0.1 the Spectral Theorem for Hermitian Operators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Math 4571 (Advanced Linear Algebra) Lecture #27

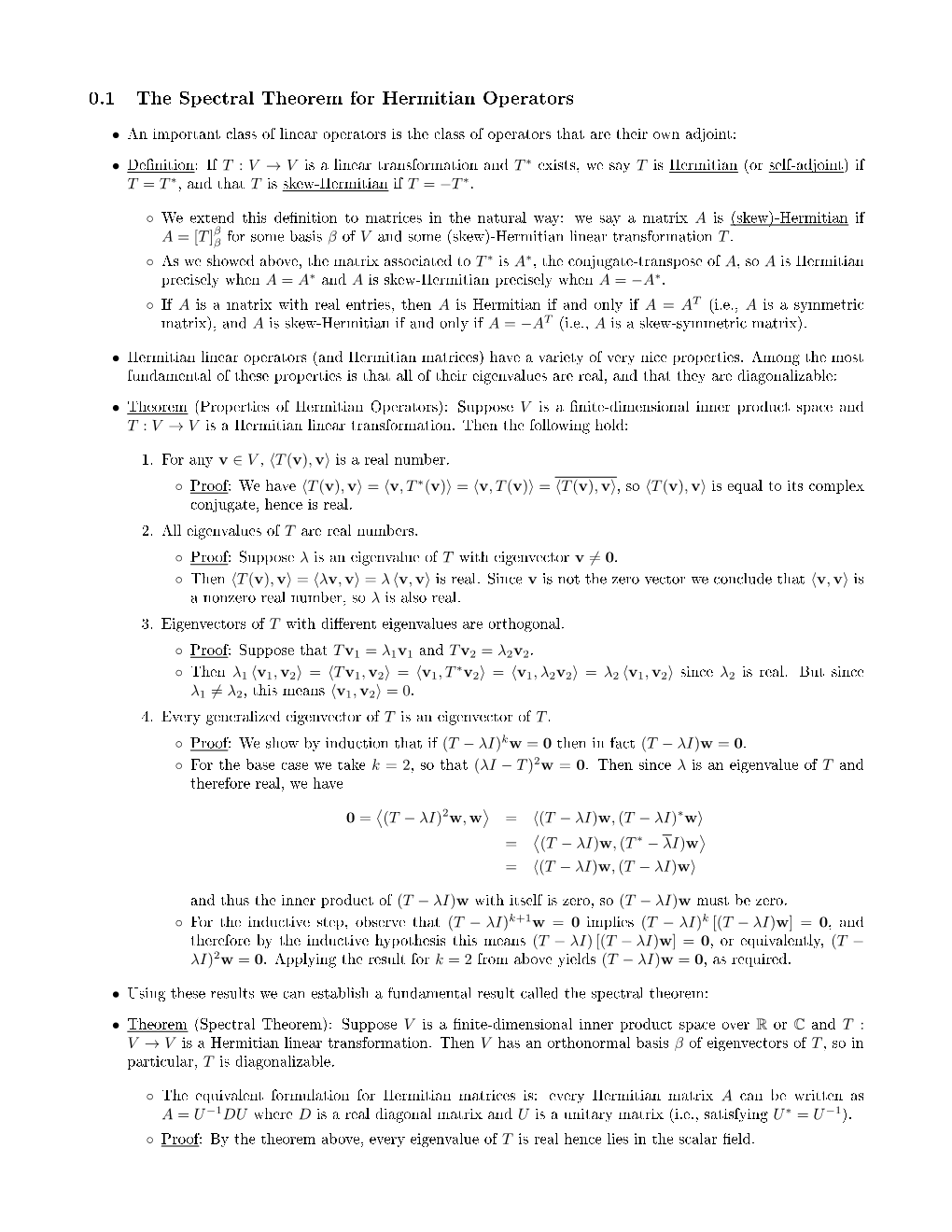

Math 4571 (Advanced Linear Algebra) Lecture #27 Applications of Diagonalization and the Jordan Canonical Form (Part 1): Spectral Mapping and the Cayley-Hamilton Theorem Transition Matrices and Markov Chains The Spectral Theorem for Hermitian Operators This material represents x4.4.1 + x4.4.4 +x4.4.5 from the course notes. Overview In this lecture and the next, we discuss a variety of applications of diagonalization and the Jordan canonical form. This lecture will discuss three essentially unrelated topics: A proof of the Cayley-Hamilton theorem for general matrices Transition matrices and Markov chains, used for modeling iterated changes in systems over time The spectral theorem for Hermitian operators, in which we establish that Hermitian operators (i.e., operators with T ∗ = T ) are diagonalizable In the next lecture, we will discuss another fundamental application: solving systems of linear differential equations. Cayley-Hamilton, I First, we establish the Cayley-Hamilton theorem for arbitrary matrices: Theorem (Cayley-Hamilton) If p(x) is the characteristic polynomial of a matrix A, then p(A) is the zero matrix 0. The same result holds for the characteristic polynomial of a linear operator T : V ! V on a finite-dimensional vector space. Cayley-Hamilton, II Proof: Since the characteristic polynomial of a matrix does not depend on the underlying field of coefficients, we may assume that the characteristic polynomial factors completely over the field (i.e., that all of the eigenvalues of A lie in the field) by replacing the field with its algebraic closure. Then by our results, the Jordan canonical form of A exists. -

Singular Value Decomposition (SVD)

San José State University Math 253: Mathematical Methods for Data Visualization Lecture 5: Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) Dr. Guangliang Chen Outline • Matrix SVD Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) Introduction We have seen that symmetric matrices are always (orthogonally) diagonalizable. That is, for any symmetric matrix A ∈ Rn×n, there exist an orthogonal matrix Q = [q1 ... qn] and a diagonal matrix Λ = diag(λ1, . , λn), both real and square, such that A = QΛQT . We have pointed out that λi’s are the eigenvalues of A and qi’s the corresponding eigenvectors (which are orthogonal to each other and have unit norm). Thus, such a factorization is called the eigendecomposition of A, also called the spectral decomposition of A. What about general rectangular matrices? Dr. Guangliang Chen | Mathematics & Statistics, San José State University3/22 Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) Existence of the SVD for general matrices Theorem: For any matrix X ∈ Rn×d, there exist two orthogonal matrices U ∈ Rn×n, V ∈ Rd×d and a nonnegative, “diagonal” matrix Σ ∈ Rn×d (of the same size as X) such that T Xn×d = Un×nΣn×dVd×d. Remark. This is called the Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) of X: • The diagonals of Σ are called the singular values of X (often sorted in decreasing order). • The columns of U are called the left singular vectors of X. • The columns of V are called the right singular vectors of X. Dr. Guangliang Chen | Mathematics & Statistics, San José State University4/22 Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) * * b * b (n>d) b b b * b = * * = b b b * (n<d) * b * * b b Dr. -

MATH 2370, Practice Problems

MATH 2370, Practice Problems Kiumars Kaveh Problem: Prove that an n × n complex matrix A is diagonalizable if and only if there is a basis consisting of eigenvectors of A. Problem: Let A : V ! W be a one-to-one linear map between two finite dimensional vector spaces V and W . Show that the dual map A0 : W 0 ! V 0 is surjective. Problem: Determine if the curve 2 2 2 f(x; y) 2 R j x + y + xy = 10g is an ellipse or hyperbola or union of two lines. Problem: Show that if a nilpotent matrix is diagonalizable then it is the zero matrix. Problem: Let P be a permutation matrix. Show that P is diagonalizable. Show that if λ is an eigenvalue of P then for some integer m > 0 we have λm = 1 (i.e. λ is an m-th root of unity). Hint: Note that P m = I for some integer m > 0. Problem: Show that if λ is an eigenvector of an orthogonal matrix A then jλj = 1. n Problem: Take a vector v 2 R and let H be the hyperplane orthogonal n n to v. Let R : R ! R be the reflection with respect to a hyperplane H. Prove that R is a diagonalizable linear map. Problem: Prove that if λ1; λ2 are distinct eigenvalues of a complex matrix A then the intersection of the generalized eigenspaces Eλ1 and Eλ2 is zero (this is part of the Spectral Theorem). 1 Problem: Let H = (hij) be a 2 × 2 Hermitian matrix. Use the Min- imax Principle to show that if λ1 ≤ λ2 are the eigenvalues of H then λ1 ≤ h11 ≤ λ2. -

Notes on the Spectral Theorem

Math 108b: Notes on the Spectral Theorem From section 6.3, we know that every linear operator T on a finite dimensional inner prod- uct space V has an adjoint. (T ∗ is defined as the unique linear operator on V such that hT (x), yi = hx, T ∗(y)i for every x, y ∈ V – see Theroems 6.8 and 6.9.) When V is infinite dimensional, the adjoint T ∗ may or may not exist. One useful fact (Theorem 6.10) is that if β is an orthonormal basis for a finite dimen- ∗ ∗ sional inner product space V , then [T ]β = [T ]β. That is, the matrix representation of the operator T ∗ is equal to the complex conjugate of the matrix representation for T . For a general vector space V , and a linear operator T , we have already asked the ques- tion “when is there a basis of V consisting only of eigenvectors of T ?” – this is exactly when T is diagonalizable. Now, for an inner product space V , we know how to check whether vec- tors are orthogonal, and we know how to define the norms of vectors, so we can ask “when is there an orthonormal basis of V consisting only of eigenvectors of T ?” Clearly, if there is such a basis, T is diagonalizable – and moreover, eigenvectors with distinct eigenvalues must be orthogonal. Definitions Let V be an inner product space. Let T ∈ L(V ). (a) T is normal if T ∗T = TT ∗ (b) T is self-adjoint if T ∗ = T For the next two definitions, assume V is finite-dimensional: Then, (c) T is unitary if F = C and kT (x)k = kxk for every x ∈ V (d) T is orthogonal if F = R and kT (x)k = kxk for every x ∈ V Notes 1. -

Asymptotic Spectral Measures: Between Quantum Theory and E

Asymptotic Spectral Measures: Between Quantum Theory and E-theory Jody Trout Department of Mathematics Dartmouth College Hanover, NH 03755 Email: [email protected] Abstract— We review the relationship between positive of classical observables to the C∗-algebra of quantum operator-valued measures (POVMs) in quantum measurement observables. See the papers [12]–[14] and theB books [15], C∗ E theory and asymptotic morphisms in the -algebra -theory of [16] for more on the connections between operator algebra Connes and Higson. The theory of asymptotic spectral measures, as introduced by Martinez and Trout [1], is integrally related K-theory, E-theory, and quantization. to positive asymptotic morphisms on locally compact spaces In [1], Martinez and Trout showed that there is a fundamen- via an asymptotic Riesz Representation Theorem. Examples tal quantum-E-theory relationship by introducing the concept and applications to quantum physics, including quantum noise of an asymptotic spectral measure (ASM or asymptotic PVM) models, semiclassical limits, pure spin one-half systems and quantum information processing will also be discussed. A~ ~ :Σ ( ) { } ∈(0,1] →B H I. INTRODUCTION associated to a measurable space (X, Σ). (See Definition 4.1.) In the von Neumann Hilbert space model [2] of quantum Roughly, this is a continuous family of POV-measures which mechanics, quantum observables are modeled as self-adjoint are “asymptotically” projective (or quasiprojective) as ~ 0: → operators on the Hilbert space of states of the quantum system. ′ ′ A~(∆ ∆ ) A~(∆)A~(∆ ) 0 as ~ 0 The Spectral Theorem relates this theoretical view of a quan- ∩ − → → tum observable to the more operational one of a projection- for certain measurable sets ∆, ∆′ Σ. -

Math 223 Symmetric and Hermitian Matrices. Richard Anstee an N × N Matrix Q Is Orthogonal If QT = Q−1

Math 223 Symmetric and Hermitian Matrices. Richard Anstee An n × n matrix Q is orthogonal if QT = Q−1. The columns of Q would form an orthonormal basis for Rn. The rows would also form an orthonormal basis for Rn. A matrix A is symmetric if AT = A. Theorem 0.1 Let A be a symmetric n × n matrix of real entries. Then there is an orthogonal matrix Q and a diagonal matrix D so that AQ = QD; i.e. QT AQ = D: Note that the entries of M and D are real. There are various consequences to this result: A symmetric matrix A is diagonalizable A symmetric matrix A has an othonormal basis of eigenvectors. A symmetric matrix A has real eigenvalues. Proof: The proof begins with an appeal to the fundamental theorem of algebra applied to det(A − λI) which asserts that the polynomial factors into linear factors and one of which yields an eigenvalue λ which may not be real. Our second step it to show λ is real. Let x be an eigenvector for λ so that Ax = λx. Again, if λ is not real we must allow for the possibility that x is not a real vector. Let xH = xT denote the conjugate transpose. It applies to matrices as AH = AT . Now xH x ≥ 0 with xH x = 0 if and only if x = 0. We compute xH Ax = xH (λx) = λxH x. Now taking complex conjugates and transpose (xH Ax)H = xH AH x using that (xH )H = x. Then (xH Ax)H = xH Ax = λxH x using AH = A. -

The Spectral Theorem for Self-Adjoint and Unitary Operators Michael Taylor Contents 1. Introduction 2. Functions of a Self-Adjoi

The Spectral Theorem for Self-Adjoint and Unitary Operators Michael Taylor Contents 1. Introduction 2. Functions of a self-adjoint operator 3. Spectral theorem for bounded self-adjoint operators 4. Functions of unitary operators 5. Spectral theorem for unitary operators 6. Alternative approach 7. From Theorem 1.2 to Theorem 1.1 A. Spectral projections B. Unbounded self-adjoint operators C. Von Neumann's mean ergodic theorem 1 2 1. Introduction If H is a Hilbert space, a bounded linear operator A : H ! H (A 2 L(H)) has an adjoint A∗ : H ! H defined by (1.1) (Au; v) = (u; A∗v); u; v 2 H: We say A is self-adjoint if A = A∗. We say U 2 L(H) is unitary if U ∗ = U −1. More generally, if H is another Hilbert space, we say Φ 2 L(H; H) is unitary provided Φ is one-to-one and onto, and (Φu; Φv)H = (u; v)H , for all u; v 2 H. If dim H = n < 1, each self-adjoint A 2 L(H) has the property that H has an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors of A. The same holds for each unitary U 2 L(H). Proofs can be found in xx11{12, Chapter 2, of [T3]. Here, we aim to prove the following infinite dimensional variant of such a result, called the Spectral Theorem. Theorem 1.1. If A 2 L(H) is self-adjoint, there exists a measure space (X; F; µ), a unitary map Φ: H ! L2(X; µ), and a 2 L1(X; µ), such that (1.2) ΦAΦ−1f(x) = a(x)f(x); 8 f 2 L2(X; µ): Here, a is real valued, and kakL1 = kAk. -

![Arxiv:1901.01378V2 [Math-Ph] 8 Apr 2020 Where A(P, Q) Is the Arithmetic Mean of the Vectors P and Q, G(P, Q) Is Their P Geometric Mean, and Tr X Stands for Xi](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1881/arxiv-1901-01378v2-math-ph-8-apr-2020-where-a-p-q-is-the-arithmetic-mean-of-the-vectors-p-and-q-g-p-q-is-their-p-geometric-mean-and-tr-x-stands-for-xi-1011881.webp)

Arxiv:1901.01378V2 [Math-Ph] 8 Apr 2020 Where A(P, Q) Is the Arithmetic Mean of the Vectors P and Q, G(P, Q) Is Their P Geometric Mean, and Tr X Stands for Xi

MATRIX VERSIONS OF THE HELLINGER DISTANCE RAJENDRA BHATIA, STEPHANE GAUBERT, AND TANVI JAIN Abstract. On the space of positive definite matrices we consider dis- tance functions of the form d(A; B) = [trA(A; B) − trG(A; B)]1=2 ; where A(A; B) is the arithmetic mean and G(A; B) is one of the different versions of the geometric mean. When G(A; B) = A1=2B1=2 this distance is kA1=2− 1=2 1=2 1=2 1=2 B k2; and when G(A; B) = (A BA ) it is the Bures-Wasserstein metric. We study two other cases: G(A; B) = A1=2(A−1=2BA−1=2)1=2A1=2; log A+log B the Pusz-Woronowicz geometric mean, and G(A; B) = exp 2 ; the log Euclidean mean. With these choices d(A; B) is no longer a metric, but it turns out that d2(A; B) is a divergence. We establish some (strict) convexity properties of these divergences. We obtain characterisations of barycentres of m positive definite matrices with respect to these distance measures. 1. Introduction Let p and q be two discrete probability distributions; i.e. p = (p1; : : : ; pn) and q = (q1; : : : ; qn) are n -vectors with nonnegative coordinates such that P P pi = qi = 1: The Hellinger distance between p and q is the Euclidean norm of the difference between the square roots of p and q ; i.e. 1=2 1=2 p p hX p p 2i hX X p i d(p; q) = k p− qk2 = ( pi − qi) = (pi + qi) − 2 piqi : (1) This distance and its continuous version, are much used in statistics, where it is customary to take d (p; q) = p1 d(p; q) as the definition of the Hellinger H 2 distance. -

MATRICES WHOSE HERMITIAN PART IS POSITIVE DEFINITE Thesis by Charles Royal Johnson in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements Fo

MATRICES WHOSE HERMITIAN PART IS POSITIVE DEFINITE Thesis by Charles Royal Johnson In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California 1972 (Submitted March 31, 1972) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am most thankful to my adviser Professor Olga Taus sky Todd for the inspiration she gave me during my graduate career as well as the painstaking time and effort she lent to this thesis. I am also particularly grateful to Professor Charles De Prima and Professor Ky Fan for the helpful discussions of my work which I had with them at various times. For their financial support of my graduate tenure I wish to thank the National Science Foundation and Ford Foundation as well as the California Institute of Technology. It has been important to me that Caltech has been a most pleasant place to work. I have enjoyed living with the men of Fleming House for two years, and in the Department of Mathematics the faculty members have always been generous with their time and the secretaries pleasant to work around. iii ABSTRACT We are concerned with the class Iln of n><n complex matrices A for which the Hermitian part H(A) = A2A * is positive definite. Various connections are established with other classes such as the stable, D-stable and dominant diagonal matrices. For instance it is proved that if there exist positive diagonal matrices D, E such that DAE is either row dominant or column dominant and has positive diag onal entries, then there is a positive diagonal F such that FA E Iln. -

7 Spectral Properties of Matrices

7 Spectral Properties of Matrices 7.1 Introduction The existence of directions that are preserved by linear transformations (which are referred to as eigenvectors) has been discovered by L. Euler in his study of movements of rigid bodies. This work was continued by Lagrange, Cauchy, Fourier, and Hermite. The study of eigenvectors and eigenvalues acquired in- creasing significance through its applications in heat propagation and stability theory. Later, Hilbert initiated the study of eigenvalue in functional analysis (in the theory of integral operators). He introduced the terms of eigenvalue and eigenvector. The term eigenvalue is a German-English hybrid formed from the German word eigen which means “own” and the English word “value”. It is interesting that Cauchy referred to the same concept as characteristic value and the term characteristic polynomial of a matrix (which we introduce in Definition 7.1) was derived from this naming. We present the notions of geometric and algebraic multiplicities of eigen- values, examine properties of spectra of special matrices, discuss variational characterizations of spectra and the relationships between matrix norms and eigenvalues. We conclude this chapter with a section dedicated to singular values of matrices. 7.2 Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors Let A Cn×n be a square matrix. An eigenpair of A is a pair (λ, x) C (Cn∈ 0 ) such that Ax = λx. We refer to λ is an eigenvalue and to ∈x is× an eigenvector−{ } . The set of eigenvalues of A is the spectrum of A and will be denoted by spec(A). If (λ, x) is an eigenpair of A, the linear system Ax = λx has a non-trivial solution in x. -

Veral Versions of the Spectral Theorem for Normal Operators in Hilbert Spaces

10. The Spectral Theorem The big moment has arrived, and we are now ready to prove se- veral versions of the spectral theorem for normal operators in Hilbert spaces. Throughout this chapter, it should be helpful to compare our results with the more familiar special case when the Hilbert space is finite-dimensional. In this setting, the spectral theorem says that every normal matrix T 2 Cn×n can be diagonalized by a unitary transfor- mation. This can be rephrased as follows: There are numbers zj 2 C n (the eigenvalues) and orthogonal projections Pj 2 B(C ) such that Pm T = j=1 zjPj. The subspaces R(Pj) are orthogonal to each other. From this representation of T , it is then also clear that Pj is the pro- jection onto the eigenspace belonging to zj. In fact, we have already proved one version of the (general) spec- tral theorem: The Gelfand theory of the commutative C∗-algebra A ⊆ B(H) that is generated by a normal operator T 2 B(H) provides a functional calculus: We can define f(T ), for f 2 C(σ(T )) in such a way that the map C(σ(T )) ! A, f 7! f(T ) is an isometric ∗-isomorphism between C∗-algebras, and this is the spectral theorem in one of its ma- ny disguises! See Theorem 9.13 and the discussion that follows. As a warm-up, let us use this material to give a quick proof of the result about normal matrices T 2 Cn×n that was stated above. Consider the C∗-algebra A ⊆ Cn×n that is generated by T . -

Chapter 6 the Singular Value Decomposition Ax=B Version of 11 April 2019

Matrix Methods for Computational Modeling and Data Analytics Virginia Tech Spring 2019 · Mark Embree [email protected] Chapter 6 The Singular Value Decomposition Ax=b version of 11 April 2019 The singular value decomposition (SVD) is among the most important and widely applicable matrix factorizations. It provides a natural way to untangle a matrix into its four fundamental subspaces, and reveals the relative importance of each direction within those subspaces. Thus the singular value decomposition is a vital tool for analyzing data, and it provides a slick way to understand (and prove) many fundamental results in matrix theory. It is the perfect tool for solving least squares problems, and provides the best way to approximate a matrix with one of lower rank. These notes construct the SVD in various forms, then describe a few of its most compelling applications. 6.1 Eigenvalues and eigenvectors of symmetric matrices To derive the singular value decomposition of a general (rectangu- lar) matrix A IR m n, we shall rely on several special properties of 2 ⇥ the square, symmetric matrix ATA. While this course assumes you are well acquainted with eigenvalues and eigenvectors, we will re- call some fundamental concepts, especially pertaining to symmetric matrices. 6.1.1 A passing nod to complex numbers Recall that even if a matrix has real number entries, it could have eigenvalues that are complex numbers; the corresponding eigenvec- tors will also have complex entries. Consider, for example, the matrix 0 1 S = − . " 10# 73 To find the eigenvalues of S, form the characteristic polynomial l 1 det(lI S)=det = l2 + 1.