N and longitude 74º44 E. This district is bounded by Pali district to the West, Bhilwara district to the South, Jaipur and Tonk districts to the East and Nagaur district to the North. It covers an area of 8481 km2. The climate along with the Ajmer district is subtropical. The climatic conditions are characterized by three season i.e. winter (November-February), summer (March-June) and Mansoon (July-October). II. Climatic factor Temperature- Hottest month of year − May (Minimum 26˚C, Maximum. 42˚C) Coldest month of year − January (Minimum 8˚C, Maximum 20˚C) Rainfall- Most of the rainfall occurs in the mansoon period from July-September. -

Bundi Service Area Plan of Bundi Districts Revised 1 1 of 13 Name of Panchayat Samiti : Hindoli (0001)

Service Area Plan :: BUNDI NUMBER OF VILLAGES UNDER EACH GRAM PANCHAYAT Name of Panchayat Samiti : Hindoli (0001) Total Name of Village & Code FI Identified village (2000+ population Villages) Population Post office/sub- Location code of Name of bank with Name of Name of Service Area Bank of Post office Village branch/ Branches at the Panchayat Gram Panchayat Yes/No Panchayat Village Proposed/existing Name of allotted bank with delivery mode of Name of Village Code Person branch Banking Services i.e. BC/ATM/Branch 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 (a) 7(b) 8 9 01 PAGARA MALIYON KI 02697400 620 BRGB - HINDOLI JHOONPARIYAN HUWALYA 02697500 1,269 BRGB - HINDOLI PAGARA 02697600 924 BRGB - HINDOLI TOTAL 2,813 02 UMAR BASNI 02696600 1,808 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI BATWARI 02697200 738 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI UMAR 02697300 2,109 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORIBC BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI Yes KISHANGANJ 02699900 365 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI TOTAL 5,020 03 PECH KI BAORI DEVA KA KHERA 02696700 640 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI PAPRALA 02696800 917 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI BEEL KA KHERA 02696900 90 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI PECH KI BAORI 02697000 1,385 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI KALA MAL 02697100 690 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI BEEKARAN 02700400 178 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI MOTIPURA 02700500 473 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI BHEEMGANJ 02700600 666 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI TOTAL 5,039 04 KACHHOLA ODHANDHA 02697700 803 BRGB - HINDOLI KACHHOLA 02699600 1,883 BRGB - HINDOLI BAORI KHERA 02699700 422 BRGB - HINDOLI TOTAL 3,108 05 TONKRA TONKRA 02700700 1,663 BRGB - PENCH KI BAWORI TARADKYA 02700800 -

Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited Proposes to Appoint Retail

Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in Rajasthan as per following details: Estimated Fixed Fee / monthly Type of Minimum Dimension (in M.)/Area of Finance to be arranged Mode of Security Sl. No Name of location Revenue District Type of RO Category Minimum Sales Site* the site (in Sq. M.). * by the applicant Selection Deposit Bid amount Potential # 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 SC, SC CC-1, SC CC-2, SC PH, ST, ST CC- Estimated 1, ST CC2, ST Estimated fund PH, OBC, working required for Regular / MS+HSD in OBC CC-1, capital Draw of Lots / CC / DC / CFS Frontage Depth Area development Rural Kls OBC CC-2, requirement Bidding of OBC PH, for operation infrastructur OPEN OPEN of RO e at RO CC -1 , OPEN CC -2, OPEN PH 1 Village-Lamba Hari Singh, Tehsil-Malpura TONK RURAL 85 SC CFS 35 35 1225 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 2 VILLAGE 32-F, TEHSIL SRIKARANPUR SRI GANGANAGAR RURAL 30 SC CFS 35 35 1225 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 3 SABALPUR, Tehsil -Makrana NAGAUR RURAL 90 SC CFS 35 35 1225 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 4 Village Jethliya Tehsil Peepalkhoont PRATAPGARH RURAL 156 ST CFS 35 35 1225 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 5 VILLAGE AKOLA TEHSIL BHINDER UDAIPUR RURAL 100 SC CFS 35 35 1225 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 6 Village Karanpur Tehsil-Sapotara KARAULI RURAL 40 ST CFS 35 35 1225 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 7 Between Village Dikolikala and Dabara on Kudgaon to Sapotara road KARAULI RURAL 100 ST CFS 35 35 1225 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 PAGARIA TO AWAR ROAD (BETWEEN AWAR TIRAHA & AAHU -

Final Population Totals, Series-9

Census of India 2001 Series 9 : Rajasthan FINAL POPULATION TOTALS (State, District, Tehsil and Town) c;.:n<h·lfi:I~~ IlFl)M.t()PJiN'rF.b Jayanti La. Modi Of the Indian Administrative Service Director of Census Operations, Rajasthan Jaipur Website: http://www.censusindia.net! © All rights reserved with Government of India Data Product Number O~-007-Cen-Book Preface The final population data presented in this publication is based on the processing and tabulation of actual data captured from each and every 202 million household schedules. In the past censuses the final population totals and their basic characteristics at the lowest geographical levels popularly known as the village/town Primary Census Abstract was compiled manually. Th~ generation of Primary Census Abstract for the Census 2001 is a fully computerized exercise starting from the automatic capture of data from the Household Schedule through scanning to the compilation of Primary Census Abstract. This publication titled "Final Population Totals" is only a prelude to the Primary Census Abstract. The publication, which has only one table, presents data on the total population, the Scheduled Castes population and the Scheduled Tribes population by sex at the state, district, tehsil and town levels. The village-wise data is being made available in electronic format. It is expected to be a useful ready reference document for data users who are only interested to know the basic population totals. _. This publication is brought out by Office of the Registrar General, India (ORGI) centrally. I am happy to acknowledge the dedicated efforts of Mr Jayanti Lal Modi, Director of Census Operations, Rajasthan and his team and my colleagues in the ORGI in bringing out this publication. -

Combating Child Trafficking and Bonded Labour in Rajasthan

Feasibility Study: Combating Child Trafficking and Bonded Labour in Rajasthan Submitted by Feasibility Study: Combating Child Trafficking and Bonded Labour in Rajasthan Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................... 3 List of abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 5 1. About the Study ........................................................................................................................... 10 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................ 10 1.2 Study process ......................................................................................................................... 10 1.3 Challenges and limitations ..................................................................................................... 11 2. Understanding the context in Rajasthan ....................................................................................... 13 2.1 Rajasthan: Some key demographics ....................................................................................... 13 2.2 Government of Rajasthan: Child Labour and Bonded Labour ................................................. -

Tax Payers of Bundi District Having Turnover Upto 1.5 Crore

Tax Payers of Bundi District having Turnover upto 1.5 Crore Administrative S.No GSTN_ID TRADE NAME ADDRESS Control 1 CENTRE 08ABHPJ3164C1ZY MAYUR ELECTRICALS BAKLIWALO KA NOHARA MALI PARA BUNDI, BUNDI, BUNDI, 2 STATE 08BXSPK1095H1Z0 JAI MAA DURGA STONE KARAD MANDI, VILLAGE DABI, BUNDI, BUNDI, 323022 3 STATE 08AELPJ5480J1Z2 TRUN AGENCIES MAIN ROAD, BUNDI, BUNDI, 4 STATE 08AHJPC7751J1Z3 CHITTORA AND COMPANY SUGAR MILL CHORAHA K PATAN, BUNDI, BUNDI, 5 STATE 08AUAPA4146P1ZK NAMAN TRADERS WARD NO 9 BOTTAM LEVEL, LAKHERI, BUNDI, BUNDI, 6 STATE 08AFAPG2739M1ZC GIRIRAJ TRADING CO. GANESHPURA, LAKHERI, BUNDI, BUNDI, 7 STATE 08ABBFS6543C1ZB SHRI LAXMI STONE SUTDA, BUNDI, BUNDI, 8 STATE 08ATYPB7624A1ZN SHIVAM TRADERS BEHIND AZAD PARK , BUNDI, BUNDI, 9 STATE 08ACOFS1646L1ZJ SHIVAM INFOTECH A-25, GAYATRI NAGAR, KHOJA GATE ROAD, BUNDI, BUNDI, 323001 10 STATE 08AEBPJ0057M1ZJ RATAN LAL GYAN CHAND RAMDHAN CHAURAHA, KOTA ROAD, LAKHERI, BUNDI, BUNDI, 323603 11 CENTRE 08ADOPJ8144P1ZQ RAJKAMAL AGENCIES RAJLAWATA ROAD, NEAR PETROL PUMP NAINWAN, BUNDI, BUNDI, 12 STATE 08AHFPN3967P1ZI SATYAM TRADERS SHOP NO. 10-13, KHAILAND MARKET, BUNDI, BUNDI, 323001 13 STATE 08AISPS2175A1Z2 PAWAN BEEJ BHANDAR LANKA GATE ROAD, BUNDI, BUNDI, BUNDI, 14 STATE 08ACXPG1776A1ZH NARESH BEEJ BHANDAR SHOP NO.29, NEW GRAIN MANDI, BUNDI, BUNDI, 15 STATE 08AMEPG3192P1ZM DHULICHAND AND SONS PARANA ROAD DABI, BUNDI, BUNDI, 16 STATE 08AANPO6010B1Z0 MAHESHWARI MOTORS NEAR TEHSIL ROAD HINDOLI, BUNDI, BUNDI, 17 STATE 08AHXPJ2165M1ZM SIDHARTH INDUSTRIES PLOT NO.6,I,12. RICCO INDUSRIAL AREA, -

District Census Handbook 24-Bundi, Part X a & XB, Series-18, Rajasthan

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 SERIES 18 RAJASTHAN PARTS XA & XB DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK 24. BUNDI DISTRICT V. S. VERMA O' THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERv.ce Director of Census Operations, Rajasthan The motif on the cover is a montage presenting constructions typifying the rural and urban areas. set against a background formed by specimen Census notional maps of a urban and a rural block. The drawing has been specially made for us by Shri Paras Bhansali. FOREWORD The bringing out of the District Census Handbooks is one of the various ways in which the State Govern ment collaborates with the Government of India in the work of census-taking and the dissemination of the resulting information. While the various census publications give a lot of diverse and detailed information for the bigger units of administration i.e. state, district, tehsil and town, it is left to these District Census Handbooks to present some vital data for the still lower units i.e. wards and blocks in towns and villages in tehsils. Secondly, these handbooks present some non-census data also which is collected and processed in addition to the normal census operations. The present series of District Census Handbook volumes combine parts A and B of the handbooks for each district. Part C, consisting of some other census tables at tehsil and town level as well as some other dam, wlll apFe.lf in the form of a separate series. I am gratified to note that Shri V. S. Verma, Director Census Operations, Rajasthan and his colleagues have endeavoured to bring out these exhaustive and informative volumes with precision and promptitude.