Surviving a Tiger Attack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report ______January 01 –December 31, 2003

Phoenix Final Report ____________________________________________________________________________________ January 01 –December 31, 2003 FINAL REPORT January 01 – December 31, 2003 The Grantor: Save the Tiger Fund Project No: № 2002 – 0301 – 034 Project Name: “Operation Amba Siberian Tiger Protection – III” The Grantee: The Phoenix Fund Report Period: January 01 – December 31, 2003 Project Period: January 01 – December 31, 2003 The objective of this project is to conserve endangered wildlife in the Russian Far East and ensure long-term survival of the Siberian tiger and its prey species through anti-poaching activities of Inspection Tiger and non-governmental investigation teams, human-tiger conflict resolution and environmental education. To achieve effective results in anti-poaching activity Phoenix encourage the work of both governmental and public rangers. I. KHABAROVSKY AND SPECIAL EMERGENCY RESPONSE TEAMS OF INSPECTION TIGER This report will highlight the work and outputs of Khabarovsky anti-poaching team and Special Emergency Response team that cover the south of Khabarovsky region and the whole territory of Primorsky region. For the reported period, the Khabarovsky team has documented 47 cases of ecological violations; Special Emergency Response team has registered 25 conflict tiger cases. Tables 1 and 2 show the results of both teams. Conflict Tiger Cases The Special Emergency Response Team works on the territory of Primorsky region and south of Khabarovsky region. For the reported period, 25 conflict tiger cases have been registered and investigated by the Special Emergency Response team of Inspection Tiger, one of them transpired to be a “false alarm”. 1) On January 04, 2003 the Special Emergency Response team received information from gas filling station workers that in the vicinity of Terney village they had seen a tiger with a killed dog crossing Terney-Plastun route. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Assistance Series HAROLD M. JONES Interviewed by: Self Initial interview date: n/a Copyright 2002 ADST Dedicated with love and affection to my family, especially to Loretta, my lovable supporting and charming wife ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The inaccuracies in this book might have been enormous without the response of a great number of people I contacted by phone to help with the recall of events, places, and people written about. To all of them I am indebted. Since we did not keep a diary of anything that resembled organized notes of the many happenings, many of our friends responded with vivid memories. I have written about people who have come into our lives and stayed for years or simply for a single visit. More specifically, Carol, our third oldest daughter and now a resident of Boulder, Colorado contributed greatly to the effort with her newly acquired editing skills. The other girls showed varying degrees of interest, and generally endorsed the effort as a good idea but could hardly find time to respond to my request for a statement about their feelings or impressions when they returned to the USA to attend college, seek employment and to live. There is no one I am so indebted to as Karen St. Rossi, a friend of the daughters and whose family we met in Kenya. Thanks to Estrellita, one of our twins, for suggesting that I link up with Karen. “Do you use your computer spelling capacity? And do you know the rule of i before e except after c?” Karen asked after completing the first lot given her for editing. -

The Last Hunt of Jim Corbett by Joseph Jordania University of Melbourne

Presentation treatment Of the feature film The Last Hunt of Jim Corbett By Joseph Jordania University of Melbourne Logline: An aging legendary hunter-turned conservationist Jim Corbett is asked to go after a very cunning man-eating tiger that is terrorizing mountain villages and thousands of woodchoppers at the Indian-Nepalese border. The hunter finds himself trapped between the governmental intrigues and the man-eating tiger who is hunting Corbett. Genre: environmental drama-suspense I N T R O D U C T I O N This text is the result of detailed investigation of the author of the story the last hunt of the legendary hunter, conservationist and author Jim Corbett. This hunt took place in Kumaon, North India, between the small villages Chuka and Thak, next to Nepal, in October-November 1938. This is the last story of Corbett’s book “Man-Eaters of Kumaon” (1944. Oxford University Press). The book became an instant classic and bestseller. From the early 1970s, when I read this story for the first time, I was profoundly moved by its sheer dramatic, thriller-like atmosphere, where the hunter and the man-eating tiger stalk each other in the jungles and the streets of the deserted Indian village. Every bit of the story, starting with the heart-melting accidental meeting of Corbett with the future man-eating tigress with small cubs (during Corbett’s previous hunt), followed by the tragic change of the life of the tigress, caused by the poacher-inflicted wounds, attacks on humans, and then hair-rising duel of the hunter and the clever tigress, culminating in the dramatic encounter of the hunter and the tigress on the dying seconds of the daylight, was the most dramatic story I have ever read. -

A Guide to Harmful and Toxic Creatures in the Goa of Jordan

Published by the Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan. P. O. Box 831051, Abdel Aziz El Thaalbi St., Shmesani 11183. Amman Copyright: © The Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non- commercial purposes is authorized without prior written approval from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. ISBN: 978-9957-8740-1-8 Deposit Number at the National Library: 2619/6/2016 Citation: Eid, E and Al Tawaha, M. (2016). A Guide to Harmful and Toxic Creature in the Gulf of Aqaba of Jordan. The Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan. ISBN: 978-9957-8740-1-8. Pp 84. Material was reviewed by Dr Nidal Al Oran, International Research Center for Water, Environment and Energy\ Al Balqa’ Applied University,and Dr. Omar Attum from Indiana University Southeast at the United State of America. Cover page: Vlad61; Shutterstock Library All photographs used in this publication remain the property of the original copyright holder, and it should not be reproduced or used in other contexts without permission. 1 Content Index of Creatures Described in this Guide ......................................................... 5 Preface ................................................................................................................ 6 Part One: Introduction ......................................................................................... 8 1.1 The Gulf of Aqaba; Jordan ......................................................................... 8 1.2 Aqaba; -

The San Francisco Zoo Tiger Escape and Attack 3D Visualization Is Used to Reconstruct the Escape and Attack

www.plaintiffmagazine.com SEPTEMBER 2009 The San Francisco Zoo tiger escape and attack 3D visualization is used to reconstruct the escape and attack BY JORGE MENDOZA chief if it escapes” is, indeed, woven into the fabric of modern law. AND LEX EVAN A B While common sense might argue On December 25, 2007, a 243 that a 243-pound tiger would qualify as pound, four-year old Siberian tiger something “likely to do mischief if it es named Tatiana escaped its open-air capes,” the defendants argued in pretrial habitat at the San Francisco Zoo, stalked proceedings that strict liability should not and attacked three young men who were be applied to the facts of this case. In visiting the Zoo. The tragic event made The true rule of law is, that the per support of their position, the defendants headlines around the world. Brothers son who for his own purposes brings on referred to an older case where a zoo pa Kulbir and Paul Dhaliwal suffered serious his lands and collects and keeps there tron was bitten on the hand and arm injuries and their friend, Carlos Sousa, anything likely to do mischief if it es while reaching towards or into a zoo cage Jr., 17, died from his injuries. capes, must keep it in at his peril, and, while attempting to feed a polar bear. Mark Geragos represented Kulbir if he does not do so, is self evident an (McKinney v. City & County of San Francisco and Paul Dhaliwal in federal court in a swerable for all the damage which is the (1952) 109 Cal.App.2d 844, 847 [241 lawsuit naming the Zoo, the San Fran natural consequence of its escape. -

SINGLE DOSE PHARMACOKINETICS of AZITHROMYCIN in BALL PYTHONS (Python Regius)

SINGLE DOSE PHARMACOKINETICS OF AZITHROMYCIN IN BALL PYTHONS (Python regius) Rob L. Coke, DVM,1* Robert P. Hunter, MS, PhD,2 Ramiro Isaza, MS, DVM,1 James W. Carpenter, MS, DVM,1 David Koch, MS,2 and Marie Goatley, BS2 1Department of Clinical Sciences and the 2Department of Anatomy and Physiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506 USA Abstract Azithromycin is a new sub-class of macrolide antibiotics classified as an azalide. This antimicrobial has a similar mechanism of action to the other macrolides (i.e., erythromycin) by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit.2 Azithromycin provides broad-spectrum antibiosis against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria.2 It also has the ability to obtain sustained drug concentrations in tissues much greater than the corresponding plasma concentration.1,3 This study determined the pharmacokinetics of azithromycin (Zithromax®, Pfizer Inc., New York, NY 10017 USA) in ball pythons (Python regius), a species that is representative of the Boidae family. Snakes were administered azithromycin intravenously (i.v.) to determine distribution and orally (p.o.) to determine bioavailability and absorption. Seven ball pythons (two males, five females), weighing approximately 0.67-0.96 kg, were used in this experiment. Using a crossover design, each snake was given a single 10 mg/kg i.v. dose of azithromycin via cardiocentesis. For the oral study, each snake was dosed at 10 mg/kg using the same i.v. azithromycin preparation. Blood samples were collected prior to dosing and at 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hr post-azithromycin administration. -

Narratives and Adventures of Travellers in Africa

:ras3ani!iao!2!sasffiiS!i (B:t1Cibvw Duquesne ^niuirmty Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/narrativesadventOOchar TRAVELLERS IN AFRICA, if !^fP^ _(2«fe PHILADELPHIA: PORTER & COATES, Itarrafees and giducnturts Travellers in Africa. BY CHARLES WILLIAMS. Protusklt Illustrated with Enobayingb. PHILADELPHIA: PORTER & COATES. [ 'O PREFACE An intense interest has recently been awakened, and widely extended, in regard to South Africa. Questions are, in consequence, frequently arising as to the character of its surface, its diversified tribes, its plants, and its animals ; and the remarkable circvimstances under which, after long con- cealment, they have been gradually disclosed to our view. Tlxe object of the present volume is to meet such inquiries by popular details on the highest authority, abundantly interspersed with trv^ stories of chivalrous enterprise and heart-tlu-niing adventure. It respectfully solicits, therefore^ the acceptance of all ranks, and of all ages. 7» ^ ' / V A CONTENTS, CHAPTER L THE CAPE OF GOOD BOFS. PAGB Pre-eminence o? the Portuguese in Maritime Enterprise—The Fiction of Prester John—De^yitch of Covilham and Payva, by Don Pedro, the Regent— Bar- tholomew i:iaz, the Commander—The Course he pursued—Discovery of the Great Fish Xiver, and of the Cape of Storms, afterwards called the Cape of Good Hop«—Vasco de Gama—True Figure of Africa—Colonisation of the Cape by tUs Dutch—Its Cession to Great Britain—The Albatross— Cape Pigeons—The Fish of the Harbour of Cape Town .••••• 1 CHAPTER IL TABLE MODNTAIH. Appearance and Extent of the Mountain—Its two Divisions—The Devil's Moun- tain—The Lion's Head or Hill—Ascent of Table Mountain—Splendid View from its Summit— " The Spreading of the Table-Cloth "—Origin of the Name, " The Lion's Head "—Number and Daring of Lions at the early Set- tlement of the Cap»—Story of a Drunken Trumpeter— Difficult Ascent of the Lion's Head—A Night of Terror m its Neighbourhood— Shocks of Earth- inakes. -

Dana Younger Gallery

DANA YOUNGER GALLERY Book Title Artwork Title Illustrator Author Execution Date Exhibit: Mazza Collection: Past to Present Portfolio “Three Children Playing” Kate Greenaway 1880s The Fox Jumped Over the Parson’s Gate "Three Riders After the Fox" Randolph Caldecott Caldecott, Randolph 1883 A Game of Ball "A Game of Ball" Jessie Willcox Smith 1903 A Flower Wedding "Good King Henry" pg 13 Walter Cane 1905 The Brownies Latest Adventures "Brownies Move a Globe" Palmer Cox Cox, Palmer 1910 The Rover Boys at College "Playing the Piano in the Parlor" Charles Nuttall 1910 Mother Goose "Hey, Diddle Diddle" William Wallace Denslow 1910 The Wind in the Willows "Cover" Paul Bransom Grahame, Kenneth 1913 The Adventures of Peter Cottontail "Cover - color image" Harrison Cady Burgess, Thornton 1914 Stories to Tell the Littlest Ones "Visit to Mother Sun’s House", Opp. p. Willy Pogany Bryant, Sara Cone 1917 142 Anderson’s Fairy Tales "Thumbelina - Here is My Son" Helen Stratton Anderson, Hans Christian 1920 The Poppy Seed Cakes "The Goat Was Not Easy to Catch" Maud & Miska Petersham Clark, Margery 1924 The Picture-Poetry Book "Dream Time" Lois Mailou Jones McBown, Gertrude 1929 Minnie Mouse portfolio "Minnie Mouse--Model No. 1" Hardie Gramatky 1930s Raggedy Ann’s Lucky Pennies "Bye" Johhny Gruelle Gruelle, Johnny 1932 The Pied Piper of Hamelin "Rats Around Baby’s Crib" pg 15 Arthur Rackham Browning, Robert 1934 portfolio "Winter Garden" Wanda Gag 1935 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs "Let Me See Your Hands" Bill Peet Walt Disney 1937 Presents For Lupe "Bowl of Nuts" Dorothy Lathrop Lathrop, Dorothy 1940 The Wonder City of Oz "The Magician Led Number Nine Out of John R. -

Mitigating Human-Tiger Conflict: an Assessment of Compensation Payments and Tiger Removals in Chitwan National Park, Nepal

Mongabay.com Open Access Journal - Tropical Conservation Science Vol. 9 (2): 776-787, 2016 Short Communication Mitigating human-tiger conflict: an assessment of compensation payments and tiger removals in Chitwan National Park, Nepal Rajendra Dhungana1,2*, Tommaso Savini3, Jhamak Bahadur Karki4 and Sara Bumrungsri1 1Department of Biology, Ecology Program, Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai 90110, Thailand 2Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Environment Division, Singhadurbar, Kathmandu, Nepal 3Conservation Ecology Program, School of Bioresources and Technology, King Mongkut's University of Technology, Thonburi, Bangkhuntien, Bangkok 10150, Thailand 4Kathmandu Forestry College, Amarawatimarg, Koteshwor, Kathmandu, Nepal *Corresponding author. E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract Human-tiger conflict is one of the most critical issues in tiger conservation, requiring a focus on effective mitigation measures. We assessed the mitigation measures used between 2007 and 2014 in Chitwan National Park (CNP) and its buffer zone, which include: compensation payments made to human victims or their families, compensation for livestock loss through depredation, and the removal of tigers involved in conflicts. The data collected from the offices of CNP and the Buffer Zone Management Committee were triangulated during questionnaire surveys (n=83) and key informant interviews (n=13). A total compensation of US$ 93,618 ($11,702.3 per year) was paid for tiger attacks during the eight-year period. Of this, the majority (65%) was in payment for human killings, followed by payment for livestock depredations (29.3%) and for human injuries (5.7%). The payments on average covered 80.7% of medical expenses of injured persons, and 61.7% of the monetary value of killed livestock. -

Constrictor Snakes Attacks Factsheet

factsheet Texas Incidents Involving Dangerous Wild Animals Texas currently requires permits for, but does not ban big cats, bears, and some primate species. More children have been killed or injured by captive big cats in Texas than any other state, including a 3-year-old Lee County boy and 10-year-old Yorktown girl who were both killed by pet tigers and a Channelview 4-year-old who lost his arm and a 4-year-old Harris County girl who required $17,000 in plastic surgery after being mauled by big cats. Dozens of people have been injured by primates, including a teenager and an elderly woman who were both attacked by an escaped chimpanzee, a game warden who was bitten by one of several escaped pet rhesus macaque monkeys, and a pet Java macaque who sent a woman, a child, and a firefighter to the hospital after attacking and biting all three. Date Incident Location October 16, 2011 A 4-year-old boy was attacked and mauled by a 150-pound cougar who was kept as a pet Odessa, Texas by a relative. The child was standing near the cougar's cage when the animal reached out and grabbed him. The boy was taken to hospital with significant damage to the left side of his body. The cougar was seized by animal control officials and euthanized.1 October 14, 2011 One of five capuchin monkeys kept as pets escaped from a home and was on the loose Lake Hills, Texas for five days before being recaptured. The monkey reportedly attacked a dog and charged at a man, prompting three people to shoot at the animal.2,3 September 11, 2011 A game warden with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department was bitten by one of Plantersville, Texas several pet rhesus monkeys who were on the loose as a result of forced evacuations because of wildfires in the area. -

Culture and Stigma: Ethnographic Case Studies of Tiger-Widows of Sundarban Delta, India Arabinda N

Original Paper* Culture and stigma: Ethnographic case studies of tiger-widows of Sundarban Delta, India Arabinda N. Chowdhury, Ranajit Mondal, Mrinal Kanti Biswas, Arabinda Brahma Abstract. A significant proportion of the population from the villages of Sundarban, India, depends on the reserve forest resources for their livelihood. During their livelihood activities inside the forest, many forest-goers became victims of tiger attacks. Most of the forest-goers are poor people. Husbands are the only bread-earners of the family and, after their untimely accidental death; widows are thrown into extreme poverty and dire hardship. In addition to that, they are subject to social isolation because of the cultural stigma related with tiger killing in the local community. The present case studies from two mouzas (Note 1) of Indian Sundarban reflect the sufferings and continued life struggle of these ‘Tiger-widows’ (locally called Bag-Bidhoba) and different dimensions of stigma that marginalized them from the mainstream community life; the consequent negative impact on their mental health is discussed. Keywords: Tiger-widows, culture and stigma, Sundarban, human-tiger conflict, mental illness, conservation. WCPRR December 2014: 99-122. © 2014 WACP ISSN: 1932-6270 INTRODUCTION Stigma is a mark of disgrace that sets an individual or group apart. Goffman (1963) described stigma as a process based on social construction of identity. When a person or a family is labeled with stigma, they are considered as a stereotyped group, which generates negative attitude and ultimately prejudice and discrimination (enacted stigma). As a response, the person develops shame and experiences blame, helplessness and distress (felt stigma). -

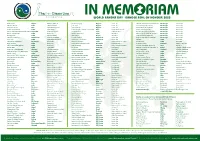

World Ranger Day I Ranger Roll of Honour 2020

WORLD RANGER DAY I RANGER ROLL OF HONOUR 2020 Alex Pajibo Liberia Death in Service Ibrahim Magaji Nigeria Homicide Héritier Ndagijimana Ndahobari DR Congo Homicide Hemant Kumar India Elephant attack John Paul Nigeria Homicide Lumumba Anuani Bihira DR Congo Homicide Shannon Barron USA Heart attack at work Simon Benku Nigeria Homicide Djamal Badi Mukandama DR Congo Homicide Sohan Singh Rawat India Tiger attack Gime Ángel Calderón Villasante Peru Heart attack at work Joseph Kasole Janvier DR Congo Homicide Maura Alejandra Hernandez Sierra Colombia Aneurism at work K. Mahendran India Elephant attack Agustin Mugisho Kulondwa DR Congo Homicide Bashir Ahmed Naik India Homicide Keshob Karmakar India Accident Jean-Louis Kambale Mutsomani DR Congo Homicide Annegowda India Elephant attack Alex Wayo Ghana Accident Jules Kambale Teremuka DR Congo Homicide Kanysh Nurtazinov Kazakhstan Killed by poachers Timothy Tembo Zimbabwe Homicide Ruphin Masumbuko Malekani DR Congo Homicide Kimo Miji India Japanese encephalitis Mabharani Chidhumo Zimbabwe Homicide Mahesh India Drowned François Kiwambisile DR Congo Homicide Sharmila Jayaram India Motor vehicle accident Shivakumar India Drowned Ajay Santosh India Drowning Maithree Wickramasinghe Sri Lanka Elephant attack Suparp Sinwan Thailand Death in service Rahul Damodhar Jadhav India Drowning Mat Kavanagh Australia Motor vehicle accident Cristian Gonzales Tanchiva Peru Covid 19 Bishan Ram India Tiger attack Bill Slade Australia Firefighting Damião Cristino de Carvahlo, Jr. Brazil Killed by illegal miners Suraiman Karemdamae Thailand Killed by poacher N’Serma Kataman Severin Benin Drowned Kan Chaiprasert Thailand Killed by poachers Mudiyanselage C K Basnayake Sri Lanka Elephant attack Elma Normandia Brazil Death in service Deepu Singh Rana India Killed by poachers Mamata Patil India Motor vehicle accident Lakhan Karmakar India Stroke while on duty Lathuram Bordoloi India Elephant attack Bienvenido ‘Toto’ Veguilla, Jr Philippines Killed by timber poachers Raúl Hernández Romero Mexico Homicide C.