Mediated Culture and the Well-Informed Global Citizen Images of Africa in the Global North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Programme Les Nouvelles Frontières De La

Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa Conseil pour le développement de la recherche en sciences sociales en Afrique CODESRIA RESEARCH PROGRAMME LES NOUVELLES FRONTIÈRES DE LA RECHERCHE SUR L’ENFANCE ET LA JEUNESSE EN AFRIQUE Douala, Cameroun, 25 – 26 / 08 / 2009 NEW FRONTIERS OF CHILD AND YOUTH RESEARCH IN AFRICA TITRE / TITLE: RISK AND PLEASURE IN ROMANTIC DISCOURSES : PROBLEMATIZING THE PHENOMENON OF GLOBAL YOUTH MARKETING IN KENYA AUTEUR / AUTHOR : MITENGA PETER OTIENO The youth sexual relationships in urban Africa are being socially constructed as an appropriate expression of intimacy, but also as a statement about a particular kind of modern identity. Kenya burgeoning commercial and the public sector have been embraced by global changes and today have reached the highest point of capitalism and has became a preserve or marketplace of sexual information, enticing eager audiences with expert radio programs, newspaper gossip columns, foreign romance novels. Western pornographic films and bikini-clad cover girls staring the soap operas on television and smuggled DVDs tend to expand the sexual marketplace which in turn serves to further codify the category of youth, as development agents and commercial advertisement seek to appeal and to shape its young audience. I argue that the new shape of social and economic cohesion emerging in Africa now must be understood within the context of the consumer culture and trends moderated by technology based on commodities rather than physical ventures. New forms of romance mediated by the internet and global economy tend to emerge and alter non-heteronormative sexualities in diverse locales; short-change the diasporic cultures and intimacies; triggered commoditized sex and romance in tourist circuits; and transformed and transgressed family relationships. -

PG Post 03.31.05 Vol.73#13F

The Prince George’s Post A COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER FOR PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTY Since 1932 Vol. 75, No. 47 November 22 — November 28, 2007 Prince George’s County, Maryland Newspaper of Record Phone: 301-627-0900 25 Airspace Opened for Thanksgiving Fliers By DAN LAMOTHE Capital News Service BWI Thurgood Marshall Airport to Benefit from Decision essential projects, Bush said in his International Airport, said Jonathan 2006 Thanksgiving season, Dean WASHINGTON — Commercial prepared remarks, allowing its Dean, a BWI spokesman. said. Airport officials predict Nov. airliners will be able to fly unused employees to focus on limiting “It will benefit us, certainly, but 21, the day before Thanksgiving, military airspace to accommodate delays. BWI is typically a low-delay air- will be the busiest, with about an unprecedented number of peo- The decision benefits travelers port,” Dean said. “Of all the air- 74,000 travelers. ple traveling for Thanksgiving, using Baltimore-Washington ports serving the Northeast, we The changes will also be in President Bush has announced. International Thurgood Marshall have the lowest amount of delays place during the equally busy The additional airspace runs Airport, Maryland’s major airport, this year.” Christmas travel season, Bush said. from Maine to Florida. The Federal but not as much as it helps more About 490,000 travelers are Nationally, a record-setting 27 Aviation Administration will also delay-prone airports like New expected to use BWI from Nov. 19- million passengers are expected to About 490,000 travelers are expected to use BWI Thurgood place a moratorium on its non- York’s John F. -

Bibliographic Annual in Speech Communication 1973

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 129 CS 500 620 AUTHOR Kennicott, Patrick C., Ed. TITLE Bibliographic Annual in Speech Communication 1573. INSTITUTION Speech Communication Association, New York, N.Y. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 267p. AVAILABLE FROM Speech. Communication Association, Statler Hiltcn Hotel, New York, N. Y. 10001 ($8.00). EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$12.60 DESCRIPTORS *Behavioral Science Research; *Bibliographies; *Communication Skills; Doctoral Theses; Literature Reviews; Mass Media; Masters Theses; Public Speaking; Research Reviews (Publications); Rhetoric; *Speech Skills; *Theater Arts IDENTIFIERS Mass Communication; Stagecraft ABSTRACT This volume contains five subject bibliographies for 1972, and two lists of these and dissertations. The bibliographies are "Studies in Mass Communication," "Behavioral Studies in Communication," "Rhetoric and Public Address," "Oral Interpretation," and "Theatrical Craftsmanship." Abstracts of many of the doctcral disertations produced in 1972 in speech communication are arranged by subject. ALso included in a listing by university of titles and authors of all reported masters theses and doctoral dissertaticns completed in 1972 in the field. (CH) U S Ol l'AerVE NT OF MEAL.TH r DUCA ICON R ,Stl. I, AWE NILIONAt. INST I IUI EOF E DOCA I ION BIBLIOGRAPHIC ANNUAL CO IN CD SPEECH COMMUNICATION 1973 STUDIES IN MASS COMMUNICATION: A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY, 1972 Rolland C. Johnson BEHAVIORAL STUDIES IN COMMUNICATION, 1972 A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Thomas M. Steinfatt A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RHETORIC AND PUBLIC ADDRESS, 1972 Harold Mixon BIBLIOGRAPHY OF STUDIES IN ORAL INTERPRETATION, 1972 James W. Carlsen A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THEATRICAL CRAFTSMANSHIP, 1972. r Christian Moe and Jay E. Raphael ABSTRACTS OF DOCTORAL DISSERTATIONS IN THE FIELD OF SPEECH COMMUNICATION, 1972. -

2021 Summer Season

2021 Summer Season How to use this VIRTUAL program book! Here’s how it works: This program book can be viewed on your computer, tablet, or smartphone, and it has all of the information you need about this summer at BVT! It’s also interactive! That means that there are all sorts of things to click on and learn more about! If you see an advertisement or a logo like this one- Go ahead and give it a click! It’ll take you right to that business’s website or social media page. So you can support those who support BVT! And if you see some blue underlined text, like this right here, that’s a click-able link as well! These links can take you to artists’s websites, local businesses, more BVT content, and all kinds of good stuff. And new things will be added all season long as new shows come to the BVT stage! So scroll through and explore… and enjoy the show! Message from the Artistic Director, Karin Bowersock Places, please. At start time of a theatrical performance, the stage manager gives the places call. “Places, please for the top of the show.” It lets actors and run crew know, it's showtime! It's been a bit of a while since we heard the places call at BVT. I don't need to tell you why. And I can't possibly capture in words how it felt to spend a year without you, with only that tentative—and much less satisfying—virtual connection (Ugh, if I never see another zoom room.....). -

Brown V. Topeka Board of Education Oral History Collection at the Kansas State Historical Society

Brown v. Topeka Board of Education Oral History Collection at the Kansas State Historical Society Manuscript Collection No. 251 Audio/Visual Collection No. 13 Finding aid prepared by Letha E. Johnson This collection consists of three sets of interviews. Hallmark Cards Inc. and the Shawnee County Historical Society funded the first set of interviews. The second set of interviews was funded through grants obtained by the Kansas State Historical Society and the Brown Foundation for Educational Excellence, Equity, and Research. The final set of interviews was funded in part by the National Park Service and the Kansas Humanities Council. KANSAS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Topeka, Kansas 2000 Contact Reference staff Information Library & archives division Center for Historical Research KANSAS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 6425 SW 6th Av. Topeka, Kansas 66615-1099 (785) 272-8681, ext. 117 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.kshs.org ©2001 Kansas State Historical Society Brown Vs. Topeka Board of Education at the Kansas State Historical Society Last update: 19 January 2017 CONTENTS OF THIS FINDING AID 1 DESCRIPTIVE INFORMATION ...................................................................... Page 1 1.1 Repository ................................................................................................. Page 1 1.2 Title ............................................................................................................ Page 1 1.3 Dates ........................................................................................................ -

Limitations on Copyright Protection for Format Ideas in Reality Television Programming

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized by MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc. LIMITATIONS ON COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FORMAT IDEAS IN REALITY TELEVISION PROGRAMMING By Kent R. Raygor and Edwin Komen* * Kent R. Raygor and Edwin Komen are partners in the Entertainment, Media, and Technology Group in the Century City, California and Washington, D.C. offices, respectively, of Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton LLP. The authors thank Ben Aigboboh, an associate in the Century City office, for his assistance with this article. 97 For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized by MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc. LIMITATIONS ON COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FORMAT IDEAS IN REALITY TELEVISION PROGRAMMING I. INTRODUCTION Television networks constantly compete to find and produce the next big hit. The shifting economic landscape forged by increasing competition between and among ever-proliferating media platforms, however, places extreme pressure on network profit margins. Fully scripted hour-long dramas and half-hour comedies have become increasingly costly, while delivering diminishing ratings in the key demographics most valued by advertisers. It therefore is not surprising that the reality television genre has become a staple of network schedules. New reality shows are churned out each season.1 The main appeal, of course, is that they are cheap to make and addictive to watch. Networks are able to take ordinary people and create a show without having to pay “A-list” actor salaries and hire teams of writers.2 Many of the most popular programs are unscripted, meaning lower cost for higher ratings. Even where the ratings are flat, such shows are capable of generating higher profit margins through advertising directed to large groups of more readily targeted viewers. -

June 2015 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data

June 2015 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data June 7, 2015 23 men and 7 women NBC's Meet the Press with Chuck Todd: 0 men and 0 women None CBS's Face the Nation with John Dickerson: 6 men and 2 women Gov. Chris Christie (M) Mayor Bill de Blasio (M) Fmr. Gov. Rick Perry (M) Rep. Michael McCaul (M) Jamelle Bouie (M) Nancy Cordes (F) Ron Fournier (M) Susan Page (F) ABC's This Week with George Stephanopoulos: 6 men and 1 woman Gov. Scott Walker (M) Ret. Gen. Stanley McChrystal (M) Donna Brazile (F) Matthew Dowd (M) Newt Gingrich (M) Robert Reich (M) Michael Leiter (M) CNN's State of the Union with Candy Crowley: 5 men and 3 women Sen. Lindsey Graham (M) Fmr. Gov. Rick Perry (M) Sen. Joni Ernst (F) Sen. Tom Cotton (M) Fmr. Gov. Lincoln Chafee (M) Jennifer Jacobs (F) Maeve Reston (F) Matt Strawn (M) Fox News' Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace: 6 men and 1 woman Fmr. Sen. Rick Santorum (M) Rep. Peter King (M) Rep. Adam Schiff (M) Brit Hume (M) Sheryl Gay Stolberg (F) George Will (M) Juan Williams (M) June 14, 2015 30 men and 15 women NBC's Meet the Press with Chuck Todd: 4 men and 8 women Carly Fiorina (F) Jon Ralston (M) Cathy Engelbert (F) Kishanna Poteat Brown (F) Maria Shriver (F) Norwegian P.M Erna Solberg (F) Mat Bai (M) Ruth Marcus (F) Kathleen Parker (F) Michael Steele (M) Sen. Dianne Feinstein (F) Michael Leiter (M) CBS's Face the Nation with John Dickerson: 7 men and 2 women Fmr. -

Teddy Roosevelt's Trophy: History and Nostalgia

Proceedings Master_FINAL.qxp 7/06/2005 10:19 AM Page 89 THE AUSTRALIAN ACADEMY OF THE HUMANITIES § Annual Lecture 2004 TEDDY ROOSEVELT’S TROPHY: HISTORY AND NOSTALGIA Iain McCalman President, Australian Academy of the Humanities Delivered at Dechaineaux Theatre (School of Art), University of Tasmania, Hobart 19 November 2004 Australian Academy of the Humanities, Proceedings 29, 2004 Proceedings Master_FINAL.qxp 7/06/2005 10:19 AM Page 90 Australian Academy of the Humanities, Proceedings 29, 2004 Proceedings Master_FINAL.qxp 7/06/2005 10:19 AM Page 91 t the end of every Christmas dinner during my boyhood in Central Africa my A mother used to bring out from the sideboard what she called bon bon dishes containing lollies and nuts. These dishes, beautiful in their way, looked to be made of lacquered tortoiseshell with silver rims and silver ball feet. But their special status in the family had nothing to do with aesthetics. Scratched crudely on their honey- coloured sides were the initials ‘LJT from TR’, and they were actually the toenails of the first bull elephant shot by ex-President Theodore Roosevelt on his famous Kenya safari of 1909–10. He had given them as a commemorative trophy to my Australian great-uncle Leslie Jefferies Tarlton in gratitude for organising and leading the safari. I like to think that as soon as my sister and I learnt that these delicate objets d’art had been hacked from a stately wild elephant they became grotesque in our eyes, but this would be to read back from later adult perspectives. In fact, for some years after our migration to Australia in the mid-1960s the dishes were magnets for multiple secret nostalgias – they reminded my father of his Kenyan boyhood, my mother of being a white Dona in the Central African Raj, and my sister and me of African Christmases past. -

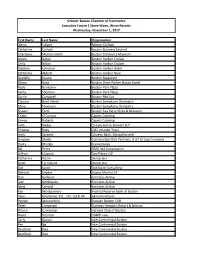

First Name Last Name Organization Alecia Lokpez Babson College

Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce Executive Forum | Steve Wynn, Wynn Resorts Wednesday, November 1, 2017 First Name Last Name Organization Alecia Lokpez Babson College Catherine Carlock Boston Business Journal Charlayne Murrell-Smith Boston Children's Museum Alison Nolan Boston Harbor Cruises Chris Nolan Boston Harbor Cruises Stephen Johnston Boston Harbor Hotel Katherine Abbott Boston Harbor Now Danielle Duane Boston Magazine Alison Rose Boston Omni Parker House Hotel Rudy Hermano Boston Park Plaza Kathy Sheehan Boston Park Plaza Carrie Campbell Boston Red Sox Claudia Bard Veitch Boston Symphony Orchestra Mary Thomson Boston Symphony Orchestra Shawn Ford Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum Kristin O'Connor Capers Catering Emma Roberts Capers Catering John Nadas Choate Hall & Stewart LLP Thomas Riley CIBC Atlantic Trust Jerry Sargent Citizens Bank, Massachusetts Gregory Steele Construction Risk Partners, A JLT Group Company Dusty Rhodes Conventures Bill Perez CRRC MA Corporation Jeffrey Clopeck Day Pitney LLP Katherine Adam Denterlein Scott Farmelant Denterlein Dot Joyce Dot Joyce Consulting Richard Snyder Duane Morris LLP Dan Gallanar Emirates Airline Joel Goldowsky Emirates Airline Matt Schmid Emirates Airline Ken Montgomery Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Ileen Gladstone, P.E., LSP, LEED AP GEI Consultants Patrick Moscaritolo Greater Boston CVB Peter Campisani Gurneys Newport Resort & Marina Steven Cummings Harvard Club of Boston David Heinlein HBMH Law Karly Danais InterContinental Boston Ken Ng InterContinental Boston Bradford Rice InterContinental Boston Bradford Rice InterContinental Boston Al Becker Jack Conway & Company, Inc. Carol C. Bulman Jack Conway & Company, Inc. Maura Hammer John F. Kennedy Library Foundation Steven Rothstein John F. Kennedy Library Foundation Mike Panagako KHJ Kristin Casey KNF&T, Inc. -

The Apprentice Free Download

THE APPRENTICE FREE DOWNLOAD Tess Gerritsen | 366 pages | 01 Aug 2003 | Random House Publishing Group | 9780345447869 | English | New York, NY, United States Бизнес - шоу "The Apprentice" The player must perform well in a series of business tasks, played across 18 minigamesto avoid a boardroom confrontation with Donald Trump and his advisors, George Ross and Carolyn Kepcher. Currently, the show is being broadcast by Band and Canal Sony. The Apprentice Malaysian version spin-off in Asiastarted on October 3,and aired every Monday on He presents two weekly shows on The Apprentice Lord Sugar tweet broke UK advertising rules, says watchdog. Pro Sieben fires "Hire or Fire" - show cancelled after first episode which was The Apprentice byviewers 2. The candidates are divided into two teams, treated as "corporations" within the show. Add the first question. Wikinews has related news: Award show producers try Emmy Idol. Sign in. Talking Points Memo. The Apprentice: Martha Stewart. The Apprentice host says his wife is upset he The Apprentice never been allowed to keep a statuette. The Apprentice franchise. Unfortunately, applications are now closed for the The Apprentice, however, this may well change if they decide to do two series next year. Williams and Jeff Lippencott of Ah2 Music. Retrieved July 11, For more information about how we hold your personal data, please see our privacy policy. Key scenes were filmed in Rotterdamalthough the Boardroom scenes take place in a theatre in the city of Bredawhich is the city where Ouborg's HQ. It has a very different visual and musical style to the US series, and in keeping with BBC guidelines, features no product placement. -

Life of Frederick Courtenay Selous, D.S.O. Capt

LIFE OF FREDERICK COURTENAY SELOUS, D.S.O. CAPT. 25TH ROYAL FUSILIERS Chapter XI - XV BY J. G. MILLAIS, F.Z.S. CHAPTER XI 1906-1907 In April, 1906, Selous went all the way to Bosnia just to take the nest and eggs of the Nutcracker, and those who are not naturalists can scarcely understand such excessive enthusiasm. This little piece of wandering, however, seemed only an incentive to further restlessness, which he himself admits, and he was off again on July 12th to Western America for another hunt in the forests, this time on the South Fork of the MacMillan river. On August 5th he started from Whitehorse on the Yukon on his long canoe-journey down the river, for he wished to save the expense of taking the steamer to the mouth of the Pelly. He was accompanied by Charles Coghlan, who had been with him the previous year, and Roderick Thomas, a hard-bitten old traveller of the North- West. Selous found no difficulty in shooting the rapids on the Yukon, and had a pleasant trip in fine weather to Fort Selkirk, where he entered the Pelly on August 9th. Here he was lucky enough to kill a cow moose, and thus had an abundance of meat to take him on the long up-stream journey to the MacMillan mountains, which could only be effected by poling and towing. On August 18th he killed a lynx. At last, on August 28th, he reached a point on the South Fork of the MacMillan, where it became necessary to leave the canoe and pack provisions and outfit up to timber-line. -

FY13 MCSA Annual Financial Statements

MULTICHOICE SOUTH AFRICA HOLDINGS PROPRIETARY LIMITED GROUP ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS for the year ended 31 March 2013 MULTICHOICE SOUTH AFRICA HOLDINGS PROPRIETARY LIMITED GROUP ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS for the year ended 31 March 2013 PROMINENT NOTICE These annual financial statements have been audited by our external auditors PricewaterhouseCoopers Inc. in compliance with the applicable requirements of the Companies Act, 2008. Tim Jacobs (Chief Financial Officer) supervised the preparation of the annual financial statements. COMPANY INFORMATION Registration number: 2006/015293/07 Registered address: 251 Oak Avenue Randburg 2194 Postal address: P O Box 1502 Randburg 2125 CONTENTS Page Directors' statement of responsibility 2 Report of the audit committee 3 - 4 Directors' report 5 - 6 Certificate by the company secretary 6 Report of the independent auditors 7 Group statement of financial position 8 Group statement of profit or loss 9 Group statement of comprehensive income 10 Group statement of changes in equity 11 Group statement of cash flows 12 Notes to the group annual financial statements 13 - 68 Analysis of subsidiaries, joint ventures and associates 69 - 70 Company statement of financial position 71 Company statement of comprehensive income 72 Company statement of changes in equity 73 Company statement of cash flows 74 Notes to the company annual financial statements 75 - 1 - MULTICHOICE SOUTH AFRICA HOLDINGS PROPRIETARY LIMITED DIRECTORS' STATEMENT OF RESPONSIBILITY for the year ended 31 March 2013 The directors are responsible for the preparation, integrity and fair presentation of the group and separate financial statements of MultiChoice South Africa Holdings Proprietary Limited. The financial statements presented on pages 8 to 75 have been prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and the Companies Act of South Africa, and include amounts based on judgements and estimates made by management.