FSU ETD Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4. Non-Heptatonic Modes

Tagg: Everyday Tonality II — 4. Non‐heptatonic modes 151 4. Non‐heptatonic modes If modes containing seven different scale degrees are heptatonic, eight‐note modes are octatonic, six‐note modes hexatonic, those with five pentatonic, while four‐ and three‐note modes are tetratonic and tritonic. Now, even though the most popular pentatonic modes are sometimes called ‘gapped’ because they contain two scale steps larger than those of the ‘church’ modes of Chapter 3 —doh ré mi sol la and la doh ré mi sol, for example— they are no more incomplete FFBk04Modes2.fm. 2014-09-14,13:57 or empty than the octatonic start to example 70 can be considered cluttered or crowded.1 Ex. 70. Vigneault/Rochon (1973): Je chante pour (octatonic opening phrase) The point is that the most widespread convention for numbering scale degrees (in Europe, the Arab world, India, Java, China, etc.) is, as we’ve seen, heptatonic. So, when expressions like ‘thirdless hexatonic’ occur in this chapter it does not imply that the mode is in any sense deficient: it’s just a matter of using a quasi‐global con‐ vention to designate a particular trait of the mode. Tritonic and tetratonic Tritonic and tetratonic tunes are common in many parts of the world, not least in traditional music from Micronesia and Poly‐ nesia, as well as among the Māori, the Inuit, the Saami and Native Americans of the great plains.2 Tetratonic modes are also found in Christian psalm and response chanting (ex. 71), while the sound of children chanting tritonic taunts can still be heard in playgrounds in many parts of the world (ex. -

Tese Correções Defesa-23-7-16

! ALEXANDER SCRIABIN THE DEFINITION OF A NEW SOUND SPACE IN THE CRISIS OF TONALITY Luís Miguel Carvalhais Figueiredo Borges Coelho Tese apresentada à UniversidadeFiguiredo de Évora para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Música e Musicologia Especialidade: Musicologia ORIENTADORES: Paulo de Assis Benoît Gibson ÉVORA, JULHO DE 2016 INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO E FORMAÇÃO AVANÇADA ALEXANDER SCRIABIN THE DEFINITION OF A NEW SOUND SPACE IN THE CRISIS OF TONALITY Luís Miguel Carvalhais Figueiredo Borges Coelho Tese apresentada à Universidade de Évora para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Música e Musicologia Especialidade: Musicologia ORIENTADORES: Paulo de Assis Benoît Gibson ÉVORA, JULHO DE 2016 INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO E FORMAÇÃO AVANÇADA iii To Marta, João and Andoni, after one year of silent presence. To my parents. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my friend Paulo de Assis, for all his dedication and encouragement in supervising my research. His enthusiasm, knowledge and always-challenging opinions were a permanent stimulus to look further. I thank Benoît Gibson for having accepted to co-supervise my work, despite my previous lack of any musicological experience. I extend my gratitude to Stanley Hanks, whose willingness to supervise my English was only limited by the small number of pages I could submit to his advice before the inexorable deadline. Thanks are also due to my former piano teachers—Amélia Vilar, Isabel Rocha, Vitaly Margulis, Dimitri Bashkirov and Galina Egyazarova—for having taught me everything I know about music. To my dear friends Catarina and André I will be always grateful: without their indefatigable assistance in the final assembling of this dissertation, my erratic relation with the writing software would have surely slipped into chaos. -

Music%2034.Syllabus

Music 34, Detailed Syllabus INTRODUCTION—January 24 (M) “Half-step over-saturation”—Richard Strauss Music: Salome (scene 1), Morgan 9 Additional reading: Richard Taruskin, The Oxford History of Western Music, vol. 4 (henceforth RT), (see Reader) 36-48 Musical vocabulary: Tristan progression, augmented chords, 9th chords, semitonal expansion/contraction, master array Recommended listening: more of Salome Recommended reading: Derrick Puffett, Richard Strauss Salome. Cambridge Opera Handbooks (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989) No sections in first week UNIT 1—Jan. 26 (W); Jan. 31 (M) “Half-steplessness”—Debussy Music: Estampes, No. 2 (La Soiré dans Grenade), Morgan 1; “Nuages” from Three Nocturnes (Anthology), “Voiles” from Preludes I (Anthology) Reading: RT 69-83 Musical vocabulary: whole-tone scales, pentatonic scales, parallelism, whole-tone chord, pentatonic chords, center of gravity/symmetry Recommended listening: Three Noctures SECTIONS start UNIT 2—Feb. 2 (W); Feb. 7 (M) “Invariance”—Skryabin Music: Prelude, Op. 35, No. 3; Etude, Op. 56, No. 4, Prelude Op. 74, No. 3, Morgan 21-25. Reading: RT 197-227 Vocabulary: French6; altered chords; Skryabin6; tritone link; “Ecstasy chord,” “Mystic chord”, octatonicism (I) Recommended reading: Taruskin, “Scriabin and the Superhuman,” in Defining Russia Musically: Historical and Hermeneutical Essays (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 308-359 Recommended listening: Poème d’extase; Alexander Krein, Sonata for Piano UNIT 3—Feb. 9 (W); Feb. 14 (M) “Grundgestalt”—Schoenberg I Music: Opus 16, No. 1, No. 5, Morgan 30-45. Reading: RT 321-337, 341-343; Simms: The Atonal Music of Arnold Schoenberg 1908-1923 (excerpt) Vocabulary: atonal triads, set theory, Grundgestalt, “Aschbeg” set, organicism, Klangfarben melodie Recommended reading: Móricz, “Anxiety, Abstraction, and Schoenberg’s Gestures of Fear,” in Essays in Honor of László Somfai on His 70th Birthday: Studies in the Sources and the Interpretation of Music, ed. -

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE the Gypsy Violin A

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE The Gypsy Violin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Music in Music, Performance By Eun Ah Choi December 2019 The thesis of Eun Ah Choi is approved: ___________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Liviu Marinesqu Date ___________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Ming Tsu Date ___________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Lorenz Gamma, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Table of Contents Signature Page…………………………………………………………………………………….ii List of Examples……………………………………………………………………………...…..iv Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………....v Chapter 1: Introduction.……………..……………………………………………………….……1 Chapter 2: The Establishment of the Gypsy Violin.……………………….……………………...3 Chapter 3: Bela Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances [1915].………….…….……………………….8 Chapter 4: Vittorio Monti’s Csádás [1904]….…………………………………..………………18 Chapter 5: Conclusion …………..……………...……………………………………………….24 Works Cited.…………….……………………………………………………………………….26 California State University, Northridge iii List of Examples 1 Bartók’s Romanian Dances, Movement I: mm. 1-13……………………………………..9 2 Bartók’s Romanian Dances, Movement II: mm. 1-16…………………………...………10 3 Bartók’s Romanian Dances, Movement III …………………………………..…………12 4 Bartók’s Romanian Dances, Movement IV …………………………………..…………14 5 Bartók’s Romanian Dances, Movement V: mm. 5-16…………………………………...16 6 Monti’s Csárdás, m. 5………………………………………………..………………......19 7 Monti’s Csardas, mm. 6-9…………………………………………..…………………...19 8 Monti’s Csárdás, mm. 14-16.…………………………………….……………………...20 9 Monti’s Csárdás, mm. 20-21.………………………………….……………………..….20 10 Monti’s Csárdás, mm. 22-37………………….…………………………………………21 11 Monti’s Csárdás, mm. 38-53…………………….………………………………………22 12 Monti’s Csárdás, mm. 70-85…………………….………………………………………23 iv Abstract The Gypsy violin By Eun Ah Choi Master of Music in Music, Performance The origins of the Gypsies are not exactly known, and they lived a nomadic lifestyle for centuries, embracing many cultures, including music. -

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors Richard Bass Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 38, No. 2. (Autumn, 1994), pp. 155-186. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-2909%28199423%2938%3A2%3C155%3AMOOAWI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-X Journal of Music Theory is currently published by Yale University Department of Music. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/yudm.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mon Jul 30 09:19:06 2007 MODELS OF OCTATONIC AND WHOLE-TONE INTERACTION: GEORGE CRUMB AND HIS PREDECESSORS Richard Bass A bifurcated view of pitch structure in early twentieth-century music has become more explicit in recent analytic writings. -

A Pedagogical Analysis and Performance of Selected Compositions for Piano by Vincent Persichetti

A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE OF SELECTED COMPOSITIONS FOR PIANO BY VINCENT PERSICHETTI By Copyright 2016 Chi Kit Lam Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Jack Winerock ________________________________ Dr. Scott McBride Smith ________________________________ Dr. Michael Kirkendoll ________________________________ Prof. Scott Murphy ________________________________ Dr. Alfred Tat-Kei Ho Date defended: May 11, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Chi Kit Lam certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE OF SELECTED COMPOSITIONS FOR PIANO BY VINCENT PERSICHETTI ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Jack Winerock Date approved: May 11, 2016 ii ABSTRACT Vincent Persichetti composed in a wide range of contemporary musical idioms. He incorporated twentieth-century harmonies into traditional forms and into classical piano writing. This paper seeks to emphasize the advantages of his music for piano pedagogy. Chapter Two concentrates on the composer’s life, compositional style, contribution and rewards, and it includes a short list of piano compositions. Chapter Three examines and analyzes four selected pieces by Persichetti: Little Piano Book, Piano Sonata No. 9, Poems for Piano No. 2 “Soft is the Collied Night,” and Four Arabesques, Op. 141, No. 1 Affabile. The Poem, the Arabesque, and the miniatures in Little Piano Book are smaller pieces, intended for amateur and intermediate pianists. The Ninth Sonata is a more substantial composition for advanced pianists. These pieces provide a broad image of Persichetti’s piano compositions. This study of selected works by Persichetti shows that his music is excellent pedagogical material for piano students as well as outstanding music to be performed in the concert hall. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 © Copyright by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age by Ryan Isao Rowen Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Mitchell Bryan Morris, Chair The Silver Age has long been considered one of the most vibrant artistic movements in Russian history. Due to sweeping changes that were occurring across Russia, culminating in the 1917 Revolution, the apocalyptic sentiments of the general populace caused many intellectuals and artists to turn towards esotericism and occult thought. With this, there was an increased interest in transcendentalism, and art was becoming much more abstract. The tenets of the Russian Symbolist movement epitomized this trend. Poets and philosophers, such as Vladimir Solovyov, Andrei Bely, and Vyacheslav Ivanov, theorized about the spiritual aspects of words and music. It was music, however, that was singled out as possessing transcendental properties. In recent decades, there has been a surge in scholarly work devoted to the transcendent strain in Russian Symbolism. The end of the Cold War has brought renewed interest in trying to understand such an enigmatic period in Russian culture. While much scholarship has been ii devoted to Symbolist poetry, there has been surprisingly very little work devoted to understanding how the soundscape of music works within the sphere of Symbolism. -

Andrián Pertout

Andrián Pertout Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition Volume 1 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Produced on acid-free paper Faculty of Music The University of Melbourne March, 2007 Abstract Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition encompasses the work undertaken by Lou Harrison (widely regarded as one of America’s most influential and original composers) with regards to just intonation, and tuning and scale systems from around the globe – also taking into account the influential work of Alain Daniélou (Introduction to the Study of Musical Scales), Harry Partch (Genesis of a Music), and Ben Johnston (Scalar Order as a Compositional Resource). The essence of the project being to reveal the compositional applications of a selection of Persian, Indonesian, and Japanese musical scales utilized in three very distinct systems: theory versus performance practice and the ‘Scale of Fifths’, or cyclic division of the octave; the equally-tempered division of the octave; and the ‘Scale of Proportions’, or harmonic division of the octave championed by Harrison, among others – outlining their theoretical and aesthetic rationale, as well as their historical foundations. The project begins with the creation of three new microtonal works tailored to address some of the compositional issues of each system, and ending with an articulated exposition; obtained via the investigation of written sources, disclosure -

Constellations Persichetti @ 100 and Music From

2015/16 Season: Constellations Persichetti @ 100 and Music from the Generation He Inspired 31ST SEASON 17 & 18 October, 2015 Curtis Institute of Music Philadelphia, PA Introduction: Vincent Persichetti @ 100 Vincent Persichetti was one of the most widely respected musicians of his generation. A prolific composer, brilliant educator and lecturer, and prodigious pianist, he composed more than 150 works in virtu- ally all genres and for virtually all performing media, while serving for 40 years on the faculty of the Juilliard School, many of them as chairman of the composition department. During his lifetime Persichetti influenced the musical lives of thou- sands of people from all walks of life, and his name came to signify a comprehensive musicianship virtually unparalleled among American composers. Countless young pianists were nurtured on his sonatinas and the Little Piano Book, while many other young instrumental students first experienced serious contemporary music through his works for band; church choirs turned to his Hymns and Respons- es for the Church Year as an inexhaustible resource, while many young composers have found his classic textbook Twentieth Century Harmony to be an indispensable tool; among professional soloists and conductors his sonatas, concertos, and symphonies stood among the masterworks of American music. Throughout his life Persichetti encouraged healthy, creative participation in music at all levels of proficiency, while shunning dogmas that advocated one composition- al approach at the expense of others. He was beloved and admired as a teacher, and was in great demand as a lecturer, using his comprehensive knowledge of the repertoire, extraordinary gift for improvisation, awe-inspiring piano technique, and mischievous wit to captivate audiences. -

Download Music Theory IV Syllabus 2018

MUSC 212 Prof. Tim Tollefson Music Theory IV Office: YFAC 206 Spring, 2018 [email protected] MWF 10:30-11:20 AM Office Phone: 382 Course Description This is the final course in a series (MUSC 111, 112, 211, and 212) that is designed to give the student a firm grasp of the concepts and practices commonly found in Western art music. Music of the 19th and 20th centuries will be the primary focus. Contemporary music (late 20th century and early 21st century) will also be discussed, although not in as much detail. The initial focus will be on the increased use of chromaticism and enharmonic chords, and then later we will study some of the new methods of music composition that came to the fore when the traditional tonal system broke down. This course supports the music department's overall objective for music theory, composition and music skills, which reads as follows: Students will be able to create, manipulate and analyze musical structures typical of the major historical periods, utilizing the many elements of musical language such as melody, harmony, rhythm, form, timbre, and notation. (Program Learning Outcome 1) Learning Outcomes for Music Theory IV: A student who gets an “A” in this course will be able to: --explain the numerous musical terms covered in the course --do a Roman numeral analysis of musical compositions involving the various types of chords covered in Music Theory I-IV --label embellishing tones in a tonal composition --recognize, create and use doubly augmented 4th chords, enharmonic diminished 7ths, enharmonic German -

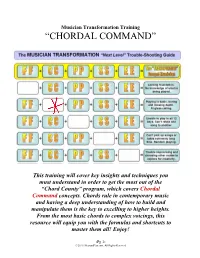

“Chordal Command”

Musician Transformation Training “CHORDAL COMMAND” This training will cover key insights and techniques you must understand in order to get the most out of the “Chord County” program, which covers Chordal Command concepts. Chords rule in contemporary music and having a deep understanding of how to build and manipulate them is the key to excelling to higher heights. From the most basic chords to complex voicings, this resource will equip you with the formulas and shortcuts to master them all! Enjoy! -Pg 1- © 2010. HearandPlay.com. All Rights Reserved Introduction In this guide, we’ll be starting with triads and what I call the “FANTASTIC FOUR.” Then we’ll move on to shortcuts that will help you master extended chords (the heart of contemporary playing). After that, we’ll discuss inversions (the key to multiplying your chordal vocaluary), primary vs secondary chords, and we’ll end on voicings and the difference between “voicings” and “inversions.” But first, let’s turn to some common problems musicians encounter when it comes to chordal mastery. Common Problems 1. Lack of chordal knowledge beyond triads: Musicians who fall into this category simply have never reached outside of the basic triads (major, minor, diminished, augmented) and are stuck playing the same chords they’ve always played. There is a mental block that almost prohibits them from learning and retaining new chords. Extra effort must be made to embrace new chords, no matter how difficult and unusual they are at first. Knowing the chord formulas and shortcuts that will turn any basic triad into an extended chord is the secret. -

Studies in Instrumentation and Orchestration and in the Recontextualisation of Diatonic Pitch Materials (Portfolio of Compositions)

Studies in Instrumentation and Orchestration and in the Recontextualisation of Diatonic Pitch Materials (Portfolio of Compositions) by Chris Paul Harman Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music School of Humanities The University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract: The present document examines eight musical works for various instruments and ensembles, composed between 2007 and 2011. Brief summaries of each work’s program are followed by discussions of instrumentation and orchestration, and analysis of pitch organization. Discussions of instrumentation and orchestration explore the composer’s approach to diversification of instrumental ensembles by the inclusion of non-orchestral instruments, and redefinition of traditional hierarchies among instruments in a standard ensemble or orchestral setting. Analyses of pitch organization detail various ways in which the composer renders diatonic