Histb2016 E.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

書 名 等 発行年 出版社 受賞年 備考 N1 Ueber Das Zustandekommen Der

書 名 等 発行年 出版社 受賞年 備考 Ueber das Zustandekommen der Diphtherie-immunitat und der Tetanus-Immunitat bei thieren / Emil Adolf N1 1890 Georg thieme 1901 von Behring N2 Diphtherie und tetanus immunitaet / Emil Adolf von Behring und Kitasato 19-- [Akitomo Matsuki] 1901 Malarial fever its cause, prevention and treatment containing full details for the use of travellers, University press of N3 1902 1902 sportsmen, soldiers, and residents in malarious places / by Ronald Ross liverpool Ueber die Anwendung von concentrirten chemischen Lichtstrahlen in der Medicin / von Prof. Dr. Niels N4 1899 F.C.W.Vogel 1903 Ryberg Finsen Mit 4 Abbildungen und 2 Tafeln Twenty-five years of objective study of the higher nervous activity (behaviour) of animals / Ivan N5 Petrovitch Pavlov ; translated and edited by W. Horsley Gantt ; with the collaboration of G. Volborth ; and c1928 International Publishing 1904 an introduction by Walter B. Cannon Conditioned reflexes : an investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex / by Ivan Oxford University N6 1927 1904 Petrovitch Pavlov ; translated and edited by G.V. Anrep Press N7 Die Ätiologie und die Bekämpfung der Tuberkulose / Robert Koch ; eingeleitet von M. Kirchner 1912 J.A.Barth 1905 N8 Neue Darstellung vom histologischen Bau des Centralnervensystems / von Santiago Ramón y Cajal 1893 Veit 1906 Traité des fiévres palustres : avec la description des microbes du paludisme / par Charles Louis Alphonse N9 1884 Octave Doin 1907 Laveran N10 Embryologie des Scorpions / von Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov 1870 Wilhelm Engelmann 1908 Immunität bei Infektionskrankheiten / Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov ; einzig autorisierte übersetzung von Julius N11 1902 Gustav Fischer 1908 Meyer Die experimentelle Chemotherapie der Spirillosen : Syphilis, Rückfallfieber, Hühnerspirillose, Frambösie / N12 1910 J.Springer 1908 von Paul Ehrlich und S. -

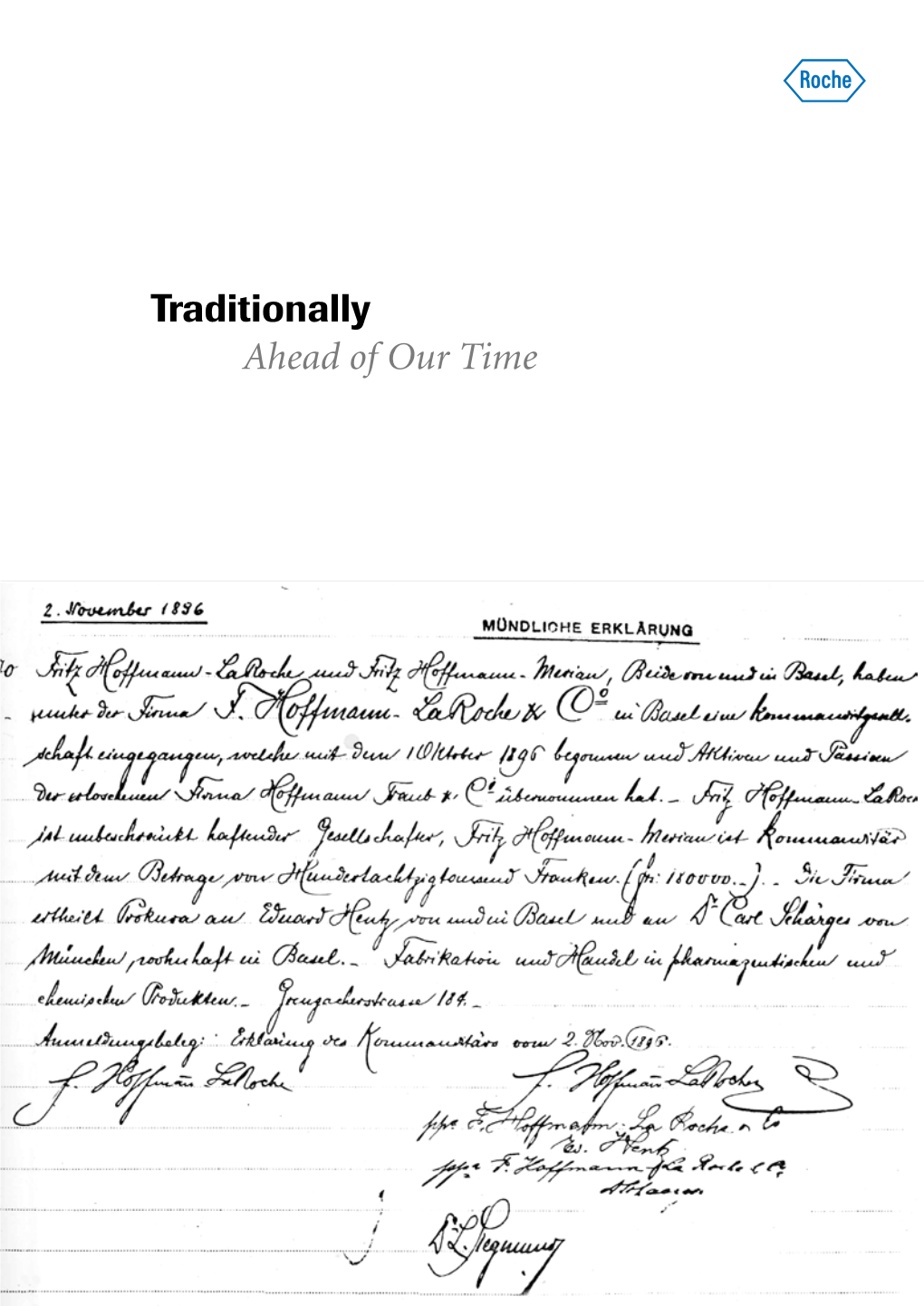

HISTORIA DE Los MEDICAMENTOS

Historia de los Medicamentos HISTORIA DE Los MEDICAMENTOS Alfredo Jácome Roca 2008 Segunda Edición Alfredo Jácome Roca 1 Historia de los Medicamentos Sobre el Autor ALFREDO JACOME ROCA es médico de la Universidad Javeriana de Bogotá, Colombia e Internista-Endocrinólogo de las universidades de Tulane y Hahnemann en los Estados Unidos. Fue profesor de estas materias en la Javeriana y también director médico de Laboratorios Wyeth por cerca de tres décadas. Autor de más de un centenar de artículos científicos, ha escrito varios libros de su especialidad en endocrinología, así como otros relacionados con historia de la medicina. Es Miembro de Número de la Academia Nacional de Medicina, del Colegio Americano de Médicos, de la Sociedad Colombiana de Historia de la Medicina y Miembro Honorario de la Asociación Colombiana de Endocrinología. Su interés por la terapéutica con drogas es el resultado de su ejercicio clínico y de su vinculación a la investigación farmacéutica. La obra “Historia de los Medicamentos” espera cumplir una función didáctica entre profesionales y estudiantes de farmacia o de carreras de la salud y también entre personas de la industria. Actualmente dicta algunas clases sobre este tema para alumnos de medicina de la Universidad de la Sabana. DEDICATORIA A Myriam, Alfredo Luis, Valeria, Daniel; al recuerdo de mis padres. ---------o--------- Alfredo Jácome Roca 2 Historia de los Medicamentos Contenido Prólogo a la Primera Edición Introducción I) La Edad Antigua 1. Los orígenes 2. El papiro de Ebers 3. Shen-Nung, el sanador divino 4. El Ayur-veda 5. El Padre de la Medicina 6. Atenas, Aristóteles, Alejandría 7. -

Benzodiazepine Zu Natur Und Kultur Einer Beliebten Substanzklasse

voll langweilig! Benzodiazepine zu Natur und Kultur einer beliebten Substanzklasse walter heuberger psgn klinik wil FOSUMOS Regionale Gesprächsgruppe St. Gallen März 2018 Inhalt Naturwissenschaft: Pharmakologie Wirkung/Indikationen/KI Benzodiazepinabhängigkeit Mehrfachabhängigkeit Benzodiazepinentzug Substitution Natur Geschichte der Benzodiazepine Was wesensgemäss von selbst da ist Leo Sternbach und der Zufall und sich selbst reproduziert. Kultur im 21. Jahrhundert Kultur Kultur und Benzodiazepine Alles, was der Mensch geschaffen hat, was also nicht naturgegeben ist. voll langweilig! Benzodiazepine FOSUMOS Regionale Gesprächsgruppe St. Gallen März 2018 Pharmakologie der Benzodiazepine voll langweilig! Benzodiazepine FOSUMOS Regionale Gesprächsgruppe St. Gallen März 2018 GABA (Gammaaminobuttersäure) • Wichtigster hemmender Neurotransmitter im Hirn O NH2 HO Relative Häufigkeit von Neuronen nach Neurotransmitter Neuroscience of Clinical Psychiatry Higgins 2007 • Die Aktivierung des GABAA Rezeptors bewirkt durch Chlorideinstrom in die Nervenzelle eine Hyperpolarisation der Zellmembran. • Die Nervenzelle wird so stabilisiert und reagiert weniger schnell. voll langweilig! Benzodiazepine FOSUMOS Regionale Gesprächsgruppe St. Gallen März 2018 Wirkort GABAA Rezeptor Aufbau Proteinkette gefaltet Untereiheit GABAA -Rezeptor GABAA Rezeptor Komplex elektronenmikroskopische Darstellung Nutt BJP 2001 179 Out In (a) (b) Cl – Figure 6.24 Orientation of the GABAA receptor in the membrane. voll langweilig! Benzodiazepine FOSUMOS Regionale Gesprächsgruppe -

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines CRIT program May 2010 Alex Walley, MD, MSc Primary Care Physician HIV Clinic, Boston Medical Center Medical Director, Opioid Treatment Program Boston Public Health Commission Medical Director, Overdose Prevention Pilot Program Massachusetts Department of Public Health CRIT 2010 Learning objectives At the end of this session, participants will be able to: 1. Understand why people use benzodiazepines 2. Know the characteristics of benzodiazepine intoxication and withdrawal syndromes 3. Understand the consequences of these drugs 4. Know the current options for treatment of benzodiazepine dependence CRIT 2010 Roadmap 1. Case and controversies 2. Epidemiology 3. Benzo effects 4. Treatment CRIT 2010 Case • 29 yo man presents for follow-up at methadone clinic after inpatient admission for femur fracture from falling onto subway track from platform. • Treated with clonazepam since age 16 for panic disorder. Takes 6mg in divided doses daily. Missed his afternoon dose day of the accident • Started using heroin at age 23. • On methadone maintenance for 1 year, doing well, about to get his first take home CRIT 2010 Controversies • Are benzodiazepines over-prescribed or under prescribed? • Are they safe in opioid dependent patients? • Why do people buy them off the street? • Why is it so hard to get chronic benzo users off of benzos? CRIT 2010 Why benzos? • Disabling anxiety, insomnia, nausea, seizure disorder • Chronically treated for whom discontinuation is feared • Boosting other sedating medications (opioids) • Euphoria seeking • Self-medication of opioid or alcohol withdrawal or cocaine toxicity CRIT 2010 Prescribers are ambivalent On the one hand On the other hand • Non-medical use of benzos • Rarely the drug of choice very common, esp. -

Protecting Mental Health in the Age of Anxiety: the Context of Valium's Development, Synthesis, and Discovery in the United States, to 1963 Catherine (Cai) E

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2009 Protecting mental health in the Age of Anxiety: The context of Valium's development, synthesis, and discovery in the United States, to 1963 Catherine (cai) E. Guise-richardson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Guise-richardson, Catherine (cai) E., "Protecting mental health in the Age of Anxiety: The onc text of Valium's development, synthesis, and discovery in the United States, to 1963" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 10574. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/10574 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Protecting mental health in the Age of Anxiety: The context of Valium’s development, synthesis, and discovery in the United States, to 1963 by Catherine (Cai) Guise-Richardson A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: History of Technology and Science Program of Study Committee: Hamilton Cravens, Co-Major Professor Alan I Marcus, Co-Major Professor Amy Sue Bix Charles Dobbs David Wilson Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2009 Copyright © Catherine (Cai) Guise-Richardson, 2009. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v CHAPTER 1. -

Leo Sternbach Mogens Schou Roland Kuhn

DURING THE PAST TWO MONTHS THREE MAJOR FIGURES IN THE HISTORY OF PSCHOPHARMACOLOGY PASSED AWAY: LEO STERNBACH MOGENS SCHOU ROLAND KUHN LEO STERNBACH The son of a Polish pharmacist Leo Sternbach was born in Abbazia, Croatia in 1907 He studied pharmacy and chemistry at Jegellonian University, in Cracow, Poland As a postdoctoral student he was involved in developing synthetic dyes and in the course of this process he synthesized several compounds known as HEPTOXDIAZINES, substances with a seven-membered ring After a short academic career at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, he joined Hoffman-La-Roche in Europe After leaving Switzerland for the United States, he continued with Roche. He became Director of Medicinal Chemistry in the Chemical Research Department of Roche in Nutley, New Jersey LEO STERNBACH In the 1940s Sternbach thought that the HEPTOXDIAZINE structure might interact with CNS and stabilized one heptoxdiazine with methyl amine. He named the crystalline powder Ro 5-0690. Reprimanded for pursuing his own project on company time he was told to work on synthesizing potential antibiotics. In the mid-1950s Sternbach in view of the success of Miltown (meprobamate) as a tranquillizer was asked to study the drug and develop something “just different enough to get around the patent.” Reminded of his powder (Ro 5-0690) by a colleague who asked whether it should be thrown away, Sternbach decided to test Ro 5-0690 on mice. In behavioral pharmacological tests Ro 5-0690 was similar to Miltown and different from the barbiturates. Ro 5-0690, or chlordiazepoxide (methaminodiazepoxide) was given the brand name Librium. -

Pharmacologist

A Publication by The American Society for the Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics Pharmacologist Inside: Feature articles from 2016-2017 2018 Special Edition The Pharmacologist is published and distributed by the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. THE PHARMACOLOGIST PRODUCTION TEAM Rich Dodenhoff Catherine L. Fry, PhD Contents Dana Kauffman Judith A. Siuciak, PhD Suzie Thompson Introduction COUNCIL 1 President John D. Schuetz, PhD Ivermectin and River Blindness: The Chip Shot President-Elect 2 Edward T. Morgan, PhD Heard Around the World Past President David R. Sibley, PhD Secretary/Treasurer Taxol: Barking Up the Right Tree John J. Tesmer, PhD 15 Secretary/Treasurer-Elect Margaret E. Gnegy, PhD Chlorpromazine and the Dawn of Past Secretary/Treasurer 27 Charles P. France, PhD Antipsychotics Councilors Wayne L. Backes, PhD Carol L. Beck, PharmD, PhD Cortisone: A Miracle with Flaws Alan V. Smrcka, PhD 40 Chair, Board of Publications Trustees Mary E. Vore, PhD Typhus: War and Deception in 1940’s Poland Chair, Program Committee 52 Michael W. Wood, PhD FASEB Board Representative Brian M. Cox, PhD 61 The Promise and Perils of Pharmacy Executive Officer Compounding Judith A. Siuciak, PhD The Pharmacologist (ISSN 0031-7004) is published quarterly in March, June, Breaking Barriers: The Life and Work of September, and December by the 74 American Society for Pharmacology Rosalyn Yalow and Experimental Therapeutics, 9650 Rockville Pike, Suite E220, Bethesda, MD 20814-3995. Copyright Enbrel: A biotechnology breakthrough © 2018 by the American Society for 86 Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Inc. All rights reserved. If you would like a print subscription to The Pharmacologist, please contact the membership department at [email protected]. -

Początki Molekularnych Nauk O Życiu – Kontekst Polski

Początki molekularnych nauk o życiu – Kontekst Polski STRESZCZENIE 1 iele osiągnięć naukowych oraz dokonań w różnych obszarach nauk o życiu dało Jakub Barciszewski Wpoczątek biologii molekularnej w ubiegłym wieku. Na przełomie wieków Polska formalnie nie istniała, jednakże dla znacznej liczby naukowców funkcjonujących na tych Maciej Szymański2 terenach nie było to ograniczeniem w wytyczaniu nowych szlaków, dokonywaniu funda- mentalnych odkryć czy szkoleniu nowego pokolenia znamienitych ludzi nauki. Chcemy Aleksandra Malesa1 opowiedzieć historię początków biologii molekularnej z polskiej perspektywy, poprzez przybliżenie najważniejszych odkryć naukowców związanych z Polską i jej terytorium. Daria Olszewska1 WPROWADZENIE Wojciech T. Markiewicz1 Na przełomie XIX i XX wieku wydawało się, że człowiek poznał już cały świat. Dzięki podróżom Jamesa Cooka czy Charles Marie de La Condamine Jan Barciszewski1,* wyznaczono dokładne mapy świata, a badania Karola Darwina i Aleksan- dra von Humbolta stały się podstawą do narodzin nowych dziedzin wiedzy, 1Instytut Chemii Bioorganicz- które ogólnie nazywano naukami przyrodniczymi. Mijały lata i kolejne eks- nej Polskiej Akademii Nauk, Poznań pedycje wyruszały by badać znane tereny nowymi metodami oraz szukać 2Wydział Biologii Uniwersytetu im. Adama nowych wyzwań poznawczych. Rów Mariański i Mount Everest wciąż po- Mickiewicza, Poznań zostawały nie zdobyte, o przestworzach nie wspominając. Podobnie działo * się w młodych naukach przyrodniczych, w których rozróżniano już fizykę Instytut Chemii Bioorganicznej Polskiej Akademii Nauk, ul. Noskowskiego 12, 61- chemię, biochemię i biologię. 704 Poznań; e-mail: Jan.Barciszewski@ibch. poznan.pl Wynalezienie mikroskopu przez Antoniego van Leeuwenhoeka i prace Louisa Pasteura pokazały, że aby zrozumieć świat organizmów żywych na- Artykuł otrzymano 17 maja 2018 r. leży spojrzeć w głąb tego świata. Początek XX wieku był okresem w którym Artykuł zaakceptowano 18 maja 2018 r. -

Benzodiazepines Sixty Years Of

A Publication by The American Society for the Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics Pharmacologist Vol. 61 • Number 1 • March 2019 INSIDE 2019 Election Results Sixty Years of 2019 Award Winners Benzodiazepines 2019 Annual Meeting Program The Pharmacologist is published and distributed by the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics THE PHARMACOLOGIST PRODUCTION TEAM Rich Dodenhoff Catherine L. Fry, PhD Contents Tyler Lamb Judith A. Siuciak, PhD Suzie Thompson COUNCIL Message from the President 1 President Edward T. Morgan, PhD President Elect 2019 Election Results 3 Wayne L. Backes, PhD Past President John D. Schuetz, PhD 2019 Award Winners 4 Secretary/Treasurer Margaret E. Gnegy, PhD Secretary/Treasurer Elect 2019 Annual Meeting Program 11 Jin Zhang, PhD Past Secretary/Treasurer John J. Tesmer, PhD Feature Story – Councilors 26 Sixty Years of Benzodiazepines Carol L. Beck, PharmD, PhD Alan V. Smrcka, PhD Kathryn A. Cunningham, PhD Science Policy News Chair, Board of Publications Trustees 38 Mary E. Vore, PhD Chair, Program Committee Education News Michael W. Wood, PhD 42 FASEB Board Representative Brian M. Cox, PhD AMSPC News Executive Office 44 Judith A. Siuciak, PhD Journals News The Pharmacologist (ISSN 0031-7004) 45 is published quarterly in March, June, September, and December by the American Society for Pharmacology Membership News and Experimental Therapeutics, 1801 48 Rockville Pike, Suite 210, Rockville, MD Obituary: Brian Sorrentino 20852-1633. Annual subscription rates: $25.00 for ASPET members; $50.00 for U.S. nonmembers and institutions; Members in the News $75.00 for nonmembers and institutions 52 outside the U.S. Single copy: $25.00. Copyright © 2019 by the American Division News Society for Pharmacology and 54 Experimental Therapeutics Inc. -

Pierwsza Inauguracja Roku Akademickiego W Akademii Lekarskiej W Gdańsku – Wystawa W Bibliotece Głównej

Rok 27 Marzec 2017 nr 3 (315) Pierwsza inauguracja roku akademickiego w Akademii Lekarskiej w Gdańsku – wystawa w Bibliotece Głównej Goście z International Maritime Health Association w IMMiT Przedstawiciele International Maritime Health Association (IMHA): dr Ilona Denisenko, prezydent IMHA, dr Alf Magne Horneland, dy- rektor Norwegian Centre of Maritime Medicine oraz admirał dr Jan Sommerfelt Pettersen, dyrektor Norwegian Association of Maritime Medicine gościli w dniach 23-24 stycznia br. w Instytucie Medycyny Morskiej i Tropikalnej (IMMiT) w Gdyni. Głównym celem wizyty było opracowanie strategii dalszego rozwoju redagowanego w IMMiT kwartalnika International Maritime Health. Czasopismo, wydawane od 1949 r., obecnie jest obserwowane przez Thomson Reuters Web of Science w celu oceny pod kątem przyznania Impact Factor. W czasie wizyty gości z IMHA dr Alf Magne Horneland wygłosił wykład dotyczący funkcjonowania Radia Medico Norway – czołowego ośrodka udzielającego porad medycznych marynarzom na całym świecie. Była to także okazja do spotkania z przedstawicielami Uczelni – prof. Jackiem Bigdą, prorektorem ds. rozwoju i organizacji kształcenia, prof. Przemysławem Rutkowskim, prodziekanem Wydziału Nauk o Zdro- wiu z Oddziałem Pielęgniarstwa i Instytutem Medycyny Morskiej i Tropikalnej oraz pracownikami IMMiT. ■ Styczniowe Młodzieżowe Spotkania z Medycyną za nami Wpływ stresu na układ immunologiczny człowieka to tytuł wykładu, który podczas styczniowych Młodzieżowych Spotkań z Medycyną wygłosiły Kamila Mańkowska i Karolina Spławnik z klasy biologiczno-chemicznej II LO w Sopocie. Zaprezentował się również dr hab. Wacław Nahorski z Instytutu Medycyny Morskiej i Tropikalnej w Gdyni z Historią powstania i działalności szpitala misyjnego w Angoli pod patronatem IMMiT w Gdyni. Konferencja odbyła się 10 stycznia br., tradycyjnie w Atheneum Gedanense Novum. ■ 2 GAZETA AMG 03/2017 W numerze m.in. -

Die Benzodiazepin-Story: Keine Gutenachtgeschichte

Die Benzodiazepin Story (K)eine Gutenachtgeschichte Benzodiazepine - (K)eine Gutenachtgeschichte Walter Heuberger FOSUMOS Regionale Gesprächsgruppe Wil 7.9.2016 Inhalt: Innovation, Hype und Erfahrung Geschichte der Benzodiazepine Pharmakologische Wirkung, Wirkort Indikationen Rechtslage Benzodiazepinabhängigkeit Benzodiazepinentzug Substitution mit Benzodiazepinen Benzodiazepine - (K)eine Gutenachtgeschichte Walter Heuberger FOSUMOS Regionale Gesprächsgruppe Wil 7.9.2016 AUFMERKSAMKEITGipfel der überzogenen Erwartungen Plateau der Produktivität Pfad der Erleuchtung Tal der Enttäuschungen Technologischer Auslöser ZEIT Gartner Hype Cycle Benzodiazepine - (K)eine Gutenachtgeschichte Walter Heuberger FOSUMOS Regionale Gesprächsgruppe Wil 7.9.2016 AUFMERKSAMKEITGipfel der überzogenen Erwartungen z.B. Opiate bei nicht-tumor- bedingten Schmerzen Schweiz Plateau der Produktivität z.B. nüchterner Umgang mit Benzodiazepinen Pfad der Erleuchtung z.B. Opiate bei nicht-tumor- bedingten Schmerzen USA Tal der Enttäuschungen Technologischer Auslöser ZEIT Gartner Hype Cycle Benzodiazepine - (K)eine Gutenachtgeschichte Walter Heuberger FOSUMOS Regionale Gesprächsgruppe Wil 7.9.2016 Benzodiazepine sind sichere, wirksame und hilfreiche Substanzen , wenn ... Benzodiazepine - (K)eine Gutenachtgeschichte Walter Heuberger FOSUMOS Regionale Gesprächsgruppe Wil 7.9.2016 Rationaler Umgang mit Medikamenten • Jede medikamentöse Behandlung setzt eine (selbständige) Abklärung, Diagnose und Indikationsstellung voraus • Patientinnen/Patienten werden über Wirkungen, Nebenwir- -

Unhappy Anniversary: Valium's 40Th Birthday, the Observer, February 2, 2003

20/11/13 benzo.org.uk : Unhappy Anniversary: Valium's 40th Birthday, The Observer, February 2, 2003 « back · www.benzo.org.uk » UNHAPPY ANNIVERSARY VALIUM'S 40TH BIRTHDAY The Observer Sunday, February 2, 2003 by Simon Garfield Forty years ago, Valium was the new wonder pill. Now, with up to a million Britons addicted to tranquillisers, GPs and drug companies are under fire. But as the long battle for compensation is fought out, the suffering continues. Much has changed in Pat Edwards's life in the past 40 years. She has divorced, she has moved from London to the South Coast, she has become a grandmother. But one thing has stayed the same: she is still taking the Valium. Pat Edwards was 25 when she was first prescribed the drug at the end of 1962, a few months before its official launch the following year. She had become unaccountably weepy after the birth of her second child, a condition we may now recognise as post- natal depression. Her local GP in Hackney gave her four days' supply of Valium, a suitably cautious amount for a new treatment, and four days later, after some improvement, Edwards was given another small supply. The drugs seemed to have an immediate effect, and she made plans to return to her job as a hairdresser. But then something else happened. 'One morning I was on my mum's doorstep crying my eyes out. My mother called the doctor, and he didn't come round to see me but upped the dosage of my tablets. They went up from one tablet of five milligrams to two, so I was on 10 milligrams a day.