Leaving the Commonwealth: Explanations from Different Viewpoints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

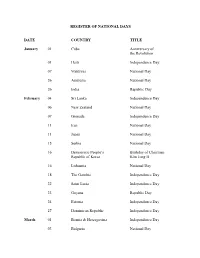

REGISTER of NATIONAL DAYS DATE COUNTRY TITLE January 01

REGISTER OF NATIONAL DAYS DATE COUNTRY TITLE January 01 Cuba Anniversary of the Revolution 01 Haiti Independence Day 07 Maldives National Day 26 Australia National Day 26 India Republic Day February 04 Sri Lanka Independence Day 06 New Zealand National Day 07 Grenada Independence Day 11 Iran National Day 11 Japan National Day 15 Serbia National Day 16 Democratic People’s Birthday of Chairman Republic of Korea Kim Jong II 16 Lithuania National Day 18 The Gambia Independence Day 22 Saint Lucia Independence Day 23 Guyana Republic Day 24 Estonia Independence Day 27 Dominican Republic Independence Day March 01 Bosnia & Herzegovina Independence Day 03 Bulgaria National Day 06 Ghana National Day 12 Mauritius Republic Day 18 Aruba National Day 20 Tunisia National Day 23 Pakistan Pakistan Day 25 Greece Independence Day April 01 Iran National Day 04 Senegal National Day 09 Iraq National Day 16 Kingdom of Birthday of H. M. Denmark The Queen 19 Holy See Anniversary of the Elevation of His Holiness the Pope to the Pontificate 21 United Kingdom Official Birthday of of Great Britain H.M. The Queen 27 South Africa Freedom Day 30 Kingdom of Birthday of H.M. Sweden The King 30 Kingdom of the National Day – Netherlands Queen’s Birthday May 01 Marshall Islands National Day 03 Poland Constitution Day 09 EEC Europe Day 12 Israel National Day 15 Paraguay Independence Day 17 Norway Constitution Day 25 Argentina National Day 26 Georgia Independence Day 26 Guyana Independence Day 28 Armenia National Day 28 Azerbaijan National Day 28 Ethiopia National Day June 02 Italy National Day 05 Kingdom of Constitution Day Denmark 06 Kingdom of Sweden National Day 10 Portugal National Day 12 Philippines National Day 12 Russian Federation National Day 17 Iceland Republic Day 18 Seychelles National Day 23 Luxembourg National Day 24 Sovereign Military Order of Malta St. -

Upcoming Holidays and Observances Weekday Date Holiday Name Countries Where This Is Observed (Might Not Be Complete)

Upcoming holidays and observances Weekday Date Holiday name Countries where this is observed (might not be complete) Tuesday Aug 2 Emancipation Barbados Day observed Tuesday Aug 2 Our Lady of Costa Rica Los Ángeles Tuesday Aug 2 Republic Day Macedonia, Republic of Wednesday Aug 3 The Royal St Canada John's Regatta (Regatta Day) Wednesday Aug 3 Freedom Day Equatorial Guinea Wednesday Aug 3 Martyrs' Day Guinea-Bissau Wednesday Aug 3 Nigerien Niger Independence Day Wednesday Aug 3 Flag´s Day Venezuela Wednesday Aug 3 Election Day South Africa Wednesday Aug 3 Municipal South Africa Elections Wednesday Aug 3 Farmers Day Zambia Thursday Aug 4 Celebrations El Salvador of San Upcoming holidays and observances Weekday Date Holiday name Countries where this is observed (might not be complete) Salvador Thursday Aug 4 National Venezuela Guard´s Day Friday Aug 5 Rio 2016 Brazil Summer Olympics start Friday Aug 5 The Day of Spain Our Lady of Africa Friday Aug 5 Homeland Croatia Thanksgiving Day Friday Aug 5 Celebrations El Salvador of San Salvador Saturday Aug 6 Independence Bolivia Day Saturday Aug 6 Independence Jamaica Day Saturday Aug 6 Celebrations El Salvador of San Salvador Sunday Aug 7 Independence Cote d'Ivoire Day Upcoming holidays and observances Weekday Date Holiday name Countries where this is observed (might not be complete) Sunday Aug 7 Battle of Colombia Boyacá Day Monday Aug 8 Peace Festival Germany Monday Aug 8 Peasants' Day Tanzania Monday Aug 8 Victory Day United States Monday Aug 8 Heroes' Day Zimbabwe Tuesday Aug 9 Double Seven -

Multicultural Tasmania 20 05

multicultural tasmania 20 05 JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH APRIL MAY JUNE JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER 1 Switzerland National Day MON Benin National Day MON 1 Chinese New Year 1 St David’s Day (Wales) 2 Macedonian National Day 1 Antigua and Barbuda Bosnia and Herzegovina National Day TUES Independence Day Tasmanian Craft Fair TUES Korea Independence Deloraine Movement Day Recreation Day (Nth Tas only) 2 2 King Island Show 1 Samoa National Day 3 2 WED WED 3 3 Bulgaria National Day 2 Italy National Day 4 Cook Islands National Day 1 Slovakia Constitution Day 3 1 Romania National Day THUR THUR 4 Sri Lanka Independence 4 1 Islamic Republic Day (Iran) 3 1 Canada Day 5 2 Vietnam Independence Day 4 2 Laos National Day Commemoration Day Burundi National Day United Arab Emirates FRI National Day FRI 5 5 2 1 Marshall Islands 4 Tonga Emancipation Day 2 6 Jamaica National Day 3 Qatar National Day 5 3 National Day Bolivia Independence Day San Marino National SAT Foundation Day SAT 1 New Years Day Bank Holiday 6 Waitangi Day (New Zealand) 6 Ghana Independence Day 3 2 5 Denmark Constitution Day 3 Belarus National Day 7 Côte D’Ivoire National Day 4 1 Burnie Show 6 4 SUN Hobart Summer Festival China National Day SUN Sudan National Day Cyprus National Day Cuba Liberation Day Nigeria Republic Day 2 Hobart Summer Festival 7 7 4 Senegal Independence Day 3 Poland National Day 6 Sweden National Day 4 USA Independence Day 8 5 2 Guinea National Day 7 International Wall of 5 Japan Constitution Rwanda Liberation Day Friendship Anniversary MON Memorial -

National Days 2021

National days Alfabethical order Afghanistan 19 August Georgia 26 May Albania 28 November Germany 3 October Algeria 1 November Ghana 6 March Andorra 8 September Greece 25 March Angola 11 November Grenada 7 February Argentina 25 May Guatemala 15 September Armenia 21 September Guinea 2 October Australia 26 January Guinea-Bissau 24 September Austria 26 October Guyana 23 February Azerbaijan 28 May Haiti 1 January Bahamas 10 July Holy See 13 March Bahrain 16 December Honduras 15 September Bangladesh 26 March Hungary 23 October Barbados 30 November Iceland 17 June Belarus 3 July India 26 January Belgium 21 July Indonesia 17 August Benin 1 August Iran 11 February Bhutan 17 December Iraq 10 December Bolivia 6 August Ireland 17 March Bosnia-Herzegovina 25 November Israel 29 April Botswana 30 September Italy 2 June Brazil 7 September Jamaica 6 August Brunei Darussalam 23 February Japan 23 February Bulgaria 3 March Jordan 25 May Burkina Faso 11 December Kazakhstan 16 December Burundi 1 July Kenya 12 December Cambodia 9 November Korea, D.P.Rep. 9 September Cameroon 20 May Korea, Rep. 3 October Canada 1 July Kosovo 17 February Cape Verde 5 July Kuwait 25 February Central African Republic 1 December Kyrgyzstan 31 August Chad 11 August Laos 2 December Chile 18 September Latvia 18 November China 1 October Lebanon 22 November Colombia 20 July Lesotho 4 October Comoros Islands 6 July Liberia 26 July Congo 15 August Libya 24 December Congo, D.R. 30 June Lithuania 16 February Costa Rica 15 September Luxembourg 23 June Côte d'Ivoire 7 August Madagascar 26 -

G O V E R N M E N T

REPUBLIC OF SRPSKA G O V E R N M E N T Trg Republike Srpske 1, Banja Luka, Tel: 051/339-103, Fax: 051/339-119, E-mail:[email protected] TO ALL AMBASSADORS ACCREDITED TO BIH OPEN LETTER The RS’s Referendum on the January 9 Holiday On 25 September, Republika Srpska will hold a referendum to ascertain its citizens’ views about whether 9 January should be marked and celebrated as the Day of Republika Srpska. The referendum is fully in accord with applicable law and concerns an issue of profound importance to RS citizens. The referendum will inform the RS National Assembly as it considers how to implement the BiH Constitutional Court’s 26 November 2015 decision concerning Republic Day. That decision left to Republika Srpska the authority and responsibility to implement the decision to ensure that the celebration of the Day of Republika Srpska was in harmony with the BiH Constitution. The decision did not forbid Republika Srpska from celebrating the date of its founding. The referendum is fully in accord with applicable law. On 15 July 2016, the RS National Assembly voted, in accordance with the 2010 RS Law on Referendum and Civic Initiative, to hold a referendum asking RS citizens whether Republic Day should continue to be observed on January 9. The RS Constitution has long specifically provided for referenda at Articles 70 and 77. The Council of Europe’s Venice Commission has thoroughly scrutinized the consistency of the RS Constitution with the BiH Constitution,1 and it has never objected to the RS Constitution’s referendum provisions. -

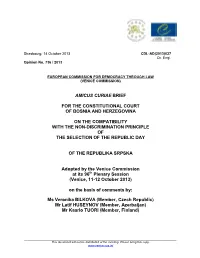

Amicus Curiae Brief

Strasbourg, 14 October 2013 CDL-AD(2013)027 Or. Engl. Opinion No. 736 / 2013 EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF FOR THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA ON THE COMPATIBILITY WITH THE NON-DISCRIMINATION PRINCIPLE OF THE SELECTION OF THE REPUBLIC DAY OF THE REPUBLIKA SRPSKA Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 96th Plenary Session (Venice, 11-12 October 2013) on the basis of comments by: Ms Veronika BILKOVA (Member, Czech Republic) Mr Latif HUSEYNOV (Member, Azerbaijan) Mr Kaarlo TUORI (Member, Finland) _____________________________________________________________________________________________ This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int - 2 - CDL-AD(2013)027 I. Introduction 1. The Venice Commission received a request on 20 June 2013 from the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina (hereinafter BiH) to provide an amicus curiae brief in relation to the review of the constitutionality of Articles 2.(b) and 3.(b) of the Law on Holidays of the Republika Srpska. 2. The specific question asked is ”whether […] the selection of January 9th as the date of the observance of the holiday of the Day of the Republic can result in the discrimination against the members of the Bosniac and Croat people and Others who live in the Republika Srpska, within the meaning of Article 1 of Protocol No. 12 to the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms and Article 1(1) and Article 2(a), (b), (c), (d) of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination”. -

Mehmet Acikalin, Hamide Kilic the Role of Turkish National Holidays in Promoting Character and Citizenship Education

Journal of Social Science Education Volume 16, Number 3, Fall 2017 DOI 10.2390/jsse-v16-i3-1622 Mehmet Acikalin, Hamide Kilic “Turkish nation has a noble character” (M. Kemal Atatürk) The Role of Turkish National Holidays in Promoting Character and Citizenship Education - This paper presents the history and developments of Turkish national holidays including an emerging new national day. - It describes how national holidays celebrated in Turkey and some aspects that emphasize civic virtues within these celebrations. - It discusses several aspects of these national days that may promote character and citizenship education in Turkey. Purpose: This article introduces the history and development of Turkish national holidays. It also describes how these holidays being celebrated overtime in Turkey. Thus, the purpose of this article is providing fundamental information regarding Turkish national holidays and discussing possible role of these holidays in promoting character and citizenship education in Turkey. Design/Methodology/Approach: The article is created based on literature review, document analysis and qualitative observations of the authors with the support of several audiovisual materials that show the celebrations of these national holidays. In order to provide the fundamental information (history, development, and etc.) regarding to the holidays, relevant literature presented and synthesized. Also relevant official documents (laws, regulations, and orders) analyzed. Finally, observations of the authors based on their experiences of these national holidays included in the article with the aid of several audiovisuals materials that provided as hyperlink in the text. Findings: After analyzing all materials described above, we concluded that national holidays in Turkey has some aspects that promote character and citizenship education while these national days may have been lost their spirits and passions comparing their early years. -

Parade in New Delhi, This Letter Initiates the Process of Inviting Tableau Proposals for Participation in the Republic Day Parade 202R

No. 1 (l II)/ 1 / 2020 / D (Cer) Government of India Ministry of Defence Room No.1, South Block, New Delhi, the 2; J July, 2020. To The Chief Election Commissioner of India, Election Commission of India, Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi-O1, The Vice Chairman, Niti Ayog, Niti Ayog/Yojana Bhawan, Sansad Marg, New Delhi-01. Subject: Republic Day Celebrations, 2021 - Selection of Tableaux regarding, S ir, Every year, a select number of tableaux from State Governments/UT Administrations/Central Ministries/Departments participate in the Republic Day Parade in New Delhi, This letter initiates the process of inviting tableau proposals for participation in the Republic Day parade 202r. Relevant guidelines for the purpose are enclosed at Annexure I. It may be noted that participating in the selection/shortlisting process with a proposal for consideration by an Organization will deemed to be the acceptance of the Guidelines by the said proposing entity, 2, Selection process of tableaux is an elaborate and time-consuming exercise, Ir4inistry of Defence constitutes a Committee of distinguished persons drawn from various fields of the arts to help in shortlisting the best proposals. This necessitates that the selection process commences well in advance. 3. In view of the time-constraints, this Ministry will be able to include only a limited number of proposais, For encouraging the participants, the best three tableaux are given trophies by this Ministry, 4. willingness of the Commission may be conveyed alongwith weil conceptualized proposals and brief write-ups to this Ministry by 31'tAugust, 2020. Yours faithfully, (Satis?i$in!h) loint Secretary to the Govt. -

Flag of Armenia - Ventiwiki

Flag of Armenia - VentiWiki http://venti.local/trunk/index.php/Flag_of_Armenia Flag of Armenia From VentiWiki Flag of Armenia The national flag of Armenia, the Armenian Tricolour (known in Armenian as եռագույն, erraguyn), consists of three horizontal bands of equal width, red on the top, blue in the middle, and orange on the bottom. The Armenian Supreme Soviet adopted the current flag on August 24, 1990. On June 15, 2006, the Law on the National Flag of Armenia, governing its usage, was passed by the National Assembly of Armenia. Use National flag. Throughout history, there have been many variations of the Proportion 1:2 Armenian flag. In ancient times, Armenian dynasties were Adopted August 24, 1990 represented by different symbolic animals displayed on their Design A horizontal tricolour of red, blue, and orange flags.[1] In the twentieth century, various Soviet flags represented the Armenian nation. Contents 1 Symbolism 2 Design 3 History 3.1 19th century 3.2 Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic 3.3 Democratic Republic of Armenia 3.4 Early Soviet Armenia and the Transcaucasian SFSR 3.5 Armenian SSR 4 Usage 4.1 National flag days 5 Influence 6 See also 7 References 8 External links Symbolism The meanings of the colors have been interpreted in many different ways. For example, red has stood for the blood shed by Armenian soldiers in war, blue for the Armenian sky, and orange represents the fertile lands of Armenia and the workers who work them.[2] 1 of 7 3/26/08 2:14 PM Flag of Armenia - VentiWiki http://venti.local/trunk/index.php/Flag_of_Armenia The official definition of the colors, as stated in the Constitution of the Republic of Armenia, is: Red symbolizes the Armenian Highland, the Armenian people's continued struggle for “ survival, maintenance of the Christian faith, Armenia's independence and freedom. -

National-Days.Pdf

National days Alfabethical order Afghanistan 19 August Finland 6 December Albania 28 November France 14 July Algeria 1 November Gabon 17 August Andorra 8 September Gambia 18 February Angola 11 November Georgia 26 May Argentina 25 May Germany 3 October Armenia 21 September Ghana 6 March Australia 26 January Greece 25 March Austria 26 October Grenada 7 February Azerbaijan 28 May Guatemala 15 September Bahrain 16 December Guinea 2 October Bangladesh 26 March Guinea-Bissau 24 September Barbados 30 November Guyana 23 February Belarus 3 July Haiti 1 January Belgium 21 July Holy See 13 March Benin 1 August Honduras 15 September Bhutan 17 December Hungary 23 October Bolivia 6 August Iceland 17 June Bosnia-Herzegovina 25 November India 26 January Botswana 30 September Indonesia 17 August Brazil 7 September Iran 11 February Brunei Darussalam 23 February Iraq 10 December Bulgaria 3 March Ireland 17 March Burkina Faso 11 December Israel 29 April Burundi 1 July Italy 2 June Cambodia 9 November Jamaica 6 August Cameroon 20 May Japan 23 February Canada 1 July Jordan 25 May Cape Verde 5 July Kazakhstan 16 December Central African Republic 1 December Kenya 12 December Chile 18 September Korea 3 October China 1 October Korea, D.P.R. 9 September Colombia 20 July Kosovo 17 February Comoros Islands 6 July Kuwait 25 February Congo 15 August Kyrgyzstan 31 August Congo, D.R. 30 June Laos 2 December Costa Rica 15 September Latvia 18 November Côte d'Ivoire 7 August Lebanon 22 November Croatia 30 May Lesotho 4 October Cuba 1 January Liberia 26 July Cyprus 1 October -

NATIONAL HOLIDAYS Country Title January 1 Cuba National Day 1 Sudan National Day 26 Australia National Day 26 India Republic Da

NATIONAL HOLIDAYS Country Title 1 Cuba National Day January 1 Sudan National Day 26 Australia National Day 26 India Republic Day 4 Sri Lanka Independence Day February 6 New Zealand National Day 11 Iran National Day 15 Serbia Statehood Day 16 Lithuania Independence Day 17 Kosovo Independence Day 23 Japan National Day 24 Estonia National Day 25 Kuwait Independence Day 3 Bulgaria National Day March 6 Ghana Independence Day 13 Holy See Pontiff’s Day 15 Hungary National Holiday 17 Ireland St. Patrick’s Day 17 Kosovo Independence Day 23 Pakistan Pakistan Day 25 Greece Independence Day 1 Cyprus National Day April 9 Kosovo Constitution Day 16 Denmark Birthday of H.M. Queen Margrethe II 27 Netherlands Official Celebration of King’s Day 3 Poland Constitution Day May 12 Israel Independence Day 17 Norway Constitution Day 21 Montenegro Independence Day 25 Argentina National Holiday 25 Hashemite Kingdom of National Holiday Jordan 26 Georgia Independence Day 28 Azerbaijan National Holiday 30 Croatia Statehood Day 2 Italy National Day 5 Denmark Constitution Day June 6 Sweden National Day 10 Portugal National Day * United Kingdom Her Majesty’s Birthday (the second Saturday in June) 12 Russian Federation National Day 17 Iceland National Holiday 23 Luxembourg National Day 24 SMO of Malta National Day 25 Slovenia Statehood Day 1 Canada Canada day July 1 Ghana Republic Day 4 United States of America Independence Day 6 Malawi National Day 13 Montenegro Statehood Day 14 France National Day 21 Belgium Accession of King Leopold I (1831) 23 Egypt Anniversary of -

India: Killings Mar Republic Day

News Service 14/98 AI INDEX: ASA 20/01/98 26 JANUARY 1998 India: Killings mar Republic Day As killings continue in conflict-ridden parts of India in the run up to today’s Republic Day, Amnesty International is calling for an end to politically motivated killings. Yesterday, unidentified gunmen shot dead 23 civilians in the village of Vandhama, near the town of Ganderbal in Jammu and Kashmir. The victims, all civilians, included four children, nine women and 10 men. The attackers reportedly surrounded the village and opened indiscriminate fire at the civilian villagers, then torched a small Hindu temple and blew up a house. “The use of a day of public importance to score political points by killing, injuring and maiming civilians, including women and children, should be condemned by everyone,”Amnesty International said. State government officials have held armed opposition groups responsible for the killings. However, none of these groups have claimed responsibility and there is no history of communal tension in the area. Shabir Shah, a leader of the All Parties Hurriyat [Freedom] Conference, a confederation of groupings that favour separation of Kashmir from India, stated that the act was carried out by criminals who intended to alienate Hindus from the Kashmiri Muslim majority. To Amnesty International’s knowledge, the state has not initiated an inquiry into the killings. Earlier, on the night of 13 January, 17 Hindus were killed in Kamrup district of the north-eastern state of Assam -- an area not known for communal tension. Unidentified gunmen suspected to be from the Bodo Liberation Tiger Force (BLTF) opened fire, resulting in the death of two children, nine women and six men.