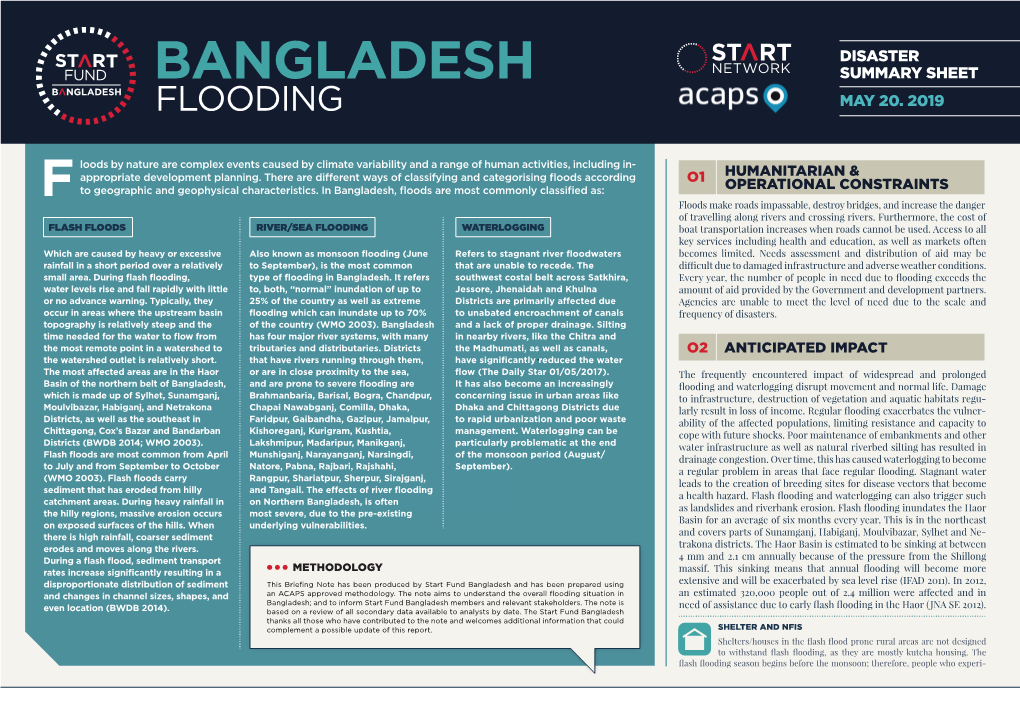

Bangladesh Summary Sheet B Ngladesh Flooding May 20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Hydrological Impacts of Climate Change on Rice

Hydrological impacts of climate change on rice cultivated riparian wetlands in the Upper Meghna River Basin (Bangladesh and India) Mohammed M. Rahman a,b,*, Julian R. Thompson b, and Roger J. Flower b a Department of Irrigation and Water Management, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh, Bangladesh b Wetland Research Unit, Department of Geography, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK * Corresponding author: email [email protected] Tel: +88 01717 825850; Fax: +88 091 61510 Abstract Riparian depressional wetlands (haors) in the Upper Meghna River Basin of Bangladesh are invaluable agricultural resources. They are completely flooded between June and November and planted with Boro rice when floodwater recedes in December. However, early harvest period (April/May) floods frequently damage ripening rice. A calibrated/validated Soil and Water Assessment Tool for riparian wetland (SWATrw) model is perturbed with bias free (using an improved quantile mapping approach) climate projections from 17 general circulation models (GCMs) for the period 2031–2050. Projected mean annual rainfall increases (200–500 mm per 7–10%). However, during the harvest period lower rainfall (21–75%) and higher evapotranspiration (1–8%) reduces river discharge (5–18%) and wetland inundation (inundation fraction declines of 0.005–0.14). Flooding risk for Boro rice consequently declines (rationalized flood risk reductions of 0.02–0.12). However, the loss of cultivable land (15.3%) to increases in permanent haor inundation represents a major threat to regional food security. Keywords haor wetlands; Boro rice; floods; Bangladesh; climate change; SWAT 1 Introduction The potential consequences of climate change on hydrological processes and associated sectors such as water resources, agriculture, aquatic ecology and human livelihoods have been extensively documented (e.g. -

Rhd Road Network, Rangpur Zone

RHD ROAD NETWORK, RANGPUR ZONE Banglabandha 5 N Tentulia Nijbari N 5 Z 5 0 6 Burimari 0 INDIA Patgram Panchagarh Z Mirgarh 5 9 0 Angorpota 3 1 0 0 5 Z Dhagram Bhaulaganj Chilahati Atwari Z 57 Z 06 5 0 Kolonihat Boda 2 1 Tunirhat Gomnati 3 0 Dhaldanga 7 Ruhea Z 5 N 6 5 Z 5 0 0 Dimla 0 0 2 3 7 9 2 5 6 Z 54 INDIA 5 Debiganj Z50 Sardarhat Z 9 5 0 5 5 Domar Hatibanda Bhurungamari Baliadangi Z N Kathuria Boragarihat Z5 Bahadur Dragha 002 2 Z5 0 7 0 03 5 Thakurgaon Z RLY 7 R 0 Station 58 2 7 7 Jaldhaka 2 5 Bus 6 Dharmagarh Stand Z 5 1 Z Z5 70 029 Z5 Nekmand Z Mogalhat 5 Kaliganj 6 Z5 Tengonmari 17 Nageshwari 2 7 56 4 7 Z 2 09 1 Raninagar Kadamtala 0 Z 0 0 57 5 9 0 Z 0 5 Phulbari Z 5 5 2 Z 5 5 Z Namorihat 0 Kalibari 2 Khansama 16 6 5 56 Z 2 Z Z Aditmari 01 Madarganj 50 Z5018 N509 Z59 4 Ranisonkail N5 08 Tebaria Nilphamari Kishoreganj 8 Z5 Kutubpur 00 008 Lalmonirhat Bhitarbond Z5 Z 2 Z5018 Z5018 Shaptibari 5 2 6 4 Darwani Z 2 6 0 1 0 5 Manthanahat 5 R Z5 Z 9 6 Z 0 00 Pirganj Bakultala 0 Barabari 5 2 5 5 5 1 0 Z Z Z Z5002 7 5 5 Z5002 Birganj 0 0 02 Gangachara N 5 0 5 Moshaldangi Z5020 06 6 06 0 5 0 N 5 Haragach Haripur Z 7 0 N5 Habumorh Bochaganj 0 5 4 Z 2 Z5 61 3 6 5 1 11 Z 5 Taraganj 2 6 Kurigram 0 N Hazirhat 5 Kaharol 5 Teesta 18 Z N5 Ranirbandar N5 Z Kaunia Bridge Rajarhat Z Saidpur Rangpur Shahebganj 5 Beldanga 0 Medical 0 5 Shapla 6 1 more 1 1 more 0 0 5 5 25 Ghagat Z 50 N517 Z Z Bridge Taxerhat N5 Mohiganj 1 2 Mordern 6 4 more 5 02 Z 8 5 Z Shampur 0 Modhupur Z 5 Parbatipur 50 N Sonapukur Badarganj 1 Chirirbandar Z5025 0 Ulipur Datbanga Govt Z5025 Pirgachha College R 5025 Simultala Laldangi 5 Z Kolahat Z 8 Kadamtali Biral Cantt. -

Bangladesh - Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on Friday 20 November 2015

Bangladesh - Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on Friday 20 November 2015 Treatment of Jamaat-e-Islami/Shibir(student wing) by state/authorities In June 2015 a report published by the United States Department of State commenting on events of 2014 states: “ICT prosecutions of accused 1971 war criminals continued. No verdicts were announced until November, when the ICT issued death sentences in separate cases against Motiur Rahman Nizami and Mir Quasem Ali. At the same time, the Supreme Court Appellate Division upheld one of two death sentences against Mohammad Kamaruzzaman. All three men were prominent Jamaat leaders, and Jamaat called nationwide strikes in protest” (United States Department of State (25 June 2015) 2014 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – Bangladesh). This report also states: “On August 10, Shafiqul Islam Masud, assistant secretary of the Jamaat-e-Islami Dhaka City Unit, was arrested, charged, and held in police custody with 154 others for arson attacks and vandalism in 2013. He was arrested and held four additional times in August and September 2014. According to a prominent human rights lawyer, Masud's whereabouts during his detentions were unknown, and lawyers were not allowed to speak with him. Defense lawyers were not allowed to speak before the court during his September 23 and 25 court appearances” (ibid). This document also points out that: “In some instances the government interfered with the right of opposition parties to organize public functions and restricted the broadcasting of opposition political events. Jamaat's appeal of a 2012 Supreme Court decision cancelling the party's registration continued” (ibid). -

An Investigation on Failure of Embankments in Bangladesh

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine International Conference on Case Histories in (2008) - Sixth International Conference on Case Geotechnical Engineering Histories in Geotechnical Engineering 14 Aug 2008, 4:30pm - 6:00pm An Investigation on Failure of Embankments in Bangladesh Zakaria Hossain Mie University, Tsu, Mie, Japan Zahurul Islam Stamford University Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh Toshinori Sakai Mie University, Tsu, Mie, Japan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icchge Part of the Geotechnical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Hossain, Zakaria; Islam, Zahurul; and Sakai, Toshinori, "An Investigation on Failure of Embankments in Bangladesh" (2008). International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering. 4. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icchge/6icchge/session02/4 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article - Conference proceedings is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN INVESTIGATION ON FAILURE OF EMBANKMENTS IN BANGLADESH Md. Zakaria Hossain Md. Zahurul Islam Toshinori Sakai Mie University Stamford University Bangladesh Mie University Tsu, Mie 514-8507, Japan Dhaka, Bangladesh Tsu, Mie 514-8507, Japan ABSTRACT The study presents the results of case histories on failure of embankments in Bangladesh based on the field visits to the embankments sites, collected data and information on failure of embankments necessary data related to embankments construction practice obtained from available publications and soil conditions of the breached embankments in Bangladesh. -

Moulvibazar Moulvibazar Is a District in the Division of Sylhet, Located in North-Eastern Bangladesh with an Area of 2,800 Square Kilometres

Moulvibazar Moulvibazar is a district in the division of Sylhet, located in north-eastern Bangladesh with an area of 2,800 square kilometres. It is surrounded by the Sylhet district in the north, Habiganj district in the west and Indian States of Assam and Tripura in the east and south respectively. The main BRAC rivers in the district are the Manu, the Dholoi and the Juri Photo credit: which flow from India. A community radio correspondent conducting an interview in Women Listeners Club. Although most of the population is Bengali, Moulvibazar has some indigenous inhabitants like Khashia, Monipuri and Tripura people. The poverty, BRAC works in the region Sylhet division is famous for its tea with a holistic approach. At a glance gardens, and Moulvibazar is no exception. Moulvibazar has around Moulvibazar has a naturally (as of December 2016) 92 gardens including rubber, green backdrop with scintillating bamboo and fruit gardens, like tea gardens. There are a lot of Microfinance pineapple, cane, jackfruit, oranges, places for tourists such as the agar, mango and lemon. The area Village organisations 1,833 Madhabkunda waterfall, Ham Members 154,868 is also home to the three largest Ham waterfall, Hakaluki haor, Borrowers 49,457 tea gardens (size and production Madhobpur Lake, Bilashchhara wise) in the world. The people Lake and last but not the least, the Progoti Small enterprise clients 5,331 of Moulvibazar mostly involved Lawachara National Park. in agriculture and gardening for their source of income. Most of Education BRAC’s core programmes, -

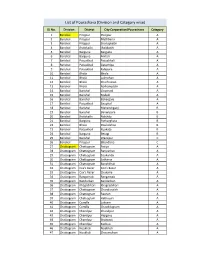

List of Pourashava (Division and Category Wise)

List of Pourashava (Division and Category wise) SL No. Division District City Corporation/Pourashava Category 1 Barishal Pirojpur Pirojpur A 2 Barishal Pirojpur Mathbaria A 3 Barishal Pirojpur Shorupkathi A 4 Barishal Jhalokathi Jhalakathi A 5 Barishal Barguna Barguna A 6 Barishal Barguna Amtali A 7 Barishal Patuakhali Patuakhali A 8 Barishal Patuakhali Galachipa A 9 Barishal Patuakhali Kalapara A 10 Barishal Bhola Bhola A 11 Barishal Bhola Lalmohan A 12 Barishal Bhola Charfession A 13 Barishal Bhola Borhanuddin A 14 Barishal Barishal Gournadi A 15 Barishal Barishal Muladi A 16 Barishal Barishal Bakerganj A 17 Barishal Patuakhali Bauphal A 18 Barishal Barishal Mehendiganj B 19 Barishal Barishal Banaripara B 20 Barishal Jhalokathi Nalchity B 21 Barishal Barguna Patharghata B 22 Barishal Bhola Doulatkhan B 23 Barishal Patuakhali Kuakata B 24 Barishal Barguna Betagi B 25 Barishal Barishal Wazirpur C 26 Barishal Pirojpur Bhandaria C 27 Chattogram Chattogram Patiya A 28 Chattogram Chattogram Bariyarhat A 29 Chattogram Chattogram Sitakunda A 30 Chattogram Chattogram Satkania A 31 Chattogram Chattogram Banshkhali A 32 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Cox’s Bazar A 33 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Chakaria A 34 Chattogram Rangamati Rangamati A 35 Chattogram Bandarban Bandarban A 36 Chattogram Khagrchhari Khagrachhari A 37 Chattogram Chattogram Chandanaish A 38 Chattogram Chattogram Raozan A 39 Chattogram Chattogram Hathazari A 40 Chattogram Cumilla Laksam A 41 Chattogram Cumilla Chauddagram A 42 Chattogram Chandpur Chandpur A 43 Chattogram Chandpur Hajiganj A -

127 Branches

মেটলাইফ পলললির প্রিপ্রিয়াি ও অꇍযাꇍয মপমেন্ট বযা廬ক এপ্রিয়ার িকল শাখায় ꇍগদে প্রদান কমর তাৎক্ষপ্রিকভাদব বমু ে লনন ররপ্রভপ্রꇍউ স্ট্যাম্প ও সীলসহ রিটলাইদের প্ররপ্রসট এই িলু বধা পাওয়ার জনয গ্রাহকমক মকান অলিলরক্ত লফ অথবা স্ট্যাম্প চাজ জ প্রদান করমি হমব না Sl. No. Division District Name of Branches Address of Branch 1 Barisal Barisal Barishal Branch Fakir Complex 112 Birshrashtra Captain Mohiuddin Jahangir Sarak 2 Barisal Bhola Bhola Branch Nabaroon Center(1st Floor), Sadar Road, Bhola 3 Chittagong Chittagong Agrabad Branch 69, Agrabad C/ A, Chittagong 4 Chittagong Chittagong Anderkilla Branch 184, J.M Sen Avenue Anderkilla 5 Chittagong Chittagong Bahadderhat Branch Mamtaz Tower 4540, Bahadderhat 6 Chittagong Chittagong Bank Asia Bhaban Branch 39 Agrabad C/A Manoda Mansion (2nd Floor), Holding No.319, Ward No.3, College 7 Chittagong Comilla Barura Branch Road, Barura Bazar, Upazilla: Barura, District: Comilla. 8 Chittagong Chittagong Bhatiary Branch Bhatiary, Shitakunda 9 Chittagong Brahmanbaria Brahmanbaria Branch "Muktijoddha Complex Bhaban" 1061, Sadar Hospital Road 10 Chittagong Chittagong C.D.A. Avenue Branch 665 CDA Avenue, East Nasirabad 1676/G/1 River City Market (1st Floor), Shah Amant Bridge 11 Chittagong Chaktai Chaktai Branch connecting road 12 Chittagong Chandpur Chandpur Branch Appollo Pal Bazar Shopping, Mizanur Rahman Road 13 Chittagong Lakshmipur Chandragonj Branch 39 Sharif Plaza, Maddho Bazar, Chandragonj, Lakshimpur 14 Chittagong Noakhali Chatkhil Branch Holding No. 3147 Khilpara Road Chatkhil Bazar Chatkhil 15 Chittagong Comilla Comilla Branch Chowdhury Plaza 2, House- 465/401, Race Course 16 Chittagong Comilla Companigonj Branch Hazi Shamsul Hoque Market, Companygonj, Muradnagar J.N. -

Factor Analysis of Water-Related Disasters in Bangladesh

ISSN 0386-5878 Technical Note of PWRI No.4068 Factor Analysis of Water-related Disasters in Bangladesh June 2007 The International Centre for Water Hazard and Risk Management PUBLIC WORKS RESEARCH INSTITUTE 1-6, Minamihara Tukuba-Shi, Ibaraki-Ken, 305-8516 Copyright ○C (2007) by P.W.R.I. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language without the written permission of the Chief Executive of P.W.R.I. この報告書は、独立行政法人土木研究所理事長の承認を得て刊行したものであ る。したがって、本報告書の全部又は一部の転載、複製は、独立行政法人土木研 究所理事長の文書による承認を得ずしてこれを行ってはならない。 Technical Note of PWRI No.4068 Factor Analysis of Water-related Disasters in Bangladesh by Junichi YOSHITANI Norimichi TAKEMOTO Tarek MERABTENE The International Centre for Water Hazard and Risk Managemant Synopsis: Vulnerability to disaster differs considerably depending on natural exposure to hazards and social conditions of countries affected. Therefore, it is important to take practical disaster mitigating measures which meet the local vulnerability conditions of the region. Designating Bangladesh as a research zone, this research aims to propose measures for strengthening the disaster mitigating system tailored to the region starting from identifying the characteristics of the disaster risk threatening the country. To this end, we identified the country’s natural and social characteristics first, and then analyzed the risk challenges and their background as the cause to create and expand the water-related disasters. Furthermore, we also analyzed the system -

SASEC Dhaka-Northwest Corridor Road Project Phase 2 Was Approved in October 2017

Semiannual Social Monitoring Report Loan No- 3592 Project No. 40540-017 December 2018 South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation Dhaka-Northwest Corridor Road Project, Phase 2 - Tranche 1 This Semiannual Social Monitoring Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Social Monitoring Report Third Semi-Annual Report BAN: SASEC Dhaka Northwest Corridor Road Project, Phase- 2 Improvement of Elenga-Hatikamrul-Rangpur Road to a 4 Lane Highway February 2019 Prepared by Ms. Hasina Khatun, Social Development Specialist, Project Implementation Consultant (PIC), SASEC RCP-II on behalf of the Roads and Highways Department (RHD), Ministry of Road Transport and Bridges for the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh and the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of 04 February’ 2019) Currency Unit – Bangladesh Taka (BDT) BDT 1.00 = $0.0119164 $1.00 BDT 83.9179 1 BDT = 0.0119164 USD1 USD = 83.9179 BDT. WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 1ha (Hectare) = 10000sq.m (square meter) Or 2.47 Acre Or 247 Decimal 1 Acre = 100 Decimal 1 km (kilometer) = 1000 m (Meter) 1 Metric Ton = 1000 kg (kilogram) ABBREVIATIONS AB - -

1 Small Area Estimation of Poverty in Rural

1 Bangladesh Journal of Agricultural Economics, XL 1&2 (2019): 1-16 SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF POVERTY IN RURAL BANGLADESH Md. Farouq Imam1 Mohammad Amirul Islam1 Md. Akhtarul Alam1* Md. Jamal Hossain1 Sumonkanti Das2 ABSTRACT Poverty is a complex phenomenon and most of the developing countries are struggling to overcome the problem. Small area estimation offers help to allocate resources efficiently to address poverty at lower administrative level. This study used data from Census 2011 and Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES)-2010. Using ELL and M-Quantile methods, this study identified Rangpur division as the poorest one where Kurigram is the poorest district. Finally, considering both upper and lower poverty lines this study identified the poverty estimates at upazila level of Rangpur division using ELL and M-Quantile methods. The analyses found that 32% of the households were absolute poor and 19% were extremely poor in rural Bangladesh. Among the upazilas under Rangpur division Rajarhat, Ulipur, Char Rajibpur, Phulbari, Chilmari, Kurigram Sadar, Nageshwari, and Fulchhari Upazilas have been identified as the poorest upazilas. Keywords: Small area, poverty, ELL, M-Quantile methods I. INTRODUCTION Bangladesh is a developing country in the south Asia. According to the recent statistics by Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS, 2017, HIES, 2010) the per capita annual income of Bangladesh is US$1610, estimated Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is 7.28, and the percentage below the poverty line (upper) is 24.30 percent. The population is predominantly rural, with about 70 percent people living in rural areas (HIES, 2016). In Bangladesh, poverty scenario was first surveyed in 1973-1974. -

Bangladesh – Impact of Anticipatory Action

Bangladesh Impact of Anticipatory Action Striking before the floods to protect agricultural livelihoods Efficient humanitarian assistance requires anticipation. For FAO, this means harnessing risk information systems to act faster and avert acute hunger. QU Dongyu FAO Director-General Bangladesh Impact of Anticipatory Action Striking before the floods to protect agricultural livelihoods Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Dhaka, 2021 REQUIRED CITATION FAO. 2021. Bangladesh – Impact of Anticipatory Action. Striking before the floods to protect agricultural livelihoods. Dhaka. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. ©FAO, 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. -

Bangladesh: a Sustainable and Disaster Resilient Future

Bangladesh: A Sustainable and Disaster Resilient Future 6th DIPECHO Action Plan Prepared by Syed Shahnawaz Ali Programme Manager-DRR Islamic Relief Worldwide-Bangladesh M. Mizanur Rahman Programme Officer (Monitoring, Evaluaon and Research) Islamic Relief Worldwide-Bangladesh Nushrat Rahman Chowdhury Assistant Project Officer Islamic Relief Worldwide-Bangladesh Edited by Syed Shahnawaz Ali Programme Manager-DRR Islamic Relief Worldwide-Bangladesh Published by Islamic Relief Worldwide-Bangladesh June 2012 Special thanks to Niger Dil Nahar, Md. Simon Rahman, Norul Alam Raju, Abdus Samad SKS Team Photo Dr. Marfy Ryhan Bradley Klees M. Mizanur Rahman Design and Producon Preview Dhaka, Bangladesh Contact Islamic Relief Worldwide - Bangladesh House No: 10, Road No: 10, Block-K, Baridhara, Dhaka-1212 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.irwbd.org This document has been prepared under the 6th DIPECHO Acon Plan for South Asia implemented by Islamic Relief Worldwide-Bangladesh working under the NARRI consorum. Islamic Relief Worldwide- Bangladesh preserves the copyright of this but it can be quoted or printed with proper acknowledgement. It has been produced with financial assistance from European Commission Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protecon (ECHO). The views expressed herein should not be taken, in any way, to reflect the official opinion of the European Commission Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protecon (ECHO). A Sustainable and Disaster Resilient Future Flood Prone Areas in Bangladesh A Sustainable and Disaster Resilient Future Introducon Bangladesh is one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world, suffering from regular floods, cyclones, earthquakes and drought. It is esmated that in the past 20 years, 135 million people in Bangladesh have been affected by natural disasters, and while many have lost their lives or been injured, millions of others have also lost their homes, land and livelihoods.