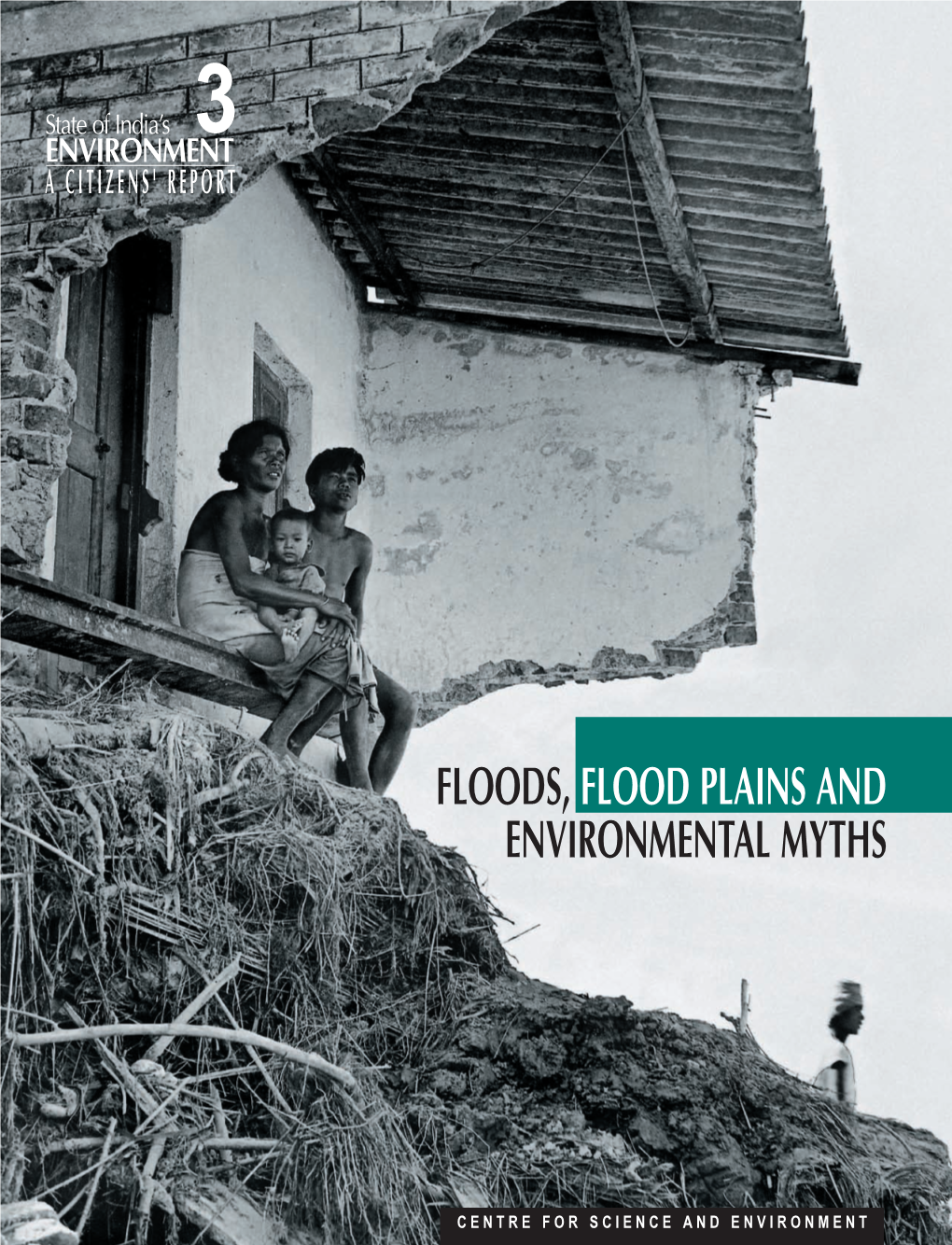

Floods, Flood Plains Andenvironmental Myths

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLACIERS of NEPAL—Glacier Distribution in the Nepal Himalaya with Comparisons to the Karakoram Range

Glaciers of Asia— GLACIERS OF NEPAL—Glacier Distribution in the Nepal Himalaya with Comparisons to the Karakoram Range By Keiji Higuchi, Okitsugu Watanabe, Hiroji Fushimi, Shuhei Takenaka, and Akio Nagoshi SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD Edited by RICHARD S. WILLIAMS, JR., and JANE G. FERRIGNO U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1386–F–6 CONTENTS Glaciers of Nepal — Glacier Distribution in the Nepal Himalaya with Comparisons to the Karakoram Range, by Keiji Higuchi, Okitsugu Watanabe, Hiroji Fushimi, Shuhei Takenaka, and Akio Nagoshi ----------------------------------------------------------293 Introduction -------------------------------------------------------------------------------293 Use of Landsat Images in Glacier Studies ----------------------------------293 Figure 1. Map showing location of the Nepal Himalaya and Karokoram Range in Southern Asia--------------------------------------------------------- 294 Figure 2. Map showing glacier distribution of the Nepal Himalaya and its surrounding regions --------------------------------------------------------- 295 Figure 3. Map showing glacier distribution of the Karakoram Range ------------- 296 A Brief History of Glacier Investigations -----------------------------------297 Procedures for Mapping Glacier Distribution from Landsat Images ---------298 Figure 4. Index map of the glaciers of Nepal showing coverage by Landsat 1, 2, and 3 MSS images ---------------------------------------------- 299 Figure 5. Index map of the glaciers of the Karakoram Range showing coverage -

The Alaknanda Basin (Uttarakhand Himalaya): a Study on Enhancing and Diversifying Livelihood Options in an Ecologically Fragile Mountain Terrain”

Enhancing and Diversifying Livelihood Options ICSSR PDF A Final Report On “The Alaknanda Basin (Uttarakhand Himalaya): A Study on Enhancing and Diversifying Livelihood Options in an Ecologically Fragile Mountain Terrain” Under the Scheme of General Fellowship Submitted to Indian Council of Social Science Research Aruna Asaf Ali Marg JNU Institutional Area New Delhi By Vishwambhar Prasad Sati, Ph. D. General Fellow, ICSSR, New Delhi Department of Geography HNB Garhwal University Srinagar Garhwal, Uttarakhand E-mail: [email protected] Vishwambhar Prasad Sati 1 Enhancing and Diversifying Livelihood Options ICSSR PDF ABBREVIATIONS • AEZ- Agri Export Zones • APEDA- Agriculture and Processed food products Development Authority • ARB- Alaknanda River Basin • BDF- Bhararisen Dairy Farm • CDPCUL- Chamoli District Dairy Production Cooperative Union Limited • FAO- Food and Agricultural Organization • FDA- Forest Development Agency • GBPIHED- Govind Ballabh Pant Institute of Himalayan Environment and Development • H and MP- Herbs and Medicinal Plants • HAPPRC- High Altitude Plant Physiology Center • HDR- Human Development Report • HDRI- Herbal Research and Development Institute • HMS- Himalayan Mountain System • ICAR- Indian Council of Agricultural Research • ICIMOD- International Center of Integrated Mountain and Development • ICSSR- Indian Council of Social Science Research LSI- Livelihood Sustainability Index • IDD- Iodine Deficiency Disorder • IMDP- Intensive Mini Dairy Project • JMS- Journal of Mountain Science • MPCA- Medicinal Plant -

“Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments and Coping Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin”

MS “Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments Thesis and Coping Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin” “ Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments and Coping and Induced Critical Moments Flood and of Drought Identification Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin River Lower Teesta Prone Hazard Strategies in This thesis paper is submitted to the department of Geography & Environmental Studies, University of Rajshahi, as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MS - 2015. SUBMITTED BY Roll No. 10116087 Registration No. 2850 Session: 2014 - 15 MS Exam: 2015 ” April, 2017 Department of Geography and Sk. Junnun Sk. Al Third Science Building Environmental Studies, Faculty of Life and Earth Science - Hussain Rajshahi University Rajshahi - 6205 April, 2017 “Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments and Coping Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin” This thesis paper is submitted to the department of Geography & Environmental Studies, University of Rajshahi, as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science - 2015. SUBMITTED BY Roll No. 10116087 Registration No. 2850 Session: 2014 - 15 MS Exam: 2015 April, 2017 Department of Geography and Third Science Building Environmental Studies, Faculty of Life and Earth Science Rajshahi University Rajshahi - 6205 Dedicated To My Family i Declaration The author does hereby declare that the research entitled “Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments and Coping Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin” submitted to the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Rajshahi for the Degree of Master of Science is exclusively his own, authentic and original study. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Acknowledgements xi Foreword xii I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY XIV II. INTRODUCTION 20 A. The Context of the SoE Process 20 B. Objectives of an SoE 21 C. The SoE for Uttaranchal 22 D. Developing the framework for the SoE reporting 22 Identification of priorities 24 Data collection Process 24 Organization of themes 25 III. FROM ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT TO SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT 34 A. Introduction 34 B. Driving forces and pressures 35 Liberalization 35 The 1962 War with China 39 Political and administrative convenience 40 C. Millennium Eco System Assessment 42 D. Overall Status 44 E. State 44 F. Environments of Concern 45 Land and the People 45 Forests and biodiversity 45 Agriculture 46 Water 46 Energy 46 Urbanization 46 Disasters 47 Industry 47 Transport 47 Tourism 47 G. Significant Environmental Issues 47 Nature Determined Environmental Fragility 48 Inappropriate Development Regimes 49 Lack of Mainstream Concern as Perceived by Communities 49 Uttaranchal SoE November 2004 Responses: Which Way Ahead? 50 H. State Environment Policy 51 Institutional arrangements 51 Issues in present arrangements 53 Clean Production & development 54 Decentralization 63 IV. LAND AND PEOPLE 65 A. Introduction 65 B. Geological Setting and Physiography 65 C. Drainage 69 D. Land Resources 72 E. Soils 73 F. Demographical details 74 Decadal Population growth 75 Sex Ratio 75 Population Density 76 Literacy 77 Remoteness and Isolation 77 G. Rural & Urban Population 77 H. Caste Stratification of Garhwalis and Kumaonis 78 Tribal communities 79 I. Localities in Uttaranchal 79 J. Livelihoods 82 K. Women of Uttaranchal 84 Increased workload on women – Case Study from Pindar Valley 84 L. -

Even the Himalayas Have Stopped Smiling

Even the Himalayas Have Stopped Smiling CLIMATE CHANGE, POVERTY AND ADAPTATION IN NEPAL 'Even the Himalayas Have Stopped Smiling' Climate Change, Poverty and Adaptation in Nepal Disclaimer All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holder requests that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the copyright holder, and a fee may be payable. This is an Oxfam International report. The affiliates who have contributed to it are Oxfam GB and Oxfam Hong Kong. First Published by Oxfam International in August 2009 © Oxfam International 2009 Oxfam International is a confederation of thirteen organizations working together in more than 100 countries to find lasting solutions to poverty and injustice: Oxfam America, Oxfam Australia, Oxfam-in-Belgium, Oxfam Canada, Oxfam France - Agir ici, Oxfam Germany, Oxfam GB, Oxfam Hong Kong, Intermon Oxfam, Oxfam Ireland, Oxfam New Zealand, Oxfam Novib and Oxfam Quebec. Copies of this report and more information are available at www.oxfam.org and at Country Programme Office, Nepal Jawalakhel-20, Lalitpur GPO Box 2500, Kathmandu Tel: +977-1-5530574/ 5542881 Fax: +977-1-5523197 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgements This report was a collaborative effort which draws on multiple sources, -

LIST of INDIAN CITIES on RIVERS (India)

List of important cities on river (India) The following is a list of the cities in India through which major rivers flow. S.No. City River State 1 Gangakhed Godavari Maharashtra 2 Agra Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 3 Ahmedabad Sabarmati Gujarat 4 At the confluence of Ganga, Yamuna and Allahabad Uttar Pradesh Saraswati 5 Ayodhya Sarayu Uttar Pradesh 6 Badrinath Alaknanda Uttarakhand 7 Banki Mahanadi Odisha 8 Cuttack Mahanadi Odisha 9 Baranagar Ganges West Bengal 10 Brahmapur Rushikulya Odisha 11 Chhatrapur Rushikulya Odisha 12 Bhagalpur Ganges Bihar 13 Kolkata Hooghly West Bengal 14 Cuttack Mahanadi Odisha 15 New Delhi Yamuna Delhi 16 Dibrugarh Brahmaputra Assam 17 Deesa Banas Gujarat 18 Ferozpur Sutlej Punjab 19 Guwahati Brahmaputra Assam 20 Haridwar Ganges Uttarakhand 21 Hyderabad Musi Telangana 22 Jabalpur Narmada Madhya Pradesh 23 Kanpur Ganges Uttar Pradesh 24 Kota Chambal Rajasthan 25 Jammu Tawi Jammu & Kashmir 26 Jaunpur Gomti Uttar Pradesh 27 Patna Ganges Bihar 28 Rajahmundry Godavari Andhra Pradesh 29 Srinagar Jhelum Jammu & Kashmir 30 Surat Tapi Gujarat 31 Varanasi Ganges Uttar Pradesh 32 Vijayawada Krishna Andhra Pradesh 33 Vadodara Vishwamitri Gujarat 1 Source – Wikipedia S.No. City River State 34 Mathura Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 35 Modasa Mazum Gujarat 36 Mirzapur Ganga Uttar Pradesh 37 Morbi Machchu Gujarat 38 Auraiya Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 39 Etawah Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 40 Bangalore Vrishabhavathi Karnataka 41 Farrukhabad Ganges Uttar Pradesh 42 Rangpo Teesta Sikkim 43 Rajkot Aji Gujarat 44 Gaya Falgu (Neeranjana) Bihar 45 Fatehgarh Ganges -

Floral and Faunal Diversity in Alaknanda River Mana to Devprayag

Report Code: 033_GBP_IIT_ENB_DAT_11_Ver 1_Jun 2012 Floral and Faunal Diversity in Alaknanda River Mana to Devprayag GRBMP : Ganga River Basin Management Plan by Indian Institutes of Technology IIT IIT IIT IIT IIT IIT IIT Bombay Delhi Guwahati Kanpur Kharagpur Madras Roorkee Report Code: 033_GBP_IIT_ENB_DAT_11_Ver 1_Jun 2012 2 | P a g e Report Code: 033_GBP_IIT_ENB_DAT_11_Ver 1_Jun 2012 Preface In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-sections (1) and (3) of Section 3 of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 (29 of 1986), the Central Government has constituted National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA) as a planning, financing, monitoring and coordinating authority for strengthening the collective efforts of the Central and State Government for effective abatement of pollution and conservation of the river Ganga. One of the important functions of the NGRBA is to prepare and implement a Ganga River Basin Management Plan (GRBMP). A Consortium of 7 Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) has been given the responsibility of preparing Ganga River Basin Management Plan (GRBMP) by the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF), GOI, New Delhi. Memorandum of Agreement (MoA) has been signed between 7 IITs (Bombay, Delhi, Guwahati, Kanpur, Kharagpur, Madras and Roorkee) and MoEF for this purpose on July 6, 2010. This report is one of the many reports prepared by IITs to describe the strategy, information, methodology, analysis and suggestions and recommendations in developing Ganga River Basin Management Plan (GRBMP). The overall Frame Work for documentation of GRBMP and Indexing of Reports is presented on the inside cover page. There are two aspects to the development of GRBMP. Dedicated people spent hours discussing concerns, issues and potential solutions to problems. -

Rivers of Peace: Restructuring India Bangladesh Relations

C-306 Montana, Lokhandwala Complex, Andheri West Mumbai 400053, India E-mail: [email protected] Project Leaders: Sundeep Waslekar, Ilmas Futehally Project Coordinator: Anumita Raj Research Team: Sahiba Trivedi, Aneesha Kumar, Diana Philip, Esha Singh Creative Head: Preeti Rathi Motwani All rights are reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission from the publisher. Copyright © Strategic Foresight Group 2013 ISBN 978-81-88262-19-9 Design and production by MadderRed Printed at Mail Order Solutions India Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India PREFACE At the superficial level, relations between India and Bangladesh seem to be sailing through troubled waters. The failure to sign the Teesta River Agreement is apparently the most visible example of the failure of reason in the relations between the two countries. What is apparent is often not real. Behind the cacophony of critics, the Governments of the two countries have been working diligently to establish sound foundation for constructive relationship between the two countries. There is a positive momentum. There are also difficulties, but they are surmountable. The reason why the Teesta River Agreement has not been signed is that seasonal variations reduce the flow of the river to less than 1 BCM per month during the lean season. This creates difficulties for the mainly agrarian and poor population of the northern districts of West Bengal province in India and the north-western districts of Bangladesh. There is temptation to argue for maximum allocation of the water flow to secure access to water in the lean season. -

Uttarakhand Flash Flood

Uttarakhand Flash Flood drishtiias.com/printpdf/uttarakhand-flash-flood Why in News Recently, a glacial break in the Tapovan-Reni area of Chamoli District of Uttarakhand led to massive Flash Flood in Dhauli Ganga and Alaknanda Rivers, damaging houses and the nearby Rishiganga power project. In June 2013, flash floods in Uttarakhand wiped out settlements and took lives. Key Points Cause of Flash Flood in Uttarakhand: It occurred in river Rishi Ganga due to the falling of a portion of Nanda Devi glacier in the river which exponentially increased the volume of water. Rishiganga meets Dhauli Ganga near Raini. So Dhauli Ganga also got flooded. Major Power Projects Affected: Rishi Ganga Power Project: It is a privately owned 130MW project. Tapovan Vishnugad Hydropower Project on the Dhauliganga: It was a 520 MW run-of-river hydroelectric project being constructed on Dhauliganga River. Several other projects on the Alaknanda and Bhagirathi river basins in northwestern Uttarakhand have also been impacted by the flood. 1/4 Flash Floods: About: These are sudden surges in water levels generally during or following an intense spell of rain. These are highly localised events of short duration with a very high peak and usually have less than six hours between the occurrence of the rainfall and peak flood. The flood situation worsens in the presence of choked drainage lines or encroachments obstructing the natural flow of water. Causes: It may be caused by heavy rain associated with a severe thunderstorm, hurricane, tropical storm, or meltwater from ice or snow flowing over ice sheets or snowfields. Flash Floods can also occur due to Dam or Levee Breaks, and/or Mudslides (Debris Flow). -

Microbiology ABSTRACT

Research Paper Volume : 4 | Issue : 11 | November 2015 • ISSN No 2277 - 8179 Microbiology Assessment of Physico-Chemical Parameters of KEYWORDS : Temperature, pH, Dissolved Oxygen, Biological Oxygen Demand River Ganga and Its Tributaries in Uttarakhand Department of Microbiology, Himalayan University, Naharlagun, Itanagar, Arunachal Nidhi Singh Chauhan Pradesh Manjul Dhiman Department of Botany, KLDAV PG College, Roorkee ABSTRACT Water quality assessment conducted in the tributaries of Ganga River in the year 2012 and 2013 identified hu- man activities as the main sources of pollution. For the study three tributaries of river Ganga in Uttarakhand were chosen i.e. Alaknanda (A), Bhagirathi (B) and Ganga (G). Water samples were collected from five sampling stations on river Alaknanda viz. Devprayag (A1), Rudraprayag (A2), Karnaprayag (A3), Chamoli (A4) and Vishnuprayag (A5), only one sampling station on Bhagirathi near residential area at Devprayag (B), two sampling station on river Ganga viz. Har ki pauri (G1) and Rishikesh (G2). The samples were analysed for physical and chemical parameters using standard methods. The sample temperatures ranged from 7.7 –18.3 0C. Summer maxima and winter minima were observed at all the sites of sampling stations (A, B and G). pH ranged from 7.4 - 8.2, DO ranged from 7 – 8.61 mg/l and BOD ranged from 0.2 – 1.9 mg/l. All samples showed permissible limit except samples from Harki pauri and Rishikesh on river Ganga. INTRODUCTION initiate biochemical reactions. These biochemical reactions are Rivers have been used by man since the dawn of civilization as measured as BOD and COD in laboratory (Tchobanoglous et al., a source of water, for food, for transport, as a defensive barrier, 2003). -

'Glacial Burst' in Uttarakhand

7 killed after ‘glacial burst’ in Uttarakhand Over 125 missing as hydel projects under construction on Rishiganga, Dhauliganga rivers are swept away SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT del project had an installed NEW DELHI capacity of 13.2 megawatts Seven persons were killed (MW), the 520 MW NTPC Ta- and over 125 reported mis- povan-Vishnugad project on sing after a “glacial burst” on the Dhauliganga was much Nanda Devi triggered an ava- larger. Both sites have been lanche and caused flash virtually washed away, an floods in Rishiganga and eyewitness told this new- Dhauliganga rivers in Cha- spaper. moli district of Uttarakhand Earlier in the day, Mr. Ra- on Sunday. wat said people along river- The number of missing banks were being evacuated. persons could rise as details Dams in Shrinagar and Rishi- were still being ascertained, kesh were emptied out, Mr. Uttarakhand Chief Minister Rawat said as the raging wa- T.S. Rawat said at a press ters made their way down- conference in Dehradun in stream. By late afternoon, the evening. Narrow escape: A worker being rescued from a tunnel at the the flow of the Alaknanda, of Videos of gushing waters Tapovan hydel project, which was washed away after the which the Dhauliganga is a and rising dust went viral on glacial burst in Uttarakhand on Sunday. * SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT tributary, had stabilised. social media as flood warn- Apart from the local pol- ings were issued in down- about the cause behind the povan tunnel of the NTPC ice and the Indo-Tibetan Bor- stream Uttar Pradesh for disaster,” the Chief Minister had to be halted due to a rise der Police (ITBP), four co- what was described as a “gla- told reporters. -

Use of Space Technology in Glacial Lake Outburst Flood Mitigation: a Case Study of Imja Glacier Lake

Use of Space Technology In Glacial Lake Outburst Flood Mitigation: A case study of Imja glacier lake Abstract: Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) triggered by the climate change affects the mountain ecosystem and livelihood of people in mountainous region. The use of space tools such as RADAR, GNSS, WiFi and GIS by the experts in collaboration with local community could contribute in achieving SDG-13 goals by assisting in GLOF risk identification and mitigation. Reducing geographical barriers, space technology can provide information about glacial lakes situated in inaccessible and high altitudes. A case study of application of these space tools in risk identification and mitigation of Imja Lake of Everest region is presented in this essay. Article: Introduction Climate change has emerged as one of the burning issues of the 21st century. According to Inter Governmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC), it is defined as ' a change of climate which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods' (IPCC, 2020). Some of its immediate impacts are increment of global temperature, extreme or low rainfall and accelerated melting of glaciers leading to Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF). The local people in the vicinity of potential hazards are the ones who have to suffer the most as a consequence of climate change. It would not only cause economic loss but also change the topography of the place, alter the social fabrics and create long-term livelihood issues which might take generations to recover.