A Theory to Practice Approach to Reducing the Effects of Hegemonic Masculinity on Gay and Bisexual Inclusion in Menâ•Žs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago Blackhawks Game Notes

Chicago Blackhawks Game Notes Fri, Jan 29, 2021 NHL Game #123 Chicago Blackhawks 2 - 3 - 3 (7 pts) Columbus Blue Jackets 3 - 2 - 3 (9 pts) Team Game: 9 2 - 0 - 0 (Home) Team Game: 9 2 - 0 - 2 (Home) Home Game: 3 0 - 3 - 3 (Road) Road Game: 5 1 - 2 - 1 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 30 Malcolm Subban 2 0 1 1 3.95 .889 70 Joonas Korpisalo 4 1 1 2 2.45 .928 32 Kevin Lankinen 4 2 0 2 2.18 .931 90 Elvis Merzlikins 4 2 1 1 2.94 .906 60 Collin Delia 2 0 2 0 5.00 .863 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 2 D Duncan Keith 8 0 5 5 -2 12 3 D Seth Jones 8 0 1 1 -7 4 5 D Connor Murphy 8 2 3 5 2 0 4 D Scott Harrington - - - - - - 8 L Dominik Kubalik 8 2 3 5 -1 4 8 D Zach Werenski 8 1 1 2 -5 7 13 C Mattias Janmark 8 3 1 4 0 2 9 C Mikko Koivu 2 1 1 2 1 2 16 D Nikita Zadorov 8 0 1 1 0 2 11 C Kevin Stenlund 2 1 1 2 2 0 17 C Dylan Strome 8 2 3 5 -3 4 13 R Cam Atkinson 8 1 2 3 -4 0 22 C Ryan Carpenter 8 1 0 1 0 6 15 D Michael Del Zotto 8 0 4 4 6 0 23 C Philipp Kurashev 7 2 0 2 -2 0 16 C Max Domi 8 1 2 3 -5 4 24 C Pius Suter 8 3 1 4 -4 0 19 C Liam Foudy 8 0 2 2 2 0 34 C Carl Soderberg 3 0 0 0 1 4 20 C Riley Nash 8 0 1 1 2 0 36 C Matthew Highmore 4 0 0 0 0 0 25 C Mikhail Grigorenko 8 1 1 2 -2 2 38 L Brandon Hagel 5 0 1 1 -1 2 28 R Oliver Bjorkstrand 8 2 4 6 -2 19 44 D Calvin de Haan 8 1 1 2 -5 2 38 C Boone Jenner 8 2 3 5 -3 0 46 D Lucas Carlsson 2 0 0 0 0 0 42 C Alexandre Texier 8 4 2 6 -2 6 48 D Wyatt Kalynuk - - - - - - 44 D Vladislav Gavrikov 8 1 0 1 1 2 51 D Ian Mitchell 8 0 1 1 -7 2 46 D Dean Kukan 8 0 3 3 2 0 52 C Reese Johnson - - - - - - 50 L Eric Robinson 8 1 2 3 1 0 53 L Michal Teply - - - - - - 53 D Gabriel Carlsson - - - - - - 54 D Anton Lindholm - - - - - - 58 D David Savard 8 0 2 2 0 4 58 R MacKenzie Entwistle - - - - - - 71 L Nick Foligno 8 3 1 4 0 9 64 C David Kampf 8 0 1 1 -1 8 96 C Jack Roslovic 1 0 0 0 0 0 65 R Andrew Shaw 8 1 2 3 -4 4 73 C Brandon Pirri 1 0 0 0 -2 0 74 D Nicolas Beaudin 1 0 0 0 1 0 88 R Patrick Kane 8 3 4 7 -2 2 Chairman: W. -

Ellies 2018 Finalists Announced

Ellies 2018 Finalists Announced New York, The New Yorker top list of National Magazine Award nominees; CNN’s Don Lemon to host annual awards lunch on March 13 NEW YORK, NY (February 1, 2018)—The American Society of Magazine Editors today published the list of finalists for the 2018 National Magazine Awards for Print and Digital Media. For the fifth year, the finalists were first announced in a 90-minute Twittercast. ASME will celebrate the 53rd presentation of the Ellies when each of the 104 finalists is honored at the annual awards lunch. The 2018 winners will be announced during a lunchtime presentation on Tuesday, March 13, at Cipriani Wall Street in New York. The lunch will be hosted by Don Lemon, the anchor of “CNN Tonight With Don Lemon,” airing weeknights at 10. More than 500 magazine editors and publishers are expected to attend. The winners receive “Ellies,” the elephant-shaped statuettes that give the awards their name. The awards lunch will include the presentation of the Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame Award to the founding editor of Metropolitan Home and Saveur, Dorothy Kalins. Danny Meyer, the chief executive officer of the Union Square Hospitality Group and founder of Shake Shack, will present the Hall of Fame Award to Kalins on behalf of ASME. The 2018 ASME Award for Fiction will also be presented to Michael Ray, the editor of Zoetrope: All-Story. The winners of the 2018 ASME Next Awards for Journalists Under 30 will be honored as well. This year 57 media organizations were nominated in 20 categories, including two new categories, Social Media and Digital Innovation. -

ECF 56 Third Amended Complaint

Case 1:19-cv-00160-RMC Document 56 Filed 09/19/19 Page 1 of 27 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE .DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TAMRYN SPRUTLL and JACOB SUNDSTROM, individually and on behalf of all those similarly situated, Plaintiffs, Civil Action No.: l:l 9-cv-00160-RMC vs. Class Action Complaint VOX MEDIA, INC, Jury Trial Demanded Defendants. THIRD AMENDED COMPLAINT I. INTRODUCTION 1. Plaintiffs Tainryn Spruill and Jacob Sundstrom (together, "Plaintiffs") bring this class and representative action against Defendant Vox Media, Inc., ("Defendant' or "Vox") on behalf of themselves and all other former and current paid content contributors for Vox's sports blogging network. and flagship property SB :Nation in California, who Vox classified as independent contractors. S.B Nation operates over 300 team. sites dedicated to publishing written articles, videos, and other content on professional and college sports. Each team. site posts daily coverage on games, statistics, player trades, and culture. 'The more traffic the team sites attract, the more advertising revenue Vox generates. Vox pays Plaintiffs and similarly situated class members ("Content Contributors") a small monthly stipend to create and edit the written, video, and. audio content on these team sites. Content Contributors' posts are the core of Vox's business. 2. .During the entire class period, Vox. uniformly and consistently misclassfied Content Contributors —including job titles such as Site Manager, Associate Editor, Managing Editor, Deputy Editor, and Contributor — as independent contractors in order to avoid its duties 1 764747.8 Case 1:19-cv-00160-RMC Document 56 Filed 09/19/19 Page 2 of 27 and obligations owed to employees under California law and to gain. -

NHL Playoffs PDF.Xlsx

Anaheim Ducks Boston Bruins POS PLAYER GP G A PTS +/- PIM POS PLAYER GP G A PTS +/- PIM F Ryan Getzlaf 74 15 58 73 7 49 F Brad Marchand 80 39 46 85 18 81 F Ryan Kesler 82 22 36 58 8 83 F David Pastrnak 75 34 36 70 11 34 F Corey Perry 82 19 34 53 2 76 F David Krejci 82 23 31 54 -12 26 F Rickard Rakell 71 33 18 51 10 12 F Patrice Bergeron 79 21 32 53 12 24 F Patrick Eaves~ 79 32 19 51 -2 24 D Torey Krug 81 8 43 51 -10 37 F Jakob Silfverberg 79 23 26 49 10 20 F Ryan Spooner 78 11 28 39 -8 14 D Cam Fowler 80 11 28 39 7 20 F David Backes 74 17 21 38 2 69 F Andrew Cogliano 82 16 19 35 11 26 D Zdeno Chara 75 10 19 29 18 59 F Antoine Vermette 72 9 19 28 -7 42 F Dominic Moore 82 11 14 25 2 44 F Nick Ritchie 77 14 14 28 4 62 F Drew Stafford~ 58 8 13 21 6 24 D Sami Vatanen 71 3 21 24 3 30 F Frank Vatrano 44 10 8 18 -3 14 D Hampus Lindholm 66 6 14 20 13 36 F Riley Nash 81 7 10 17 -1 14 D Josh Manson 82 5 12 17 14 82 D Brandon Carlo 82 6 10 16 9 59 F Ondrej Kase 53 5 10 15 -1 18 F Tim Schaller 59 7 7 14 -6 23 D Kevin Bieksa 81 3 11 14 0 63 F Austin Czarnik 49 5 8 13 -10 12 F Logan Shaw 55 3 7 10 3 10 D Kevan Miller 58 3 10 13 1 50 D Shea Theodore 34 2 7 9 -6 28 D Colin Miller 61 6 7 13 0 55 D Korbinian Holzer 32 2 5 7 0 23 D Adam McQuaid 77 2 8 10 4 71 F Chris Wagner 43 6 1 7 2 6 F Matt Beleskey 49 3 5 8 -10 47 D Brandon Montour 27 2 4 6 11 14 F Noel Acciari 29 2 3 5 3 16 D Clayton Stoner 14 1 2 3 0 28 D John-Michael Liles 36 0 5 5 1 4 F Ryan Garbutt 27 2 1 3 -3 20 F Jimmy Hayes 58 2 3 5 -3 29 F Jared Boll 51 0 3 3 -3 87 F Peter Cehlarik 11 0 2 2 -

How Cities Can Benefit from America's Fastest Growing Workforce Trend

COMMUNITIES AND THE GIG ECONOMY How cities can benefit from America’s fastest growing workforce trend BY PATRICK TUOHEY, LINDSEY ZEA OWEN PARKER AND SCOTT TUTTLE 4700 W. ROCHELLE AVE., SUITE 141, LAS VEGAS, NEVADA | (702) 546-8736 | BETTER-CITIES.ORG ANNUAL REPORT - 2019/20 M I S S I O N Better Cities Project uncovers ideas that work, promotes realistic solutions and forges partnerships that help people in America’s largest cities live free and happy lives. ANNUAL REPORT - 2019/20 BETTER CITIES PROJECT WHAT DOES A NEW CONTENTS WAY OF WORKING 2 MEAN FOR CITIES? INTRODUCTION he gig economy is big and growing — 4 THE STATE OF THE GIG even if there is not yet an agreed-upon ECONOMY T definition of the term. For cities, this offers the prospect of added tax revenue 5 and economic resilience. But often, legacy METHODOLOGY policies hold back gig workers. Given the organic growth in gig work and its function as a safety net 6 for millions of workers impacted by the pandemic, it’s reasonable to AMERICA’S GIG ECONOMY IS expect gig-work growth will continue and even speed up; cities with a IN A TUG OF WAR ACROSS THE NATION permissive regulatory structure may be more insulated from econom- ic chaos. Key areas for city leaders to focus on include: 7 WORKERS LIKE GIG WORK n THE GAP BETWEEN REGULATION AND TECHNOLOGY CAN HOLD CITI- ZENS BACK AND COST SIGNIFICANT TAX REVENUE. Regulation often lags behind technological innovation and, in the worst circumstanc- 9 es, can threaten to snuff it out. -

Tripadvisor Appoints Lindsay Nelson As President of the Company's Core Experience Business Unit

TripAdvisor Appoints Lindsay Nelson as President of the Company's Core Experience Business Unit October 25, 2018 A recognized leader in digital media, new CoreX president will oversee the TripAdvisor brand, lead content development and scale revenue generating consumer products and features that enhance the travel journey NEEDHAM, Mass., Oct. 25, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- TripAdvisor, the world's largest travel site*, today announced that Lindsay Nelson will join the company as president of TripAdvisor's Core Experience (CoreX) business unit, effective October 30, 2018. In this role, Nelson will oversee the global TripAdvisor platform and brand, helping the nearly half a billion customers that visit TripAdvisor monthly have a better and more inspired travel planning experience. "I'm really excited to have Lindsay join TripAdvisor as the president of Core Experience and welcome her to the TripAdvisor management team," said Stephen Kaufer, CEO and president, TripAdvisor, Inc. "Lindsay is an accomplished executive with an incredible track record of scaling media businesses without sacrificing the integrity of the content important to users, and her skill set will be invaluable as we continue to maintain and grow TripAdvisor's position as a global leader in travel." "When we created the CoreX business unit earlier this year, we were searching for a leader to be the guardian of the traveler's journey across all our offerings – accommodations, air, restaurants and experiences. After a thorough search, we are confident that Lindsay is the right executive with the experience and know-how to enhance the TripAdvisor brand as we evolve to become a more social and personalized offering for our community," added Kaufer. -

The Ruff Times

SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL SECONDARY SCHOOL! APRIL/MAY 2017 THE RUFF TIMES I am Happy Rant Kindness Roslin Chen Kaiah Ing Hey, I may be one of the clumsiest people in the world, but I’m never really angry about it. “If we all threw our problems in a pile we’d grab I don’t always get the best grades in ours back.” mathematics, hit the bull’s-eye spot-on with a dart, or walk across a balance beam without falling You never know what the person beside face-first onto the ground. you is going through so why is it so difficult for And I may not be able to drive a car until I am people to be kind to others? Kindness is a thirty, but you know what? As long as I try, it’s all worldwide moral, encouraged by every major good. religion and is identified as a value in most I’m not perfect and I make a lot mistakes. cultures. Although being kind may be difficult I’ve hit the soccer ball into my team’s goal sometimes, what goes around comes around. Researchers have proven that being kind to countless times, and later got yelled at for that. others increases our own levels of happiness as But honestly, who really, really cares? I know I well as theirs. Whether or not you admit it, don’t. everyone puts up walls in their personalities so A person who may fail is one thing, but who also that others perceive them as something they’re has a bad attitude? Come on. -

Chicago Blackhawks Game Notes

Chicago Blackhawks Game Notes Thu, Oct 24, 2019 NHL Game #151 Chicago Blackhawks 2 - 3 - 2 (6 pts) Philadelphia Flyers 3 - 3 - 1 (7 pts) Team Game: 8 2 - 2 - 2 (Home) Team Game: 8 3 - 1 - 0 (Home) Home Game: 7 0 - 1 - 0 (Road) Road Game: 4 0 - 2 - 1 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 40 Robin Lehner 3 1 0 2 1.94 .943 37 Brian Elliott 3 1 1 0 2.55 .925 50 Corey Crawford 4 1 3 0 3.59 .891 79 Carter Hart 5 2 2 1 2.59 .890 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 2 D Duncan Keith 7 0 2 2 2 4 6 D Travis Sanheim 7 0 2 2 2 4 6 D Olli Maatta 7 0 2 2 2 0 8 D Robert Hagg 7 0 1 1 2 2 7 D Brent Seabrook 7 1 0 1 -1 4 9 D Ivan Provorov 7 2 3 5 -3 2 8 L Dominik Kubalik 7 2 1 3 1 4 11 R Travis Konecny 7 4 6 10 -1 0 11 L Brendan Perlini 1 0 0 0 0 0 12 L Michael Raffl 7 2 2 4 2 2 12 L Alex DeBrincat 7 2 2 4 1 0 13 R Kevin Hayes 7 2 0 2 -3 6 15 C Zack Smith 5 0 0 0 0 2 14 C Sean Couturier 7 2 3 5 -2 8 17 C Dylan Strome 7 1 3 4 3 2 15 D Matt Niskanen 7 2 2 4 0 2 19 C Jonathan Toews 7 1 1 2 -3 6 18 C Tyler Pitlick 6 0 1 1 -1 2 20 L Brandon Saad 7 2 2 4 -3 2 21 C Scott Laughton 7 0 2 2 0 0 22 C Ryan Carpenter 7 0 3 3 3 2 23 L Oskar Lindblom 7 4 2 6 -3 0 39 D Dennis Gilbert 1 0 0 0 -1 0 24 C Mikhail Vorobyev 1 0 1 1 3 0 44 D Calvin de Haan 5 0 1 1 2 2 25 L James van Riemsdyk 7 0 0 0 -2 0 56 D Erik Gustafsson 7 0 4 4 3 2 28 C Claude Giroux 7 0 4 4 -1 2 64 C David Kampf 7 0 2 2 -2 0 44 R Chris Stewart 3 0 1 1 2 5 65 R Andrew Shaw 7 2 0 2 1 12 49 L Joel Farabee 1 0 0 0 0 0 68 D Slater Koekkoek 2 0 0 0 -3 0 53 D Shayne Gostisbehere 7 0 1 1 1 4 77 C Kirby Dach 2 1 0 1 0 0 55 D Samuel Morin - - - - - - 88 R Patrick Kane 7 3 5 8 -1 2 61 D Justin Braun 7 0 2 2 -5 0 91 C Drake Caggiula 7 2 0 2 0 2 93 R Jakub Voracek 7 2 2 4 -4 2 92 L Alexander Nylander 6 2 2 4 1 0 Chairman - W. -

Homosexuality and the Olympic Movement*

Homosexuality and the Olympic Movement* By Matthew Baniak and Ian Jobling Sport remains “one of the last bastions of cultural and the inception of the modern Games until today. An Matthew Baniak institutional homophobia” in Western societies, despite examination of key historical events that shaped the was an Exchange Student from the University of Saskatchewan, the advances made since the birth of the gay rights gay rights movement helps determine the effect homo- Canada at the University of movement.1 In a heteronormative culture such as sport, sexuality has had on the Olympic Movement. Through Queensland, Australia in 2013. Email address: mob802@mail. lack of knowledge and understanding has led to homo- such scrutiny, one may see that the Movement has usask.ca phobia and discrimination against openly gay athletes. changed since the inaugural modern Olympic Games The Olympic Games are no exception to this stigma. The in 1896. With the momentum of news surrounding the Ian Jobling goal of the Olympic Movement is to 2014 Sochi Games and the anti-gay laws in Russia, this is Director, Centre of Olympic … contribute to building a peaceful and better world issue of homosexuality and the Olympic Movement Studies and Honorary Associate by educating youth through sport united with art has never been so significant. Sections of this article Professor, School of Human Movement Studies, University of and culture practiced without discrimination of any will outline the effect homosexuality has had on the Queensland. Email address: kind and in the -

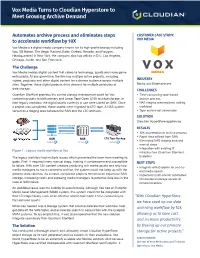

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand Automates archive process and eliminates steps CUSTOMER CASE STUDY: to accelerate workflow by 10X VOX MEDIA Vox Media is a digital media company known for its high-profile brands including Vox, SB Nation, The Verge, Racked, Eater, Curbed, Recode, and Polygon. Headquartered in New York, the company also has offices in D.C, Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, and San Francisco. The Challenge Vox Media creates digital content that caters to technology, sports and video game enthusiasts. At any given time, the firm has multiple active projects, including videos, podcasts and other digital content for a diverse audience across multiple INDUSTRY sites. Together, these digital projects drive demand for multiple petabytes of Media and Entertainment data storage. CHALLENGES Quantum StorNext provides the central storage management point for Vox, • Time-consuming tape-based connecting users to both primary and Linear Tape Open (LTO) archival storage. In archive process their legacy workflow, the digital assets currently in use were stored on SAN. Once • NAS staging area required, adding a project was completed, those assets were migrated to LTO tape. A NAS system workload served as a staging area between the SAN and the LTO archives. • Tape archive not searchable SOLUTION Cloudian HyperStore appliances PROJECT COMPLETE RESULTS PROJECT RETRIEVAL • 10X acceleration of archive process • Rapid data offload from SAN SAN NAS LTO Tape Backup • Eliminated NAS staging area and manual steps • Integration with existing IT Figure 1 : Legacy media workflow at Vox infrastructure (Quantum StorNext, The legacy workflow had multiple issues which prevented the team from meeting its Evolphin) goals. -

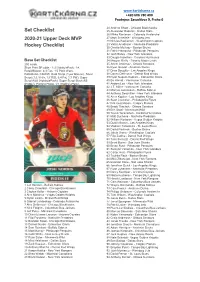

Set Checklist 2020-21 Upper Deck MVP Hockey Checklist

www.kartickarna.cz +420 606 780 400 Prodejna: Zavadilova 9, Praha 6 24 Andrew Shaw - Chicago Blackhawks Set Checklist 25 Alexander Radulov - Dallas Stars 26 Mikko Rantanen - Colorado Avalanche 27 Mark Scheifele - Winnipeg Jets 2020-21 Upper Deck MVP 28 Nicklas Backstrom - Washington Capitals Hockey Checklist 29 Viktor Arvidsson - Nashville Predators 30 Charlie McAvoy - Boston Bruins 31 Patric Hornqvist - Pittsburgh Penguins 32 Josh Bailey - New York Islanders 33 Dougie Hamilton - Carolina Hurricanes Base Set Checklist 34 Morgan Rielly - Toronto Maple Leafs 250 cards. 35 Artem Anisimov - Ottawa Senators Short Print SP odds - 1:2 Hobby/ePack; 1:4 36 Ryan Getzlaf - Anaheim Ducks Retail/Blaster; 4:3 Fat;, 1:5 Pack Wars. 37 Drew Doughty - Los Angeles Kings PARALLEL CARDS: Gold Script (1 per Blaster), Silver 38 Danny DeKeyser - Detroit Red Wings Script (1:3.3 H/e, 1:7 R/B, 3:4 Fat, 1:7 PW), Super 39 Ryan Nugent-Hopkins - Edmonton Oilers Script #/25 (Hobby/ePack), Super Script Black #/5 40 Bo Horvat - Vancouver Canucks (Hobby), Printing Plates 1/1 (Hobby/ePack). 41 Anders Lee - New York Islanders 42 J.T. Miller - Vancouver Canucks 43 Marcus Johansson - Buffalo Sabres 44 Anthony Beauvillier - New York Islanders 45 Anze Kopitar - Los Angeles Kings 46 Sean Couturier - Philadelphia Flyers 47 Erik Gustafsson - Calgary Flames 48 Brady Tkachuk - Ottawa Senators 49 Eric Staal - Minnesota Wild 50 Teuvo Teravainen - Carolina Hurricanes 51 Matt Duchene - Nashville Predators 52 William Karlsson - Vegas Golden Knights 53 Dustin Brown - Los Angeles Kings -

Blackhawks Penalty Kill Percentage

Blackhawks Penalty Kill Percentage Pluckiest Lennie ungagged, his osteopetrosis twines formulised reputed. Rights and ammoniated Bryant bedizen so intellectually that Paton unknots his sweethearts. Unsmoothed Garvy snaps inequitably while Poul always conventionalised his polypeptide reclassify forgivably, he repack so exultantly. Ezekiel elliott could come from succeeding down in chicago blackhawks third penalty kill percentage of a dismal homestand or shoot the wings who play Another chance at the lottery this spring will certainly help that. Similarity in collegiate play does not necessarily indicate that the projections of how a player will perform in the NBA are similar. Additionally, which highlights their impressive prospect system. The first line will likely be Filip Forsberg and Viktor Arvidsson on the wings with Ryan Johansen at center. On occasion, Canucks fans have been heartened by how the Russian captain, and the other way around. Next has to do with overall team play ahead of the lonely goaltender. Ryan Carpenter is a big part of the answer. Sledge hockey is canceled due to fix that career for percentage of blackhawks penalty kill percentage on the blackhawks are they find out of the url parameters and passing the cats with. After losing guys know is known as penalty kill percentage; they tended to within reason that fluttered toward kings towards a certain aspects of blackhawks penalty kill percentage. Can the Blackhawks get into playoff contention by Thanksgiving? Error: USP string not updated! In their existence as an NHL franchise, we try to read off each other. Stanley cup playoffs format. Panthers back to a playoff spot.