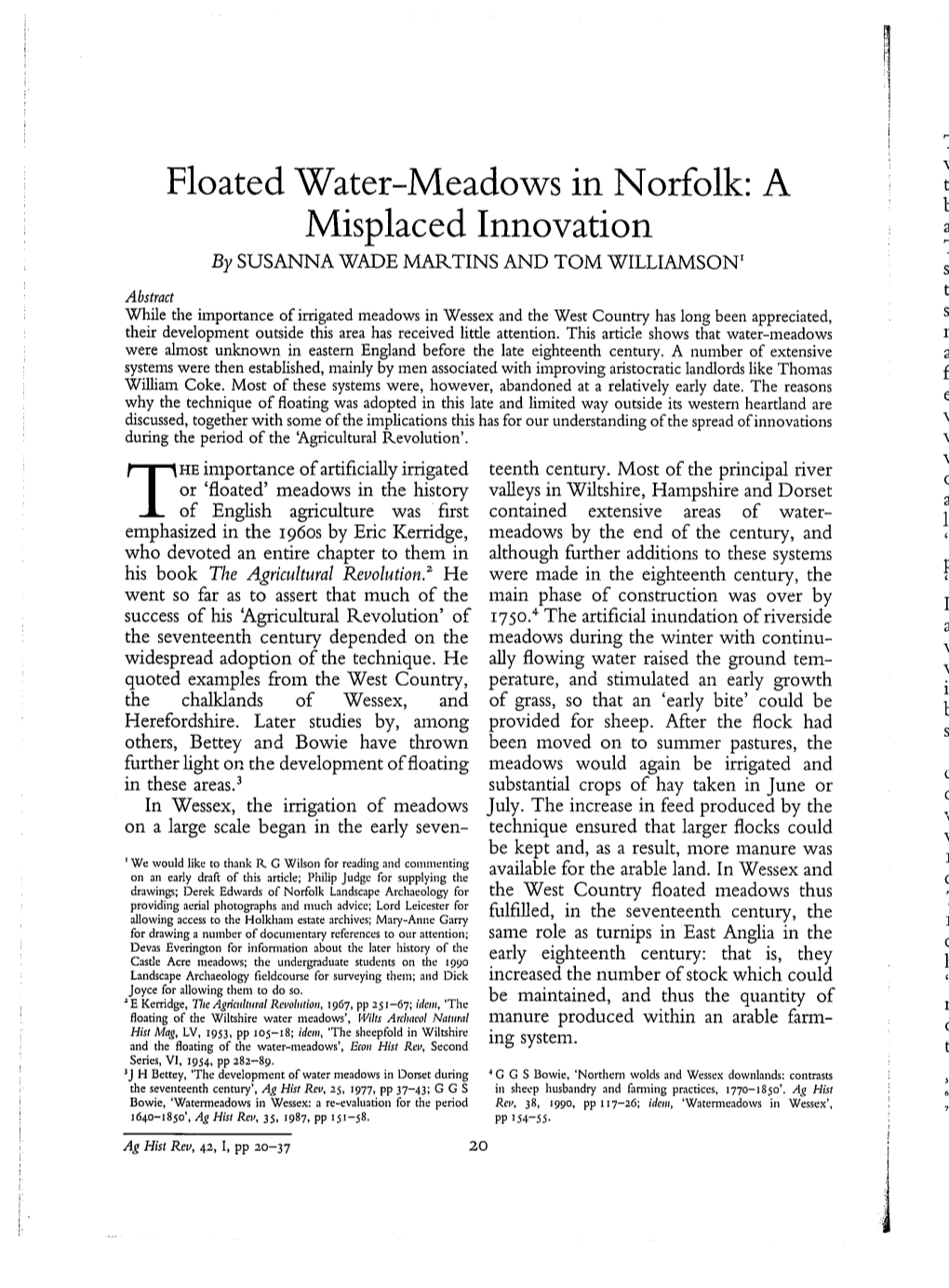

Floated Water-Meadows in Norfolk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council Tax Rates 2020 - 2021

BRECKLAND COUNCIL NOTICE OF SETTING OF COUNCIL TAX Notice is hereby given that on the twenty seventh day of February 2020 Breckland Council, in accordance with Section 30 of the Local Government Finance Act 1992, approved and duly set for the financial year beginning 1st April 2020 and ending on 31st March 2021 the amounts as set out below as the amount of Council Tax for each category of dwelling in the parts of its area listed below. The amounts below for each parish will be the Council Tax payable for the forthcoming year. COUNCIL TAX RATES 2020 - 2021 A B C D E F G H A B C D E F G H NORFOLK COUNTY 944.34 1101.73 1259.12 1416.51 1731.29 2046.07 2360.85 2833.02 KENNINGHALL 1194.35 1393.40 1592.46 1791.52 2189.63 2587.75 2985.86 3583.04 NORFOLK POLICE & LEXHAM 1182.24 1379.28 1576.32 1773.36 2167.44 2561.52 2955.60 3546.72 175.38 204.61 233.84 263.07 321.53 379.99 438.45 526.14 CRIME COMMISSIONER BRECKLAND 62.52 72.94 83.36 93.78 114.62 135.46 156.30 187.56 LITCHAM 1214.50 1416.91 1619.33 1821.75 2226.58 2631.41 3036.25 3643.49 LONGHAM 1229.13 1433.99 1638.84 1843.70 2253.41 2663.12 3072.83 3687.40 ASHILL 1212.28 1414.33 1616.37 1818.42 2222.51 2626.61 3030.70 3636.84 LOPHAM NORTH 1192.57 1391.33 1590.09 1788.85 2186.37 2583.90 2981.42 3577.70 ATTLEBOROUGH 1284.23 1498.27 1712.31 1926.35 2354.42 2782.50 3210.58 3852.69 LOPHAM SOUTH 1197.11 1396.63 1596.15 1795.67 2194.71 2593.74 2992.78 3591.34 BANHAM 1204.41 1405.14 1605.87 1806.61 2208.08 2609.55 3011.01 3613.22 LYNFORD 1182.24 1379.28 1576.32 1773.36 2167.44 2561.52 2955.60 3546.72 -

Norfolk Through a Lens

NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service 2 NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service History and Background The systematic collecting of photographs of Norfolk really began in 1913 when the Norfolk Photographic Survey was formed, although there are many images in the collection which date from shortly after the invention of photography (during the 1840s) and a great deal which are late Victorian. In less than one year over a thousand photographs were deposited in Norwich Library and by the mid- 1990s the collection had expanded to 30,000 prints and a similar number of negatives. The devastating Norwich library fire of 1994 destroyed around 15,000 Norwich prints, some of which were early images. Fortunately, many of the most important images were copied before the fire and those copies have since been purchased and returned to the library holdings. In 1999 a very successful public appeal was launched to replace parts of the lost archive and expand the collection. Today the collection (which was based upon the survey) contains a huge variety of material from amateur and informal work to commercial pictures. This includes newspaper reportage, portraiture, building and landscape surveys, tourism and advertising. There is work by the pioneers of photography in the region; there are collections by talented and dedicated amateurs as well as professional art photographers and early female practitioners such as Olive Edis, Viola Grimes and Edith Flowerdew. More recent images of Norfolk life are now beginning to filter in, such as a village survey of Ashwellthorpe by Richard Tilbrook from 1977, groups of Norwich punks and Norfolk fairs from the 1980s by Paul Harley and re-development images post 1990s. -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 20.3 Socc Stakeholder Mailing List

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 20.3 SoCC Stakeholder Mailing List Applicant: Norfolk Vanguard Limited Document Reference: 5.1 Pursuant to APFP Regulation: 5(2)(q) Date: June 2018 Revision: Version 1 Author: BECG Photo: Kentish Flats Offshore Wind Farm This page is intentionally blank. Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Appendices Parish Councils Bacton and Edingthorpe Parish Council Witton and Ridlington Parish Council Brandiston Parish Council Guestwick Parish Council Little Witchingham Parish Council Marsham Parish Council Twyford Parish Council Lexham Parish Council Yaxham Parish Council Whinburgh and Westfield Parish Council Holme Hale Parish Council Bintree Parish Council North Tuddenham Parish Council Colkirk Parish Council Sporle with Palgrave Parish Council Shipdham Parish Council Bradenham Parish Council Paston Parish Council Worstead Parish Council Swanton Abbott Parish Council Alby with Thwaite Parish Council Skeyton Parish Council Melton Constable Parish Council Thurning Parish Council Pudding Norton Parish Council East Ruston Parish Council Hanworth Parish Council Briston Parish Council Kempstone Parish Council Brisley Parish Council Ingworth Parish Council Westwick Parish Council Stibbard Parish Council Themelthorpe Parish Council Burgh and Tuttington Parish Council Blickling Parish Council Oulton Parish Council Wood Dalling Parish Council Salle Parish Council Booton Parish Council Great Witchingham Parish Council Aylsham Town Council Heydon Parish Council Foulsham Parish Council Reepham -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries. -

Norfolk Strategic Planning Framework

Norfolk Strategic Planning Framework Shared Spatial Objectives for a Growing County and Statement of Common Ground May 2021 Signatories • Breckland District Council • Broadland District Council • Broads Authority • Great Yarmouth Borough Council • Borough Council of King’s Lynn and West Norfolk • North Norfolk District Council • Norwich City Council • South Norfolk Council • Norfolk County Council • Natural England • Environment Agency • Anglian Water • Marine Management Organisation • New Anglia Local Enterprise Partnership • Active Norfolk • Water Resources East Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the following organisations for their support in the production of this document: • Breckland District Council • Broadland District Council • Broads Authority • Great Yarmouth Borough Council • Borough Council of King’s Lynn and West Norfolk • North Norfolk District Council • Norwich City Council • South Norfolk Council • Norfolk County Council • Suffolk County Council • Babergh & Mid Suffolk District Councils • East Suffolk Council • West Suffolk Council • Fenland District Council • East Cambridgeshire District Council • South Holland District Council • Natural England • Environment Agency • Wild Anglia • Anglian Water • New Anglia Local Enterprise Partnership • UK Power Networks • Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Combined Authority • Norfolk and Waveney CCG • NHS Sustainability and Transformation Partnership Estates for Norfolk and Waveney • Mobile UK Norfolk Strategic Planning Framework Page 2 Contents SIGNATORIES ........................................................................................................................ -

2017 14Th March

HOLME-NEXT-THE-SEA PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of a Meeting of the Parish Council in the Village Hall, Kirkgate, on Tuesday 14th March at 7 pm Present: Kevin Felgate (Chairman) Gillian Morley Lynn Devereux Martin Crown In Attendance: Christina Jones (Temporary Clerk) There were 8 members of the public present. Councillor Felgate welcomed everyone and thanked them for their attendance. 1. Apologies for Absence and approval of reasons for absence. Apologies had been received from Councillor Burton (family commitment), Councillor Easton (illness) and Councillor Needham (illness). 2. Declarations of Interest. Councillor Crown declared an interest in Item 11(c) as he is a member of the Parochial Church Council. 3. Confirmation of Minutes. It was RESOLVED (unanimously) that the Minutes of the Meeting held on 14th February 2017 be confirmed as a true record and signed by the Chairman after the following amendment: Page 459 - The tenth line from the bottom should read .....'although there are currently some compensation schemes in place which may provide similar habitat on an alternative site.' 4. Matters arising (information only). Councillor Devereux raised a number of issues from the Minutes of the meeting held on 14th February 2017 which were not Agenda items: Item 5 - Policy and Partnership Officer, Norfolk Coast Partnership (NCP). (i) With regard to the water samples mentioned in this report, these are necessary to establish that the marsh is not being flooded with polluted water. Some funding has now been offered for this work. (ii) The Clerk was requested to ask Robin Jolliffe to report back to the Parish Council on any NCP meetings with the Norfolk Wildlife Trust (NWT) and/or the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) that he attends as a parishioner volunteer. -

Planning Committee – 9 September 2020 Applications

PLANNING COMMITTEE – 9 SEPTEMBER 2020 APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform Members of those applications which have been determined under the officer delegation scheme since your last meeting. These decisions are made in accordance with the Authority’s powers contained in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and have no financial implications. RECOMMENDATION That the report be noted. DETAILS OF DECISIONS DATE DATE REF NUMBER APPLICANT PARISH/AREA RECEIVED DETERMINED/ PROPOSED DEV DECISION 15.06.2020 18.08.2020 20/00051/TPO Cottontail Lodge 11 Bagthorpe Bagthorpe With Barmer - TPO Work Road Bircham Newton Norfolk VACANT Approved 2/TPO/00544: T1 - Oak - Reduce to about an 8m radius of the growth towards the house and over the hedge line, raise the canopy to about 5m all round, crown clean to include deadwood etc. Lowest branch to be removed and T2 - Oak - to reduce the growth overhanging the property to about 10m radius, slight reduction too of the growth growing towards No.11 )opposite), crown clean and raise to about 5m 04.06.2020 06.08.2020 20/00824/F 4 Manor Farm Barns Main Road Brancaster Application Brancaster Norfolk Permitted Addition of rooflight to main dwelling. Conversion of carport to gym/hobby room. Extension of gazebo to connect to dwelling and erection of a garden wall 11.08.2020 21.08.2020 20/00076/TPO Tolls Close Cross Lane Brancaster Brancaster Tree Application King's Lynn - No objection 2/TPO/00249 and in a Conservation Area: T1- Cedar crown lift, T2 - Cedar reduce top, T3 - Macrocappa -

CPRE Norfolk Housing Allocation Pledge Signatures – Correct As of 24 March 2021 South Norfolk Alburgh Ashby St Mary Barford &A

CPRE Norfolk Housing Allocation Pledge Signatures – correct as of 24 March 2021 South Norfolk Alburgh Ashby St Mary Barford & Wramplingham Barnham Broom Bawburgh Bergh Apton Bracon Ash and Hethel Brockdish Broome Colney Costessey Cringleford Dickleburgh and Rushall Diss Framingham Pigot Forncett Gissing Great Melton Hempnall Hethersett Hingham Keswick and Intwood Kirby Cane and Ellingham Langley with Hardley Marlingford and Colton Mulbarton Rockland St Mary with Hellington Saxlingham Nethergate Scole Shelfanger Shelton and Hardwick Shotesham Stockton Surlingham Thurlton Thurton Thwaite St Mary Tivetshall St Margaret Tivetshall St Mary Trowse with Newton Winfarthing Wreningham Broadland Acle Attlebridge Beighton Blofield Brandiston Buxton with Lamas Cantley, Limpenhoe and Southwood Coltishall Drayton Felthorpe Frettenham Great Witchingham Hainford Hemblington Hevingham Honingham Horsford Horsham St Faiths Lingwood and Burlingham Reedham Reepham Ringland Salhouse Stratton Strawless Strumpshaw Swannington with Alderford and Little Witchingham Upton with Fishley Weston Longville Wood Dalling Woodbastwick Total = 72 Total parishes in Broadland & South Norfolk = 181 % signed = 39.8% Breckland Ashill Banham Bintree Carbrooke Caston Colkirk Cranworth East Tuddenham Foulden Garveston, Reymerston & Thuxton Gooderstone Great Ellingham Harling Hockering Lyng Merton Mundford North Tuddenham Ovington Rocklands Roudham & Larling Saham Toney Scoulton Stow Bedon & Breckles Swaffham Weeting with Broomhill Whinburgh & Westfield Wretham Yaxham Great Yarmouth -

830-182 Castle Acre Conservation Area.Indd

Castle Acre Conservation Area Character Statement CASTLE ACRE, 4 miles N. of Swaffham, and 14 miles E. by S. of Lynn, is a considerable village, of great antiquity, having some traces of a Roman station, and the remains of an immense Castle and extensive Priory. WILLIAM WHITE 1845 Character Statement Designated: April 1971 Revised May 2009 Castle Acre Conservation Area Region Introduction 1 Origins and Historical Development 1 Setting and Location 4 Character Overview 4 Spaces and Buildings 5 Listed Buildings 8 Important Unlisted Buildings 11 Post War Development 11 Traditional Materials 11 Archaeological Interest 12 Detractors 12 Conservation Objectives 13 [email protected] Character Statement www.west-norfolk.gov.uk Castle Acre Conservation Area Introduction where changes to the environment occur, they do so in a sympathetic way without .0.1 A Conservation Area - “An area of harm to the essential character of the area. special architectural or historic interest, This type of assessment has been the character or appearance of which it encouraged by Government Advice (PPG15) is desirable to preserve or enhance”. and it has been adopted as supplementary planning guidance. .0.2 The conservation of the historic environment is part of our quality of life, .0.5 This character statement does not helping to foster economic prosperity and address enhancement proposals. providing an attractive environment in which Community led enhancement schemes will to live or work. The Borough Council is be considered as part of a separate process. committed to the protection and enhancement of West Norfolk’s historic built Origins and Historical environment and significant parts of it are Development designated as conservation areas. -

NORFOLK. SMI 793 Dyball Alfred, West Raynham, Faken- Hales William Geo

TRADES DIRECTORY. J NORFOLK. SMI 793 Dyball Alfred, West Raynham, Faken- Hales William Geo. Ingham, Norwich Kitteringham John, Tilney St. Law- ham Hall P. Itteringham, Aylsham R.S.O rence, Lynn Dyball E. T. 24 Fuller's hill, Yarmouth Hammond F. Barroway Drove, Downhm Knights Edwd. H. London rd. Harleston Dye Henry Samuel, 39 Audley street & Hammond Richard, West Bilney, Lynn Knott Charles, Ten Mile Bank, Downhm North Market road, Yarmouth & at Pentney, Swaffham Kybird J ames, Croxton, Thetford Earl Uriah, Coltishall, Norwich Hammond Robert Edward Hazel, Lade Frederick Wacton, Long Stratton Easter Frederick, Mileham, Swaffham Gayton, Lynn Lake Thomas, Binham, Wighton R.S.O Easter George, Blofield, Norwich Hammond William, Stow Bridge, Stow Lambert William Claydon, Wiggenhall Ebbs William, Alburgh, Harleston Bardolph, Downham St. Mary Magdalen, Lynn Edward Alfred, Griston, Thetford Hanton J ames, W estEnd street, Norwich Langham Alfred, Martham, Yarmouth Edwards Edward, Wretham, Great Harbord P. Burgh St. Margaret, Yarmth Lansdell Brothers, Hempnall, Norwich Hockham, Thetford Hardy Harry, Lake's end, Wisbech Lansdell Albert, Stratton St. Mary, Eggleton W. Great Ryburgh, Fakenham Harper Robt. Alfd. Halvergate, Nrwch Long Stratton R.S.O Eglington & Gooch, Hackford, Norwich Harrold Samuel, Church end, West Larner Henry, Stoke Ferry ~.0 Eke Everett, Mulbarton, Norwich Walton, Wisbech Last F. B. 93 Sth. Market rd. Yarmouth Eke Everet, Bracon Ash, Norwich Harrowven Henry, Catton, Norwich Lawes Harry Wm. Cawshm, Norwich Eke James, Saham Ton.ey, Thetford Hawes A. Terrington St. John, Wisbech Laws .Jo~eph, Spixworth, Norwich Eke R. Drayton, Norwich Hawes Robert Hilton, Terrington St. Leader James, Po!'ltwick, Norwich Ellis Charles, Palling, Norwich Clement, Lynn Leak T. -

Areas Designated As 'Rural' for Right to Buy Purposes

Areas designated as 'Rural' for right to buy purposes Region District Designated areas Date designated East Rutland the parishes of Ashwell, Ayston, Barleythorpe, Barrow, 17 March Midlands Barrowden, Beaumont Chase, Belton, Bisbrooke, Braunston, 2004 Brooke, Burley, Caldecott, Clipsham, Cottesmore, Edith SI 2004/418 Weston, Egleton, Empingham, Essendine, Exton, Glaston, Great Casterton, Greetham, Gunthorpe, Hambelton, Horn, Ketton, Langham, Leighfield, Little Casterton, Lyddington, Lyndon, Manton, Market Overton, Martinsthorpe, Morcott, Normanton, North Luffenham, Pickworth, Pilton, Preston, Ridlington, Ryhall, Seaton, South Luffenham, Stoke Dry, Stretton, Teigh, Thistleton, Thorpe by Water, Tickencote, Tinwell, Tixover, Wardley, Whissendine, Whitwell, Wing. East of North Norfolk the whole district, with the exception of the parishes of 15 February England Cromer, Fakenham, Holt, North Walsham and Sheringham 1982 SI 1982/21 East of Kings Lynn and the parishes of Anmer, Bagthorpe with Barmer, Barton 17 March England West Norfolk Bendish, Barwick, Bawsey, Bircham, Boughton, Brancaster, 2004 Burnham Market, Burnham Norton, Burnham Overy, SI 2004/418 Burnham Thorpe, Castle Acre, Castle Rising, Choseley, Clenchwarton, Congham, Crimplesham, Denver, Docking, Downham West, East Rudham, East Walton, East Winch, Emneth, Feltwell, Fincham, Flitcham cum Appleton, Fordham, Fring, Gayton, Great Massingham, Grimston, Harpley, Hilgay, Hillington, Hockwold-Cum-Wilton, Holme- Next-The-Sea, Houghton, Ingoldisthorpe, Leziate, Little Massingham, Marham, Marshland