Postprint Version of Stevenson, Michael. 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking the Participatory Web: a History of Hotwired's “New Publishing Paradigm,” 1994–1997

University of Groningen Rethinking the participatory web Stevenson, Michael Published in: New Media and Society DOI: 10.1177/1461444814555950 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2016 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Stevenson, M. (2016). Rethinking the participatory web: A history of HotWired's 'new publishing paradigm,' 1994-1997. New Media and Society, 18(7), 1331-1346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814555950 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. -

Rethinking the Participatory Web Final

Preprint version of Stevenson, Michael. 2014. “Rethinking the Participatory Web: A History of HotWired’s ‘New Publishing Paradigm,’ 1994–1997.” New Media & Society, October. doi: 10.1177/1461444814555950. Title Rethinking the participatory web: A history of HotWired’s ‘new publishing paradigm,’ 1994-1997. Author Michael Stevenson University of Amsterdam [email protected] Abstract This article critically interrogates key assumptions in popular web discourse by revisiting an early example of web ‘participation.’ Against the claim that Web 2.0 technologies ushered in a new paradigm of participatory media, I turn to the history of HotWired, Wired magazine’s ambitious web-only publication launched in 1994. The case shows how debates about the value of amateur participation vis-à-vis editorial control have long been fundamental to the imagination of the web’s difference from existing media. It also demonstrates how participation may be conceptualized and designed in ways that extend (rather than oppose) 'old media' values like branding and a distinctive editorial voice. In this way, HotWired's history challenges the technology-centric change narrative underlying Web 2.0 in two ways: first, by revealing historical continuity in place of rupture, and, second, showing that 'participation' is not a uniform effect of technology, but rather something constructed within specific social, cultural and economic contexts. Keywords web history, participation, Web 2.0, cyberculture, digital utopianism, Wired !1 Introduction In the mid-2000s, a series of popular accounts celebrating the web’s newfound potential for participatory media appeared, from Kevin Kelly’s (2005) proclamation that active audiences were performing a ‘bottom-up takeover’ of traditional media and Tim O’Reilly’s (2005) definition of ‘Web 2.0’ to Time’s infamous 2006 decision to name ‘You’ as the person of the year (Grossman, 2006). -

Rethinking the Participatory Web Final

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Humanities Commons Preprint version of Stevenson, Michael. 2014. “Rethinking the Participatory Web: A History of HotWired’s ‘New Publishing Paradigm,’ 1994–1997.” New Media & Society, October. doi: 10.1177/1461444814555950. Title Rethinking the participatory web: A history of HotWired’s ‘new publishing paradigm,’ 1994-1997. Author Michael Stevenson University of Amsterdam [email protected] Abstract This article critically interrogates key assumptions in popular web discourse by revisiting an early example of web ‘participation.’ Against the claim that Web 2.0 technologies ushered in a new paradigm of participatory media, I turn to the history of HotWired, Wired magazine’s ambitious web-only publication launched in 1994. The case shows how debates about the value of amateur participation vis-à-vis editorial control have long been fundamental to the imagination of the web’s difference from existing media. It also demonstrates how participation may be conceptualized and designed in ways that extend (rather than oppose) 'old media' values like branding and a distinctive editorial voice. In this way, HotWired's history challenges the technology-centric change narrative underlying Web 2.0 in two ways: first, by revealing historical continuity in place of rupture, and, second, showing that 'participation' is not a uniform effect of technology, but rather something constructed within specific social, cultural and economic contexts. Keywords web history, participation, Web 2.0, cyberculture, digital utopianism, Wired !1 Introduction In the mid-2000s, a series of popular accounts celebrating the web’s newfound potential for participatory media appeared, from Kevin Kelly’s (2005) proclamation that active audiences were performing a ‘bottom-up takeover’ of traditional media and Tim O’Reilly’s (2005) definition of ‘Web 2.0’ to Time’s infamous 2006 decision to name ‘You’ as the person of the year (Grossman, 2006). -

Net Ideologies - Francisco Millarch

Net Ideologies - Francisco Millarch http://www.millarch.org/francisco/papers/net_ideologies.htm By Home : Net Ideologies Francisco Millarch Net Ideologies: London, UK From Cyber-liberalism to Cyber-realism July, 1998 Versions in: [ Spanish ] and [ Italian ] Originally submitted Abstract as a partial requirement for my This paper analyses the over-optimistic ideology propagated by Wired magazine and the various oppositions to it, regarding the role of Internet in shaping our Master Degree in future. By exposing why the cyber-libertarians ideals will not happen and a Hypermedia five-year market hype period is coming to an end, this essay concludes with a Studies more realist perspective of what this revolution is about. at the University of Ideologies, in the outer and inner space Westminster Ideologues, visionaries, or digerati(1)… Never in the human history have so many people laid down their views on what the future will be like. And never were these This paper was also views, prognostics, or ideologies changed, and proven to be wrong, at such fast published by pace. Until recently, the common interpretation of the term ideology was somehow related to a long lasting belief. Capitalism vs. Communism, Left vs. Right, Cybersoc Magazine Libertarians vs. Conservatives and so on… Most of these dichotomies have lasted Issue 4, December for centuries and there is no sign and no need for them to completely converge in 1998 the future. and On 20 July 1969, Neil Alden Armstrong, as commander of the Apollo 11 lunar mission, became the first person to set foot on the moon. Over the following Spark-Online decades both the United States and the former Soviet Union invested billions of dollars in space research having as ultimate goal the protection and promotion of Issue 2, November their ideologies. -

The Political Economy of the Internet1 Korinna Patelis

The Political Economy of the Internet1 Korinna Patelis Dept. of Media and Communications Goldsmiths College University of London June 2000 1 This thesis was supervised by Pr. J. Curran and examined by Pr.C. Levy (internal examiner) and Pr. C. Sparks (external examiner) 1 ABSTRACT This thesis contributes to the critique of and attempts to supersede a dominant approach to the Internet which sees in the Internet the locus of mythical changes and the cure for a number of the ills besetting contemporary society. It does so by presenting and analysing empirical research which situates Internet communication squarely within socio-economic structures. The empirical research presented relocates the Internet within the current wider turn towards commercial expansion in the sphere of communication and the neo-liberal call for the deregulation of media industries. The complexity of the policy frameworks within which this latter is articulated in the US and Europe is examined. The thesis positions Internet communication at the intersection of key capitalist industries, including telecommunications, Internet service provision, on-line content provision and the software industry. Data according to which the pre-existing economic structures prevalent in these industries produce a series of structural inequalities which define Internet communication are presented. It is further argued that such structural inequalities, the boundaries within which on-line communication occurs, are the result of the interlacing of the industries in question, an interlacing defined by the cultural and industrial functions of the industries. In other words, particular industrial and cultural environments are produced by the interplay of these industries - an interplay which the thesis calls signposting. -

A Wired - Impressa E Digital

Escola Superior de Tecnologia de Tomar A WIRED - IMPRESSA E DIGITAL Relatório de Estágio Sara Raquel Machado Pontes Mestrado em Design Editorial Tomar / Junho / 2015 Escola Superior de Tecnologia de Tomar Sara Raquel Machado Pontes A WIRED - IMPRESSA E DIGITAL Relatório de Estágio Orientado por: Drª. Maria João Bom Mendes dos Santos (IPT) Relatório de Estágio apresentado ao Instituto Politécnico de Tomar para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Design Editorial RESUMO O tema abordado neste relatório de estágio é a revista Wired impressa vs. digital. Tendo em conta, que uma das primeiras revistas a ser publicadas para Ipad foi a Wired, um periódico icónico que aborda assuntos referentes à tecnologia, decidi realizar uma análise exaustiva desta revista de forma a relacionar estes dois mundos tão díspares. Para tal, dividi este trabalho em duas partes distintas, sendo a primeira delas divididas em dois capítulos. No primeiro capítulo faz-se uma breve contextualização do universo da impres- são. No segundo capítulo comparam-se os dois universos visuais da Wired, começando por um enquadramento histórico. Na segunda parte faz-se uma breve descrição da empresa na qual foi realizado um estágio curricular, fazendo ainda referência aos trabalhos desenvolvidos durante esse período. Palavras- chaves: Impresso, Digital, iPad, Design Editorial, Revista ABSTRACT The subject of this internship report is Wired printed vs digital magazine. Taking into account, one of the first magazine to be published for Ipad was Wired , one iconic periodic that approach issues related with technology, I decided to perform an exhaustive analysis of this magazine so I can connect these two different worlds. -

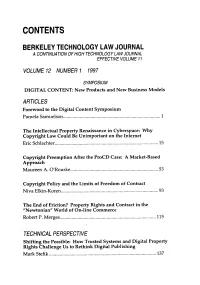

Contents Berkeley Technology Law

CONTENTS BERKELEY TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL A CONTINUATION OF HIGH TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL EFFECTIVE VOLUME 11 VOLUME 12 NUMBER 1 1997 SYMPOSIUM DIGITAL CONTENT: New Products and New Business Models ARTICLES Foreword to the Digital Content Symposium Pam ela Sam uelson ............................................................................ 1 The Intellectual Property Renaissance in Cyberspace: Why Copyright Law Could Be Unimportant on the Internet Eric Schlachter ................................................................................. 15 Copyright Preemption After the ProCD Case: A Market-Based Approach M aureen A . O 'Rourke ..................................................................... 53 Copyright Policy and the Limits of Freedom of Contract N iva Elkin-K oren ............................................................................ 93 The End of Friction? Property Rights and Contract in the "Newtonian" World of On-line Commerce R obert P . M erges ................................................................................ 115 TECHNICAL PERSPECTIVE Shifting the Possible: How Trusted Systems and Digital Property Rights Challenge Us to Rethink Digital Publishing M ark Stefik ......................................................................................... 137 ARTICLES (CONTINUED) Some Reflections on Copyright Management Systems and Laws Designed to Protect Them Ju lie E . C ohen ..................................................................................... 161 Chaos, Cyberspace and Tradition: Legal -

8 Jorn Barger and Dave Winer: Self-Knowledge, Integrity, and Transcendentalism

Weblogs 1994 – 2000: A Genealogy Rudolf Ammann A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Department of Information Studies University College London September 2012 [revised version of 8 May 2013] 2 I, Rudolf Ammann, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated. 3 Abstract Using extensive fieldwork in the online archival record, this thesis ac- counts for the descent and emergence of the weblog as a digital genre during its formative period up to the year 2000. The work examines the weblog’s process of genre formation as diffusion of innovation within a heterogeneous discourse network. It describes this process as a series of several consecutive and cumulative reinterpretations of the emerging genre’s form and intended purpose, effected for the most part by the most central actors in the network. 4 Acknowledgements This work owes a big debt of gratitude to Melissa Terras and Claire Warwick for their expert guidance. At various points, Matthew Kirschenbaum, David Nicholas, Julianne Nyhan and Mike Thelwall provided valuable assistance as well. Anonymous reviewers and delegates of the Hypertext 2009 and the Applications of Social Network Analysis 2010 conferences helped improve some of the materials presented in this thesis. This thesis benefited from correspondence with Jorn Barger, Mark Bernstein, Steve Bogart, Dan Gillmor, the late Chris Gulker, Robert Hooker, Dan Lyke, Pete Prodoehl, Scott Rosenberg, Edward Viel- metti, and Dave Winer, amongst many others. David Kornblith and Frank Bennett promptly and efficiently solved the problems caused by the excessive demands my work placed on Zotero’s citation handling. -

Being Digital

BEING DIGITAL BEING DIGITAL Nicholas Negroponte Hodder & Stoughton Copyright © Nicholas Negroponte 1995 The right of Nicholas Negroponte to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in Great Britain in 1995 by Hodder and Stoughton A division of Hodder Headline PLC Published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 0 340 64525 3 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Mackays of Chatham PLC, Chatham, Kent Hodder and Stoughton A division of Hodder Headline PLC 338 Euston Road London NW1 3BH To Elaine who has put up with my being digital for exactly 11111 years CONTENTS Introduction: The Paradox of a Book 3 Part One: Bits Are Bits 1: The DNA of Information 11 2: Debunking Bandwidth 21 3: Bitcasting 37 4: The Bit Police 51 5: Commingled Bits 62 6: The Bit Business 75 Part Two: Interface 7: Where People and Bits Meet 89 8: Graphical Persona 103 9: 20/20 VR 116 VII 10: Looking and Feeling 127 11: Can We Talk About This? 137 12: Less Is More 149 Part Three: Digital Life 13: The Post Information Age 163 14: Prime Time Is My Time 172 15: Good Connections 184 16: Hard Fun 196 17: Digital Fables and Foibles 206 18: The New E-xpressionists 219 Epilogue: An Age of Optimism 227 Acknowledgments 233 Index 237 VIII being digital INTRODUCTION: THE PARADOX OF A BOOK eing dyslexic, 1 don11 like to read. -

Read the Full Paper (PDF)

Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series #D-81, September 2013 RIPTIDE: What Really Happened to the News Business An oral history of the epic collision between journalism and digital technology, 1980 to the present Reported by John Huey, Martin Nisenholtz and Paul Sagan Shorenstein Center Fellows, Spring 2013 With the Nieman Journalism Lab www.digitalriptide.org Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States. Table of Contents 1. PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................... 2 2. INTRODUCTION: RIPTIDE ................................................................................................................. 4 3. PREHISTORY: THE TELETEXT/VIDEOTEX ERA ................................................................................. 10 4. AMERICA GOES ONLINE (or, It’s the PC, stupid!) ........................................................................... 15 5. THE BIG BANG ................................................................................................................................ 23 6. THE ORIGINAL SIN .......................................................................................................................... 35 7. THEN CAME CABLE ......................................................................................................................... 41 8. RETURN OF NEWSPAPERS............................................................................................................. -

Stevenson the Cybercultural Moment and the New Media Field Final

The cybercultural moment and the new media field Author Michael Stevenson University of Amsterdam [email protected] Abstract This article draws on Pierre Bourdieu's field theory to understand the regenerative 'belief in the new' in new media culture and web history. I begin by noting that discursive constructions of the web as disruptive, open and participatory have emerged at various points in the medium's history, and that these discourses are not as neatly tied to economic interests as most new media criticism would suggest. With this in mind, field theory is introduced as a potential framework for understanding this (re)production of a belief in the new as a dynamic of the interplay of cultural and symbolic forms of capital within the new media field. After discussing how Bourdieu's theory might be applied to new media culture in general terms, I turn to a key moment in the emergence of the new media field - the rise of cybercultural magazines Mondo 2000 and Wired in the early 1990s - to illustrate how Bourdieu's theory may be adapted in the study of new media history. Keywords web history, field theory, Mondo 2000, Wired, Web 2.0 !1 Introduction Why did the World Wide Web seem set to revolutionize the media landscape in the early 1990s, years before it was accessible to mainstream audiences? What led to the belief that the web was an 'exceptional' medium, a belief that it would inevitably provide a more participatory, open and transparent alternative to mass media? To what extent is this belief sustained, and how? In the mid-1990s, high-profile CEOs and industry commentators argued that an internet- powered ‘democratization’ was happening whether or not we liked it (Negroponte, 1995; Markoff, 1994). -

Electric Word, July 1990

- eI.ECer'RiC WoRD . ST E P R GHT TH S WAY Editor/ Publishe r Louis Rossetto Invest in EW Contents Art Director Henri Lucas Executive Editor It's always a crap shoot, you never ACCESS GUIDE TO RICHARD SAUL WURMAN by Jonathan Beard 1 7 JulesMarshall Associate Editor knowhowanissue is goingto turnout. For 25 years, RSW has used his reserves ofignorance to help America understand itself JaneSzita Just coordinating all the elements is a Software Editor better. AsJonathan Beard found outwhen he met the author, architect, cartographer, Colin Brace task only slightly less humbling than creative director of a design agency on each coast of the US and chair of this year's . Editor-at-large Oenise Penrose trying to align all the planets. No epochal TED2 conference, there's plenty more where that came from. SeniorCorrespondent Andrew Joscelyne wonder it's become a standing joke 11ruedeI'Esperance around the EW office: that moment HELP! by Col in Brace 2 3 75013Paris France Tel.+33 (1) 458891 79 each issue when we start laying out When Ford consolidated its worldwide product design and engineering information Correspondents Claude Bedard pages and I get to see the magazine in into one huge online system, it created the world's largest private database. T he 2705RueEd. Montpetit, #11,Montreal, Quebec, its final form for the first time, when I problem: how to get everyone to use it without losing precious production time. The Canada H3T1J6 proclaim in genuine surprise, hey, this solution: create an online help system and interactive training modules. But how to Tel.