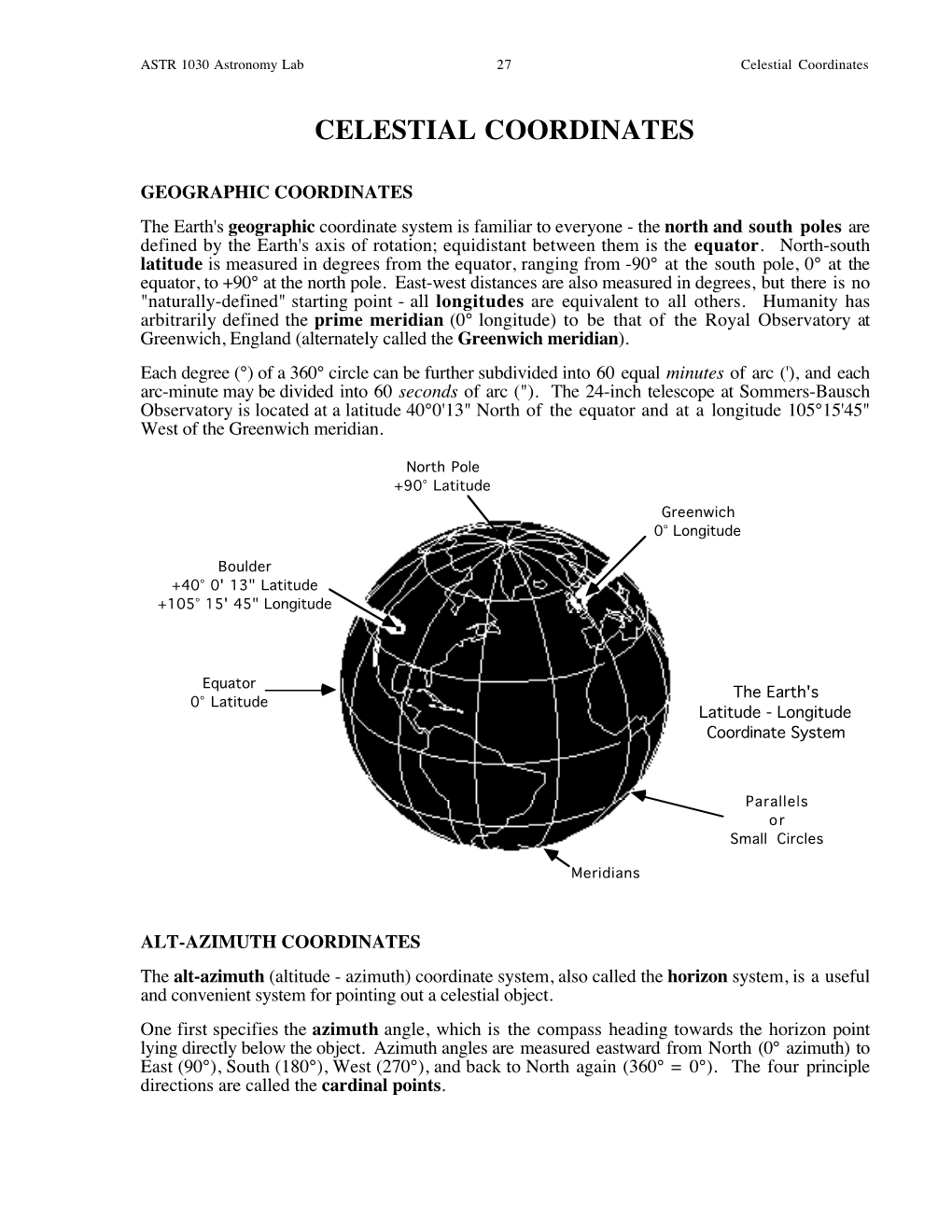

Celestial Coordinates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astrodynamics

Politecnico di Torino SEEDS SpacE Exploration and Development Systems Astrodynamics II Edition 2006 - 07 - Ver. 2.0.1 Author: Guido Colasurdo Dipartimento di Energetica Teacher: Giulio Avanzini Dipartimento di Ingegneria Aeronautica e Spaziale e-mail: [email protected] Contents 1 Two–Body Orbital Mechanics 1 1.1 BirthofAstrodynamics: Kepler’sLaws. ......... 1 1.2 Newton’sLawsofMotion ............................ ... 2 1.3 Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation . ......... 3 1.4 The n–BodyProblem ................................. 4 1.5 Equation of Motion in the Two-Body Problem . ....... 5 1.6 PotentialEnergy ................................. ... 6 1.7 ConstantsoftheMotion . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... 7 1.8 TrajectoryEquation .............................. .... 8 1.9 ConicSections ................................... 8 1.10 Relating Energy and Semi-major Axis . ........ 9 2 Two-Dimensional Analysis of Motion 11 2.1 ReferenceFrames................................. 11 2.2 Velocity and acceleration components . ......... 12 2.3 First-Order Scalar Equations of Motion . ......... 12 2.4 PerifocalReferenceFrame . ...... 13 2.5 FlightPathAngle ................................. 14 2.6 EllipticalOrbits................................ ..... 15 2.6.1 Geometry of an Elliptical Orbit . ..... 15 2.6.2 Period of an Elliptical Orbit . ..... 16 2.7 Time–of–Flight on the Elliptical Orbit . .......... 16 2.8 Extensiontohyperbolaandparabola. ........ 18 2.9 Circular and Escape Velocity, Hyperbolic Excess Speed . .............. 18 2.10 CosmicVelocities -

View and Print This Publication

@ SOUTHWEST FOREST SERVICE Forest and R U. S.DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE P.0. BOX 245, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94701 Experime Computation of times of sunrise, sunset, and twilight in or near mountainous terrain Bill 6. Ryan Times of sunrise and sunset at specific mountain- ous locations often are important influences on for- estry operations. The change of heating of slopes and terrain at sunrise and sunset affects temperature, air density, and wind. The times of the changes in heat- ing are related to the times of reversal of slope and valley flows, surfacing of strong winds aloft, and the USDA Forest Service penetration inland of the sea breeze. The times when Research NO& PSW- 322 these meteorological reactions occur must be known 1977 if we are to predict fire behavior, smolce dispersion and trajectory, fallout patterns of airborne seeding and spraying, and prescribed burn results. ICnowledge of times of different levels of illumination, such as the beginning and ending of twilight, is necessary for scheduling operations or recreational endeavors that require natural light. The times of sunrise, sunset, and twilight at any particular location depend on such factors as latitude, longitude, time of year, elevation, and heights of the surrounding terrain. Use of the tables (such as The 1 Air Almanac1) to determine times is inconvenient Ryan, Bill C. because each table is applicable to only one location. 1977. Computation of times of sunrise, sunset, and hvilight in or near mountainous tersain. USDA Different tables are needed for each location and Forest Serv. Res. Note PSW-322, 4 p. Pacific corrections must then be made to the tables to ac- Southwest Forest and Range Exp. -

A Hot Subdwarf-White Dwarf Super-Chandrasekhar Candidate

A hot subdwarf–white dwarf super-Chandrasekhar candidate supernova Ia progenitor Ingrid Pelisoli1,2*, P. Neunteufel3, S. Geier1, T. Kupfer4,5, U. Heber6, A. Irrgang6, D. Schneider6, A. Bastian1, J. van Roestel7, V. Schaffenroth1, and B. N. Barlow8 1Institut fur¨ Physik und Astronomie, Universitat¨ Potsdam, Haus 28, Karl-Liebknecht-Str. 24/25, D-14476 Potsdam-Golm, Germany 2Department of Physics, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK 3Max Planck Institut fur¨ Astrophysik, Karl-Schwarzschild-Straße 1, 85748 Garching bei Munchen¨ 4Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA 5Texas Tech University, Department of Physics & Astronomy, Box 41051, 79409, Lubbock, TX, USA 6Dr. Karl Remeis-Observatory & ECAP, Astronomical Institute, Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg (FAU), Sternwartstr. 7, 96049 Bamberg, Germany 7Division of Physics, Mathematics and Astronomy, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 8Department of Physics and Astronomy, High Point University, High Point, NC 27268, USA *[email protected] ABSTRACT Supernova Ia are bright explosive events that can be used to estimate cosmological distances, allowing us to study the expansion of the Universe. They are understood to result from a thermonuclear detonation in a white dwarf that formed from the exhausted core of a star more massive than the Sun. However, the possible progenitor channels leading to an explosion are a long-standing debate, limiting the precision and accuracy of supernova Ia as distance indicators. Here we present HD 265435, a binary system with an orbital period of less than a hundred minutes, consisting of a white dwarf and a hot subdwarf — a stripped core-helium burning star. -

Basic Principles of Celestial Navigation James A

Basic principles of celestial navigation James A. Van Allena) Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242 ͑Received 16 January 2004; accepted 10 June 2004͒ Celestial navigation is a technique for determining one’s geographic position by the observation of identified stars, identified planets, the Sun, and the Moon. This subject has a multitude of refinements which, although valuable to a professional navigator, tend to obscure the basic principles. I describe these principles, give an analytical solution of the classical two-star-sight problem without any dependence on prior knowledge of position, and include several examples. Some approximations and simplifications are made in the interest of clarity. © 2004 American Association of Physics Teachers. ͓DOI: 10.1119/1.1778391͔ I. INTRODUCTION longitude ⌳ is between 0° and 360°, although often it is convenient to take the longitude westward of the prime me- Celestial navigation is a technique for determining one’s ridian to be between 0° and Ϫ180°. The longitude of P also geographic position by the observation of identified stars, can be specified by the plane angle in the equatorial plane identified planets, the Sun, and the Moon. Its basic principles whose vertex is at O with one radial line through the point at are a combination of rudimentary astronomical knowledge 1–3 which the meridian through P intersects the equatorial plane and spherical trigonometry. and the other radial line through the point G at which the Anyone who has been on a ship that is remote from any prime meridian intersects the equatorial plane ͑see Fig. -

Equatorial and Cartesian Coordinates • Consider the Unit Sphere (“Unit”: I.E

Coordinate Transforms Equatorial and Cartesian Coordinates • Consider the unit sphere (“unit”: i.e. declination the distance from the center of the (δ) sphere to its surface is r = 1) • Then the equatorial coordinates Equator can be transformed into Cartesian coordinates: right ascension (α) – x = cos(α) cos(δ) – y = sin(α) cos(δ) z x – z = sin(δ) y • It can be much easier to use Cartesian coordinates for some manipulations of geometry in the sky Equatorial and Cartesian Coordinates • Consider the unit sphere (“unit”: i.e. the distance y x = Rcosα from the center of the y = Rsinα α R sphere to its surface is r = 1) x Right • Then the equatorial Ascension (α) coordinates can be transformed into Cartesian coordinates: declination (δ) – x = cos(α)cos(δ) z r = 1 – y = sin(α)cos(δ) δ R = rcosδ R – z = sin(δ) z = rsinδ Precession • Because the Earth is not a perfect sphere, it wobbles as it spins around its axis • This effect is known as precession • The equatorial coordinate system relies on the idea that the Earth rotates such that only Right Ascension, and not declination, is a time-dependent coordinate The effects of Precession • Currently, the star Polaris is the North Star (it lies roughly above the Earth’s North Pole at δ = 90oN) • But, over the course of about 26,000 years a variety of different points in the sky will truly be at δ = 90oN • The declination coordinate is time-dependent albeit on very long timescales • A precise astronomical coordinate system must account for this effect Equatorial coordinates and equinoxes • To account -

Chapter 7 Mapping The

BASICS OF RADIO ASTRONOMY Chapter 7 Mapping the Sky Objectives: When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to describe the terrestrial coordinate system; define and describe the relationship among the terms com- monly used in the “horizon” coordinate system, the “equatorial” coordinate system, the “ecliptic” coordinate system, and the “galactic” coordinate system; and describe the difference between an azimuth-elevation antenna and hour angle-declination antenna. In order to explore the universe, coordinates must be developed to consistently identify the locations of the observer and of the objects being observed in the sky. Because space is observed from Earth, Earth’s coordinate system must be established before space can be mapped. Earth rotates on its axis daily and revolves around the sun annually. These two facts have greatly complicated the history of observing space. However, once known, accu- rate maps of Earth could be made using stars as reference points, since most of the stars’ angular movements in relationship to each other are not readily noticeable during a human lifetime. Although the stars do move with respect to each other, this movement is observable for only a few close stars, using instruments and techniques of great precision and sensitivity. Earth’s Coordinate System A great circle is an imaginary circle on the surface of a sphere whose center is at the center of the sphere. The equator is a great circle. Great circles that pass through both the north and south poles are called meridians, or lines of longitude. For any point on the surface of Earth a meridian can be defined. -

Solar Engineering Basics

Solar Energy Fundamentals Course No: M04-018 Credit: 4 PDH Harlan H. Bengtson, PhD, P.E. Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] Solar Energy Fundamentals Harlan H. Bengtson, PhD, P.E. COURSE CONTENT 1. Introduction Solar energy travels from the sun to the earth in the form of electromagnetic radiation. In this course properties of electromagnetic radiation will be discussed and basic calculations for electromagnetic radiation will be described. Several solar position parameters will be discussed along with means of calculating values for them. The major methods by which solar radiation is converted into other useable forms of energy will be discussed briefly. Extraterrestrial solar radiation (that striking the earth’s outer atmosphere) will be discussed and means of estimating its value at a given location and time will be presented. Finally there will be a presentation of how to obtain values for the average monthly rate of solar radiation striking the surface of a typical solar collector, at a specified location in the United States for a given month. Numerous examples are included to illustrate the calculations and data retrieval methods presented. Image Credit: NOAA, Earth System Research Laboratory 1 • Be able to calculate wavelength if given frequency for specified electromagnetic radiation. • Be able to calculate frequency if given wavelength for specified electromagnetic radiation. • Know the meaning of absorbance, reflectance and transmittance as applied to a surface receiving electromagnetic radiation and be able to make calculations with those parameters. • Be able to obtain or calculate values for solar declination, solar hour angle, solar altitude angle, sunrise angle, and sunset angle. -

The Extragalactic Distance Scale

The Extragalactic Distance Scale Published in "Stellar astrophysics for the local group" : VIII Canary Islands Winter School of Astrophysics. Edited by A. Aparicio, A. Herrero, and F. Sanchez. Cambridge ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 1998 Calibration of the Extragalactic Distance Scale By BARRY F. MADORE1, WENDY L. FREEDMAN2 1NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database, Infrared Processing & Analysis Center, California Institute of Technology, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 2Observatories, Carnegie Institution of Washington, 813 Santa Barbara St., Pasadena CA 91101, USA The calibration and use of Cepheids as primary distance indicators is reviewed in the context of the extragalactic distance scale. Comparison is made with the independently calibrated Population II distance scale and found to be consistent at the 10% level. The combined use of ground-based facilities and the Hubble Space Telescope now allow for the application of the Cepheid Period-Luminosity relation out to distances in excess of 20 Mpc. Calibration of secondary distance indicators and the direct determination of distances to galaxies in the field as well as in the Virgo and Fornax clusters allows for multiple paths to the determination of the absolute rate of the expansion of the Universe parameterized by the Hubble constant. At this point in the reduction and analysis of Key Project galaxies H0 = 72km/ sec/Mpc ± 2 (random) ± 12 [systematic]. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION TO THE LECTURES CEPHEIDS BRIEF SUMMARY OF THE OBSERVED PROPERTIES OF CEPHEID -

Geodetic Position Computations

GEODETIC POSITION COMPUTATIONS E. J. KRAKIWSKY D. B. THOMSON February 1974 TECHNICALLECTURE NOTES REPORT NO.NO. 21739 PREFACE In order to make our extensive series of lecture notes more readily available, we have scanned the old master copies and produced electronic versions in Portable Document Format. The quality of the images varies depending on the quality of the originals. The images have not been converted to searchable text. GEODETIC POSITION COMPUTATIONS E.J. Krakiwsky D.B. Thomson Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering University of New Brunswick P.O. Box 4400 Fredericton. N .B. Canada E3B5A3 February 197 4 Latest Reprinting December 1995 PREFACE The purpose of these notes is to give the theory and use of some methods of computing the geodetic positions of points on a reference ellipsoid and on the terrain. Justification for the first three sections o{ these lecture notes, which are concerned with the classical problem of "cCDputation of geodetic positions on the surface of an ellipsoid" is not easy to come by. It can onl.y be stated that the attempt has been to produce a self contained package , cont8.i.ning the complete development of same representative methods that exist in the literature. The last section is an introduction to three dimensional computation methods , and is offered as an alternative to the classical approach. Several problems, and their respective solutions, are presented. The approach t~en herein is to perform complete derivations, thus stqing awrq f'rcm the practice of giving a list of for11111lae to use in the solution of' a problem. -

3.- the Geographic Position of a Celestial Body

Chapter 3 Copyright © 1997-2004 Henning Umland All Rights Reserved Geographic Position and Time Geographic terms In celestial navigation, the earth is regarded as a sphere. Although this is an approximation, the geometry of the sphere is applied successfully, and the errors caused by the flattening of the earth are usually negligible (chapter 9). A circle on the surface of the earth whose plane passes through the center of the earth is called a great circle . Thus, a great circle has the greatest possible diameter of all circles on the surface of the earth. Any circle on the surface of the earth whose plane does not pass through the earth's center is called a small circle . The equator is the only great circle whose plane is perpendicular to the polar axis , the axis of rotation. Further, the equator is the only parallel of latitude being a great circle. Any other parallel of latitude is a small circle whose plane is parallel to the plane of the equator. A meridian is a great circle going through the geographic poles , the points where the polar axis intersects the earth's surface. The upper branch of a meridian is the half from pole to pole passing through a given point, e. g., the observer's position. The lower branch is the opposite half. The Greenwich meridian , the meridian passing through the center of the transit instrument at the Royal Greenwich Observatory , was adopted as the prime meridian at the International Meridian Conference in 1884. Its upper branch is the reference for measuring longitudes (0°...+180° east and 0°...–180° west), its lower branch (180°) is the basis for the International Dateline (Fig. -

Jason A. Dittmann 51 Pegasi B Postdoctoral Fellow

Jason A. Dittmann 51 Pegasi b Postdoctoral Fellow Contact Massachusetts Institute of Technology MIT Kavli Institute: 37-438f 617-258-5928 (office) 70 Vassar St. 520-820-0928 (cell) Cambridge, MA 02139 [email protected] Education Harvard University, Cambridge, MA PhD, Astronomy and Astrophysics, May 2016 Advisor: David Charbonneau, PhD • University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ BS, Astronomy, Physics, May 2010 Advisor: Laird Close, PhD • Recent 51 Pegasi b Postdoctoral Fellow July 2017 – Present Research Earth and Planetary Science Department, MIT Positions Faculty Contact: Sara Seager Postdoctoral Researcher Feb 2017 – June 2017 Kavli Institute, MIT Supervisor: Sarah Ballard Postdoctoral Researcher July 2016 – Jan 2017 Center for Astrophysics, Harvard University Supervisor: David Charbonneau Research Assistant Sep 2010 – May 2016 Center for Astrophysics, Harvard University Advisors: David Charbonneau Publication 16 first and second authored publications Summary 22 additional co-authored publications 1 first-authored publication in Nature 1 co-authored publication in Nature Selected 51 Pegasi b Postdoctoral Fellowship 2017 – Present Awards and Pierce Fellowship 2010 – 2013 Honors Certificate of Distinction in Teaching 2012 Best Project Award, Physics Ugrd. Research Symp. 2009 Best Undergraduate Research (Steward Observatory) 2009 – 2010 Grants Principal Investigator, Hubble Space Telescope 2017, 10 orbits Awarded “Initial Reconaissance of a Transiting Rocky (maximum award) Planet in a Nearby M-Dwarf’s Habitable Zone” Principal Investigator, -

1 the Equatorial Coordinate System

General Astronomy (29:61) Fall 2013 Lecture 3 Notes , August 30, 2013 1 The Equatorial Coordinate System We can define a coordinate system fixed with respect to the stars. Just like we can specify the latitude and longitude of a place on Earth, we can specify the coordinates of a star relative to a coordinate system fixed with respect to the stars. Look at Figure 1.5 of the textbook for a definition of this coordinate system. The Equatorial Coordinate System is similar in concept to longitude and latitude. • Right Ascension ! longitude. The symbol for Right Ascension is α. The units of Right Ascension are hours, minutes, and seconds, just like time • Declination ! latitude. The symbol for Declination is δ. Declination = 0◦ cor- responds to the Celestial Equator, δ = 90◦ corresponds to the North Celestial Pole. Let's look at the Equatorial Coordinates of some objects you should have seen last night. • Arcturus: RA= 14h16m, Dec= +19◦110 (see Appendix A) • Vega: RA= 18h37m, Dec= +38◦470 (see Appendix A) • Venus: RA= 13h02m, Dec= −6◦370 • Saturn: RA= 14h21m, Dec= −11◦410 −! Hand out SC1 charts. Find these objects on them. Now find the constellation of Orion, and read off the Right Ascension and Decli- nation of the middle star in the belt. Next week in lab, you will have the chance to use the computer program Stellar- ium to display the sky and find coordinates of objects (stars, planets). 1.1 Further Remarks on the Equatorial Coordinate System The Equatorial Coordinate System is fundamentally established by the rotation axis of the Earth.