September 11: Symbolism and Responses to "9/11"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 179/Tuesday

57282 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 179 / Tuesday, September 15, 2020 / Notices publicly. All submissions should refer The Commission is publishing this will help to ensure that Restrictive to File Number SR–IEX–2020–13 and order to solicit comments on the Market Companies have sufficient should be submitted on or before proposed rule change from interested investor base and public float to support October 6, 2020. persons and to institute proceedings fair and orderly trading on the 12 For the Commission, by the Division of pursuant to Section 19(b)(2)(B) of the Exchange. Specifically, the Exchange 6 Trading and Markets, pursuant to delegated Act to determine whether to approve proposes to adopt a definition of authority.21 or disapprove the proposed rule change. ‘‘Restrictive Market’’ 13 and to apply additional initial listing requirements to J. Matthew DeLesDernier, II. Exchange’s Description of the a Restrictive Market Company listing on Assistant Secretary. Proposed Rule Change the Exchange in connection with an IPO [FR Doc. 2020–20256 Filed 9–14–20; 8:45 am] The Exchange states that in recent or a business combination.14 The BILLING CODE 8011–01–P years the lack of transparency from Exchange also proposes to prohibit a certain emerging markets has raised Restrictive Market Company from listing concerns with respect to listed emerging SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE on the Nasdaq Capital Market in market companies regarding the 15 COMMISSION connection with a Direct Listing, but accuracy of disclosures, accountability, to allow a Restrictive Market Company and access to information, particularly [Release No. 34–89799; File No. -

Payment System Disruptions and the Federal Reserve Followint

Working Paper Series This paper can be downloaded without charge from: http://www.richmondfed.org/publications/ Payment System Disruptions and the Federal Reserve Following September 11, 2001† Jeffrey M. Lacker* Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Richmond, Virginia, 23219, USA December 23, 2003 Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Working Paper 03-16 Abstract The monetary and payment system consequences of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks are reviewed and compared to selected U.S. banking crises. Interbank payment disruptions appear to be the central feature of all the crises reviewed. For some the initial trigger is a credit shock, while for others the initial shock is technological and operational, as in September 11, but for both types the payments system effects are similar. For various reasons, interbank payment disruptions appear likely to recur. Federal Reserve credit extension following September 11 succeeded in massively increasing the supply of banks’ balances to satisfy the disruption-induced increase in demand and thereby ameliorate the effects of the shock. Relatively benign banking conditions helped make Fed credit policy manageable. An interbank payment disruption that coincided with less favorable banking conditions could be more difficult to manage, given current daylight credit policies. Keywords: central bank, Federal Reserve, monetary policy, discount window, payment system, September 11, banking crises, daylight credit. † Prepared for the Carnegie-Rochester Conference on Public Policy, November 21-22, 2003. Exceptional research assistance was provided by Hoossam Malek, Christian Pascasio, and Jeff Kelley. I have benefited from helpful conversations with Marvin Goodfriend, who suggested this topic, David Duttenhofer, Spence Hilton, Sandy Krieger, Helen Mucciolo, John Partlan, Larry Sweet, and Jack Walton, and helpful comments from Stacy Coleman, Connie Horsley, and Brian Madigan. -

REVIEW of the TERRORIST ATTACKS on U.S. FACILITIES in BENGHAZI, LIBYA, SEPTEMBER 11-12,2012

LLIGE - REVIEW of the TERRORIST ATTACKS ON U.S. FACILITIES IN BENGHAZI, LIBYA, SEPTEMBER 11-12,2012 together with ADDITIONAL VIEWS January 15, 2014 SENATE SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE United States Senate 113 th Congress SSCI Review of the Terrorist Attacks on U.S. Facilities in Benghazi, Libya, September 11-12, 2012 I. PURPOSE OF TIDS REPORT The purpose of this report is to review the September 11-12, 2012, terrorist attacks against two U.S. facilities in Benghazi, Libya. This review by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (hereinafter "SSCI" or "the Committee") focuses primarily on the analy~is by and actions of the Intelligence Community (IC) leading up to, during, and immediately following the attacks. The report also addresses, as appropriate, other issues about the attacks as they relate to the Department ofDefense (DoD) and Department of State (State or State Department). It is important to acknowledge at the outset that diplomacy and intelligence collection are inherently risky, and that all risk cannot be eliminated. Diplomatic and intelligence personnel work in high-risk locations all over the world to collect information necessary to prevent future attacks against the United States and our allies. Between 1998 (the year of the terrorist attacks against the U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania) and 2012, 273 significant attacks were carried out against U.S. diplomatic facilities and personnel. 1 The need to place personnel in high-risk locations carries significant vulnerabilities for the United States. The Conimittee intends for this report to help increase security and reduce the risks to our personnel serving overseas and to better explain what happened before, during, and after the attacks. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

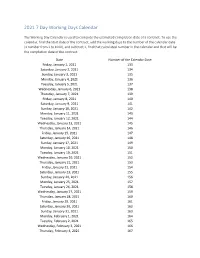

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

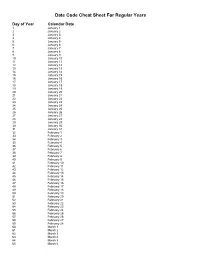

Julian Date Cheat Sheet for Regular Years

Date Code Cheat Sheet For Regular Years Day of Year Calendar Date 1 January 1 2 January 2 3 January 3 4 January 4 5 January 5 6 January 6 7 January 7 8 January 8 9 January 9 10 January 10 11 January 11 12 January 12 13 January 13 14 January 14 15 January 15 16 January 16 17 January 17 18 January 18 19 January 19 20 January 20 21 January 21 22 January 22 23 January 23 24 January 24 25 January 25 26 January 26 27 January 27 28 January 28 29 January 29 30 January 30 31 January 31 32 February 1 33 February 2 34 February 3 35 February 4 36 February 5 37 February 6 38 February 7 39 February 8 40 February 9 41 February 10 42 February 11 43 February 12 44 February 13 45 February 14 46 February 15 47 February 16 48 February 17 49 February 18 50 February 19 51 February 20 52 February 21 53 February 22 54 February 23 55 February 24 56 February 25 57 February 26 58 February 27 59 February 28 60 March 1 61 March 2 62 March 3 63 March 4 64 March 5 65 March 6 66 March 7 67 March 8 68 March 9 69 March 10 70 March 11 71 March 12 72 March 13 73 March 14 74 March 15 75 March 16 76 March 17 77 March 18 78 March 19 79 March 20 80 March 21 81 March 22 82 March 23 83 March 24 84 March 25 85 March 26 86 March 27 87 March 28 88 March 29 89 March 30 90 March 31 91 April 1 92 April 2 93 April 3 94 April 4 95 April 5 96 April 6 97 April 7 98 April 8 99 April 9 100 April 10 101 April 11 102 April 12 103 April 13 104 April 14 105 April 15 106 April 16 107 April 17 108 April 18 109 April 19 110 April 20 111 April 21 112 April 22 113 April 23 114 April 24 115 April -

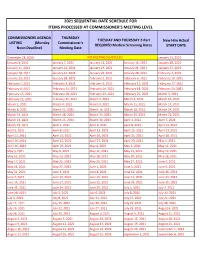

2021 Sequential Date List

2021 SEQUENTIAL DATE SCHEDULE FOR ITEMS PROCESSED AT COMMISSIONER'S MEETING LEVEL COMMISSIONERS AGENDA THURSDAY TUESDAY AND THURSDAY 2-Part New Hire Actual LISTING (Monday Commissioner's REQUIRED Medical Screening Dates START DATE Noon Deadline) Meeting Date December 28, 2020 NO MEETING SCHEDULED January 13, 2021 January 4, 2021 January 7, 2021 January 12, 2021 January 14, 2021 January 20, 2021 January 11, 2021 January 14, 2021 January 19, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 27, 2021 January 18, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 26, 2021 January 28, 2021 February 3, 2021 January 25, 2021 January 28, 2021 February 2, 2021 February 4, 2021 February 10, 2021 February 1, 2021 February 4, 2021 February 9, 2021 February 11, 2021 February 17, 2021 February 8, 2021 February 11, 2021 February 16, 2021 February 18, 2021 February 24, 2021 February 15, 2021 February 18, 2021 February 23, 2021 February 25, 2021 March 3, 2021 February 22, 2021 February 25, 2021 March 2, 2021 March 4, 2021 March 10, 2021 March 1, 2021 March 4, 2021 March 9, 2021 March 11, 2021 March 17, 2021 March 8, 2021 March 11, 2021 March 16, 2021 March 18, 2021 March 24, 2021 March 15, 2021 March 18, 2021 March 23, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 31, 2021 March 22, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 30, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 7, 2021 March 29, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 6, 2021 April 8, 2021 April 14, 2021 April 5, 2021 April 8, 2021 April 13, 2021 April 15, 2021 April 21, 2021 April 12, 2021 April 15, 2021 April 20, 2021 April 22, 2021 April 28, 2021 April 19, 2021 April 22, 2021 April 27, 2021 April -

FDNY Fire Operations Response on September 11

FDNY Fire Operations response on September 11 This section of our report describes the major aspects of the response of FDNY Fire Operations to the World Trade Center attack. It has four parts. The first describes how FDNY commanders exercised overall command and control of fire operations at the scene. The second deals more specifically with how those commanders deployed and managed personnel and resources. The third describes how the Fire Department handled planning of its resource requirements on September 11 and afterwards, and how the Fire Department managed logistics (i.e., deployment of supplies and equipment). The fourth discusses the challenges faced by the Department as it sought to support and counsel its members and their families in the aftermath of September 11. COMMAND, CONTROL AND COMMUNICATIONS The FDNY’s response to the attacks of September 11 began at 8:46 a.m., the moment that American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into Tower 1 of the World Trade Center (WTC 1). Command is established The Battalion Chief assigned to Battalion 1 (B1)10 witnessed the impact of the plane from the corner of Church and Lispenard Streets. He immediately signaled a second alarm11 and proceeded to the World Trade Center. En route, B1 requested additional resources by transmitting a third alarm at 8:48 a.m. B1 informed the FDNY Communications Office (Dispatch) that the corner of West and Vesey Streets, one block north of WTC 1, would be the designated staging area for third alarm units.12 B1 arrived at WTC 1 at approximately 8:50 a.m. -

Pay Date Calendar

Pay Date Information Select the pay period start date that coincides with your first day of employment. Pay Period Pay Period Begins (Sunday) Pay Period Ends (Saturday) Official Pay Date (Thursday)* 1 January 10, 2016 January 23, 2016 February 4, 2016 2 January 24, 2016 February 6, 2016 February 18, 2016 3 February 7, 2016 February 20, 2016 March 3, 2016 4 February 21, 2016 March 5, 2016 March 17, 2016 5 March 6, 2016 March 19, 2016 March 31, 2016 6 March 20, 2016 April 2, 2016 April 14, 2016 7 April 3, 2016 April 16, 2016 April 28, 2016 8 April 17, 2016 April 30, 2016 May 12, 2016 9 May 1, 2016 May 14, 2016 May 26, 2016 10 May 15, 2016 May 28, 2016 June 9, 2016 11 May 29, 2016 June 11, 2016 June 23, 2016 12 June 12, 2016 June 25, 2016 July 7, 2016 13 June 26, 2016 July 9, 2016 July 21, 2016 14 July 10, 2016 July 23, 2016 August 4, 2016 15 July 24, 2016 August 6, 2016 August 18, 2016 16 August 7, 2016 August 20, 2016 September 1, 2016 17 August 21, 2016 September 3, 2016 September 15, 2016 18 September 4, 2016 September 17, 2016 September 29, 2016 19 September 18, 2016 October 1, 2016 October 13, 2016 20 October 2, 2016 October 15, 2016 October 27, 2016 21 October 16, 2016 October 29, 2016 November 10, 2016 22 October 30, 2016 November 12, 2016 November 24, 2016 23 November 13, 2016 November 26, 2016 December 8, 2016 24 November 27, 2016 December 10, 2016 December 22, 2016 25 December 11, 2016 December 24, 2016 January 5, 2017 26 December 25, 2016 January 7, 2017 January 19, 2017 1 January 8, 2017 January 21, 2017 February 2, 2017 2 January -

2021 Calendar Campaign

One Tail at a Time 2021 Calendar Pets Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Friday, January 1 Not Available Saturday, February 20 Not Available Sunday, April 11 Available Monday, May 31 Not Available Tuesday, July 20 Available Wednesday, September 8 Not Available Thursday, October 28 Available Thursday, December 16 Available Saturday, January 2 Available Sunday, February 21 Available Monday, April 12 Not Available Tuesday, June 1 Available Wednesday, July 21 Not Available Thursday, September 9 Available Friday, October 29 Available Friday, December 17 Available Sunday, January 3 Available Monday, February 22 Available Tuesday, April 13 Available Wednesday, June 2 Available Thursday, July 22 Not Available Friday, September 10 Available Saturday, October 30 Available Saturday, December 18 Not Available Monday, January 4 Available Tuesday, February 23 Available Wednesday, April 14 Available Thursday, June 3 Available Friday, July 23 Available Saturday, September 11 Available Sunday, October 31 Not Available Sunday, December 19 Available Tuesday, January 5 Available Wednesday, February 24 Available Thursday, April 15 Not Available Friday, June 4 Available Saturday, July 24 Available Sunday, September 12 Available Monday, November 1 Available Monday, December 20 Available Wednesday, January 6 Available Thursday, February 25 Available Friday, April 16 Not Available Saturday, June 5 Available Sunday, July 25 Available Monday, September 13 Available Tuesday, November 2 Available Tuesday, -

2020 DRC and Planning Board Schedule for Sketch Plans (90 Day Schedule)

2020 DRC and Planning Board Schedule for Sketch Plans (90 day Schedule) Comments from Staff on First Final Recommendation From Final Date to Post Staff Report on Planning Board Public Hearing Date DRC Distribution Date DRC with Applicant Applicant's First Resubmission Resubmission Applicant's Final Submission Review Agencies Plannning Board's Website (1) Monday, December 23, 2019 Tuesday, January 7, 2020 Tuesday, January 21, 2020 Friday, January 31, 2020 Monday, February 10, 2020 Tuesday, February 18, 2020 Monday, March 2, 2020 Thursday, March 12, 2020 Monday, January 6, 2020 Tuesday, January 21, 2020 Tuesday, February 4, 2020 Friday, February 14, 2020 Monday, February 24, 2020 Tuesday, March 3, 2020 Monday, March 16, 2020 Thursday, March 26, 2020 Tuesday, January 21, 2020 Tuesday, February 4, 2020 Tuesday, February 18, 2020 Friday, February 28, 2020 Monday, March 9, 2020 Tuesday, March 17, 2020 Monday, March 30, 2020 Thursday, April 9, 2020 Monday, February 3, 2020 Tuesday, February 18, 2020 Tuesday, March 3, 2020 Friday, March 13, 2020 Monday, March 23, 2020 Tuesday, March 31, 2020 Monday, April 13, 2020 Thursday, April 23, 2020 Monday, February 17, 2020 Tuesday, March 3, 2020 Tuesday, March 17, 2020 Friday, March 27, 2020 Monday, April 6, 2020 Tuesday, April 14, 2020 Monday, April 27, 2020 Thursday, May 7, 2020 Monday, March 2, 2020 Tuesday, March 17, 2020 Tuesday, March 31, 2020 Friday, April 10, 2020 Monday, April 20, 2020 Tuesday, April 28, 2020 Monday, May 11, 2020 Thursday, May 21, 2020 Monday, March 16, 2020 Tuesday, March 31, -

SEPTEMBER 11, 2001, TERRORIST ATTACKS— Sept

CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—SEPT. 26, 2001 115 STAT. 2525 preparations for the vigil shall be carried out in accordance with such conditions as the -Aj-chitect of the Capitol may prescribe. Agreed to September 12, 2001. SEPTEMBER 11, 2001, TERRORIST ATTACKS— Sept. 13,2001 NATIONAL REMEMBERANCE AND SOLIDARITY [H. Con. Res. 225] Whereas on September 11, 2001, terrorists hijacked and destroyed four commercial aircraft, crashing two of them into the World Trade Center in New York City, and crashing another aircraft into the Pentagon outside Washington, D.C.; and Whereas thousands of innocent people were killed and injured as a result of those attacks, including the passengers and crew of the four aircraft, workers and visitors in the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, rescue workers, and bystanders: Now, therefore, be it Resolved by the House of Representatives (the Senate concurring), That it is the sense of the Congress that— (1) in response to the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001, United States citizens should join together to defend and honor the Nation and its symbols of strength; and (2) for a period of 30 days after the date on which this resolution is agreed to, each United States citizen and every community in the Nation is encouraged to display the flag of the United States at homes, places of work and business, public buildings, and places of worship to remember those individuals who have been lost and to show the solidarity, resolve, and strength of the Nation. Agreed to September 13, 2001. JOINT SESSION Sept. 19,2001 [H.