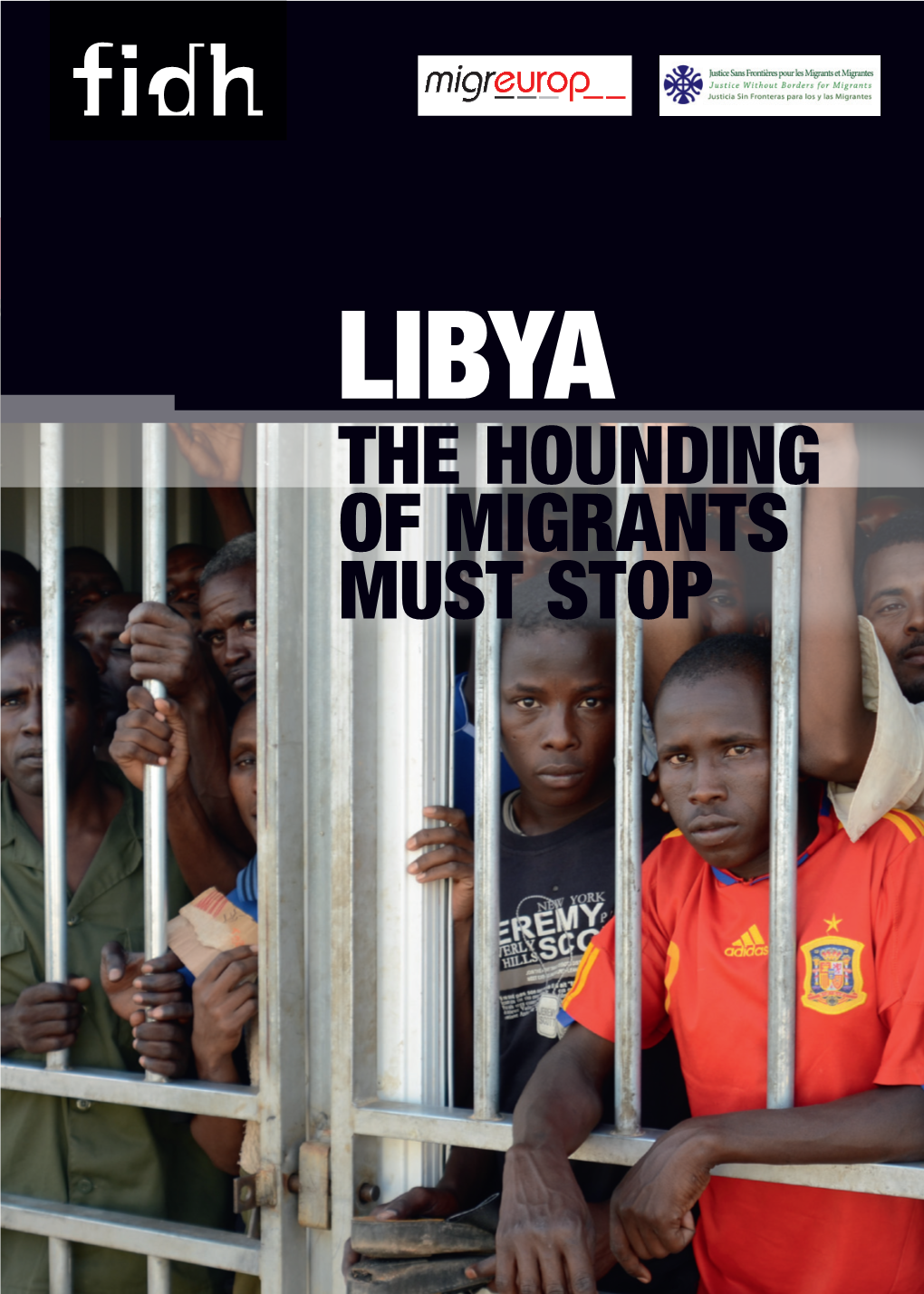

Libya: the Hounding of Migrants Must Stop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nationwide School Assessment Libya Ministry

Ministry of Education º«∏©àdGh á«HÎdG IQGRh Ministry of Education Nationwide School Assessment Libya Nationwide School Assessment Report - 2012 Assessment Report School Nationwide Libya LIBYA Libya Nationwide School Assessment Report 2012 Libya Nationwide School Assessment Report 2012 º«∏©àdGh á«HÎdG IQGRh Ministry of Education Nationwide School Assessment Libya © UNICEF Libya/2012-161Y4640/Giovanni Diffidenti LIBYA: Doaa Al-Hairish, a 12 year-old student in Sabha (bottom left corner), and her fellow students during a class in their school in Sabha. Doaa is one of the more shy girls in her class, and here all the others are raising their hands to answer the teacher’s question while she sits quiet and observes. The publication of this volume is made possible through a generous contribution from: the Russian Federation, Kingdom of Sweden, the European Union, Commonwealth of Australia, and the Republic of Poland. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the donors. © Libya Ministry of Education Parts of this publication can be reproduced or quoted without permission provided proper attribution and due credit is given to the Libya Ministry of Education. Design and Print: Beyond Art 4 Printing Printed in Jordan Table of Contents Preface 5 Map of schools investigated by the Nationwide School Assessment 6 Acronyms 7 Definitions 7 1. Executive Summary 8 1.1. Context 9 1.2. Nationwide School Assessment 9 1.3. Key findings 9 1.3.1. Overall findings 9 1.3.2. Basic school information 10 1.3.3. -

Unhcr Flash Update

UNHCR FLASH UPDATE LIBYA 21 - 27 April 2018 Highlights UNHCR is responding to the urgent humanitarian situation of around 800 Key figures: refugees and migrants who are detained in the Zwara detention centre (115 km west of Tripoli). On 25 April, UNHCR and its partner International 184,612 Libyans Medical Corps (IMC) visited the facility, provided medical assistance, and currently internally dispatched non-food items for 800 refugees and migrants in detention. UNHCR, 1 displaced (IDPs) MSF and DRC are conducting an anti-scabies campaign inside the detention 368,583 returned facility. Due to the fact that the coastal road between Zwara and Tripoli is too dangerous, in coordination with the authorities, UNHCR is exploring the IDPs (returns evacuation of all persons of concern (Eritreans, Somali and Sudanese) from registered in 2016 - Zwara to Tripoli by airplane, logistics and security permitting. March 2018)1 51,519 registered Population Movements refugees and asylum- As of 26 April 2018, 5,109 refugees and migrants were rescued/intercepted seekers in the State of by the Libyan Coast Guard (LCG). During the week, over 600 refugees and Libya2 migrants were disembarked in Tripoli (322 individuals), Zwara (111 individuals), Azzawya (82 individuals) and Al Khums (94 individuals). On the 22 April, a 9,361 persons arrived shipwreck took place near Sabratha (75 km west of Tripoli) causing the loss of in Italy by sea in 20183 at least 11 lives at sea. The remaining 82 survivors were disembarked in Azzawya. Humanitarian and medical assistance was provided by UNHCR and 451 monitoring visits its partner IMC at all disembarkation points where the most vulnerable cases to detention centres so were identified. -

1 Department of the Treasury Office of Foreign Assets

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 11/23/2011 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2011-30293, and on FDsys.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL REMOVAL FROM THE LIST OF SPECIALLY DESIGNATED NATIONALS AND BLOCKED PERSONS OF CERTAIN ENTITIES LISTED PURSUANT TO EXECUTIVE ORDER 13566 AGENCY: Office of Foreign Assets Control, Treasury. ACTION: Notice. ---------------------- SUMMARY: The Treasury Department's Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) is removing from the list of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (“SDN List”) the names of 42 entities that are listed pursuant to Executive Order 13566 of February 25, 2011, “Blocking Property and Prohibiting Certain Transactions Related to Libya.” DATES: The removal from the SDN List of the 42 entities identified in this notice is effective on November 18, 2011. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Assistant Director for Sanctions Compliance & Evaluation, tel.: 202-622-2490, Assistant Director for Licensing, tel.: 202-622-2480, Assistant Director for Policy, tel.: 202-622-4855, Office of Foreign Assets Control, or Chief Counsel (Foreign Assets Control), tel.: 202-622-2410, Office of the General Counsel, Department of the Treasury (not toll free numbers). SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Electronic and Facsimile Availability 1 This document and additional information concerning OFAC are available from OFAC’s Web site (www.treasury.gov/ofac) or via facsimile through a 24-hour fax-on-demand service, tel.: 202/622-0077. Background On February 25, 2011, the President issued Executive Order 13566, “Blocking Property and Prohibiting Certain Transactions Related to Libya” (“E.O. 13566”), pursuant to, inter alia, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (50 U.S.C. -

Refugee Policies from 1933 Until Today: Challenges and Responsibilities

Refugee Policies from 1933 until Today: Challenges and Responsibilities ihra_4_fahnen.indd 1 12.02.2018 15:59:41 IHRA series, vol. 4 ihra_4_fahnen.indd 2 12.02.2018 15:59:41 International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (Ed.) Refugee Policies from 1933 until Today: Challenges and Responsibilities Edited by Steven T. Katz and Juliane Wetzel ihra_4_fahnen.indd 3 12.02.2018 15:59:42 With warm thanks to Toby Axelrod for her thorough and thoughtful proofreading of this publication, to the Ambassador Liviu-Petru Zăpirțan and sta of the Romanian Embassy to the Holy See—particularly Adina Lowin—without whom the conference would not have been possible, and to Katya Andrusz, Communications Coordinator at the Director’s Oce of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. ISBN: 978-3-86331-392-0 © 2018 Metropol Verlag + IHRA Ansbacher Straße 70 10777 Berlin www.metropol-verlag.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten Druck: buchdruckerei.de, Berlin ihra_4_fahnen.indd 4 12.02.2018 15:59:42 Content Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust ........................................... 9 About the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) .................................................... 11 Preface .................................................... 13 Steven T. Katz, Advisor to the IHRA (2010–2017) Foreword The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, the Holy See and the International Conference on Refugee Policies ... 23 omas Michael Baier/Veerle Vanden Daelen Opening Remarks ......................................... 31 Mihnea Constantinescu, IHRA Chair 2016 Opening Remarks ......................................... 35 Paul R. Gallagher Keynote Refugee Policies: Challenges and Responsibilities ........... 41 Silvano M. Tomasi FROM THE 1930s TO 1945 Wolf Kaiser Introduction ............................................... 49 Susanne Heim The Attitude of the US and Europe to the Jewish Refugees from Nazi Germany ....................................... -

Unhcr Position on the Designations of Libya As a Safe Third Country and As a Place of Safety for the Purpose of Disembarkation Following Rescue at Sea

UNHCR POSITION ON THE DESIGNATIONS OF LIBYA AS A SAFE THIRD COUNTRY AND AS A PLACE OF SAFETY FOR THE PURPOSE OF DISEMBARKATION FOLLOWING RESCUE AT SEA UNHCR POSITION ON THE DESIGNATIONS OF LIBYA AS A SAFE THIRD COUNTRY AND AS A PLACE OF SAFETY FOR THE PURPOSE OF DISEMBARKATION FOLLOWING RESCUE AT SEA September 2020 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Situation of Foreign Nationals (Including Asylum-Seekers, Refugees and Migrants)................................... 3 Humanitarian Situation ................................................................................................................................. 11 International Protection Needs of Foreign Nationals Departing from/through Libya .................................. 16 Libya as a Country of Asylum ...................................................................................................................... 16 Designation of Libya as Safe Third Country ................................................................................................ 16 Designation of Libya as a Place of Safety for the Purpose of Disembarkation following Rescue at Sea ... 17 Introduction 1. This position supersedes and replaces UNHCR’s guidance on foreign nationals in Libya contained in the Position on Returns to Libya – Update II of September 2018; however, UNHCR guidance in relation to Libyan nationals and habitual residents as provided in the September -

International Maritime Organization Maritime

INTERNATIONAL MARITIME ORGANIZATION MARITIME KNOWLEDGE CENTRE (MKC) “Sharing Maritime Knowledge” CURRENT AWARENESS BULLETIN JANUARY 2020 www.imo.org Maritime Knowledge Centre (MKC) [email protected] www d Maritime Knowledge Centre (MKC) About the MKC Current Awareness Bulletin (CAB) The aim of the MKC Current Awareness Bulletin (CAB) is to provide a digest of news and publications focusing on key subjects and themes related to the work of IMO. Each CAB issue presents headlines from the previous month. For copyright reasons, the Current Awareness Bulletin (CAB) contains brief excerpts only. Links to the complete articles or abstracts on publishers' sites are included, although access may require payment or subscription. The MKC Current Awareness Bulletin is disseminated monthly and issues from the current and the past years are free to download from this page. Email us if you would like to receive email notification when the most recent Current Awareness Bulletin is available to be downloaded. The Current Awareness Bulletin (CAB) is published by the Maritime Knowledge Centre and is not an official IMO publication. Inclusion does not imply any endorsement by IMO. Table of Contents IMO NEWS & EVENTS ............................................................................................................................ 2 UNITED NATIONS ................................................................................................................................... 3 CASUALTIES........................................................................................................................................... -

Porisa Libya Smugglers

Smuggling Networks in Libya Nancy Porsia, Freelance journalist, March 2015 Introduction This report is based on my work as freelance journalist in Libya since 2013, during which I have often focused on the phenomena of migration across the sea and smuggling networks, and conducted extensive interviews with all actors involved – migrants, smugglers, state officials and militias. In the central Mediterranean region, Libya is one of the main transit routes for migrants; here the phenomenon acquires significant proportions since 2002 with the transit of migrants from the Horn of Africa. Since then the number of migrants flowing into Libya has gradually increased. However the previous regime used to play ‘border diplomacy’ leveraging the threat perceived by European states in relation to migration in order to bargain its power in the international arena. In this political frame the numbers of migrants in transit through Libya and heading to Europe were under control. Only in 2008 the migrants’ flow reached the peak with 37,000 migrants registered on the Italian shores. In the same year the Treaty of Friendship between Italy and Libya marked a turning point over the relations of the two countries and in 2009 the regime launched a crackdown on the smuggling business in Libya: all the factories of wooden boats along the Libyan coast were shutdown and big number of smugglers were arrested. In 2010 the number of arrivals in Italy dropped to 4400, a decrease of almost 90% in just two years. The departures massively resumed only after the outbreak of the Revolution in 2011, when the smugglers were released and pushed by the regime to cram migrants into boats and send them to Europe, as revenge on European countries support to the revolutionaries on the ground. -

BORDER SECURITY.Pdf

COMMITTEE ON THE CIVIL DIMENSION OF SECURITY (CDS) BORDER SECURITY Special Report by Lord JOPLING (United Kingdom) Special Rapporteur 134 CDS 19 E rev. 1 fin | Original: English | 12 October 2019 134 CDS 19 E rev.1 fin TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 II. LAND BORDERS: THREE HOTSPOTS ................................................................................. 1 A. US-MEXICO BORDER .................................................................................................. 1 B. THE WESTERN BALKANS ROUTE .............................................................................. 7 C. CEUTA AND MELILLA: SPANISH ENCLAVES IN NORTH AFRICA ............................. 9 III. MARITIME ROUTES: AN UPDATE ON THE SITUATION IN THE MEDITERRANEAN........ 10 IV. AIRPORT SECURITY 18 YEARS AFTER 9/11: NEW CHALLENGES ................................. 15 V. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................... 18 BIBLIOGRAPHY .................................................................................................................. 21 134 CDS 19 E rev.1 fin I. INTRODUCTION 1. In the past several years, the ability to protect the external borders of Europe has been tested by the extraordinary movement of people fleeing violence and poverty in parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. The security of borders has become a top priority for many Allies, from the United States -

UNHCR Contributions Report of the Secretary-General on Oceans And

UNHCR Contributions Report of the Secretary-General on Oceans and the Law of the Sea, Part II June 2020 1. In the absence of safer means to seek international protection, refugees and other persons under UNHCR’s mandate continued to resort to dangerous journeys by sea in many parts of the world including in the Mediterranean Sea, in the Bay of Bengal and in the Andaman Sea. They often move along migrants seeking better life using the services of smugglers and, in many instances exposing themselves to the risks of being trafficked, kidnaped for ransom purposes or subjected to unhuman and degrading treatments. During the reporting period UNHCR continued to pursue and support protection at sea, through advocacy in support of effective, cooperative and protection-sensitive approaches to search and rescue and disembarkation arrangements; through operational activities at places of disembarkation or arrival by sea; and through supporting access to asylum and other longer-term action on addressing the drivers of dangerous journeys. Mediterranean Sea 2. Between 1 September 2019 and 22 June 2020, some 71,400 refugees and migrants crossed the Mediterranean Sea to Europe, of which 20,600 did so in 2020. Nearly 60% of sea arrivals in this period were to Greece (after crossing from Turkey), with 18% each arriving to Spain (crossing from Morocco and Algeria) and Italy (primarily crossing from Libya and Tunisia). Arrivals to Europe in this period represent a 4% decrease compared to the period between September 2018 and June 2019. Many of those crossing the sea since September 2019 likely had international protection needs, supported by the fact that some 43% of sea arrivals in this period were nationals of Afghanistan and the Syrian Arab Republic. -

Search and Rescue, Disembarkation and Relocation Arrangements in the Mediterranean Sailing Away from Responsibility? Sergio Carrera and Roberto Cortinovis No

Search and rescue, disembarkation and relocation arrangements in the Mediterranean Sailing Away from Responsibility? Sergio Carrera and Roberto Cortinovis No. 2019-10, June 2019 Abstract Search and Rescue (SAR) and disembarkation of persons in distress at sea in the Mediterranean continue to fuel divisions among EU member states. The ‘closed ports’ policy declared by the Italian Ministry of Interior in June 2018, and the ensuing refusal to let NGO ships conducting SAR operations enter Italian ports, has resulted in unresolved diplomatic rows between some European governments and EU institutions, and grave violations of the human rights of people attempting to cross the Mediterranean. This paper examines how current political controversies surrounding SAR and disembarkation in the Mediterranean unfold in a policy context characterised by a ‘contained mobility’ paradigm that has materialised in the increasing penalisation of humanitarian SAR NGOs, a strategic and gradual operational disengagement from SAR activities by the EU and its member states, and the delegation of containment tasks to the Libyan coast guard (so-called ‘pullbacks’), a development that has been indirectly supported by EU institutions. These policies have contributed to substantially widen the gap in SAR capabilities in the Central Mediterranean. This research has been conducted under the ReSOMA project. ReSOMA receives funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the grant agreement 770730. The opinions expressed in this paper are attributable solely to the authors in a personal capacity and not to any institution with which they are associated, nor can they be taken in any way to reflect the views of the European Commission'. -

Captain Suvarat Magon, in Maritime Security Strategy

海幹校戦略研究 2019 年 12 月(9-2) ROLE OF THE INDIAN NAVY IN PROVIDING MARITIME SECURITY IN THE INDIAN OCEAN REGION Captain Suvarat Magon, IN Introduction India is the third largest and one of the fastest growing economies in the world today based on gross domestic product (GDP) measured in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP). India is a peninsular maritime nation straddling Indian Ocean with 7,517 km of coastline, 2.37 million square kilometers of exclusive economic zone (EEZ) encompassing 1,197 island territories in the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal and supporting world’s second largest population on a continental landmass of the seventh largest country. Consequently, India’s hunger for energy and need for resources to support rapid economic and industrial growth makes its dependence on the IOR a strategic imperative. In this environment of expansion of sea trade to far off and diverse shores kissed by waters of the Indian Ocean and beyond, competition with other powers to fulfill the ever-growing needs of own population and the corresponding surge towards overall development, the security of the seas is likely to be a key to progress of the nation and therefore assumes critical importance especially in the prevailing environment of multifarious challenges that range from traditional at one extant to threat of piracy, terrorism, smuggling, trafficking and hybrid type to other extant. The Indian Navy’s (IN’s) 2015 Maritime Security Strategy clearly enunciates security in the IOR as an unambiguous necessity for progression of national interests and it can thus be deduced that maritime security would continue to drive the government’s policies and navy’s strategy in times to come. -

LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building LIBYA

G N I N I A R T T N E M E C R O F N E W A L LAW ENFORCEMENT TRAINING FOR CAPACITY BUILDING Co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building LIBYA Downloadable Country Booklet DL. 2.5 (Version 1.2) 1 Dissemination level: PU Let4Cap Grant Contract no.: HOME/ 2015/ISFP/AG/LETX/8753 Start date: 01/11/2016 Duration: 33 months Dissemination Level PU: Public X PP: Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission) RE: Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission) Revision history Rev. Date Author Notes 1.0 20/12/2017 SSSA Overall structure and first draft 1.1 23/02/2018 SSSA Second version after internal feedback among SSSA staff 1.2 10/05/2018 SSSA Final version version before feedback from partners LET4CAP_WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable_2.5 VER1.2 WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable Deliverable 2.5 Downloadable country booklets VER V.1.2 2 LIBYA Country Information Package 3 This Country Information Package has been prepared by Claudia KNERING, under the scientific supervision of Professor Andrea de GUTTRY and Dr. Annalisa CRETA. Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy www.santannapisa.it LET4CAP, co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union, aims to contribute to more consistent and efficient assistance in law enforcement capacity building to third countries. The Project consists in the design and provision of training interventions drawn on the experience of the partners and fine-tuned after a piloting and consolidation phase.