A Computational Analysis of the Role of Depression in Edgar Allan Poe's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Russell Lowell - Poems

Classic Poetry Series James Russell Lowell - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive James Russell Lowell(22 February 1819 – 12 August 1891) James Russell Lowell was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the Fireside Poets, a group of New England writers who were among the first American poets who rivaled the popularity of British poets. These poets usually used conventional forms and meters in their poetry, making them suitable for families entertaining at their fireside. Lowell graduated from Harvard College in 1838, despite his reputation as a troublemaker, and went on to earn a law degree from Harvard Law School. He published his first collection of poetry in 1841 and married Maria White in 1844. He and his wife had several children, though only one survived past childhood. The couple soon became involved in the movement to abolish slavery, with Lowell using poetry to express his anti-slavery views and taking a job in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania as the editor of an abolitionist newspaper. After moving back to Cambridge, Lowell was one of the founders of a journal called The Pioneer, which lasted only three issues. He gained notoriety in 1848 with the publication of A Fable for Critics, a book-length poem satirizing contemporary critics and poets. The same year, he published The Biglow Papers, which increased his fame. He would publish several other poetry collections and essay collections throughout his literary career. Maria White died in 1853, and Lowell accepted a professorship of languages at Harvard in 1854. -

Views and Experiences from a Colonial Past to Their Unfamiliar New Surroundings

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Matthew David Smith Candidate for the Degree: Doctor of Philosophy ____________________________________________ Director Dr. Carla Gardina Pestana _____________________________________________ Reader Dr. Andrew R.L. Cayton _____________________________________________ Reader Dr. Mary Kupiec Cayton ____________________________________________ Reader Dr. Katharine Gillespie ____________________________________________ Dr. Peter Williams Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT "IN THE LAND OF CANAAN:" RELIGIOUS REVIVAL AND REPUBLICAN POLITICS IN EARLY KENTUCKY by Matthew Smith Against the tumult of the American Revolution, the first white settlers in the Ohio Valley imported their religious worldviews and experiences from a colonial past to their unfamiliar new surroundings. Within a generation, they witnessed the Great Revival (circa 1797-1805), a dramatic mass revelation of religion, converting thousands of worshipers to spiritual rebirth while transforming the region's cultural identity. This study focuses on the lives and careers of three prominent Kentucky settlers: Christian revivalists James McGready and Barton Warren Stone, and pioneering newspaper editor John Bradford. All three men occupy points on a religious spectrum, ranging from the secular public faith of civil religion, to the apocalyptic sectarianism of the Great Revival, yet they also overlap in unexpected ways. This study explores how the evangelicalism -

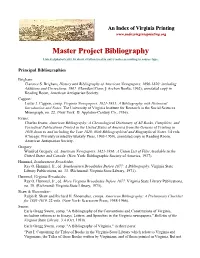

M Master R Proje Ect Bib Bliogr Raphy

An Index of Virginia Printing www.indexvirginiaprinting.org Master Project Bibliography Listed alphabetically by short citation used in entrry notes according to source type. Principal Bibliographies Brigham: Clarence S. Brigham, History and Bibliography of American Newsppapers, 16900-1820: including Additions and Corrections, 1961. (Hamden [Conn.]: Archon Books, 1962); annotated copy in Reading Room, American Antiquarian Society. Cappon: Lester J. Cappon, comp. Virginia Newspapers, 1821-1935: A Biblioggraphy with Historical Introduction and Notes. The University of Virginia Institute for Research in the Social Sciences Monograph, no. 22. (New York: D. Appleton-Century Co., 1936). Evans: Charles Evans, American Bibliography: A Chronological Dictionary of All Books, Pamphlets, and Periodical Publications Printed in the United States of America from the Genesis of Printing in 1639 down to and including the Year 1820: With Bibliographical and Biographical Notes. 14 vols. (Chicago: Privately printed by Blakely Press, 1903-1959), annotated copy in Reading Room, American Antiquarian Society. Gregory: Winifred Gregory, ed. American Newspapers, 1821-1936: A Union List of Files Available in the United States and Canada. (New York: Bibliographic Society of America, 1937). Hummel, Southeastern Broadsides. Ray O. Hummel, Jr., ed. Southeastern Broadsides Before 1877: A Bibliography. Virginia State Library Publications, no. 33. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1971). Hummel, Virginia Broadsides. Ray O. Hummel, Jr., ed. More ViV rginia Broadsides Beforre 1877. Virginia State Library Publications, no. 39. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1975). Shaw & Shoemaker: Ralph R. Shaw and Richard H. Shoemaker, comps. American Bibliography: A Preliminary Checklist for 1801-1819. 22 vols. (New York: Scarecrow Press, 1958-1966). Swem: Earle Gregg Swem, comp. -

Download a PDF Version of the Guide to African American Manuscripts

Guide to African American Manuscripts In the Collection of the Virginia Historical Society A [Abner, C?], letter, 1859. 1 p. Mss2Ab722a1. Written at Charleston, S.C., to E. Kingsland, this letter of 18 November 1859 describes a visit to the slave pens in Richmond. The traveler had stopped there on the way to Charleston from Washington, D.C. He describes in particular the treatment of young African American girls at the slave pen. Accomack County, commissioner of revenue, personal property tax book, ca. 1840. 42 pp. Mss4AC2753a1. Contains a list of residents’ taxable property, including slaves by age groups, horses, cattle, clocks, watches, carriages, buggies, and gigs. Free African Americans are listed separately, and notes about age and occupation sometimes accompany the names. Adams family papers, 1698–1792. 222 items. Mss1Ad198a. Microfilm reels C001 and C321. Primarily the papers of Thomas Adams (1730–1788), merchant of Richmond, Va., and London, Eng. Section 15 contains a letter dated 14 January 1768 from John Mercer to his son James. The writer wanted to send several slaves to James but was delayed because of poor weather conditions. Adams family papers, 1792–1862. 41 items. Mss1Ad198b. Concerns Adams and related Withers family members of the Petersburg area. Section 4 includes an account dated 23 February 1860 of John Thomas, a free African American, with Ursila Ruffin for boarding and nursing services in 1859. Also, contains an 1801 inventory and appraisal of the estate of Baldwin Pearce, including a listing of 14 male and female slaves. Albemarle Parish, Sussex County, register, 1721–1787. 1 vol. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS Philadelphia Libraries. A Survey of Facilities, Needs and Opportunities. A Report to the Carnegie Corporation of New York by The Bibliographical Planning Committee of Philadelphia. (Philadelphia: University of Penn- sylvania Press, 1942. vi, 95 + 46 p. $3.50.) Some explanation is needed of why a technical report of this kind should be reviewed at length in a journal devoted to American history. Two explana- tions can be given: first, this report gives both theoretical and practical con- sideration to improving the tools of scholarly research; second, it has buried away in its statistical tables and it reveals in its final conclusions a very interesting commentary on the history of Philadelphia and on the history of American culture. Any research worker in almost any field, who has at heart the best interests of scholarship, will find this Report worth reading. The complex relationships that are involved in handling the materials of research are here uncovered, analyzed and their costs estimated. Inefficiencies and inadequacies are studied; suggestions are made; the directions that must be taken if improvements are to be effected are indicated. But it is the historical implications that are the chief interest here. Two sets of facts stand out in a marked way, and I quote in both instances the words of the authors of the Report: (1) "We have in the aggregate a magnificent collection of books in this city. We have the material at hand to encourage a great awakening of its intellectual and cultural life." (2) "It is very distressing that Philadelphia, which was the recognized leader of the American library world a century and a half ago, has slipped back into a relatively obscure place, and that its chief library glories are relics of the past, not creations of the present." The significance of these generalizations lies in the difference between them; and the reasons for the existence of this gap throw considerable light on the history of Philadelphia. -

Early American Textbooks, 1775-1900. a Catalog of the Titles Held by the Educational Research Library. INSTITUTION Alvina Treut Burrows Inst., Manhasset, NY

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 264 601 CS 209 572 AUTHOR Svobodny, Dolly, Ed. Early American Textbooks, 1775-1900. A Catalog of the Titles Held by the Educational Research Library. INSTITUTION Alvina Treut Burrows Inst., Manhasset, NY. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 85 CONTRACT 400-78-0015 NOTE 300p.; For companion volumes, see "Fifteenth to Eighteenth Century Rare Books on Education" (ED 139 434) and "Early American Upellers" (CS209 573). Printed on colored paper. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Change; *Educational History; Educational Philosophy; Elementary Secondary Education; Library Cataloas; Publishing Industry; Reference Materials; *Textbooks; *United States History IDENTIFIERS Early American Textbook Collection; Educational Research Library DC ABSTRACT Intended as an educational resource foruse in the study of the early development of education in the UnitedStates, this catalog, prepared by the Educational ResearchLibrary of the U.S. Department of Education's Office of Educational Researchand Improvement, contains bibliographic descriptions formore than 6,000 textbooks published from 1775 to 1900. Followingan introductory essay that discusses the role of textbooks in educational change, the titles are arranged in categories correspondingto the following academic disciplines: (1) art education; (2) business education;(3) civics; (4) English, including children's literature,composition, elocution, grammar, literature, primers, readers, andspellers; (5) foreign languages, including French, German, Greek, Latin,and Spanish; (6) geography; (7) history, including ancient,European, United States (national and local), and world history;(8) mathematics, including algebra, arithmetic, andgeometry; (9) music education; (10) penmanship; (11) philosophy; (12) religious education; (13) science, including anatomy,astronomy, botany, chemistry, geology, nature science, physics, and zoology;and (14) women's education. -

Nathaniel Hawthorne Papers 1843-1862

The Trustees of Reservations – www.thetrustees.org THE TRUSTEES OF RESERVATIONS ARCHIVES & RESEARCH CENTER Guide to Nathaniel Hawthorne Papers 1843-1862 FM.MS.9 by Jane E. Ward Date: May 2019 Archives & Research Center 27 Everett Street, Sharon, MA 02067 www.thetrustees.org [email protected] 781-784-8200 The Trustees of Reservations – www.thetrustees.org Extent: 1 folder Copyright © 2019 The Trustees of Reservations ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION PROVENANCE Transcendental manuscript materials were first acquired by Clara Endicott Sears beginning in 1918 for her Fruitlands Museum in Harvard, Massachusetts. Sears became interested the Transcendentalists after acquiring land in Harvard and restoring the Fruitlands Farmhouse. Materials continued to be collected by the museum throughout the 20th century. In 2016, Fruitlands Museum became The Trustees’ 116th reservation, and these manuscript materials were relocated to the Archives & Research Center in Sharon, Massachusetts. In Harvard, the Fruitlands Museum site continues to display the objects that Sears collected. The museum features four separate collections of significant Shaker, Native American, Transcendentalist, and American art and artifacts. The property features a late 18th century farmhouse that was once home to the writer Louisa May Alcott and her family. Today it is a National Historic Landmark. These papers were acquired through purchase prior to 1936. OWNERSHIP & LITERARY RIGHTS The Nathaniel Hawthorne Papers are the physical property of The Trustees of Reservations. Literary rights, including copyright, belong to the authors or their legal heirs and assigns. CITE AS Nathaniel Hawthorne Papers, Fruitlands Museum. The Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center. RESTRICTIONS ON ACCESS This collection is open for research. Restricted Fragile Material may only be consulted with permission of the archivist. -

Early American Bookbindings from the Collection of Michael Papantonio

Early American Bookbindings From the Collection of Michael Papantonio XHE FOLLOWING LIST of books, noted only in the briefest form, is intended to inform the inquirer of the books in Amer- ican bindings that make up the gifts and bequest from Michael Papantonio to the Society. They form one basis of the AAS collections of American bindings. In addition to these books, Mr. Papantonio gave to the Society nearly two hundred other volumes which he had culled from his bindings collection. Many, if not all of them, have been added to the general collections of AAS. Michael Papantonio was a bookman of acute sensibilities and was possessed of a natural affinity for the bibliographically significant. He honed those abilities through diligent study, hard work, and years of experience. His collection of books in interesting or beautiful American bindings was developed over a number of years as a divertissement. In 1973 he began to give to the Society selected examples from the collection. At his death all but a half dozen of the books in American bindings shelved at his 48th Street apartment in New York, as well as those volumes that he had culled from his collection located in Princeton, came to the Society. Those few that did not join his collection in Worcester included the Confession of Faith of the Boston Synod bound by Ratcliffe, a copy of The Columbiad bound exuberantly by William Swaim, and a presentation copy from the Congress to George Washington of the Acts of Con- gress, 1790. Following his death in 1978, Mr. Papantonio's friends established an endowment, the income from which is 381 382 American Antiquarian Society used to maintain, the collection in good order and make suitable additions to it. -

~Grj(C Chandler Davidson • Professor Emeritus of Sociology

RICE UNIVERSITY Sunbelt Civil Rights: Race, Labor, and Politics in the Fort Worth Aircraft Industry, 1940-1980 by Joseph A. Abel A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITIEE: ~::------.. -... ---.. -•.... Associate Professor of History, Florida International University pJerc:caldwell~f"~ ~GrJ(C Chandler Davidson • Professor Emeritus of Sociology HOUSTON, TEXAS MAY 2011 ABSTRACT Sunbelt Civil Rights: Race, Labor, and Politics in the Aircraft Manufacturing Industry of Texas, 1940-1980 by Joseph Abel This dissertation critically engages the growing literature on the "long" civil rights movement and the African American struggle for equal employment. Focusing on the Fort Worth plants of General Dynamics and its local competitors, this study argues that the federal government's commitment to fair employment can best be understood by examining its attempts to oversee the racial practices of southern defense contractors both prior to and after passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. From World War II onward, the aircraft factories of north Texas became testing grounds for federal civil rights reform as a variety of non-statutory executive agencies attempted to root out employment discrimination. However, although they raised awareness about the problem, these early efforts yielded few results. Because the agencies involved refused to utilize their punitive authority or counter the industry's unstable demand for labor through rational economic planning, workplace inequality continued to be the norm. Ultimately, federal policymakers' reluctance to reform the underlying structural causes of employment discrimination among southern defense contractors set a precedent that has continued to hinder African American economic advancement. -

Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution Through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M. Stampp Series M Selections from the Virginia Historical Society Part 2: Northern Neck of Virginia; also Maryland Associate Editor and Guide Compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Records of ante-bellum southern plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Martin Schipper. Contents: ser. A. Selections from the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina (2 pts.)—[etc.]—ser. L. Selections from the Earl Gregg Swem Library, College of William and Mary—ser. M. Selections from the Virginia Historical Society. 1. Southern States—History—1775–1865—Sources. 2. Slave records—Southern States. 3. Plantation owners—Southern States—Archives. 4. Southern States— Genealogy. 5. Plantation life—Southern States— History—19th century—Sources. I. Stampp, Kenneth M. (Kenneth Milton) II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Schipper, Martin Paul. IV. South Caroliniana Library. V. South Carolina Historical Society. VI. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. VII. Maryland Historical Society. [F213] 975 86-892341 ISBN 1-55655-526-1 (microfilm : ser. M, pt. 2) Compilation © 1995 by Virginia Historical Society. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-526-1. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................................... -

History of the School of Social Work

CHAPTER ONE: THE FIRST THIRTY YEARS Social work education as a degree program at the University of Michigan began in 1921, some 104 years after the university's founding in 1817. This chapter covers social work programs at Michigan from 1921 to 1951. During the first fourteen years of this period a Curriculum in Social Work was offered at the undergraduate level in Ann Arbor in the university's College of Literature, Science, and the Arts. In 1935 the university opened a graduate program for social work in Detroit, where the program leading to a master's degree remained until 1951. In 1951 this graduate program was moved to the Ann Arbor campus, where it has continued its master's program, with the Joint Doctoral Program in Social Work and Social Science initiated in 1957. Part One, Historical Context, presents highlights of the early years of the university as a context for this history of social work education at Michigan, especially in regard to university goals, such as teaching, research, and service. The activities of faculty members at the university who were active prior to 1921 in connecting the fields of economics, philosophy, and sociology to "charity work," philanthropy, social work practice, and social work education are noted. As a historical context, early "training" schools and programs in social work education in the United States are cited. Part Two, Curriculum in Social Work: 1921-35, describes features of the university's program in social work education at the undergraduate level in Ann Arbor from 1921 to 1935. Part Three, Graduate Social Work Programs: 1935-51, covers the graduate program in social work offered by the university in Detroit from 1935 to 1951. -

Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice Report

Slavery and Justice report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice Contents Introduction 3 University Steering Committee Slavery, the Slave Trade, on Slavery and Justice and Brown University 7 Brenda A. Allen Evelyn Hu-DeHart Confronting Historical Injustice: Associate Provost and Professor of History; Director of Institutional Director, Center for the Comparative Perspectives 32 Diversity Study of Race and Ethnicity in America Confronting Slavery’s Legacy: Paul Armstrong The Reparations Question 58 Professor of English Vanessa Huang ’06 A.B., Ethnic Studies Farid Azfar ’03 A.M. Slavery and Justice: Doctoral Candidate, Arlene R. Keizer Concluding Thoughts 80 Department of History Associate Professor of English and American Omer Bartov Recommendations 83 Civilization John P. Birkelund Distinguished Professor Seth Magaziner ’06 Endnotes 88 of European History A.B., History B. Anthony Bogues Marion Orr Image Credits 106 Professor and Chair Fred Lippitt Professor of Africana Studies of Public Policy and Acknowledgments 106 Professor of Political Science James Campbell (Chair) and Urban Studies Associate Professor of American Civilization, Kerry Smith Africana Studies, and Associate Professor of History History and East Asian Studies Ross E. Cheit William Tucker ’04 Associate Professor A.B., Africana Studies of Political Science and and Public Policy Public Policy Michael Vorenberg Steven R. Cornish ’70 A.M. Associate Professor of History Associate Dean of the College Neta C. Crawford ’85 Adjunct Professor, Watson Institute for International Studies Introduction et us begin with a clock. public sites in Providence, including the Esek LIn 2003, Brown University President Ruth J. Hopkins Middle School, Esek Hopkins Park (which Simmons appointed a Steering Committee on includes a statue of him in naval uniform), and Slavery and Justice to investigate and issue a public Admiral Street, where his old house still stands.