SCN 74 3&4 Complete.Pdf (449.6Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scandinavian Journal Byzantine Modern Greek

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF BYZANTINE AND MODERN GREEK STUDIES 4 • 2018 JOURNAL OF BYZANTINE SCANDINAVIAN BYZANTINE AND MODERN GREEK STUDIES Barbara Crostini 9 Greek Astronomical Manuscripts: New Perspectives from Swedish Collections Filippo Ronconi 19 Manuscripts as Stratified Social Objects Anne Weddigen 41 Cataloguing Scientific Miscellanies: the Case of Parisinus Graecus 2494 Alberto Bardi 65 Persian Astronomy in the Greek Manuscript Linköping kl. f. 10 Dmitry Afinogenov 89 Hellenistic Jewish texts in George the Monk: Slavonic Testimonies Alexandra Fiotaki & Marika Lekakou 99 The perfective non-past in Modern Greek: a corpus study Yannis Smarnakis 119 Thessaloniki during the Zealots’ Revolt (1342-1350): Power, Political Violence and the Transformation of the Urban Space David Wills 149 “The nobility of the sea and landscape”: John Craxton and Greece 175 Book Reviews ISSN 2002-0007 No 4 • 2018 SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF BYZANTINE AND MODERN GREEK STUDIES Vol. 4 2018 1 We gratefully thank the Ouranis Foundation, Athens for the financial support of the present volume Printed by MediaTryck 2019 Layout: Bengt Pettersson 2 Contents Articles Barbara Crostini Greek Astronomical Manuscripts: New Perspectives from Swedish Collections.........................................9 Filippo Ronconi Manuscripts as Stratified Social Objects..............................................19 Anne Weddigen Cataloguing Scientific Miscellanies: ...................................................41 the Case of Parisinus Graecus 2494 Alberto Bardi Persian Astronomy in the Greek Manuscript Linköping kl. f. 10 ........65 Dmitry Afinogenov Hellenistic Jewish texts in George the Monk: Slavonic Testimonies...89 Alexandra Fiotaki & Marika Lekakou The perfective non-past in Modern Greek: a corpus study...................99 Yannis Smarnakis Thessaloniki during the Zealots’ Revolt (1342-1350): Power, ..........119 Political Violence and the Transformation of the Urban Space. -

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1 The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Pirates' Who's Who Giving Particulars Of The Lives and Deaths Of The Pirates And Buccaneers Author: Philip Gosse Release Date: October 17, 2006 [EBook #19564] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PIRATES' WHO'S WHO *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, Christine D. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Transcriber's note. Many of the names in this book (even outside quoted passages) are inconsistently spelt. I have chosen to retain the original spelling treating these as author error rather than typographical carelessness. THE PIRATES' The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 2 WHO'S WHO Giving Particulars of the Lives & Deaths of the Pirates & Buccaneers BY PHILIP GOSSE ILLUSTRATED BURT FRANKLIN: RESEARCH & SOURCE WORKS SERIES 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science 51 BURT FRANKLIN NEW YORK Published by BURT FRANKLIN 235 East 44th St., New York 10017 Originally Published: 1924 Printed in the U.S.A. Library of Congress Catalog Card No.: 68-56594 Burt Franklin: Research & Source Works Series 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science -

Nikolaos Loukanes's 1526 Iliad and the Unprosodic New Trojans

chapter 11 The Longs and Shorts of an Emergent Nation: Nikolaos Loukanes’s 1526 Iliad and the Unprosodic New Trojans Calliope Dourou According to Milman Parry’s seminal definition, the formula in the Homeric poems is “a group of words which is regularly employed under the same met- rical conditions to express a given essential idea”.1 When analysing, in partic- ular, the intricate set of rules underlying the noun-epithet formulae for the Achaeans,2 the eminent philologist spares no effort in elaborately explaining how phrases such as ἐυκνήμιδας Ἀχαιούς or κάρη κομόωντας Ἀχαιούς are regular- ly employed in the Homeric corpus because they fit the metrical needs of the dactylic hexameter. Perusing, however, Nikolaos Loukanes’s 1526 intriguing ad- aptation of the Iliad and paying close attention to the fixed epithets allotted by him to the Achaeans and the Trojans, we are faced with a distinctly dissimilar system of nomenclature, conditioned primarily not by any prosody-related ex- igencies, but rather by a proto-national sense of pride in the accomplishments of the gallant forefathers and by a concurrent, profound antipathy towards the people that came to be viewed as the New Trojans, the Turks.3 1 Loukanes and His Intellectual and Historical Context Born at the dawn of the eventful sixteenth century, the Cinquecento of the startling transatlantic discoveries, the ceaseless Italian Wars, the vociferous emergence of the Protestant Reformation, and the unrelenting Ottoman ad- vance into European territory, Nikolaos Loukanes, like so many of his erudite compatriots residing in flourishing cities in the West, appears to have ardently 1 Parry (1971: 272). -

When We Now Think of a Pirate's Flag We Think Of

Pirates with Ely Museum Pirate Flags When we now think of a pirate's flag we think of the "Skull and Cross Bones", however many pirates had their own unique designs that in their day would have been well known and would strike fear in the crew of a merchant ship if they saw it. To start with, many pirate ships did not have flags with designs on, instead they used different colour flags to say different things. A plain black flag had been used in the past to show a ship had plague on it and to stay away, so pirates started flying this to cause fear. However it also usually meant that the pirate would accept surrender and spare lives. Others used plain red flags, which dated back to English privateers who used it to show they were not Royal Navy, in pirate use this flag meant no surrender was accepted and no mercy would be shown! Over time pirates started adding their own designs to these plain coloured flags, these unique flags would soon become well known as the pirates reputation increased. Favourite things for pirates to have on their flags were skull, bones or sometimes whole skeletons, all meaning death and aiming to cause fear. They also often used images of swords, daggers and other weapons to show that they were ready to fight. An hourglass would mean that your time is running out as death was coming and a heart was used to show life and death. Jolly Roger Flag A flag would often be made up of one or more of those items and would sometimes include the Captain's initials or a simple outline of a figure depicting the Captain. -

1 BYGONE BELIEFS BEING a SERIES of EXCURSIONS in the BYWAYS of THOUGHT by H. STANLEY REDGROVE Presented By

BYGONE BELIEFS BEING A SERIES OF EXCURSIONS IN THE BYWAYS OF THOUGHT BY H. STANLEY REDGROVE Presented by: www.semantikon.com 1 _Alle Erfahrung ist Magic, und nur magisch erklarbar_. NOVALIS (Friedrich von Hardenberg). Everything possible to be believ'd is an image of truth. WILLIAM BLAKE. 2 TO MY WIFE PREFACE THESE Excursions in the Byways of Thought were undertaken at different times and on different occasions; consequently, the reader may be able to detect in them inequalities of treatment. He may feel that I have lingered too long in some byways and hurried too rapidly through others, taking, as it were, but a general view of the road in the latter case, whilst examining everything that could be seen in the former with, perhaps, undue care. As a matter of fact, how ever, all these excursions have been undertaken with one and the same object in view, that, namely, of understanding aright and appreciating at their true worth some of the more curious byways along which human thought has travelled. It is easy for the superficial thinker to dismiss much of the thought of the past (and, indeed, of the present) as _mere_ superstition, not worth the trouble of investigation: but it is not scientific. There is a reason for every belief, even the most fantastic, and it should be our object to discover this reason. How far, if at all, the reason in any case justifies us in holding a similar belief is, of course, another question. Some of the beliefs I have dealt with I have treated at greater length than others, because it seems to me that the truths of which they are the images-- vague and distorted in many cases though they be--are truths which we have either forgotten nowadays, or are in danger of forgetting. -

Explored Countless Lab- Oratories, Interviewed a Myriad of Scientists, and Prepared Thousands of News Releases, Feature Articles, Web Sites, and Multimedia Packages

Explaining Research This page intentionally left blank Explaining Research How to Reach Key Audiences to Advance Your Work Dennis Meredith 1 2010 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2010 by Dennis Meredith Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Meredith, Dennis. Explaining research : how to reach key audiences to advance your work / Dennis Meredith. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-973205-0 (pbk.) 1. Communication in science. 2. Research. I. Title. Q223.M399 2010 507.2–dc22 2009031328 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper To my mother, Mary Gurvis Meredith. She gave me the words. This page intentionally left blank You do not really understand something unless you can explain it to your grandmother. -

My Research Is Based on a Survey on the Philological and Editorial Activity

My research is based on a survey on the philological and editorial activity, and on the teaching and the historical role played by the humanist Marcus Musurus in the process of spreading the Greek language in the West between the 15th and 16th centuries. This research is fully inserted in the project “Europa Humanistica” which is a European network in which many different European countries participate. This network is promoted by the French Institute IRHT (part of the CNRS) where I have developed my research. The final product of my study is a monograph on Marcus Musurus which completes and enriches the outline of the initial research. I have also produced another monograph about Theocritus of Marcus Musurus and two other articles. The originality of my project lies in the integration of a broad range of interdisciplinary methodologies in order to produce a complete and concise study of the life and work of Musurus. To date only partial studies have been carried out. The following objectives of the project have been achieved. For Philological and historical sector: 1) A global and deepened research on Musurus’ editions which examines : a) assessment of the manuscripts used; b) concrete evaluation of Musurus’ importance to text correction; c) role in the history of the technique of philology and the philological method; d) verification of Musurus’ participation in other editions and, in particular, in the editio princeps of Pindarus (by Z. Calliergi, in Venice in 1513). 2) Study of the notes taken during the lessons (recollectae), and in particular of that one by Cuno and of the notes in the margin to reconstruct the features of Musurus’ teaching activity, and to ascertain its role in the spreading of the knowledge of Greek in Italy and Europe. -

Theodore Levitt's

Quelch.ffirs 4/5/04 4:54 PM Page iii The Global Market Developing a Strategy to Manage Across Borders John Quelch Rohit Deshpande Editors Quelch.ffirs 4/5/04 4:54 PM Page ii Quelch.ffirs 4/5/04 4:54 PM Page i Quelch.ffirs 4/5/04 4:54 PM Page ii Quelch.ffirs 4/5/04 4:54 PM Page iii The Global Market Developing a Strategy to Manage Across Borders John Quelch Rohit Deshpande Editors Quelch.ffirs 4/5/04 4:54 PM Page iv Copyright © 2004 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by Jossey-Bass A Wiley Imprint 989 Market Street, San Francisco, CA 94103-1741 www.josseybass.com No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, e-mail: [email protected]. Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly call our Customer Care Department within the U.S. -

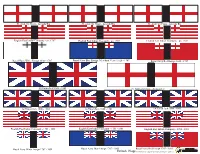

British Flags Permission to Copy for Personal Gaming Use Granted GAME STUDIOS

St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – CrossEnglish - Armada fl ag of the Era Armada Era St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – Cross English - Armada fl ag of the Era Armada Era St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – EnglishCross - flArmada ag of the Era Armada Era EnglishEnglish East IndianIndia Company Company - -pre pre 1707 1707 EnglishEnglish East East Indian India Company - pre 1707 EnglishEnglish EastEast IndianIndia Company Company - - pre pre 1707 1707 Standard Royal Navy Blue Squadron Ensign, Royal Navy White Ensign 1630 - 1707 Royal Navy Blue Ensign /Merchant Vessel 1620 - 1707 RoyalRoyal Navy Navy Red Red Ensign Ensign 1620 1620 - 1707 - 1707 1st Union Jack 1606 - 1801 St. Andrews Cross - Armada Era 1st1st UnionUnion fl Jackag, 1606 1606 - -1801 1801 1st1st Union Union Jack fl ag, 1606 1606 - 1801- 1801 1st1st Union Union fl Jackag, 1606 1606 - -1801 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 Royal Navy White Ensign 1707 - 1801 Royal Navy Blue Ensign 1707 - 1801 RoyalRed Navy Ensign Red as Ensignused by 1707 Royal - 1801Navy and ColonialSEA subjects DOG GAME STUDIOS British Flags Permission to copy for personal gaming use granted GAME STUDIOS . Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands Naval Jack Netherlands Naval Jack Netherlands Naval Jack Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag SEA DOG Dutch Flags GAME STUDIOS Permission to copy for personal gaming use granted. -

Konstantinos Staikos. the Greek Editions of Aldus Manutius and His Greek Collaborators (C

Konstantinos Staikos. The Greek Editions of Aldus Manutius and His Greek Collaborators (c. 1494-1515) Konstantinos Staikos. The Greek Editions of Aldus Manutius and His Greek Collaborators (c. 1494-1515). Trans. Katerina Spathi. New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2016. xv, 293 p., ill. ISBN 9781584563426. US$ 65.00 (hardcover). The recent unveiling of Simon Fraser University’s online resource ALDUS @ SFU: The Wosk- McDonald Aldine Collection allows visitors to examine fully digitized versions of Latin, Greek, and Italian books printed by Manutius Aldus (1452-1515). A contemporary of Gutenberg, Manutius played a significant role in the development of early printing. Konstantinos Staikos’s new volume, The Greek Editions of Aldus Manutius and His Greek Collaborators (c. 1494-1515), provides a visually stunning account of Manutius’s Greek editions that should complement Simon Fraser University’s website by allowing readers a chance to see images from these editions that may otherwise be out of immediate grasp. SHARP News https://www.sharpweb.org/sharpnews/ | 1 Konstantinos Staikos. The Greek Editions of Aldus Manutius and His Greek Collaborators (c. 1494-1515) Manutius was born in Venice at virtually the same historical moment as the Ottoman Turks’ defeat of the Byzantine empire, and although he would not become an active printer until well after the fall of Byzantium, he grew up at a time during which the Latin West intermingled with the Greek East. As Staikos reminds us, knowledge of Greek was an essential part of a humanist education (ix). Staikos seeks in this volume to “honour Aldus’s memory” and remember the role played by Aldus’s “Greek collaborators in this gigantic publishing project” (x); furthermore, he aspires to fill a void in studies of Manutius’s publications that have focused on paratexts, typefaces, and the printing machinery used to create them, but have not yet analyzed them from an aesthetic perspective (xi). -

Pirates and Buccaneers of the Atlantic Coast

ITIG CC \ ',:•:. P ROV Please handle this volume with care. The University of Connecticut Libraries, Storrs Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Lyrasis Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/piratesbuccaneerOOsnow PIRATES AND BUCCANEERS OF THE ATLANTIC COAST BY EDWARD ROWE SNOW AUTHOR OF The Islands of Boston Harbor; The Story of Minofs Light; Storms and Shipwrecks of New England; Romance of Boston Bay THE YANKEE PUBLISHING COMPANY 72 Broad Street Boston, Massachusetts Copyright, 1944 By Edward Rowe Snow No part of this book may be used or quoted without the written permission of the author. FIRST EDITION DECEMBER 1944 Boston Printing Company boston, massachusetts PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN MEMORY OF MY GRANDFATHER CAPTAIN JOSHUA NICKERSON ROWE WHO FOUGHT PIRATES WHILE ON THE CLIPPER SHIP CRYSTAL PALACE PREFACE Reader—here is a volume devoted exclusively to the buccaneers and pirates who infested the shores, bays, and islands of the Atlantic Coast of North America. This is no collection of Old Wives' Tales, half-myth, half-truth, handed down from year to year with the story more distorted with each telling, nor is it a work of fiction. This book is an accurate account of the most outstanding pirates who ever visited the shores of the Atlantic Coast. These are stories of stark realism. None of the arti- ficial school of sheltered existence is included. Except for the extreme profanity, blasphemy, and obscenity in which most pirates were adept, everything has been included which is essential for the reader to get a true and fair picture of the life of a sea-rover. -

Black Markets for Black Labor Pirates, Privateers, and Interlopers in the Early Dispersal of British Slavery

1 Black Markets for Black Labor Pirates, Privateers, and Interlopers in the Early Dispersal of British Slavery Gregory E. O’Malley Caltech Early Modern Group 2014 “The 3d of June [1722], they met with a small New-England Ship, bound home from Barbadoes, which . yielded herself a Prey to the Booters: The Pyrates took out of her fourteen Hogsheads of Rum, six Barrels of Sugar, a large Box of English Goods . , [and] six Negroes, besides a Sum of Money and Plate, and then let her go on her Voyage.” ~Capt. Charles Johnson, General History of the Pyrates1 By the mid-eighteenth century, networks of intercolonial trade would link the many European colonies of the Americas, facilitating a dispersal trade in the enslaved African people arriving from across the Atlantic. But during the early decades of English colonization in the Americas, such regular intercolonial trade circuits lay in the distant future. Instead, in the foundational decades of slavery in English America [ca. 1619-1700], the dispersal of Africans was more 1 Captain Charles Johnson [Daniel Defoe], A General History of the Pyrates, ed. Manuel Schonhorn (Mineola, N.Y., 1999), 314. The current consensus among literary scholars is that Defoe was not actually the author of the General History, but this edition (which attributes authorship to Defoe) is still the best scholarly edition in many regards, including its tracing of primary sources the author used to compile the accounts. Most scholars now accept the interpretation of P. N. Furbank and W. R. Owens that Defoe did not write the book under the pseudonym of Captain Charles Johnson (Furbank and Owens, The Canonisation of Daniel Defoe (New Haven, Conn., 1988) 100-109; see also C.