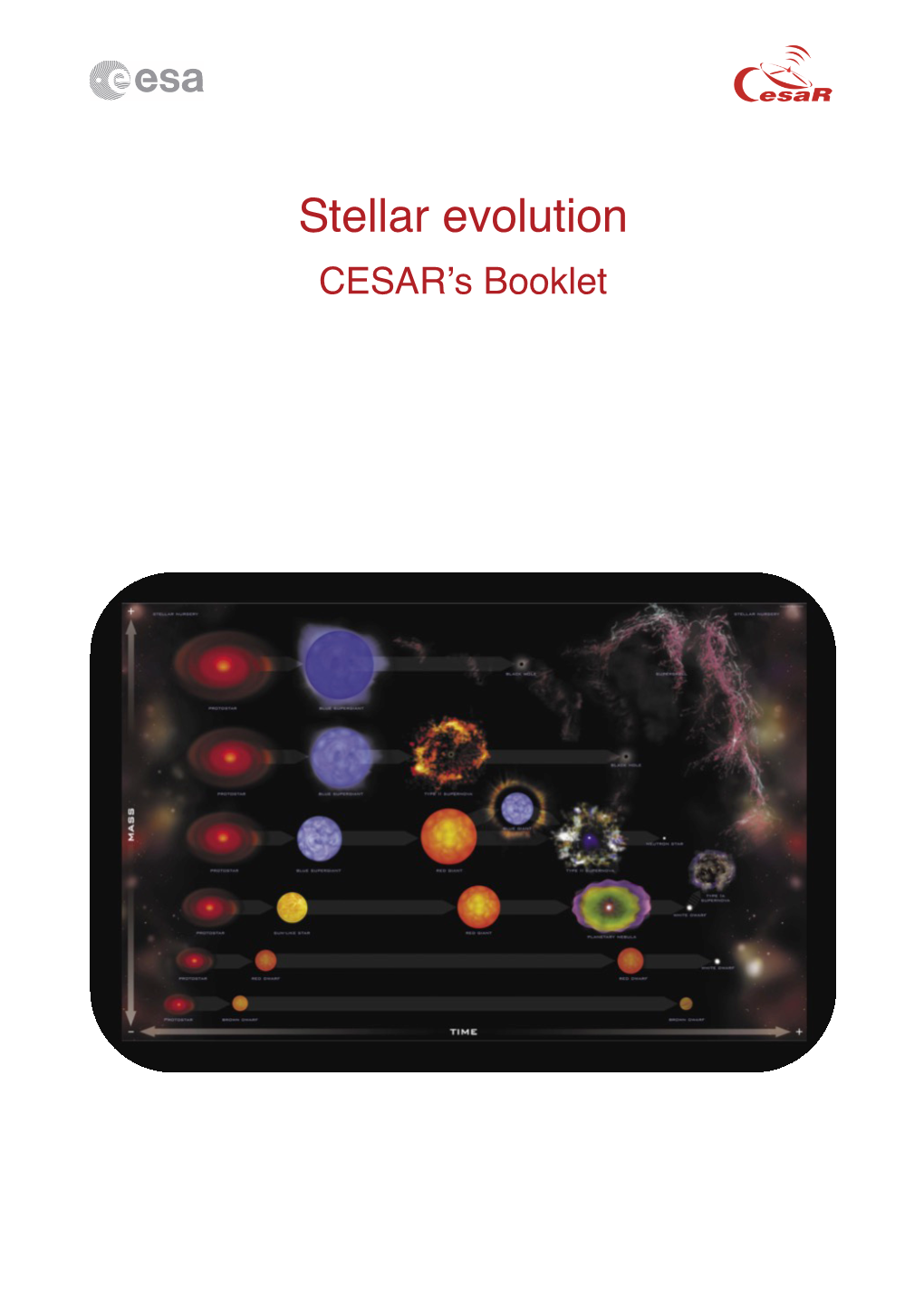

Stellar Evolution CESAR’S Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plasma Physics and Pulsars

Plasma Physics and Pulsars On the evolution of compact o bjects and plasma physics in weak and strong gravitational and electromagnetic fields by Anouk Ehreiser supervised by Axel Jessner, Maria Massi and Li Kejia as part of an internship at the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy, Bonn March 2010 2 This composition was written as part of two internships at the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy in April 2009 at the Radiotelescope in Effelsberg and in February/March 2010 at the Institute in Bonn. I am very grateful for the support, expertise and patience of Axel Jessner, Maria Massi and Li Kejia, who supervised my internship and introduced me to the basic concepts and the current research in the field. Contents I. Life-cycle of stars 1. Formation and inner structure 2. Gravitational collapse and supernova 3. Star remnants II. Properties of Compact Objects 1. White Dwarfs 2. Neutron Stars 3. Black Holes 4. Hypothetical Quark Stars 5. Relativistic Effects III. Plasma Physics 1. Essentials 2. Single Particle Motion in a magnetic field 3. Interaction of plasma flows with magnetic fields – the aurora as an example IV. Pulsars 1. The Discovery of Pulsars 2. Basic Features of Pulsar Signals 3. Theoretical models for the Pulsar Magnetosphere and Emission Mechanism 4. Towards a Dynamical Model of Pulsar Electrodynamics References 3 Plasma Physics and Pulsars I. The life-cycle of stars 1. Formation and inner structure Stars are formed in molecular clouds in the interstellar medium, which consist mostly of molecular hydrogen (primordial elements made a few minutes after the beginning of the universe) and dust. -

Beyond the Solar System Homework for Geology 8

DATE DUE: Name: Ms. Terry J. Boroughs Geology 8 Section: Beyond the Solar System Instructions: Read each question carefully before selecting the BEST answer. Use GEOLOGIC VOCABULARY where APPLICABLE! Provide concise, but detailed answers to essay and fill-in questions. Use an 882-e scantron for your multiple choice and true/false answers. Multiple Choice 1. Which one of the objects listed below has the largest size? A. Galactic clusters. B. Galaxies. C. Stars. D. Nebula. E. Planets. 2. Which one of the objects listed below has the smallest size? A. Galactic clusters. B. Galaxies. C. Stars. D. Nebula. E. Planets. 3. The Sun belongs to this class of stars. A. Black hole C. Black dwarf D. Main-sequence star B. Red giant E. White dwarf 4. The distance to nearby stars can be determined from: A. Fluorescence. D. Stellar parallax. B. Stellar mass. E. Emission nebulae. C. Stellar distances cannot be measured directly 5. Hubble's law states that galaxies are receding from us at a speed that is proportional to their: A. Distance. B. Orientation. C. Galactic position. D. Volume. E. Mass. 6. Our galaxy is called the A. Milky Way galaxy. D. Panorama galaxy. B. Orion galaxy. E. Pleiades galaxy. C. Great Galaxy in Andromeda. 7. The discovery that the universe appears to be expanding led to a widely accepted theory called A. The Big Bang Theory. C. Hubble's Law. D. Solar Nebular Theory B. The Doppler Effect. E. The Seyfert Theory. 8. One of the most common units used to express stellar distances is the A. -

XIII Publications, Presentations

XIII Publications, Presentations 1. Refereed Publications E., Kawamura, A., Nguyen Luong, Q., Sanhueza, P., Kurono, Y.: 2015, The 2014 ALMA Long Baseline Campaign: First Results from Aasi, J., et al. including Fujimoto, M.-K., Hayama, K., Kawamura, High Angular Resolution Observations toward the HL Tau Region, S., Mori, T., Nishida, E., Nishizawa, A.: 2015, Characterization of ApJ, 808, L3. the LIGO detectors during their sixth science run, Classical Quantum ALMA Partnership, et al. including Asaki, Y., Hirota, A., Nakanishi, Gravity, 32, 115012. K., Espada, D., Kameno, S., Sawada, T., Takahashi, S., Ao, Y., Abbott, B. P., et al. including Flaminio, R., LIGO Scientific Hatsukade, B., Matsuda, Y., Iono, D., Kurono, Y.: 2015, The 2014 Collaboration, Virgo Collaboration: 2016, Astrophysical Implications ALMA Long Baseline Campaign: Observations of the Strongly of the Binary Black Hole Merger GW150914, ApJ, 818, L22. Lensed Submillimeter Galaxy HATLAS J090311.6+003906 at z = Abbott, B. P., et al. including Flaminio, R., LIGO Scientific 3.042, ApJ, 808, L4. Collaboration, Virgo Collaboration: 2016, Observation of ALMA Partnership, et al. including Asaki, Y., Hirota, A., Nakanishi, Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger, Phys. Rev. K., Espada, D., Kameno, S., Sawada, T., Takahashi, S., Kurono, Lett., 116, 061102. Y., Tatematsu, K.: 2015, The 2014 ALMA Long Baseline Campaign: Abbott, B. P., et al. including Flaminio, R., LIGO Scientific Observations of Asteroid 3 Juno at 60 Kilometer Resolution, ApJ, Collaboration, Virgo Collaboration: 2016, GW150914: Implications 808, L2. for the Stochastic Gravitational-Wave Background from Binary Black Alonso-Herrero, A., et al. including Imanishi, M.: 2016, A mid-infrared Holes, Phys. -

Luminous Blue Variables

Review Luminous Blue Variables Kerstin Weis 1* and Dominik J. Bomans 1,2,3 1 Astronomical Institute, Faculty for Physics and Astronomy, Ruhr University Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany 2 Department Plasmas with Complex Interactions, Ruhr University Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany 3 Ruhr Astroparticle and Plasma Physics (RAPP) Center, 44801 Bochum, Germany Received: 29 October 2019; Accepted: 18 February 2020; Published: 29 February 2020 Abstract: Luminous Blue Variables are massive evolved stars, here we introduce this outstanding class of objects. Described are the specific characteristics, the evolutionary state and what they are connected to other phases and types of massive stars. Our current knowledge of LBVs is limited by the fact that in comparison to other stellar classes and phases only a few “true” LBVs are known. This results from the lack of a unique, fast and always reliable identification scheme for LBVs. It literally takes time to get a true classification of a LBV. In addition the short duration of the LBV phase makes it even harder to catch and identify a star as LBV. We summarize here what is known so far, give an overview of the LBV population and the list of LBV host galaxies. LBV are clearly an important and still not fully understood phase in the live of (very) massive stars, especially due to the large and time variable mass loss during the LBV phase. We like to emphasize again the problem how to clearly identify LBV and that there are more than just one type of LBVs: The giant eruption LBVs or h Car analogs and the S Dor cycle LBVs. -

SHELL BURNING STARS: Red Giants and Red Supergiants

SHELL BURNING STARS: Red Giants and Red Supergiants There is a large variety of stellar models which have a distinct core – envelope structure. While any main sequence star, or any white dwarf, may be well approximated with a single polytropic model, the stars with the core – envelope structure may be approximated with a composite polytrope: one for the core, another for the envelope, with a very large difference in the “K” constants between the two. This is a consequence of a very large difference in the specific entropies between the core and the envelope. The original reason for the difference is due to a jump in chemical composition. For example, the core may have no hydrogen, and mostly helium, while the envelope may be hydrogen rich. As a result, there is a nuclear burning shell at the bottom of the envelope; hydrogen burning shell in our example. The heat generated in the shell is diffusing out with radiation, and keeps the entropy very high throughout the envelope. The core – envelope structure is most pronounced when the core is degenerate, and its specific entropy near zero. It is supported against its own gravity with the non-thermal pressure of degenerate electron gas, while all stellar luminosity, and all entropy for the envelope, are provided by the shell source. A common property of stars with well developed core – envelope structure is not only a very large jump in specific entropy but also a very large difference in pressure between the center, Pc, the shell, Psh, and the photosphere, Pph. Of course, the two characteristics are closely related to each other. -

A Star Is Born

A STAR IS BORN Overview: Students will research the four stages of the life cycle of a star then further research the ramifications of the stage of the sun on Earth. Objectives: The student will: • research, summarize and illustrate the proper sequence in the life cycle of a star; • share findings with peers; and • investigate Earth’s personal star, the sun, and what will eventually come of it. Targeted Alaska Grade Level Expectations: Science [9] SA1.1 The student demonstrates an understanding of the processes of science by asking questions, predicting, observing, describing, measuring, classifying, making generalizations, inferring, and communicating. [9] SD4.1 The student demonstrates an understanding of the theories regarding the origin and evolution of the universe by recognizing that a star changes over time. [10-11] SA1.1 The student demonstrates an understanding of the processes of science by asking questions, predicting, observing, describing, measuring, classifying, making generalizations, analyzing data, developing models, inferring, and communicating. [10] SD4.1 The student demonstrates an understanding of the theories regarding the origin and evolution of the universe by recognizing phenomena in the universe (i.e., black holes, nebula). [11] SD4.1 The student demonstrates an understanding of the theories regarding the origin and evolution of the universe by describing phenomena in the universe (i.e., black holes, nebula). Vocabulary: black dwarf – the celestial object that remains after a white dwarf has used up all of its -

2. Astrophysical Constants and Parameters

2. Astrophysical constants 1 2. ASTROPHYSICAL CONSTANTS AND PARAMETERS Table 2.1. Revised May 2010 by E. Bergren and D.E. Groom (LBNL). The figures in parentheses after some values give the one standard deviation uncertainties in the last digit(s). Physical constants are from Ref. 1. While every effort has been made to obtain the most accurate current values of the listed quantities, the table does not represent a critical review or adjustment of the constants, and is not intended as a primary reference. The values and uncertainties for the cosmological parameters depend on the exact data sets, priors, and basis parameters used in the fit. Many of the parameters reported in this table are derived parameters or have non-Gaussian likelihoods. The quoted errors may be highly correlated with those of other parameters, so care must be taken in propagating them. Unless otherwise specified, cosmological parameters are best fits of a spatially-flat ΛCDM cosmology with a power-law initial spectrum to 5-year WMAP data alone [2]. For more information see Ref. 3 and the original papers. Quantity Symbol, equation Value Reference, footnote speed of light c 299 792 458 m s−1 exact[4] −11 3 −1 −2 Newtonian gravitational constant GN 6.674 3(7) × 10 m kg s [1] 19 2 Planck mass c/GN 1.220 89(6) × 10 GeV/c [1] −8 =2.176 44(11) × 10 kg 3 −35 Planck length GN /c 1.616 25(8) × 10 m[1] −2 2 standard gravitational acceleration gN 9.806 65 m s ≈ π exact[1] jansky (flux density) Jy 10−26 Wm−2 Hz−1 definition tropical year (equinox to equinox) (2011) yr 31 556 925.2s≈ π × 107 s[5] sidereal year (fixed star to fixed star) (2011) 31 558 149.8s≈ π × 107 s[5] mean sidereal day (2011) (time between vernal equinox transits) 23h 56m 04.s090 53 [5] astronomical unit au, A 149 597 870 700(3) m [6] parsec (1 au/1 arc sec) pc 3.085 677 6 × 1016 m = 3.262 ...ly [7] light year (deprecated unit) ly 0.306 6 .. -

Exors and the Stellar Birthline Mackenzie S

A&A 600, A133 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201630196 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics EXors and the stellar birthline Mackenzie S. L. Moody1 and Steven W. Stahler2 1 Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA e-mail: [email protected] 2 Astronomy Department, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA e-mail: [email protected] Received 6 December 2016 / Accepted 23 February 2017 ABSTRACT We assess the evolutionary status of EXors. These low-mass, pre-main-sequence stars repeatedly undergo sharp luminosity increases, each a year or so in duration. We place into the HR diagram all EXors that have documented quiescent luminosities and effective temperatures, and thus determine their masses and ages. Two alternate sets of pre-main-sequence tracks are used, and yield similar results. Roughly half of EXors are embedded objects, i.e., they appear observationally as Class I or flat-spectrum infrared sources. We find that these are relatively young and are located close to the stellar birthline in the HR diagram. Optically visible EXors, on the other hand, are situated well below the birthline. They have ages of several Myr, typical of classical T Tauri stars. Judging from the limited data at hand, we find no evidence that binarity companions trigger EXor eruptions; this issue merits further investigation. We draw several general conclusions. First, repetitive luminosity outbursts do not occur in all pre-main-sequence stars, and are not in themselves a sign of extreme youth. They persist, along with other signs of activity, in a relatively small subset of these objects. -

Brown Dwarf: White Dwarf: Hertzsprung -Russell Diagram (H-R

Types of Stars Spectral Classifications: Based on the luminosity and effective temperature , the stars are categorized depending upon their positions in the HR diagram. Hertzsprung -Russell Diagram (H-R Diagram) : 1. The H-R Diagram is a graphical tool that astronomers use to classify stars according to their luminosity (i.e. brightness), spectral type, color, temperature and evolutionary stage. 2. HR diagram is a plot of luminosity of stars versus its effective temperature. 3. Most of the stars occupy the region in the diagram along the line called the main sequence. During that stage stars are fusing hydrogen in their cores. Various Types of Stars Brown Dwarf: White Dwarf: Brown dwarfs are sub-stellar objects After a star like the sun exhausts its nuclear that are not massive enough to sustain fuel, it loses its outer layer as a "planetary nuclear fusion processes. nebula" and leaves behind the remnant "white Since, comparatively they are very cold dwarf" core. objects, it is difficult to detect them. Stars with initial masses Now there are ongoing efforts to study M < 8Msun will end as white dwarfs. them in infrared wavelengths. A typical white dwarf is about the size of the This picture shows a brown dwarf around Earth. a star HD3651 located 36Ly away in It is very dense and hot. A spoonful of white constellation of Pisces. dwarf material on Earth would weigh as much as First directly detected Brown Dwarf HD 3651B. few tons. Image by: ESO The image is of Helix nebula towards constellation of Aquarius hosts a White Dwarf Helix Nebula 6500Ly away. -

The Endpoints of Stellar Evolution Answer Depends on the Star’S Mass Star Exhausts Its Nuclear Fuel - Can No Longer Provide Pressure to Support Itself

The endpoints of stellar evolution Answer depends on the star’s mass Star exhausts its nuclear fuel - can no longer provide pressure to support itself. Gravity takes over, it collapses Low mass stars (< 8 Msun or so): End up with ‘white dwarf’ supported by degeneracy pressure. Wide range of structure and composition!!! Answer depends on the star’s mass Star exhausts its nuclear fuel - can no longer provide pressure to support itself. Gravity takes over, it collapses Higher mass stars (8-25 Msun or so): get a ‘neutron star’ supported by neutron degeneracy pressure. Wide variety of observed properties Answer depends on the star’s mass Star exhausts its nuclear fuel - can no longer provide pressure to support itself. Gravity takes over, it collapses Above about 25 Msun: we are left with a ‘black hole’ Black holes are astounding objects because of their simplicity (consider all the complicated physics to set all the macroscopic properties of a star that we have been through) - not unlike macroscopic elementary particles!! According to general relativity, the black hole properties are set by two numbers: mass and spin change of photon energies towards the gravitating mass the opposite when emitted Pound-Rebka experiment used atomic transition of Fe Important physical content for BH studies: general relativity has no intrisic scale instead, all important lengthscales and timescales are set by - and become proportional to the mass. Trick… Examine the energy… Why do we believe that black holes are inevitably created by gravitational collapse? Rather astounding that we go from such complicated initial conditions to such “clean”, simple objects! . -

Lecture 3 - Minimum Mass Model of Solar Nebula

Lecture 3 - Minimum mass model of solar nebula o Topics to be covered: o Composition and condensation o Surface density profile o Minimum mass of solar nebula PY4A01 Solar System Science Minimum Mass Solar Nebula (MMSN) o MMSN is not a nebula, but a protoplanetary disc. Protoplanetary disk Nebula o Gives minimum mass of solid material to build the 8 planets. PY4A01 Solar System Science Minimum mass of the solar nebula o Can make approximation of minimum amount of solar nebula material that must have been present to form planets. Know: 1. Current masses, composition, location and radii of the planets. 2. Cosmic elemental abundances. 3. Condensation temperatures of material. o Given % of material that condenses, can calculate minimum mass of original nebula from which the planets formed. • Figure from Page 115 of “Physics & Chemistry of the Solar System” by Lewis o Steps 1-8: metals & rock, steps 9-13: ices PY4A01 Solar System Science Nebula composition o Assume solar/cosmic abundances: Representative Main nebular Fraction of elements Low-T material nebular mass H, He Gas 98.4 % H2, He C, N, O Volatiles (ices) 1.2 % H2O, CH4, NH3 Si, Mg, Fe Refractories 0.3 % (metals, silicates) PY4A01 Solar System Science Minimum mass for terrestrial planets o Mercury:~5.43 g cm-3 => complete condensation of Fe (~0.285% Mnebula). 0.285% Mnebula = 100 % Mmercury => Mnebula = (100/ 0.285) Mmercury = 350 Mmercury o Venus: ~5.24 g cm-3 => condensation from Fe and silicates (~0.37% Mnebula). =>(100% / 0.37% ) Mvenus = 270 Mvenus o Earth/Mars: 0.43% of material condensed at cooler temperatures. -

The Formation of Brown Dwarfs 459

Whitworth et al.: The Formation of Brown Dwarfs 459 The Formation of Brown Dwarfs: Theory Anthony Whitworth Cardiff University Matthew R. Bate University of Exeter Åke Nordlund University of Copenhagen Bo Reipurth University of Hawaii Hans Zinnecker Astrophysikalisches Institut, Potsdam We review five mechanisms for forming brown dwarfs: (1) turbulent fragmentation of molec- ular clouds, producing very-low-mass prestellar cores by shock compression; (2) collapse and fragmentation of more massive prestellar cores; (3) disk fragmentation; (4) premature ejection of protostellar embryos from their natal cores; and (5) photoerosion of pre-existing cores over- run by HII regions. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. Their relative importance probably depends on environment, and should be judged by their ability to reproduce the brown dwarf IMF, the distribution and kinematics of newly formed brown dwarfs, the binary statis- tics of brown dwarfs, the ability of brown dwarfs to retain disks, and hence their ability to sustain accretion and outflows. This will require more sophisticated numerical modeling than is presently possible, in particular more realistic initial conditions and more realistic treatments of radiation transport, angular momentum transport, and magnetic fields. We discuss the mini- mum mass for brown dwarfs, and how brown dwarfs should be distinguished from planets. 1. INTRODUCTION form a smooth continuum with those of low-mass H-burn- ing stars. Understanding how brown dwarfs form is there- The existence of brown dwarfs was first proposed on the- fore the key to understanding what determines the minimum oretical grounds by Kumar (1963) and Hayashi and Nakano mass for star formation. In section 3 we review the basic (1963).