School of Music Undergraduate Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

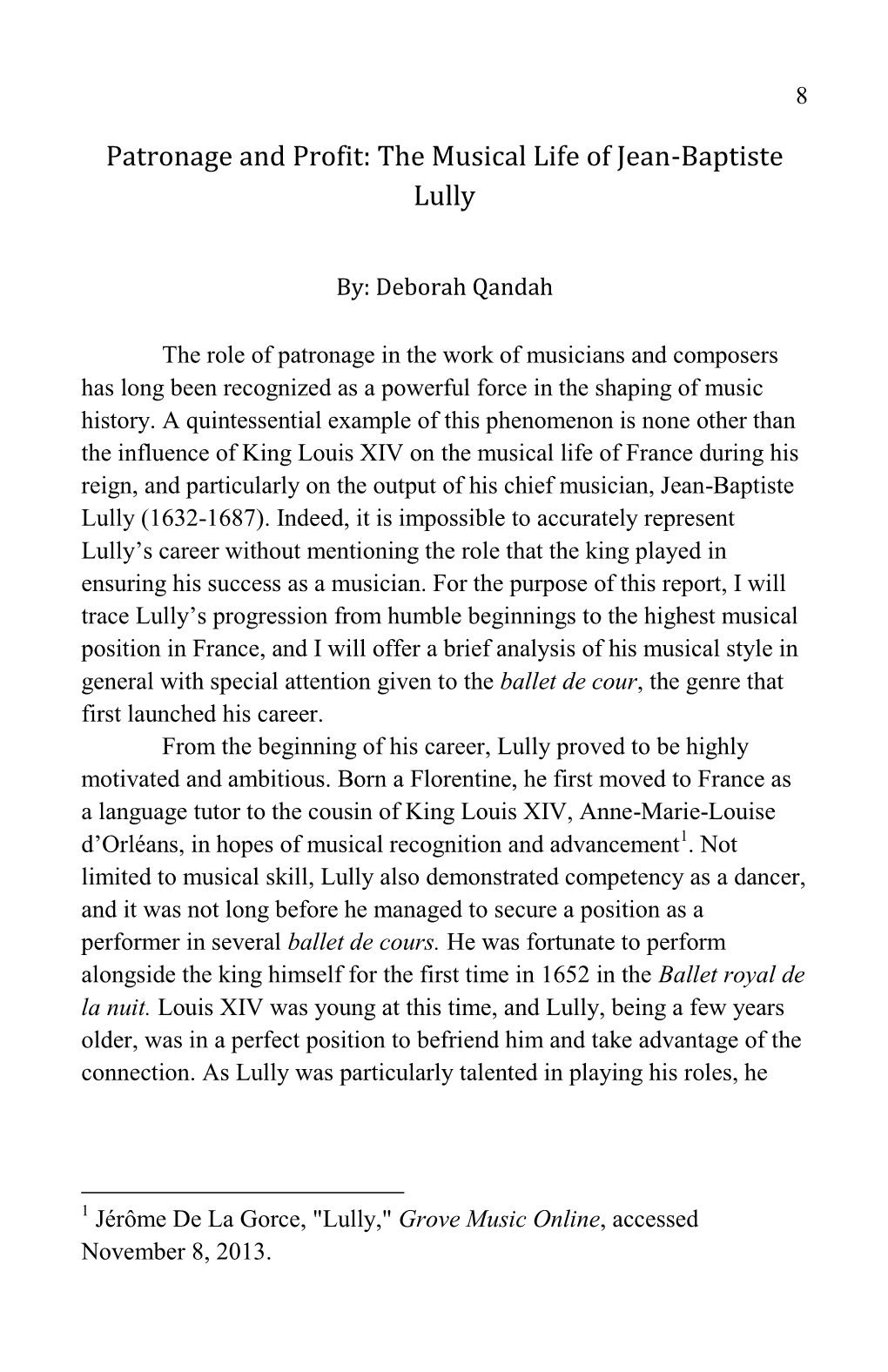

Recommended publications

-

Mini Page: Beautiful Ballet

© 2013 Universal Uclick Stay on Your Toes from The Mini Page © 2013 Universal Uclick Beautiful Ballet Think of all the different ways there are to tell a story. We can sing a song, The French King Louis XIV loved dance. In the mid-1600s, he started such as “Itsy Bitsy Spider.” An author a dance academy in Paris and often can relate a tale in a book. Actors can danced in its ballets. tell a story through a movie or play. This week, The Mini Page leaps into the world of ballet. When it first began, ballet, like many other types of dance, Ballerinas was another way to tell a story. In the 1700s and Ballet’s beginnings 1800s, ballerinas began to dance on pointe — The first ballet was believed to have up on their toes in taken place in 1581 — more than 400 special shoes called years ago! At that time, kings and pointe shoes. Famous queens kept huge courts of people ballerinas became known to serve and entertain them. Court for their special talents Pointe shoes entertainers wore fancy costumes and — jumps, turns or beautiful arms. performed speaking and singing roles, along with dancing and music. Europe and Russia The first ballet, the Ballet Comique Ballet became popular in Italy, de la Reine, was Royal influences France and Russia. In the early 20th performed in Ballet de cour, or court dance, called century, an arts promoter named Paris during for specific movements — pointed Sergei Diaghilev started a ballet a three-day feet and turned-out legs, for example. -

Eva Evdokimova (Western Germany), Atilio Labis

i THE CUBAN BALLET: ITS RATIONALE, AESTHETICS AND ARTISTIC IDENTITY AS FORMULATED BY ALICIA ALONSO A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Lester Tomé January, 2011 Examining Committee Members: Joellen Meglin, Advisory Chair, Dance Karen Bond, Dance Michael Klein, Music Theory Heather Levi, External Member, Anthropology ii © Copyright 2011 by Lester Tomé All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT In the 1940s, Alicia Alonso became the first Latin American dancer to achieve international prominence in the field of ballet, until then dominated by Europeans. Promoted by Alonso, ballet took firm roots in Cuba in the following decades, particularly after the Cuban Revolution (1959). This dissertation integrates the methods of historical research, postcolonial critique and discourse analysis to explore the performative and discursive strategies through which Alonso defined her artistic identity and the collective identity of the Cuban ballet. The present study also examines the historical context of the development of ballet in Cuba, Alonso’s rationale for the practice of ballet on the Island, and the relationship between the Cuban ballet and the European ballet. Alonso defended the legitimacy of Cuban dancers to practice ballet and, in specific, perform European classics such as Giselle and Swan Lake. She opposed the notion that ballet was the exclusive patrimony of Europeans. She also insisted that the cultivation of this dance form on the Island was not an act of cultural colonialism. In her view, the development of ballet in Cuba consisted, instead, of an exploration of a distinctive Cuban voice within this dance form, a reformulation of a European legacy from a postcolonial perspective. -

Dance Studies

CONVERSATIONS ACROSS THE FIELD OF DANCE STUDIES e Talking Point s . Society of Dance History Scholars Newsletter Illustrations: © Bibliothèque nationale Rethinking de France 19th Century Dance2011 | VolumeXXXI www.sdhs.org PAGE 1 A Word from the Guest Editors | Sarah Davies Cordova & Stephanie Schroedter ................. 3 Remembering The socio-political Fault-lines While Dancing at Quebec’s Winter Carnival | Charles R. Batson ............................................................... 4 Giselle at Mabille: Romantic Ballet and the Urban Dance Cultures of Paris | Stephanie Schroedter ........ 6 At Work on the Body: 1860s Parisian Tutus and Crinolines Or Women’s Silhouettes on Stage, at Fashionable Gatherings and in the Streets | Judith Chazin-Bennahum .................................................... 8 Why bother with Nineteenth-Century Ballet Libretti? | Debra H. Sowell ............................................ 12 CLOWNS , EL E PHANTS , AND BALL E RINAS . Joseph Cornell’s Vision of 19th Century Ballet in Dance Index (as collage) | Eike Wittrock ................. 14 From the Romantic to the Virtual | Norma Sue Fisher-Stitt ...................................................... 24 Notes & Pointεs from the field ................................ 26 Contributors .................................................................. 30 News SDHS Awards ............................................................................. 31 SDHS Publications. ..................................................................... 33 Forthcoming -

The Choreography of Space: Merce Cunningham and William Forsythe in Context

The Choreography of Space: Merce Cunningham and William Forsythe in Context Arabella Stanger Goldsmiths, University of London PhD April 2013 1 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own and has not been and will not be submitted, in whole or in part, to any other university for the award of any other degree. Arabella Stanger 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Maria Shevtsova for her rigorous supervision of this thesis. She has shown me the importance, and the enjoyment, of a way of thinking, and how ‘the art’ must lead in the scholarship of dance. Mentorship of this kind is invaluable. I would also like to thank my fellow postgraduate students at Goldsmiths, University of London for on-going conference around our shared and diverse subjects, and Dr Seb Franklin, for some inspiring conversations. I am extremely grateful to Freya Vass-Rhee of The Forsythe Company and David Vaughan of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company for giving me access to real treasures. The archives that have generously facilitated my research are: the Merce Cunningham Dance Company Archive, New York City; the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the New York Public Library; the Judson Memorial Church Collection, Fales Library, New York University; the Laban Archive, London; the National Resource Centre for Dance, University of Surrey, Guildford; and the Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin. My sincerest thanks go to the Arts and Humanities Research Council, for supporting this project and sponsoring a research trip to New York in 2009. This thesis is dedicated to the memory of Holly Webber. -

Career Timeline

PAMELA DELLAL CAREER TIMELINE Ensembles 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Handel & Haydn Society (1979-2003) Beethoven 9/Rink Terpsichore/Hogwood Messiah/Christie Lord Nelson/Labadie CPE Bach/Hogwood Messiah/Llewellen Boston Baroque (1983-2003) Sorceress *Lord Nelson B-minor Magic Flute Messiah St. Matthew Sposo Deluso Ulisse Emmanuel Music (1984-present) Bach Birthday Concert BWV 169 Brussels Magic Flute St. John BWV 170 St. Matthew Xmas O BWV 54 *St. John/*Xmas BWV 120 *BWV 20, 39, 76 BWV 169/St. John BWV 30 BWV 54/Jephtha BWV 169/Flute BWV 54/Alcina St John/B Minor St. Matthew BWV 35/Clemenza BWV 60 St Mark St. Matthew Xmas O Leipzig - cantatas Favella Lyrica (1990-2003) *Sweet Torment *Blind Love, Cruel Beauty Celebrity series BEMF Series *A New Sappho Ensemble Chaconne-Heart's Ease-El Dorado-Duo Mariesienne (1991-present) Heart's Ease; El Dorado; Duo Mariesienne chamber concerts Shakespeare tours (2001-2014) *Measure for Measure Ballet de Cour Tudor Music Masque of Beauty Sonate e Cantate A Masque of Characters Sequentia (1993-1999) *Canticles *Voice of Blood *O Jerusalem *Lux Refulget/*Shining*Saints *Ordo Virtutum and tour Cambridge Bach Ensemble (1994-2000) CBE *The Muses of Zion Stanford CA Prism Opera (1998-2010) Vanessa Lucretia Riders to the Sea Clemenza di Tito English arias Ch'io mi scordi di te Musicians of the Old Post Road (1998-2013) *Hummel Scottish -

Marie, Dancing Still - a New Musical a Closer Look

Marie, Dancing Still - A New Musical A Closer Look Marie’s World: A (Brief) History of Ballet allet is a formalized style of dance that originated in the Italian Renaissance BCourts of the 15th century. The word ballet comes from the Italian word ballare which means to dance. Elaborate celebrations for the noble men and women included dance and music that created a lavish spectacle for the guests. In 1533, when Catherine de Medici—an Italian noblewoman and a great patron of the arts—married French King Henry II, she introduced dance to the French court and began to support ballet in France. Her elaborate festivals included dance, costumes, music, song, and poetry. The costumes and headdresses were large and ornate which made it difficult for the dancers to move. Unlike the dramatic leaps and lifts we see in contemporary ballet, the dances of the ballet de cour (court ballet) were composed of small steps, hops, slides, and turns. The official language of ballet was codified in France over the next King Louis XIV as hundred years and is the reason that so many ballet terms are French words. the Sun King in the Ballet de la Nuit century later, French King Louis XIV, a passionate dancer himself, A popularized the dance form and even performed in many ballets, including the role of Sun King in the Ballet de la Nuit. In 1661, a dance academy was established in Paris and two decades later, ballet began to move from the courts to the stage. Ballet was incorporated into opera, creating a long-standing tradition of ballet-opera in France. -

Fêtes & Divertissements À La Cour

! FÊTES & DIVERTISSEMENTS À LA COUR 29 novembre 2016 - 26 mars 2017 DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE / FÊTES ET DIVERTISSEMENTS Établissement public du château, du musée et du domaine national DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE de Versailles – www.chateauversailles.fr Secteur éducatif - RP 834 - 78008 Versailles Cedex 01 30 83 78 00 – [email protected] !1 ! SOMMAIRE 3 PRÉFACE 5 PRÉSENTATION 6 AUTEURS 7 DIVERTISSEMENTS ÉQUESTRES 24 LIEUX ET DÉCORS DE L’ÉPHÉMÈRE 37 SPECTACLES DE SCÈNE 59 PROMENADES ET JEUX DE PLEIN AIR 68 DIVERTISSEMENTS D’APPARTEMENTS 96 LA FABRIQUE OU LES EFFETS DU MERVEILLEUX 112 RESSOURCES PÉDAGOGIQUES 116 BIBLIOGRAPHIE DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE / FÊTES ET DIVERTISSEMENTS Établissement public du château, du musée et du domaine national de Versailles – www.chateauversailles.fr Secteur éducatif - RP 834 - 78008 Versailles Cedex 01 30 83 78 00 – [email protected] !2 ! PRÉFACE Fêtes et divertissements à la Cour 29 novembre 2016 - 26 mars 2017 Salles d'Afrique et de Crimée En monarque politique, le roi Louis XIV a su porter au faîte de sa magnificence le « grand divertissement » faisant de Versailles un lieu de fêtes et de spectacles pour toujours plus de grandeur, d’extraordinaire et de fantastique. En fin psychologue, il a compris que « cette société de plaisirs, qui donne aux personnes de la cour une honnête familiarité avec [le souverain], les touche et les charme plus qu’on ne peut dire » (Louis XIV, Mémoires pour l’instruction du Dauphin, 1661) est nécessaire au cadre politique qu’il a instauré. Il faut, pour l’ordinaire de la vie de cour, de nombreux divertissements. Il faut, pour l’extraordinaire des événements royaux, étonner et émerveiller la cour, le royaume, l’Europe. -

Education Artistique Et Culturelle Histoire Des Arts, Itinéraire De La

Education artistique et culturelle Histoire des arts, itinéraire de la danse C Charvet-Néri janvier 2009 CPD EPS IA Rhône 1 Education artistique et culturelle, à travers des extraits d’œuvres chorégraphiques Le tour du monde en 8O danses C Picq Maison de la danse de Lyon En préambule : L’Education artistique et culturelle s’appuie sur le lien indissociable entre une pratique artistique et une éducation culturelle. C’est dans des aller- retours permanents entre une pratique artistique et des connaissances et rencontres culturelles (lieux, œuvres, artistes) que tous les élèves pourront se forger progressivement une identité à partir de laquelle il pourra s’inscrire dans la culture de leur temps. Ce document prend appui sur trois entrées pour aborder l’histoire de la danse, ceci permettra d’établir des liens entre les différentes disciplines, objectif de l’enseignement de l’histoire des arts à l’école. o chronologique, o thématique : les fêtes, les saisons, la ville o notionnel : les plans, les répétitions, les citations, la déformation Une société évolue dans ses pratiques corporelles comme dans ses normes culturelles, chaque peuple pour des motifs différents danse. Ainsi, la danse peut représenter un rituel, un divertissement, un art. Au fil du temps, ces différentes fonctions se sont progressivement différenciées, enrichies et construites, en trouvant un écho ou une utilité plus ou moins importante dans chaque société en lien étroit avec le contexte politique, social et culturel. Les fonctions de la danse et ses pratiques sont donc multiples et multiformes. Les danses rituelles, et traditionnelles ont traversé les âges, certaines danses se sont transformées en danse de divertissement, de bal et de salon, d’autres en danse de spectacle pour s’imposer comme discipline artistique. -

Learn About the Hit TV Show Dance Moms! $3.99

Learn about the hit TV show Dance Moms! How much does it cost to be a dancer? $3.99 Dear Reader, process, I got some writers who were willing I hope you have enjoyed the past issues of to write for me. This being a dance Dancer’s Corner as much as I have. I wrote magazine, finding writers was a difficult this magazine to show people what it takes task. Many people did not feel comfortable to be a dancer, and to have fun with dance. with writing about dance. Some writers When I initially started this thinking backed out when I needed them most, but process, I intended the magazine to be just others came through. I was becoming for dancers. Whether it was competition, stressed about putting the magazine recreational, or independent. It turned out together, but it worked in the end. to become a guide for dancers and for future I got to work with some amazing dancers. To help the parents as much as the writers while creating this magazine. These kids, and to support your passion. I look at writers were dedicated and even if they other dance magazines and they are all didn’t know all that much about dance, they focused on the big dancers. While they came through to write for me. An article write about others people’s that stood out to me was written by someone accomplishments, you are trying to achieve who does not dance, but was willing to help your own goals. That’s what sets Dancer’s me. -

THEA 166 Syllabus Final

Edward (Ted) Warburton Theater Arts Department University of California, Santa Cruz Ballet: 1156 High Street, Office A-218 Santa Cruz, CA 95064 A history Tel: 831.459.4542; E-mail: [email protected] Homepage: people.ucsc.edu/tedw Office Hours: TBA COURSE DESCRIPTION & REQUIREMENTS THEA 166, Ballet: A history presents a critical and historical overview of ballet as a form of ethnic dance. By ethnic dance, we mean to convey the idea that all forms of dance reflect the cultural traditions within which they developed. The course overview is both chronological and critical-artistic, fleshing out the technical, sociological, and aesthetic evolution of the form from the 16th century to present day. This course will chart a ballet diaspora as Russian émigrés moved through Europe to the Americas and Asia throughout the 20th Century. These influential choreographers, dancers, impresarios, and teachers brought with them the Imperial Russian ballet technique, classical dance repertoire, and a training system devised by the Russian dancer and pedagogue Agrippina Vagonova (1879—1951). Contrary to popular belief, however, ballet in the 20th century and the peoples who dance ballet did not develop into a monolithic whole. While the embodiment of ballet technique is instantly recognizable, ethnicity and race intersected with other socially and historically constructed categories—such as gender, class, and sexual orientation—to shape unique varieties of ballet habitus and identity formation in individuals and institutions in countries as geographically and ideologically diverse as China, Cuba, and the United States. This course aims to cultivate a culturally and historically informed understanding of the art form of ballet. -

Biomechanical Perspectives on Classical Ballet Technique and Implications for Teaching Practice

BIOMECHANICAL PERSPECTIVES ON CLASSICAL BALLET TECHNIQUE AND IMPLICATIONS FOR TEACHING PRACTICE Rachel Evelyn Ward A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Risk and Safety Sciences Faculty of Science University of New South Wales Sydney, Australia September 2012 P)..EASE TYPE THI; UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES l',toslsiOI!.isurtatlun Sheet SuuumtL! or Fanuly name Wa1d Otht;H name/3: ElJolyn Abbrevootion for de~ree a• _given In the UniVersity calendar PhD Sohoor. Stlloot ol Rls~ &nd Safety Sciences Faculty. FaO<Jity of Science TIUB! Biometllanfcal poll!pediVas On classical ballet techniqUe and Implications for teac~ tng practice Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Classical ballet ls an 1111 foun wen known I(U 115: vury dllittnct ilnd precise movement styla. A review of retsvant. lltetature led (o lt'le tde'nlifitatlOn oJ four fundamental blornechanlcal pn'nelple& of class.lcal ballet tedmlqll« '"al!gnm:en,•; •platement", 1utnoul"'-, .ond "extellstorf . The capacity to ex•cuta technique cor(ectJy 45 a rundame:nt~l pretequ!"ite for a SiJCGe$$ful career-as a professional clnSsical ballal aa"~'· Given thiS. 111e avenlgC<J )Ctncmauc aata flom pfofc:ss1r.ma1 Oal!et danccw; pttrtiJttrlmg core ballet -slepa provide-& a practfcsl blo,.,echanlcal ban~l't'lill'tl' of ' correct' lochnlquo_ Ti'oroo-dlmoMional (30) IUII-I)ody motion analysis Of 14 b3llet steps ms osoo to eompme the J>CffOI1ll3hC<! ul p1uftr.~sionat classiCal ball•l da"''""' (N•12} wltll that ol non-profess>anaf baUel dance IS (Na lA}, snd 10 invesVgato the '"""' of agreement between practical execut1on of the steps Willi ll'le lfleoretlcaf kfeals. -

RENAISSANCE COURT DANCE in ITALY and FRANCE a Short Summary Catherine

RENAISSANCE COURT DANCE in ITALY and FRANCE A Short Summary Catherine Sim RENAISSANCE COURT DANCE in ITALY and FRANCE A Short Summary Catherine Sim Catherine Sim Preface The major development of Renaissance dance took place in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. This development did not pro- ceed in a chronological through line; some elements and conditions were present in both centuries, and characteri◊ics of some dance forms overlapped. These pages contain a breakdown by century where possible. This book is meant to be a short summary of what is known so far of the why and wherefore of Renaissance dance in Italy and France. For those who wish to pursue this intriguing story, the references in the bibliography contain a wealth of useful and fascinating information. Catherine Sim RENAISSANCE COURT DANCE IN ITALY AND FRANCE Moreover, I was present in Venice when the Emperor [Frederick III] came, and the festivities that took place were the most noble that I ever saw in all my lifetime; …And the Signory arranged dancing one evening and I organized a most noble entertainment of a livery[set] of masques with new balli. And on that evening I was knighted. And in all Christendom there never took place a finer celebration or a finer repast.1 This entry from the Autobiography of Guglielmo Ebreo (William the Jew) of Pisaro is one of a long list of festivities in which he took part during the course of his thirty-year career as a dancing master in fifteenth-century Italy. Italy led the development of dance, both social and theatrical, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, with France destined to take the lead in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.