Point Four: a Re-Examination of Ends and Means

Total Page:16

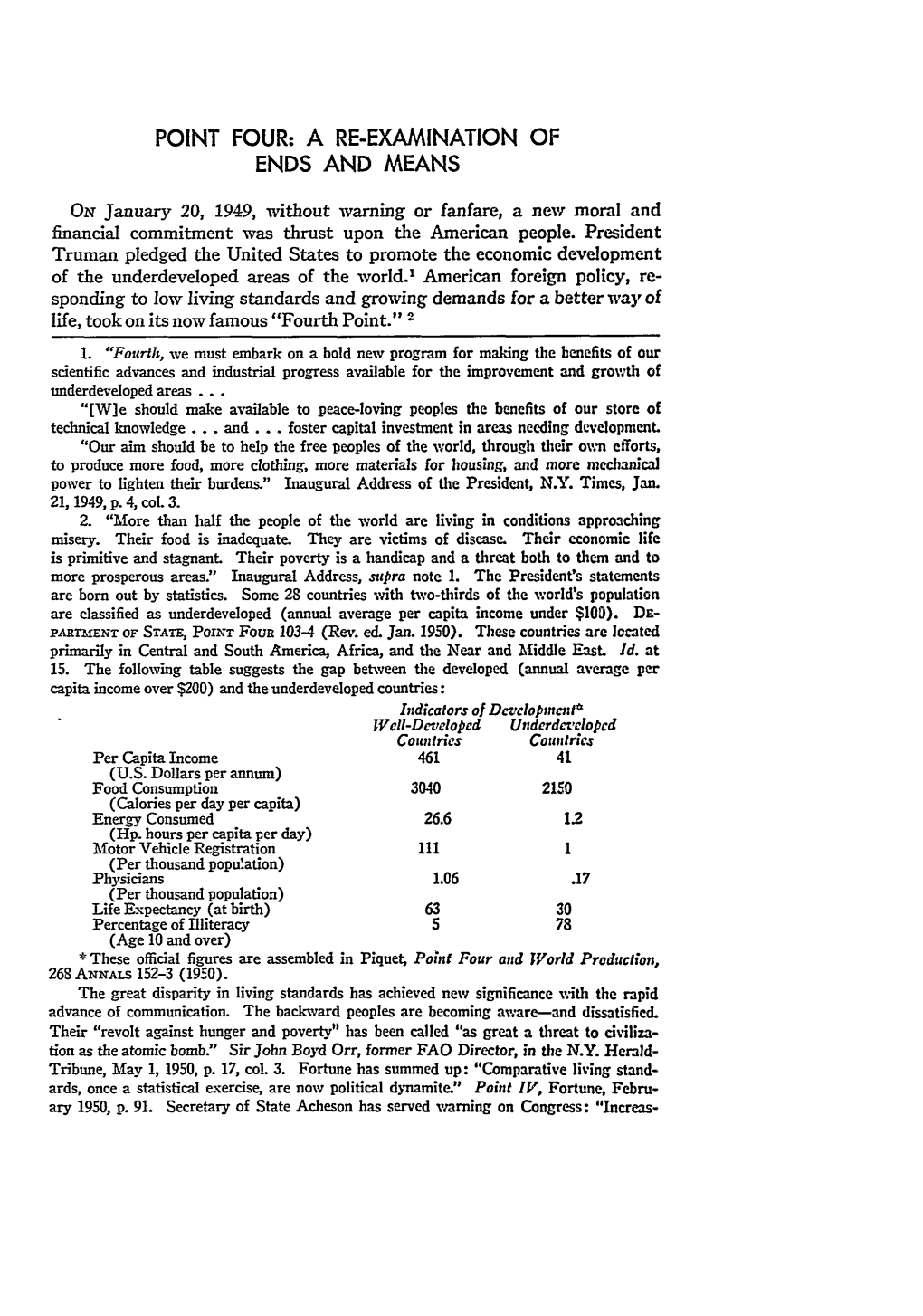

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Strategic Policy and Iranian Political Development 1943-1979

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1985 American strategic policy and Iranian political development 1943-1979 Mohsen Shabdar The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Shabdar, Mohsen, "American strategic policy and Iranian political development 1943-1979" (1985). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5189. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5189 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished manuscript in which copyright sub s is t s , Any further r epr in tin g of it s contents must be approved BY THE AUTHOR, Man sfield L ibrary Un iv e r s it y of Montana Date : •*' 1 8 AMERICAN STRATEGIC POLICY AND IRANIAN POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT 1943-1979 By Mohsen Shabdar B.A., Rocky Mountain College, 1983 Presented in partial fu lfillm e n t of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1985 Approved by: ‘ Chairman, Board of Examir\efs Dean, Graduate School UMI Number: EP40653 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Point Four Program

- [COMMITTEE PRIT]ltE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS POINT FOUR BACKGROUND AND PROGRAM (International Technical Cooperation Act of 1949) Prepared forthe use of the Committee on Foreign'Affairs of the House of Representatives by the Legislative Reference Service, Library of Congress, largely from materials supplied by the Department of State. JULY 1949 UNITED STATES GOVEIWMENT PRINTING OFFICE 9403 WASflNGTON 1949 3L A u ! ' ' , /' ' ". I I t '.t " .' I " COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS JOHN I&EE, West Virginia, Chairman JAmES P. RICHARDS, South Carolina OHARLES A. EATON, Newlersey jOSEPH L. PFEIFER, New York ROBERT B. OHIFJDRFIELD, Illinois THOMAS S.,GORDON, Iinois JOHN M. VORYS, Ohio 'HELEN GAIAGAN DOUGIAAS; eChIfornladFRANCES p1.-BOLTN, bhio. MIKE MAN5FIEID,.Montana LAWRENCE H. SMITA WisconS~ 'THOMAS E. MORGAN, Fensylvanlma CHESTER E IERROW, New flampshir LAURIE 0. BATTLE, Alabama WALTER H. JUDD, Mumnesgd GEORGE A. SMATHERS, Florida iAMES G: FUtTON,.'urindvahi A. S. J. CARNAHAN, Missouri JACOB K. YAVITS, New York ,THURMOND CHATHAM, North Carolina JOHN DAVIS LODGE, Connecticut , CLEMENT X. ZADLOCKI, Wisconsin DONALD L. JACKSON California A. A. RIBICOFF, Connecticut OMIAR BURLESON, Texas BOYD ORAWFORD, Adminrstrative O0.fer and Committee Clerk ~CiARLEs B. MARSHAL, Staff Cqsintn faA E. BENNETT, Staff Consultant JUNE NIoin, StaffAveitant WINIFRED OSBORNE, SlaffAnifstanl DoRIS LEONE, StaffAsewest MABEL HENDERSON, SlaffAzssua7t MAny G, GRACE, Staff Assstant II -0/- _ 2 S LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LEGISLATIVE RrFrRENCE SERVICE, Washington 25, D. C., July 20, Hon. Jon Kmz, 1949. C7 irman, Committee on ForeignAffairs, Uouse of Representatives, Washington, D. C. DEAR JUDGE.Kmg: The report Point Four: Background and Pro gram is trausmitted herewith in response to your recent request. -

The Economics of International Aid

WP 2003-39 November 2003 Working Paper Department of Applied Economics and Management Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853-7801 USA THE ECONOMICS OF INTERNATIONAL AID Ravi Kanbur It is the Policy of Cornell University actively to support equality of educational and employment opportunity. No person shall be denied admission to any educational program or activity or be denied employment on the basis of any legally prohibited discrimination involving, but not limited to, such factors as race, color, creed, religion, national or ethnic origin, sex, age or handicap. The University is committed to the maintenance of affirmative action programs which will assure the continuation of such equality of opportunity. The Economics of International Aid* By Ravi Kanbur Cornell University [email protected] This Version: November, 2003 Contents 1. Introduction 2. The History of Aid 2.1 The Origins of Modern Aid 2.2 Evolution of the Aid Doctrine Before and After the Cold War 3. The Theory of Aid 3.1 Unconditional Transfers 3.2 Conditionality 4. Empirics and Institutions of Aid 4.1 Development Impact of Aid 4.2 Aid Dependence 4.3 International Public Goods and Aid 5. Conclusion References Abstract This paper presents an overview of the economics of international aid, highlighting the historical literature and the contemporary debates. It reviews the “trade-theoretic” and the “contract-theoretic” analytical literature, and the empirical and institutional literature. It demonstrates a great degree of continuity in the policy concerns of the aid discourse in the twentieth century, and shows how the theoretical, empirical and institutional literature has evolved to address specific policy concerns of each period. -

On the Internal Border: Colonial Difference, the Cold War, and the Locations of "Underdevelopment" Alyosha Goldstein

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies Faculty and Staff ubP lications American Studies 2008 On the Internal Border: Colonial Difference, the Cold War, and the Locations of "Underdevelopment" Alyosha Goldstein Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_fsp Recommended Citation Comparative Studies in Society and History 2008;50(1):26-56 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the American Studies at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies Faculty and Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comparative Studies in Society and History 2008;50(1):26–56. 0010-4175/08 $15.00 # 2008 Society for Comparative Study of Society and History DOI: 10.1017/S0010417508000042 On the Internal Border: Colonial Difference, the Cold War, and the Locations of “Underdevelopment” ALYOSHA GOLDSTEIN American Studies, University of New Mexico In 1962, the recently established Peace Corps announced plans for an intensive field training initiative that would acclimate the agency’s burgeoning multitude of volunteers to the conditions of poverty in “underdeveloped” countries and immerse them in “foreign” cultures ostensibly similar to where they would be later stationed. This training was designed to be “as realistic as possible, to give volunteers a ‘feel’ of the situation they will face.” With this purpose in mind, the Second Annual Report of the Peace Corps recounted, “Trainees bound for social work in Colombian city slums were given on-the-job training in New York City’s Spanish Harlem... -

Download Handouts

Background Essay on Point Four Program _____________________________________________ On a frosty January 20th, 1949, after a dramatic re- election campaign, President Harry S. Truman delivered his Second Inaugural Address. In this speech, Truman described his foreign policy goals in four direct points. The fourth point, which has become known as the Point Four Program, took the country by surprise. This fourth point declared that the United States would “embark on a bold new program for making the benefits of our scientific advances and industrial progress available for the improvement and growth of underdeveloped areas.” Truman’s Point Four proposal, along with the much larger Marshall Plan, would not be a totally new idea. W hat was new was how Truman made a connection between foreign aid and freedom. “- Greater production is the key to prosperity and peace. And the key to greater production is a wider and more vigorous application of modern scientific and technical know ledge. - Only by helping the least fortunate of its members to help themselves can the human family achieve the decent, satisfying life that is the right of all people. - Democracy alone can supply the vitalizing force to stir the peoples of the w orld into triumphant action, not only against their human oppressors, but also against their ancient enemies- hunger, misery, and despair. - On the basis of these four major courses of action we hope to help create the conditions that will lead eventually to personal freedom and happiness for all mankind.” In 1949 the need for American aid in the world was great. European and Asian nations were still recovering from the destruction left behind by W W II. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Foreign Assistance Series

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Foreign Assistance Series WILLIAM HAVEN NORTH Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: February 18, 1993 Copyright 1998 ADST The oral history program was made possible through support provided by the Center for Development Information and Evaluation, U.S. Agency for International Development, under terms of Cooperative Agreement No. AEP-0085-A-00-5026-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. TABLE OF CONTENTS Family Background and education Technical Cooperation Administration: First assignment 1952 Ethiopia 1953 Remnants of the ECA program and new programs for Africa 1958 USAID: Nigeria 1961 New development program Sabbatical at Harvard’s Center for International Affairs 1965 Director for Central and West Africa Korry Report Ghana debt crisis Nigerian Civil war 1982 Mission Director for USAID in Ghana 1970 Appointment as Deputy Assistant Administrator 1976 Bureau for Africa USAID 1 Rural Development: Nepal 1983 African Development Foundation Concluding remarks INTERVIEW Q: Today is February 18, 1993. This is an interview on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training with William Haven North and I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. Haven, could you give me a bit about your background to begin with. When you were born, where and a little about your education and maybe family and growing up. Family background and education NORTH: I was born on August 17, 1926 in Summit, New Jersey where my parents had lived for some time. -

Point Four and Latin America

University of Miami Law Review Volume 4 Number 4 Article 6 6-1-1950 Point Four and Latin America Robert Carlyle Beyer Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Recommended Citation Robert Carlyle Beyer, Point Four and Latin America, 4 U. Miami L. Rev. 454 (1950) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol4/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POINT FOUR AND LATIN AMERICA ROBERT CARLYLE BEYER* A program of economic aid to the underdeveloped areas of the world, as suggested by President Truman in Point Four of his inaugural address of January 20, 1949, will probably be enacted into law before Congress adjourns. Whether Mr. Truman is correct in describing it as a "bold new program" or whether his opponents are correct in indicting it as a "global WPA," Point Four promises to occupy a place of importance in the world at large. What is the significance of Point Four in our relations with Latin America? The first answer to this question is that the new program rests largely on United States experience, both negative and positive, in Latin America. Although the areas which Congress was most intent in making targets for the immediate application of the program are those areas lying close to communist portions of the world, yet the genesis of the program lies in what we have done and what we have not done in Latin America. -

A Student Learns How to Serve the Man of the House. President Truman's Point IV Program In"1R9n

Fig. 9: A Student learns how to serve the man of the house. President Truman's Point IV Program in"1r9n. Jhe Home Tabriz. Iran 19S4. Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/thld_a_00282 by guest on 28 September 2021 Z. Pamela Karimi Policymaking and Housekeeping President Truman's Point IV Program and the Mal<ing of the Modern Iranian House. Mandates improve Iran's domestic life. The activities of this department The post-WWII period is generally considered one of the were supervised by the U.S. Division of Education and Training, most pivotal in the modernization of many Middle Eastern and were part of President Truman's Point IV Program for countries. Since the early 19505, intervention by the American Iran. The Point IV Program was established to promote U.S. foreign policy and to assist with government in the Middle East has led to changes not only the development of certain economically underdeveloped countries. The Program's sector in the cultural patterns of life and economic structures, but in Iran was meant to improve Iranian industry, communication, also in developments within the realm of architecture - both transportation, general services, housing, and labor. The urban and domestic. Iran offers a perfect means to examine process was carried out through joint operations involving the substance of this process, because as Douglas Little in American officials and various ministries, agencies, and his book American Orientalism reminds us, "nowhere in the institutions of Iran." Each year roughly one-eighth of the Middle East did the United States push more consistently for amount given to each Western European country as part of reform and modernization after 1945 than Iran, and nowhere the Marshall Plan was dedicated to Iran to support housing did America fail more spectacularly."' "What is going on in and education programs. -

The Global Development Alliance: Public-Private

THE GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT ALLIANCE PUBLIC-PRIVATE ALLIANCES FOR TRANSFORMATIONAL DEVELOPMENT U.S. Agency for International Development Office of Global Development Alliances www.usaid.gov/gda General Information: 202-712-0600 Published January 2006 Prepared by Management Systems International, Inc., www.msiworldwide.com Design and production by Meadows Design Office Inc., www.mdomedia.com CONTENTS A word on partnership from the President of the United States 7 Preface 7 Foreword 8 Welcome 11 PART 1: THE GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT ALLIANCE BUSINESS MODEL CHAPTER ONE THE PRIVATE REVOLUTION IN GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT 14 The tightening web of economic exchange between the developing and industrialized worlds 14 International development concerns us all 15 New players, new money 17 More aid, for countries that use it well 18 A new mindset for new challenges 19 Origins of the Global Development Alliance 20 CHAPTER TWO BUILDING DEVELOPMENT ALLIANCES THE GDA MODEL AT WORK 25 Who participates in alliances, and why? 25 Conceiving, developing, and implementing an alliance 28 U.S. Agency for International Development funding mechanisms 30 How have alliance partners had to adapt to make alliances work? 30 Evaluating alliances for effectiveness 32 Reading the cases that follow 34 PART I1: ALLIANCE STORIES CHAPTER THREE SUSTAINABLE SUPPLY CHAINS RAISING STANDARDS, BUILDING TRADE 36 Sustainable Tree Crops Program Alliance: helping the smallholder farmer in Africa 38 Sustainable Forest Products Global Alliance: making markets work for forests and people 43 Conservation -

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution

CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Note on Usage ix Introduction 3 1 Forging a Partnership for Development: Point Four and American Universities 14 2 Utahns in Iran 34 3 Point Four and the Iranian Political Crisis of 1951–1953 56 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL 4 To Make the Iranian Desert Bloom 80 NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION 5 Modernizing Iranian Education 111 6 Legacies 135 Afterword 161 Notes 165 Bibliography 213 About the Author 229 Index 231 INTRODUCTION The United States must devise a means to develop Iran for the benefit of all its people. T. Cuyler Young, 1950 Bruce Anderson was just trying to finish a master’s degree in agricultural engineering atCOPYRIGHTED Utah State University (USU) inMATERIAL mid-1951 when he encountered an opportunity that changed his life. His research on an irrigation canal in Vernal had stalledNOT when his FOR adviser, DISTRIBUTION Cleve Milligan, suggested that Bruce accompany him on a new venture USU was organizing halfway around the world in Iran. The university had agreed to send specialists to help the Iranian Ministry of Agriculture improve farm production, and Milligan had been chosen to head the project’s engineering operation. He could use another irrigation specialist, and Anderson would no doubt find plenty of suitable research projects in that mostly arid country. As exciting as the prospect sounded, it also inspired “fear and trembling” in this married father of four who had difficulty finding the country on a map. Nevertheless, the families DOI: 10.7330/9781607327547.c000 4 INTRODUCTION of Bruce Anderson, Cleve Milligan, and three of their USU colleagues set off for Tehran that September.1 The Anderson family spent most of the next decade living in Iran, first in and around the historic southern city of Shiraz and later in the sprawling capital of Tehran. -

1956 £ . M Z . Y

i li1'it/i’ 1 L A ' . n G G U C . ' . j G A i i) ' U i .-D I A A.. D i i iij 1 D.i a AGACiJG. : A i OL.i.Til CAL AUAi.YS l.'S D 1 SSLKTAT.J ON. I resented in Partial Ful fillmen I of ehe Roqu j i-omen t s fur the Degree Doetoi' of Philosophy in uhe Graduate School of the Ohio Stat.e Uni versity By CHARLIE LYONS JR., ii. A., A. W. The Ohio State University 1956 Approved by? ■ £ . m z . y u ^ Adviser Department of Political Science AC1C. GW L E D G E J IE E '!'S -li.is sci!tly was made unde;' the superv »sion o f Dr. E. Allen helms, Pi'oi'essu)' uf Political Science, the Chio State University. The writer is extremely grateful i'or i.he critical and constructive advice and assistance of the members of the Supervisory Conuui ttee at the Ohio State Universi ty and of his advisers at the Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, Poona, India. Special thanks and appreciation should go to the following persons: Dr. E. Allen Helms Professor of Political Science The Ohio State University Dr. Louis Nemzer Associate Professor of Political Science The Ohio State University Dr. ICazuo Kawai Associate Professor of Political Science The Ohio State University Dr. D. R. Gadgil, Director Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics Poona, India ^ ‘ Dr. N. V. Sovani, Assistant Director Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics Poena, India The writer would also like to acknowledge a debt of gratitude to Mr. -

Passage and Implementation of Point Four in United States Diplomacy

THE PASSAGE AND IMPLEMENTATION OF POINT FOUR IN UNITED STATES DIPLOMACY by CARROL MARY SACHTJEN A. B., Nebraska State Teachers College, Wayne, Nebraska, 1951 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of History, Government, and Philosophy KANSAS STATE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND APPLIED SCIENCE 1953 / - Coco- c 1153 CZ TABLE OF CONTENTS i. PRJiFACE ill INTRODUCTION 1 POINT POUR DURING THE PIKST SESSION OP THE 81ST CONGRESS 15 PASSAGE OP THE BILL 49 THE ROLE OP THE STATE DEPARTMENT IN THE PASSAGE OF POINT POUR 85 THE IMPLEMENTATION OP POINT POUR 100 BIBLIOGRAPHY 123 APPENDIX 127 iii PREFACE On January 20, 1949, President Truman in his inaugural ad- dress laid the foundation for what was to he known as Point Pour. This plan was to make available to peace-loving peoples the ben- efits of the United States store of technical knowledge and to foster capital investments in the areas needing development. The purpose of this study is to present to the reader the conflicting attitudes and the various interpretations in regard to the Point Pour program. Idealists sat/ in the concept an op- portunity without parallel to extend to all who want them, the standard of living and the way of life that had made the United States envied among nations. Skeptics suspected we were being tricked into dissipating our resources in a task we could never expect to complete, leaving the United States prey to a cynical enemy who hopefully awaited our economic ruin. Between these two extremes students of the idea saw an opportunity to foster stable governments and contented nations while building up markets for our own exports and sources of the raw materials we need.