Title: Rice Consumption: Giffen Behavior in Rural Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangladesh - Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on Friday 20 November 2015

Bangladesh - Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on Friday 20 November 2015 Treatment of Jamaat-e-Islami/Shibir(student wing) by state/authorities In June 2015 a report published by the United States Department of State commenting on events of 2014 states: “ICT prosecutions of accused 1971 war criminals continued. No verdicts were announced until November, when the ICT issued death sentences in separate cases against Motiur Rahman Nizami and Mir Quasem Ali. At the same time, the Supreme Court Appellate Division upheld one of two death sentences against Mohammad Kamaruzzaman. All three men were prominent Jamaat leaders, and Jamaat called nationwide strikes in protest” (United States Department of State (25 June 2015) 2014 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – Bangladesh). This report also states: “On August 10, Shafiqul Islam Masud, assistant secretary of the Jamaat-e-Islami Dhaka City Unit, was arrested, charged, and held in police custody with 154 others for arson attacks and vandalism in 2013. He was arrested and held four additional times in August and September 2014. According to a prominent human rights lawyer, Masud's whereabouts during his detentions were unknown, and lawyers were not allowed to speak with him. Defense lawyers were not allowed to speak before the court during his September 23 and 25 court appearances” (ibid). This document also points out that: “In some instances the government interfered with the right of opposition parties to organize public functions and restricted the broadcasting of opposition political events. Jamaat's appeal of a 2012 Supreme Court decision cancelling the party's registration continued” (ibid). -

Preview Guide

ContentsNOT FOR SALE Preface xiii CHAPTER 3 The Behavior of Consumers 45 3.1 Tastes 45 CHAPTER 1 Indifference Curves 45 Supply, Demand, Marginal Values 48 and Equilibrium 1 More on Indifference Curves 53 1.1 Demand 1 3.2 The Budget Line and the Demand versus Quantity Consumer’s Choice 53 Demanded 1 The Budget Line 54 Demand Curves 2 The Consumer’s Choice 56 Changes in Demand 3 Market Demand 7 3.3 Applications of Indifference The Shape of the Demand Curve 7 Curves 59 The Wide Scope of Economics 10 Standards of Living 59 The Least Bad Tax 64 1.2 Supply 10 Summary 69 Supply versus Quantity Supplied 10 Author Commentary 69 1.3 Equilibrium 13 Review Questions 70 The Equilibrium Point 13 Numerical Exercises 70 Changes in the Equilibrium Point 15 Problem Set 71 Summary 23 Appendix to Chapter 3 77 Author Commentary 24 Cardinal Utility 77 Review Questions 25 The Consumer’s Optimum 79 Numerical Exercises 25 Problem Set 26 CHAPTER 4 Consumers in the Marketplace 81 CHAPTER 2 4.1 Changes in Income 81 Prices, Costs, and the Gains Changes in Income and Changes in the from Trade 31 Budget Line 81 Changes in Income and Changes in the 2.1 Prices 31 Optimum Point 82 Absolute versus Relative Prices 32 The Engel Curve 84 Some Applications 34 4.2 Changes in Price 85 2.2 Costs, Efficiency, and Gains from Changes in Price and Changes in the Trade 35 Budget Line 85 Costs and Efficiency 35 Changes in Price and Changes in the Optimum Point 86 Specialization and the Gains from Trade 37 The Demand Curve 88 Why People Trade 39 4.3 Income and Substitution Summary 41 -

Moulvibazar Moulvibazar Is a District in the Division of Sylhet, Located in North-Eastern Bangladesh with an Area of 2,800 Square Kilometres

Moulvibazar Moulvibazar is a district in the division of Sylhet, located in north-eastern Bangladesh with an area of 2,800 square kilometres. It is surrounded by the Sylhet district in the north, Habiganj district in the west and Indian States of Assam and Tripura in the east and south respectively. The main BRAC rivers in the district are the Manu, the Dholoi and the Juri Photo credit: which flow from India. A community radio correspondent conducting an interview in Women Listeners Club. Although most of the population is Bengali, Moulvibazar has some indigenous inhabitants like Khashia, Monipuri and Tripura people. The poverty, BRAC works in the region Sylhet division is famous for its tea with a holistic approach. At a glance gardens, and Moulvibazar is no exception. Moulvibazar has around Moulvibazar has a naturally (as of December 2016) 92 gardens including rubber, green backdrop with scintillating bamboo and fruit gardens, like tea gardens. There are a lot of Microfinance pineapple, cane, jackfruit, oranges, places for tourists such as the agar, mango and lemon. The area Village organisations 1,833 Madhabkunda waterfall, Ham Members 154,868 is also home to the three largest Ham waterfall, Hakaluki haor, Borrowers 49,457 tea gardens (size and production Madhobpur Lake, Bilashchhara wise) in the world. The people Lake and last but not the least, the Progoti Small enterprise clients 5,331 of Moulvibazar mostly involved Lawachara National Park. in agriculture and gardening for their source of income. Most of Education BRAC’s core programmes, -

Decisions and Games

DECISIONS AND GAMES. PART I 1. Preference and choice 2. Demand theory 3. Uncertainty 4. Intertemporal decision making 5. Behavioral decision theory DECISIONS AND GAMES. PART II 6. Static Games of complete information 7. Dynamic games of complete information 8. Static games of incomplete information 9. Dynamic games of incomplete information 10. Behavioral game theory References Gibbons, R. 1992. Game theory for applied economists. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. Varian, H.1992. Microeconomic analysis. Norton & Company. New York. Chapters 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 19. Camerer, C. , Loewenstein, G. , and Rabin, M. 2004. Advances in Behavioral Economics. Princeton University Press. Mas-Colell, A., Whinston, M., and Green, J. 1995. Microeconomic theory. Oxford University Press. Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, 6. 1 Two approaches to analyze behavior of decision makers. 1. From an abstract construction generate choices that satisfy rationality restrictions. 2. Directly from choice, ask for some structure to these choices and derive properties. Relation between the two approaches. 2 1. Preference and choice Consider a set of alternatives (mutually exclusives) X and we consider a preference relation on X. Preferences The preference relation “at least as good as” is a binary relation − over the set of alternatives X. Preferences express the ordering between alternatives resulting from the objectives of the decision maker. Properties: Rational Preference Relation (or Weak order, or Complete preorder) if -Completeness, Transitivity (and Reflexivity) A relation is complete if ∀∈x,,yXxy or yx. A relation is transitive if and only if ∀∈x,yz, X, if x≺≺y and y z, then x≺z. 3 Transitiveness is more delicate than completeness. -

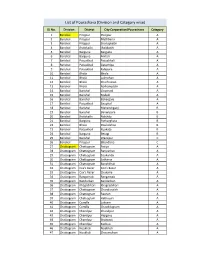

List of Pourashava (Division and Category Wise)

List of Pourashava (Division and Category wise) SL No. Division District City Corporation/Pourashava Category 1 Barishal Pirojpur Pirojpur A 2 Barishal Pirojpur Mathbaria A 3 Barishal Pirojpur Shorupkathi A 4 Barishal Jhalokathi Jhalakathi A 5 Barishal Barguna Barguna A 6 Barishal Barguna Amtali A 7 Barishal Patuakhali Patuakhali A 8 Barishal Patuakhali Galachipa A 9 Barishal Patuakhali Kalapara A 10 Barishal Bhola Bhola A 11 Barishal Bhola Lalmohan A 12 Barishal Bhola Charfession A 13 Barishal Bhola Borhanuddin A 14 Barishal Barishal Gournadi A 15 Barishal Barishal Muladi A 16 Barishal Barishal Bakerganj A 17 Barishal Patuakhali Bauphal A 18 Barishal Barishal Mehendiganj B 19 Barishal Barishal Banaripara B 20 Barishal Jhalokathi Nalchity B 21 Barishal Barguna Patharghata B 22 Barishal Bhola Doulatkhan B 23 Barishal Patuakhali Kuakata B 24 Barishal Barguna Betagi B 25 Barishal Barishal Wazirpur C 26 Barishal Pirojpur Bhandaria C 27 Chattogram Chattogram Patiya A 28 Chattogram Chattogram Bariyarhat A 29 Chattogram Chattogram Sitakunda A 30 Chattogram Chattogram Satkania A 31 Chattogram Chattogram Banshkhali A 32 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Cox’s Bazar A 33 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Chakaria A 34 Chattogram Rangamati Rangamati A 35 Chattogram Bandarban Bandarban A 36 Chattogram Khagrchhari Khagrachhari A 37 Chattogram Chattogram Chandanaish A 38 Chattogram Chattogram Raozan A 39 Chattogram Chattogram Hathazari A 40 Chattogram Cumilla Laksam A 41 Chattogram Cumilla Chauddagram A 42 Chattogram Chandpur Chandpur A 43 Chattogram Chandpur Hajiganj A -

127 Branches

মেটলাইফ পলললির প্রিপ্রিয়াি ও অꇍযাꇍয মপমেন্ট বযা廬ক এপ্রিয়ার িকল শাখায় ꇍগদে প্রদান কমর তাৎক্ষপ্রিকভাদব বমু ে লনন ররপ্রভপ্রꇍউ স্ট্যাম্প ও সীলসহ রিটলাইদের প্ররপ্রসট এই িলু বধা পাওয়ার জনয গ্রাহকমক মকান অলিলরক্ত লফ অথবা স্ট্যাম্প চাজ জ প্রদান করমি হমব না Sl. No. Division District Name of Branches Address of Branch 1 Barisal Barisal Barishal Branch Fakir Complex 112 Birshrashtra Captain Mohiuddin Jahangir Sarak 2 Barisal Bhola Bhola Branch Nabaroon Center(1st Floor), Sadar Road, Bhola 3 Chittagong Chittagong Agrabad Branch 69, Agrabad C/ A, Chittagong 4 Chittagong Chittagong Anderkilla Branch 184, J.M Sen Avenue Anderkilla 5 Chittagong Chittagong Bahadderhat Branch Mamtaz Tower 4540, Bahadderhat 6 Chittagong Chittagong Bank Asia Bhaban Branch 39 Agrabad C/A Manoda Mansion (2nd Floor), Holding No.319, Ward No.3, College 7 Chittagong Comilla Barura Branch Road, Barura Bazar, Upazilla: Barura, District: Comilla. 8 Chittagong Chittagong Bhatiary Branch Bhatiary, Shitakunda 9 Chittagong Brahmanbaria Brahmanbaria Branch "Muktijoddha Complex Bhaban" 1061, Sadar Hospital Road 10 Chittagong Chittagong C.D.A. Avenue Branch 665 CDA Avenue, East Nasirabad 1676/G/1 River City Market (1st Floor), Shah Amant Bridge 11 Chittagong Chaktai Chaktai Branch connecting road 12 Chittagong Chandpur Chandpur Branch Appollo Pal Bazar Shopping, Mizanur Rahman Road 13 Chittagong Lakshmipur Chandragonj Branch 39 Sharif Plaza, Maddho Bazar, Chandragonj, Lakshimpur 14 Chittagong Noakhali Chatkhil Branch Holding No. 3147 Khilpara Road Chatkhil Bazar Chatkhil 15 Chittagong Comilla Comilla Branch Chowdhury Plaza 2, House- 465/401, Race Course 16 Chittagong Comilla Companigonj Branch Hazi Shamsul Hoque Market, Companygonj, Muradnagar J.N. -

Giffen Behaviour and Asymmetric Substitutability*

Tjalling C. Koopmans Research Institute Tjalling C. Koopmans Research Institute Utrecht School of Economics Utrecht University Janskerkhof 12 3512 BL Utrecht The Netherlands telephone +31 30 253 9800 fax +31 30 253 7373 website www.koopmansinstitute.uu.nl The Tjalling C. Koopmans Institute is the research institute and research school of Utrecht School of Economics. It was founded in 2003, and named after Professor Tjalling C. Koopmans, Dutch-born Nobel Prize laureate in economics of 1975. In the discussion papers series the Koopmans Institute publishes results of ongoing research for early dissemination of research results, and to enhance discussion with colleagues. Please send any comments and suggestions on the Koopmans institute, or this series to [email protected] ontwerp voorblad: WRIK Utrecht How to reach the authors Please direct all correspondence to the first author. Kris De Jaegher Utrecht University Utrecht School of Economics Janskerkhof 12 3512 BL Utrecht The Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected] This paper can be downloaded at: http:// www.uu.nl/rebo/economie/discussionpapers Utrecht School of Economics Tjalling C. Koopmans Research Institute Discussion Paper Series 10-16 Giffen Behaviour and Asymmetric * Substitutability Kris De Jaeghera aUtrecht School of Economics Utrecht University September 2010 Abstract Let a consumer consume two goods, and let good 1 be a Giffen good. Then a well- known necessary condition for such behaviour is that good 1 is an inferior good. This paper shows that an additional necessary for such behaviour is that good 1 is a gross substitute for good 2, and that good 2 is a gross complement to good 1 (strong asymmetric gross substitutability). -

Illustrating the Difference Between Emissions Fees and Abatement Subsidies Using Isoquant and Isocost Geometry

Illustrating the Difference between Emissions Fees and Abatement Subsidies Using Isoquant and Isocost Geometry Emissions fees (taxes) and abatement subsidies are common policy solutions when negative externalities, such as pollution generated from production, impact market transactions. Textbook treatment of these two policies vary in exposition and detail and are generally more descriptive than analytical. This can leave students with limited insights regarding behavioral differences that arise with these policies. In illustrating unintended policy consequences, this graphical analysis illustrates that a subsidy policy is, paradoxically, more likely to generate more pollution than a fee policy, a result consistent with Metcalf’s (2009) empirical work and a result often not well articulated in textbooks. Christopher S Decker† †University of Nebraska at Omaha © 2020 Journal of Economics Teaching. All rights reserved. Decker / Journal of Economics Teaching (2020) 1. Introduction Since its inception, researchers in the field of environmental economics have developed a menu of policies for addressing the negative externality resulting when pollution results from production. Emissions fees (taxes) and abatement subsidies are some of the most common policy solutions discussed in most environmental economics courses. Textbook treatment of these two policies, however, vary in exposition and detail (e.g. Callan and Thomas, 2010; Field and Field, 2009; Kalstad, 2011; Perman, Ma, McGilvray, and Common, 2011; Tietenberg, 2003). However, it is fair to say that this approach, at least at the undergraduate level, is descriptive.1 Textbooks tend to offer examples of each policy as well as an overview of those states or countries that have implemented each. They correctly point out that emission fees tend to be more common in Europe than the United States. -

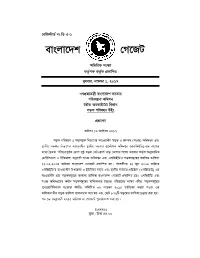

Evsjv‡`K †M‡RU

†iwR÷vW© bs wW G-1 evsjv‡`k †M‡RU AwZwi³ msL¨v KZ…©c¶ KZ…©K cÖKvwkZ eyaevi, b‡f¤^i 1, 2017 MYcÖRvZš¿x evsjv‡`k miKvi cwiKíbv Kwgkb ‡fŠZ AeKvVv‡gv wefvM moK cwienb DBs cÖÁvcb ZvwiLt 19 A‡±vei 2017 moK cwienb I gnvmoK wefv‡Mi AvIZvaxb moK I Rbc_ (mIR) Awa`ßi Ges ¯’vbxq miKvi wefv‡Mi AvIZvaxb ¯’vbxq miKvi cÖ‡KŠkj Awa`ßi (GjwRBwW)-Gi Kv‡Ri g‡a¨ ˆØZZv cwinvic~e©K †`‡k myôz moK †bUIqvK© M‡o †Zvjvi j‡ÿ¨ miKvi KZ©„K Aby‡gvw`Z †kÖYxweb¨vm I bxwZgvjv Abyhvqx mIR Awa`ßi Ges GjwRBwWÕi moKmg~‡ni mgwšZ^ ZvwjKv 11-02-2004 Zvwi‡L evsjv‡`k †M‡R‡U cÖKvwkZ nq| cieZ©x‡Z 12 Rby 2006 Zvwi‡L GjwRBwWÕi AvIZvaxb Dc‡Rjv I BDwbqb moK Ges ¯’vbxq miKvi cÖwZôvb (GjwRAvB) Gi AvIZvaxb MÖvg moKmg~‡ni Avjv`v ZvwjKv evsjv‡`k †M‡R‡U cÖKvwkZ nq| GjwRBwW Ges mIR Awa`߇ii Aaxb moKmg~‡ni gvwjKvbvi ˆØZZv cwinv‡ii j‡ÿ¨ MwVZ ÕmoKmg~‡ni cybt‡kYÖ xweb¨vm msµvšÍ ÷vwÛs KwgwUÕi 02 b‡f¤^i 2014 Zvwi‡Li mfvq mIR Gi gvwjKvbvaxb moK ZvwjKv nvjbvMv` Kiv nq Ges †gvU 876wU mo‡Ki ZvwjKv P‚ovšÍ Kiv nq| MZ 18 †deªæqvix 2015 Zvwi‡L Zv †M‡R‡U cybtcÖKvk Kiv nq| (14445) g~j¨ : UvKv 44.00 14446 evsjv‡`k †M‡RU, AwZwi³, b‡f¤^i 1, 2017 ÕmoKmg~‡ni cybt‡kªYxweb¨vm msµvš Í ÷vwÛs KwgwUÕi 02 b‡f¤^i 2014 Zvwi‡Li mfvq wm×vš Í M„nxZ nq †h ÕmIR Gi gvwjKvbvaxb mo‡Ki †M‡RU cÖKvwkZ nIqvi ci GjwRBwWÕi moKmg~‡ni ZvwjKv nvjbvMv` K‡i Zv †M‡RU AvKv‡i cÖKvk Ki‡Z n‡eÕ| G †cÖwÿ‡Z 11 †m‡Þ¤^i 2017 Zvwi‡L AbywôZ AvšÍtgš¿Yvjq KwgwUi mfvq GjwRBwW I GjwRAvB Gi nvjbvMv`K…Z ZvwjKv cybtch©v‡jvPbvc~e©K P‚ovš Í Kiv nq (cwiwkó-K) hv, gvbbxq cwiKíbv gš¿x KZ©„K Aby‡gvw`Z| G ZvwjKvq 4,781 wU Dc‡Rjv moK (ˆ`N©¨ 37,519.49 wK:wg:), 8,023 wU -

The Giffen Paradox Revisited

The Giffen Paradox Revisited Trieu Nguyen Economics Student, Hillsdale College Hillsdale, MI 49242, USA [email protected] ORCID ID: 0000-0002-8579-4879 Abstract This paper aims at defending Austrian causal-realist demand theory which refutes the existence of upward-sloping demand curve or the Giffen good. The analysis traces back to the fundamental difference between Austrian and neo-classical microeconomics, especially in utility theory. Additionally, this paper also briefly examines and proposes a rejoinder to the criticism of Hudik (2011a). Keywords: price theory, utility theory, demand theory, Giffen goods. JEL Classification: B53, D01 Acknowledgement: The idea of this paper emerged from a short conversation between the present author and Dr. Joseph Salerno at Mises University 2019 in which the present author was an attendee. He indebts the Economics Department of Hillsdale College including Dr. Michael Clark and Dr. Charles Steele, as well as Dr. Marek Hudik from University of Economics in Prague and Ohad Osterreicher of University of Bayreuth, Germany for their critical comments and constructive suggestion on earlier drafts of this paper. The standard disclaimer applies. 1. Introduction The comparison between neo-classical and Austrian economics has been a great constructive discussion in the economics profession. Unfortunately, for the most part, the scope of the discussion is indeed macroscopic and from a methodological ground. As Klein (2008) pointed out, what make the Austrian school distinct from the neo-classical framework, i. e. the heart of the Austrian analysis, are “price theory, capital theory, monetary theory, business-cycle theory, and the theory of interventionism.” Among these topics, though there exists similarity, the dehomogenization between Austrian and neo-classical price theory deserves much more attention than what it is having now within the profession. -

Field Experiments: Design and Policy

Field Experiments: Design and Policy Lecture 1 HSE, 6.10.2014 Dagmara Celik Katreniak Course Overview • Part I: Field Experiments – Introduction to Randomized Control Trials (RCTs) • Why to randomize? • Field versus Lab Experiments – Experimental Design • Types of designs, designing stages • Implementation of an RCT • Implementation issues (attrition, spillover, selection, …) – Data Analysis • Treatment effects Course Overview • Part II: Topics in Development Economics – Field experiments in health – Field experiments in education – Field experiments in consumer choice – Field experiments in labor economics – Field experiments in microfinance – Field experiments in credit and savings Outcome • Proposal – Topic closest to your interest – Literature review – Arguments for the proposed project – Methodology – Sample size and power calculation – Budget – Logistics and Implementation, suggested solutions for possible implementation issues Expectations and Evaluation • Attendance (5% of final score) • Reading list • Quizzes (15% of final score) • Midterm examination (20% of final score) • Final examination (30% of final score) • Proposal presentation (first draft) – Individual or in pairs • Proposal (final draft, 30% of final score) Contact • Office hours: on request • Email: [email protected] • Course website: hopefully soon Today • Experimental Economics • Types of Experiments – Laboratory Experiments – Natural Experiments – Field Experiments – Laboratory Experiments in the Field • Program Evaluations • Randomized Control Trials • Randomization -

Economics for Investment Decision Makers Workbook

ECONOMICS FOR INVESTMENT DECISION MAKERS WORKBOOK CFA Institute is the premier association for investment professionals around the world, with over 117,000 members in 134 countries. Since 1963 the organization has developed and administered s the renowned Chartered Financial Analyst Program. With a rich history of leading the investment profession, CFA Institute has set the highest standards in ethics, education, and professional excellence within the global investment community, and is the foremost authority on investment profession conduct and practice. Each book in the CFA Institute Investment Series is geared toward industry practitioners along with graduate-level finance students and covers the most important topics in the industry. The authors of these cutting-edge books are themselves industry professionals and academics and bring their wealth of knowledge and expertise to this series. ECONOMICS FOR INVESTMENT DECISION MAKERS WORKBOOK Micro, Macro, and International Economics Christopher D. Piros, CFA Jerald E. Pinto, CFA Cover Design: Leiva-Sposato Cover Image: ª Maciej Noskowski / iStockphoto Copyright ª 2013 by CFA Institute. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright .com.