An Approach for Measuring Partisan Segregation in Political Media Consumption PARTISAN SEGREGATION 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

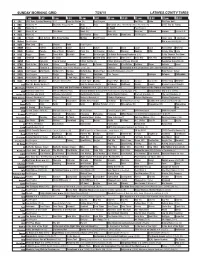

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

Businesses Brace for Energy Cost Increases

newsJUNE 2011 We all influence the health of those around us, especially in the work place. As an employer, you have a tremendous effect on employee health by the examples you set and the health care plans you choose. As a Kentucky Chamber Businesses member, you’re connected to big savings on big benefits for your small business. Help employees get more involved in their health care with consumer-driven HSA, HRA and HIA plans, or choose from more traditional solutions. Either way, brace for you can build a complete benefits package – including preventive care and prescription coverage – with one-stop shopping convenience. energy cost Talk to your broker, call the Kentucky Chamber at 800-431-6833 or visit increases group.anthem.com/kcoc for more information. PAGE 1 Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield is the trade name of Anthem Health Plans of Kentucky, Inc. Life and Disability products underwritten by Anthem Life Insurance Company. Independent licensees of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association. ® ANTHEM is a registered trademark of Anthem Insurance Companies, Inc. The Blue Cross and Blue Shield names and symbols are registered marks of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association. 19075KYAENABS 1/11 JUNE 2011 Business Summit and Annual Meeting Businesses Morning Joe hosts brace for to share their views energy cost at Annual Meeting ONE OF CABLE television’s highest rated morning increases talk shows, MSNBC’s Morning Joe, is not just a NEW DATA from Kentucky’s regulated news source — it’s also been, at times, a newsmak- electric utility companies shows that the er. -

When Parody and Reality Collide: Examining the Effects of Colbert's

International Journal of Communication 7 (2013), 394–413 1932–8036/20130005 When Parody and Reality Collide: Examining the Effects of Colbert’s Super PAC Satire on Issue Knowledge and Policy Engagement Across Media Formats HEATHER LAMARRE University of Minnesota See the companion work to this article “Shifting the Conversation: Colbert’s Super PAC and the Measurement of Satirical Efficacy” by Amber Day in this Special Section Following the 2010 U.S. Supreme Court landmark decision on campaign finance (i.e., Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission), political comedian Stephen Colbert took to the airways with a new kind of entertainment-based political commentary; satirical political activism. Colbert’s creation of a super PAC garnered the attention of national media, providing him the opportunity to move his satire beyond the confines of his late- night comedy show (The Colbert Report). Transcending traditional boundaries of late- night political comedy, Colbert appeared in character on a variety of political talk shows. Meta-coverage of this collision between parody and reality begs the question: Do audiences who consume Colbert’s super PAC parody in different media contexts demonstrate significantly different effects? Using data from a Web-based experiment (N = 112), effects of consuming Colbert’s super PAC satire in different media contexts (political comedy show, political talk show) were compared. Results indicate that consuming Colbert’s super PAC parody in the context of his comedy show resulted in significantly higher levels of issue knowledge and support for campaign finance reform when compared with those who consumed Colbert’s super PAC parody in the context of a political talk show (Morning Joe). -

An Overview of Federal STEM Education Programs

Invisible: 1.4 Percent Coverage for Education is Not Enough Darrell M. West, Grover J. “Russ” Whitehurst, and E.J. Dionne Jr. Methodology • Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism - Coded content daily from a sample of newspapers, network news, cable news, news and talk radio, and online news - Samples are purposeful rather than representative - Selection bias for important stories • Brookings: coded content of all AP education wire stories • Brookings: qualitative study of blogs and local newspapers Newspapers Online Network TV Cable Radio Yahoo news ABC Good CNN daytime NPR Morning Edition NY Times Morning America MSNBC.com ABC World News Situation Room Rush Limbaugh Washington Post Tonight Wall Street Journal NYTimes.com NBC Today Show Anderson Cooper 360 Ed Schultz USA Today Google news NBC Nightly News Lou Dobbs Randi Rhodes washingtonpost.com CBS The Early CNN Prime Time Michael Savage LA Times Show cnn.com CBS Evening MSNBC daytime Sean Hannity Kansas City Star News Pittsburgh Post- aol news PBS Newshour Hardball ABC News Gazette Headlines San Antonio foxnews.com Rachel Maddow CBS News Express-News Headlines San Jose Mercury USAtoday.com The Ed Show News Herald News abcnews.com Countdown Anniston Star BBC News Fox News special Spokesman-Review Reuters.com Fox News daytime Meadville Tribune O'Reilly Factor Fox Report with Shepard Smith Hannity (TV) Special Report w/ Bret Baier Government National News Coverage 2009 Economics Foreign (non-U.S.) U.S. Foreign affairs 12 Health/Medicine Business Crime 10 Campaign/Elections/Politics -

Ahca/Ncalin the News

THE GAZETTE ONLINE AND PRINTABLE VERSIONS AVAILABLE AT HTTP://AHCA.BULLETINNEWS.COM DATE: TUESDAY, APRIL 1, 2014 8:00 AM EDT TODAY’S EDITION AHCA/NCAL in the News Medicare News Washington Health Care Association Branch Awards Senate Approves Medicare Payment Patch Legislation. .............. 6 “Outstanding Work” In The Industry. .................................... 1 Senate Approves Bill To Reduce Payments To Doctors For Affordable Care Act/Health Reform Implementation Certain Medical Procedures. ................................................ 7 ACA Enrollment Nears Seven Million As Deadline Spurs Cardiac Rehab Programs Now Covered By Medicare. ................ 7 Interest, Hobbles Website. ................................................... 1 Blog: Journalists Overlooking Protecting Access To Medicare States See Surge In Interest, Technical Problems As Open Act Of 2014. .......................................................................... 7 Enrollment Ends. .................................................................. 3 Industry News Sebelius Discusses ACA As Open Enrollment Draws To A American Heart, Stroke Associations Release Stroke Survivor Close. .................................................................................... 4 Care Recommendations....................................................... 7 Poll: Support For ACA Climbs To 49%. ........................................ 5 Expert Panel Releases Recommendations. ................................. 7 Supreme Court Turns Away Early Look At Additional NYTimes Reviews -

Ruth Marcus Experience The

RUTH MARCUS EXPERIENCE THE WASHINGTON POST 2016-Present: Deputy editorial page editor. Oversee oped pages and all signed opinion content. Review oped submissions, hire and manage columnists and bloggers, develop multi- platform content including video, chart strategic direction of opinion section and develop digital strategy. As member of editorial board attend editorial board meetings and help shape editorial positions. 2006-Present: Columnist. Write opinion column for oped page and, beginning in 2008, for syndicated newspaper clients, focusing on domestic politics and policy. Finalist, Pulitzer Prize for commentary, 2007. “The week” columnist of the year, 2008. 2003-2015: Editorial writer. Write editorials on domestic policy and politics, including budget and taxes, health care, money and politics. 1999-2003: Deputy National Editor. Oversee staff coverage of campaign finance and lobbying and national politics; direct coverage of 2000 recount. 1986-1999: National Staff Reporter covering White House, Supreme Court, Justice Department, national politics, money and politics. 1984-1987: Metro staff reporter covering local development and legal issues. Wrote weekly column on law and lawyers. Covered “Year of the Spy” espionage cases. EXTRACURRICULAR: 2017-Present: MSNBC/NBC news contributor. Appear several times weekly on MSBC shows, including Morning Joe, Andrea Mitchell Reports, Hardball, Last Word, Meet the Press and Meet the Press Daily. Previously: Regular guest on ABC’s “This Week,” CBS “Face the Nation,” CNN, Fox News Frequent guest and moderator on panels, including Atlantic Festival, Aspen Ideas Festival, New Yorker Festival, Brookings Institution. EDUCATION 1981-1984: Harvard Law School, magna cum laude, Harvard Law Review 1975-1979: Yale College, cum laude, with distinction in history Error! Bookmark not defined. -

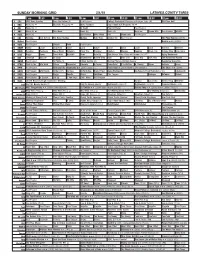

Sunday Morning Grid 7/26/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/26/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Res. Faldo PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Volleyball 2015 FIVB World Grand Prix, Final. (N) 2015 Tour de France 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Outback Explore Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Rio ››› (2011) (G) 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Contac Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap (TVG) Celtic Thunder The Show 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Cinderella Man ››› 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Tras la Verdad Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Hungria 2015. -

Fiduciary Duty and the Public Interest

FIDUCIARY DUTY AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST CHERYL L. WADE∗ INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1191 I. SUBPRIME LENDERS, SHAREHOLDERS, CONSUMERS, AND COMMUNITIES ................................................................................... 1193 II. PREDATORY LENDERS AND THE FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS THAT DID BUSINESS WITH THEM ................................................................ 1196 III. PUBLIC OPINION, DISCOURSE, AND FIDUCIARY DUTY. ...................... 1203 CONCLUSION ................................................................................................. 1207 INTRODUCTION Professor Tamar Frankel’s excellent book, Fiduciary Law, is a thorough and comprehensive look at the fiduciary-law forest. My contribution to the Symposium on The Role of Fiduciary Law and Trust in the Twenty-First Century is one leaf on one branch of one tree in the forest that Professor Frankel so expertly navigates. In this Essay, I explore the fiduciary relationship between corporate directors and officers and the shareholders they serve. I examine how the breach of fiduciary duties owed to shareholders has the power to dramatically impact non-shareholder groups. Professor Frankel accurately observes that “[f]iduciary duties are anchored in the interests of the parties to the relationship rather than the public’s interests.”1 But her statement ignores the expansive reach and impact of fiduciary law in general and fiduciary duty breach in particular. Corporate fiduciaries’ -

National,Network Cable Spot Daily Calendar

Spot Daily Calendar National,Network Cable Client: Coalition to Protect Americas Health Care Flight Dates: Monday, March 24, 2014 to Sunday, March 30, 2014 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 03/24/14 03/25/14 03/26/14 03/27/14 03/28/14 03/29/14 03/30/14 Early Morning Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews FXNC-TV: Fox & FXNC-TV: Fox & FXNC-TV: Fox & FXNC-TV: Fox & FXNC-TV: Fox & Friends Friends Friends Friends Friends 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 2 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x Ch MSNBC Ch MSNBC Ch MSNBC Ch MSNBC Ch MSNBC MNBC-TV: Morning Joe MNBC-TV: Morning Joe MNBC-TV: Morning Joe MNBC-TV: Morning Joe MNBC-TV: Morning Joe 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 2 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x Daytime Ch CNN Ch CNN Ch CNN Ch CNN Ch CNN CNN-TV: CNN New CNN-TV: CNN New CNN-TV: CNN New CNN-TV: CNN New CNN-TV: CNN New Day Morning News Day Morning News Day Morning News Day Morning News Day Morning News 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 2 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x Ch CNN Ch CNN CNN-TV: CNN CNN-TV: CNN Newsroom 9am Newsroom 9am 9:00 AM 10:00 AM 1 x 9:00 AM 10:00 AM 1 x Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews FXNC-TV: Fox News FXNC-TV: Fox News FXNC-TV: Fox News FXNC-TV: Fox News Daytime Daytime Daytime Daytime 9:00 AM 12:00 PM 1 x 9:00 AM 12:00 PM 1 x 9:00 AM 12:00 PM 1 x 9:00 AM 12:00 PM 1 x Ch CNN Ch CNN Ch CNN CNN-TV: CNN News CNN-TV: CNN News CNN-TV: CNN News Daytime Daytime Daytime 10:00 AM -

Sunday Morning Grid 2/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan at Michigan State. (N) PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Make Football Super Bowl XLIX Pregame (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Kids News Animal Sci Paid Program The Polar Express (2004) 13 MyNet Paid Program Bernie ››› (2011) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Atrévete 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki Doki (TVY) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part III 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

MSNBC HD Now Available Nationwide on DISH Network

MSNBC HD Now Available Nationwide on DISH Network Englewood, Colo. – July 9, 2009 – DISH Network today introduced MSNBC HD, becoming the first pay-TV provider to offer the channel to consumers nationwide. “As the leader in high definition programming with more than 140 national HD channels, we are pleased to be the only pay-TV provider to offer MSNBC HD nationwide,”said Dave Shull, senior vice president of Programming for DISH Network. “Nowhere else will consumers find the variety of HD programming and award-winning DVR technology at the low everyday prices that DISH Network offers.” “MSNBC is in the best competitive place it’s ever been, beating CNN in primetime and continuing incredible growth,”said Phil Griffin, President, MSNBC. “Broadcasting in HD is only going to help us build on the great success we’ve had so far this year, and will give viewers what they’ve been asking for, a full high definition broadcast of MSNBC.” DISH Network customers will now be able to watch MSNBC's popular primetime programming in full high definition, including the highly rated and critically acclaimed "Countdown with Keith Olbermann," "The Rachel Maddow Show," "Hardball with Chris Matthews," and the smartest morning show on television, "Morning Joe." MSNBC HD is located on DISH Network Ch. 209 in Classic Silver 200 with HD and above, available to customers starting at $22.99 per month for the first six months, along with free installation, a free HD DVR and three months of free premium channels, including HBO and Showtime. For more information about DISH Network, visit www.dishnetwork.com. -

No. 15-7094 September Term, 2016 FILED ON: DECEMBER 9, 2016 MICHAEL QUEEN, APPELLANT

United States Court of Appeals FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT No. 15-7094 September Term, 2016 FILED ON: DECEMBER 9, 2016 MICHAEL QUEEN, APPELLANT v. ED SCHULTZ, APPELLEE Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia (No. 1:11-cv-00871) Before: BROWN and SRINIVASAN, Circuit Judges, and RANDOLPH, Senior Circuit Judge. J U D G M E N T This appeal was considered on the record from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, and briefed and argued by counsel. The Court has accorded the issues full consideration and has determined that they do not warrant a published opinion. See D.C. CIR. R. 36(d). For the reasons stated below, it is ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that the District Court’s May 18, 2015 judgment and August 5, 2015 order be affirmed. In January 2008, NBC cameraman Michael Queen met Ed Schultz in the hallways of NBC after Schultz had finished taping a guest appearance on the television program Hardball with Chris Matthews. Queen, a fan of The Ed Schultz Radio Show, approached Schultz about the possibility of working together to develop a program starring Schultz for network television. Hoping to generate interest from media providers in the prospective program, Queen and Schultz soon thereafter began producing a promotional package. Despite Queen’s urgings, however, the parties at no time executed a contractual agreement. Between late 2008 and early 2009, Schultz independently negotiated with Phil Griffin, the President of MSNBC, for the creation of The Ed Show. The show, which ran from 2009 to 2015, did not include Queen in either an employment or a financial capacity.