Medication in AN: a Multidisciplinary Overview of Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyproheptadine

PATIENT & CAREGIVER EDUCATION Cyproheptadine This information from Lexicomp® explains what you need to know about this medication, including what it’s used for, how to take it, its side effects, and when to call your healthcare provider. What is this drug used for? It is used to ease allergy signs. It is used to treat hives. It may be given to you for other reasons. Talk with the doctor. What do I need to tell my doctor BEFORE I take this drug? For all patients taking this drug: If you have an allergy to cyproheptadine or any other part of this drug. If you are allergic to this drug; any part of this drug; or any other drugs, foods, or substances. Tell your doctor about the allergy and what signs you had. If you have any of these health problems: Bowel block, enlarged prostate, glaucoma, trouble passing urine, or ulcers in your stomach or bowel. If you are taking certain drugs used for depression like Cyproheptadine 1/9 isocarboxazid, phenelzine, or tranylcypromine, or drugs used for Parkinson’s disease like selegiline or rasagiline. If you are taking any of these drugs: Linezolid or methylene blue. If you are 65 or older. If you are breast-feeding. Do not breast-feed while you take this drug. Children: If your child is a premature baby or is a newborn. Do not give this drug to a premature baby or a newborn. This is not a list of all drugs or health problems that interact with this drug. Tell your doctor and pharmacist about all of your drugs (prescription or OTC, natural products, vitamins) and health problems. -

Low-Dose Doxepin for Treatment of Pruritus in Patients on Hemodialysis

DIALYSIS Low-Dose Doxepin for Treatment of Pruritus in Patients on Hemodialysis Fatemeh Pour-Reza-Gholi,1 Alireza Nasrollahi,2 Ahmad Firouzan,1 Ensieh Nasli Esfahani,1 Farhat Farrokhi3 1Department of Nephrology, Introduction. Pruritus is one of the frequent discomforting Shaheed Labbafinejad complications in patients with end-stage renal disease. We Medical Center & Urology and prospectively evaluated the effectiveness of doxepin, an H1-receptor Nephrology Research Center, antagonist of histamine, in patients with pruritus resistant to Shaheed Beheshti Medical University, Tehran, Iran conventional treatment. 2Department of Nephrology, Materials and Methods. A randomized controlled trial with a Shohada-e-Tajrish Hospital, crossover design was performed on 24 patients in whom other Shaheed Beheshti Medical etiologic factors of pruritus had been ruled out. They were assigned University, Tehran, Iran into 2 groups and received either placebo or oral doxepin, 10 mg, 3Urology and Nephrology Research Center, Shaheed twice a day for 1 week. After a 1-week washout period, the 2 groups Beheshti Medical University, were treated conversely. Subjective outcome was determined by Tehran, Iran asking the patients described their pruritus as completely improved, relatively improved, or remained unchanged/worsened. Keywords. pruritus, doxepin, Results. Complete resolution of pruritus was reported in end-stage renal disease, 14 patients (58.3%) with doxepin and 2 (8.3%) with placebo dialysis (P < .001). Relative improvement was observed in 7 (29.2%) and 4 (16.7%), respectively. Overall, the improving effect of doxepin on Original Paper pruritus was seen in 87.5% of the patients. Twelve patients (50.0%) complained of drowsiness that alleviated in all cases after 2 days in average. -

Medications That May Interfere with Skin Testing

MEDICATIONS THAT MAY INTERFERE WITH SKIN TESTING • Due to continued advances, not all medications may be listed at time of printing. • For your safety and accurate results, at each visit, please list all your current medications (including non-prescription and those prescribed elsewhere). • It is important to let us know if you are pregnant or could be pregnant. STOP THESE MEDICATIONS FIVE DAYS BEFORE SKIN TESTING: ORAL ANTIHISTAMINES: ANTIHISTAMINE NOSE SPRAYS: • Allegra (Fexofenadine) • Astelin, Astepro, Dymista (Azelastine) • Benadryl (Diphenhydramine) • Patanase (Olopatadine) • Claritin, Alavert (Loratadine) • Clarinex (Desloratadine) ANTIHISTAMINE EYE DROPS: • Xyzal (Levocetirizine) • Alaway, Claritin, Zaditor, Zyrtec (Ketotifen) • Zyrtec (Cetirizine) • Bepreve (Bepotastine) • Cyproheptadine • Elestat (Epinastine) · All over-the-counter medications for allergy, cough, cold, sleep, • Emadine (Emedastine) or nausea that include: • Lastacaft (Alcaftadine) oAcrivastine (ex. Semprex) • Livostin (Levocabastine) oAzatadine (ex. Optimine, Trinalin) • Naphcon-A, Opcon-A, Visine-A oBrompheniramine (ex. Dimetapp) (Pheniramine) oCarbinoxamine (ex. Palgic, Arbinoxa) • Optivar (Azelastine) oChlorpheniramine (ex. Actifed, Aller-chlor, Chlor- • Pataday, Patanol (Olopatadine) Trimeton, Tylenol Allergy) oDimenhydrinate (ex. Dramamine) HEARTBURN MEDICATIONS (H2 BLOCKERS): oDiphenhydramine (ex. Unisom, Sominex, • Axid (Nizatidine) Triaminic, many with “PM” in the title) • Pepcid, Tums Dual Action (Famotidine) oDoxylamine (ex. Nyquil, Unisom) • Tagament -

Decomposition Profile Data Analysis of Multiple Drug Effects Identifies

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Decomposition profle data analysis of multiple drug efects identifes endoplasmic reticulum stress‑inducing ability as an unrecognized factor Katsuhisa Morita1,2, Tadahaya Mizuno1,2* & Hiroyuki Kusuhara1* Chemicals have multiple efects in biological systems. Because their on‑target efects dominate the output, their of‑target efects are often overlooked and can sometimes cause dangerous adverse events. Recently, we developed a novel decomposition profle data analysis method, orthogonal linear separation analysis (OLSA), to analyse multiple efects. In this study, we tested whether OLSA identifed the ability of drugs to induce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress as a previously unrecognized factor. After analysing the transcriptome profles of MCF7 cells treated with diferent chemicals, we focused on a vector characterized by well‑known ER stress inducers, such as ciclosporin A. We selected fve drugs predicted to be unrecognized ER stress inducers, based on their inducing ability scores derived from OLSA. These drugs actually induced X‑box binding protein 1 splicing, an indicator of ER stress, in MCF7 cells in a concentration‑dependent manner. Two structurally diferent representatives of the fve test compounds exhibited similar results in HepG2 and HuH7 cells, but not in PXB primary hepatocytes derived from human‑liver chimeric mice. These results indicate that our decomposition strategy using OLSA uncovered the ER stress‑inducing ability of drugs as an unrecognized efect, the manifestation of which depended on the background of the cells. Small compounds have the capacity to interact with multiple cellular proteins, thereby mediating multiple efects depending on their exposure to interacting proteins. It is quite difcult to identify the full range of efects of a new chemical, even for its developers, and some factors may be unrecognized. -

Male Anorgasmia: from “No” to “Go!”

Male Anorgasmia: From “No” to “Go!” Alexander W. Pastuszak, MD, PhD Assistant Professor Center for Reproductive Medicine Division of Male Reproductive Medicine and Surgery Scott Department of Urology Baylor College of Medicine Disclosures • Endo – speaker, consultant, advisor • Boston Scientific / AMS – consultant • Woven Health – founder, CMO Objectives • Understand what delayed ejaculation (DE) and anorgasmia are • Review the anatomy and physiology relevant to these conditions • Review what is known about the causes of DE and anorgasmia • Discuss management of DE and anorgasmia Definitions Delayed Ejaculation (DE) / Anorgasmia • The persistent or recurrent delay, difficulty, or absence of orgasm after sufficient sexual stimulation that causes personal distress Intravaginal Ejaculatory Latency Time (IELT) • Normal (median) à 5.4 minutes (0.55-44.1 minutes) • DE à mean IELT + 2 SD = 25 minutes • Incidence à 2-11% • Depends in part on definition used J Sex Med. 2005; 2: 492. Int J Impot Res. 2012; 24: 131. Ejaculation • Separate event from erection! • Thus, can occur in the ABSENCE of erection! Periurethral muscle Sensory input - glans (S2-4) contraction Emission Vas deferens contraction Sympathetic input (T12-L1) SV, prostate contraction Bladder neck contraction Expulsion Bulbocavernosus / Somatic input (S1-3) spongiosus contraction Projectile ejaculation J Sex Med. 2011; 8 (Suppl 4): 310. Neurochemistry Sexual Response Areas of the Brain • Pons • Nucleus paragigantocellularis Neurochemicals • Norepinephrine, serotonin: • Inhibit libido, -

Serotonin Syndrome How to Avoid, Identify, &

Serotonin syndrome How to avoid, identify, & As the list of serotonergic agents grows, recognizing hyperthermic states and potentially dangerous drug combinations is critical to our patients’ safety. 14 Current VOL. 2, NO. 5 / MAY 2003 p SYCHIATRY Current p SYCHIATRY treat dangerous drug interactions Harvey Sternbach, MD Clinical professor of psychiatry UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute Los Angeles, CA romptly identifying serotonin syn- drome and acting decisively can keep side effects at the mild end of the spec- Ptrum. Symptoms of this potentially dangerous syndrome range from minimal in patients starting selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to fatal in those combining monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) with serotonergic agents. This article presents the latest evidence on how to: • reduce the risk of serotonin syndrome • recognize its symptoms • and treat patients with mild to life- threatening symptoms. WHAT IS SEROTONIN SYNDROME? Serotonin syndrome is characterized by changes in autonomic, neuromotor, and cognitive-behav- ioral function (Table 1) triggered by increased serotonergic stimulation. It typically results from pharmacodynamic and/or pharmacokinetic in- teractions between drugs that increase serotonin activity.1,2 continued VOL. 2, NO. 5 / MAY 2003 15 Serotonin Table 1 activity or reduced ability to How to recognize serotonin syndrome secrete endothelium-derived nitric oxide may diminish the System Clinical signs and symptoms ability to metabolize serotonin.2 Autonomic Diaphoresis, hyperthermia, hypertension, tachycardia, pupillary dilatation, nausea, POTENTIALLY DANGEROUS diarrhea, shivering COMBINATIONS Neuromotor Hyperreflexia, myoclonus, restlessness, MAOIs. Serotonin syndrome tremor, incoordination, rigidity, clonus, has been reported as a result of teeth chattering, trismus, seizures interactions between MAOIs— Cognitive-behavioral Confusion, agitation, anxiety, hypomania, including selegiline and insomnia, hallucinations, headache reversible MAO-A inhibitors (RIMAs)—and various sero- tonergic compounds. -

SELECTIVE SEROTONIN REUPTAKE INHIBITORS SEXUAL FUNCTION K. Demyttenaere0 and D. Vanderschueren" University Hospital Gasthui

* 1995 Elsevier Science B. V. All rights reserved. The Pharmacology of Sexual Function and Dysfunction J. Bancroft, editor 327 SELECTIVE SEROTONIN REUPTAKE INHIBITORS AND SEXUAL FUNCTION K. Demyttenaere0 and D. Vanderschueren" University Hospital Gasthuisberg (K.D. Leuven) ° Department of Psychiatry and Institute for Family and Sexological Sciences " Department of Endocrinology - Andrology Unit Herestraat 49 - B 3000 Leuven, Belgium dedicated to dr. Hugo De Cuyper (18.1.1946 - 13.9.1994) Introduction Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs : fluvoxamine -Floxyfral® or Fevarin®-, fluoxetine -Prozac®-, sertraline - Serlain® or Zoloft®-, paroxetine -Seroxat® or Paxil®- and citalopram -Cipramil®-) are potent and competitive inhibitors of the high affinity neuronal re-uptake mechanism for serotonin. These drugs also inhibit the re-uptake of noradrenaline and, generally to a lesser extent, dopamine, at higher concentrations. Paroxetine is the most potent serotonin uptake inhibitor in vitro of the drugs investigated, and citalopram is the most selective inhibitor of serotonin re-uptake, with paroxetine being more selective than fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and sertraline. Of the drugs investigated, only sertraline is a more potent inhibitor of dopamine compared with noradrenaline uptake. SSRIs are not only as effective as the tricyclic antidepressants in the treatment of major depression but are also effective in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, eating disorders and premenstrual syndrome (1). Although the latency of onset to therapeutic response seems to be somewhat longer, most psychiatrists consider SSRIs the initital drug of choice in the treatment of depressive disorders. Indeed, these drugs are usually better tolerated since they do not produce muscarinic, histaminic and alpha adrenergic side effects. -

Concussion Management

Concussion Management Michael Reardon, M.D. April 24,2016 Objectives • Understand what a concussion is • Know how to recognize it • Understand the differential diagnosis • Know how to manage and treat symptoms • Know when to refer for more comprehensive evaluation What is a Concussion? • Trauma to the head – Does not have to be direct blow to head • Pathophysiological Changes – Neuro-metabolic cascade • Clinical Syndrome – Signs and symptoms What Causes a Concussion? • Impact or acceleration/deceleration forces • Helmets do not prevent concussions What is a Concussion? • Pathophysiological Changes – Neuro-metabolic cascade Clinical Syndrome • Observable Signs – Loss of consciousness (only 10-15%) – Amnesia or confusion – “Dazed”, slowed down, sluggish, sleepy – Mood or Behavioral changes – Balance problems – Vomiting Clinical Syndrome • Subjective symptoms – Headache or “pressure” in head – Vision changes: blurry, fuzzy, spots/stars – Nausea – Sensitivity to light and noise – Dizziness – Feeling slowed down, like in a fog – Trouble remembering and concentrating – Irritable, anxious, or depressed mood – Sleepy or trouble sleeping Common Features of Concussion • Onset relatively immediate, though may go unrecognized • Tends to improve with rest, and worsen with exertion or over-stimulation • With good management, usually resolves over days to weeks Differential Diagnosis • Moderate to severe TBI • Non-TBI causes of symptoms – Dehydration, heat exhaustion, migraine • Side effects or complications of treatment – Deconditioning, anxiety, somnolence -

Depression After Cyproheptadine: MAO Treatment

Correspondence BIOL PSYCHIATRY 1i 77 1992;31:1172-1183 Rohrbaugh JW, Gaillard AWK (1983): Sensory and motor acetic acid levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of depressive aspects of contingent negativevariation. In Gaillard AWK, patients treated with pmbenecid. Nature 225:1259-1260. Ritter W (eds), Tutorials in ERP Research: Endogenous Van Praag HM, Kalm RS, Asnis GM, et al (1987): Den- Components. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp 269-31 I. olosization of biological psychiatry or the specificity of Swerdlow NR, Koob GF (1987): Dopamine, schizophrenia, 5-HT disturbances in psychiatric discrders. J Affective mania and depression: Toward a unified hypothesis of Disord 13:1-8. cortico-striato-pallidothalamic function. Behav Brain Sci Walter WG, Cooper R, Aldridge VJ, McCallum WC, Win- 10:197-245. ter A (1964): Contingent negative variation: An electric Tyrer P, Owen RT, Cicchetti DV (1984): The brief scale sign of ~nsori-mot.or association of expectancy in the for anxiety: A subdivision of the comprehensive psy- humaii brain Nature 203:380-384. chopathological rating scale. J Neurol Neurosurg Psy- Widl6cher D (! 983): Psychomotorretardation: Clinical, the- chiatry 47:970-975. oretical and psychometric aspects. Psychiat Clin North Van Praag HM, Korf J, Puite J (1970): 5-Hydmxyindole- Am 6:27-40. Depression after Cyproheptadine: initial evaluation. Although no actual suicide attempts were reported, he described almost constant suicidal MAO Treatment ideation, which he resisted by increasing his physical To the Editor: activity until exhaustion. Cyproheptadine has been reported to be effec- During the year prior to evaluation, he had been tive in the treatment of anorgasmia induced by the attending weekly outpatient psychotherapy. -

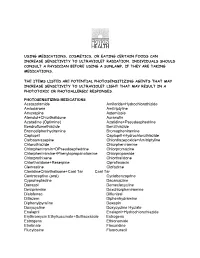

Using Medications, Cosmetics, Or Eating Certain Foods Can Increase Sensitivity to Ultraviolet Radiation

USING MEDICATIONS, COSMETICS, OR EATING CERTAIN FOODS CAN INCREASE SENSITIVITY TO ULTRAVIOLET RADIATION. INDIVIDUALS SHOULD CONSULT A PHYSICIAN BEFORE USING A SUNLAMP, IF THEY ARE TAKING MEDICATIONS. THE ITEMS LISTED ARE POTENTIAL PHOTOSENSITIZING AGENTS THAT MAY INCREASE SENSITIVITY TO ULTRAVIOLET LIGHT THAT MAY RESULT IN A PHOTOTOXIC OR PHOTOALLERGIC RESPONSES. PHOTOSENSITIZING MEDICATIONS Acetazolamide Amiloride+Hydrochlorothizide Amiodarone Amitriptyline Amoxapine Astemizole Atenolol+Chlorthalidone Auranofin Azatadine (Optimine) Azatidine+Pseudoephedrine Bendroflumethiazide Benzthiazide Bromodiphenhydramine Bromopheniramine Captopril Captopril+Hydrochlorothiazide Carbaamazepine Chlordiazepoxide+Amitriptyline Chlorothiazide Chlorpheniramine Chlorpheniramin+DPseudoephedrine Chlorpromazine Chlorpheniramine+Phenylopropanolamine Chlorpropamide Chlorprothixene Chlorthalidone Chlorthalidone+Reserpine Ciprofloxacin Clemastine Clofazime ClonidineChlorthalisone+Coal Tar Coal Tar Contraceptive (oral) Cyclobenzaprine Cyproheptadine Dacarcazine Danazol Demeclocycline Desipramine Dexchlorpheniramine Diclofenac Diflunisal Ditiazem Diphenhydramine Diphenylpyraline Doxepin Doxycycline Doxycycline Hyclate Enalapril Enalapril+Hydrochlorothiazide Erythromycin Ethylsuccinate+Sulfisoxazole Estrogens Estrogens Ethionamide Etretinate Floxuridine Flucytosine Fluorouracil Fluphenazine Flubiprofen Flutamide Gentamicin Glipizide Glyburide Gold Salts (compounds) Gold Sodium Thiomalate Griseofulvin Griseofulvin Ultramicrosize Griseofulvin+Hydrochlorothiazide Haloperidol -

High Degree of Efficacy in the Treatment of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome with Combined Co-Enzyme Q10, L-Carnitine and Amitriptyline, a Case Series Richard G Boles1,2

Boles BMC Neurology 2011, 11:102 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/11/102 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access High degree of efficacy in the treatment of cyclic vomiting syndrome with combined co-enzyme Q10, L-carnitine and amitriptyline, a case series Richard G Boles1,2 Abstract Background: Cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS), defined by recurrent stereotypical episodes of nausea and vomiting, is a relatively-common disabling and historically difficult-to-treat condition associated with migraine headache and mitochondrial dysfunction. Limited data suggests that the anti-migraine therapies amitriptyline and cyproheptadine, and the mitochondrial-targeted cofactors co-enzyme Q10 and L-carnitine, have efficacy in episode prophylaxis. Methods: A retrospective chart review of 42 patients seen by one clinician that met established CVS diagnostic criteria revealed 30 cases with available outcome data. Participants were treated on a loose protocol consisting of fasting avoidance, co-enzyme Q10 and L-carnitine, with the addition of amitriptyline (or cyproheptadine in those < 5 years) in refractory cases. Blood level monitoring of the therapeutic agents featured prominently in management. Results: Vomiting episodes resolved in 23 cases, and improved by > 75% and > 50% in three and one additional case respectively. Among the three treatment failures, two could not tolerate amitriptyline (as was also the case in the child with only > 50% efficacy) and one had multiple congenital gastrointestinal anomalies. Excluding the latter case, substantial efficacy (> 75% response) was 26/29 at the start of treatment, and 26/26 in those able to tolerate the regiment, including high dosages of amitriptyline. Conclusion: Our data suggest that a protocol consisting of mitochondrial-targeted cofactors (co-enzyme Q10 and L-carnitine) plus amitriptyline (or possibly cyproheptadine in preschoolers) coupled with blood level monitoring is highly effective in the prevention of vomiting episodes. -

Medications to Avoid Before Skin Testing

PLEASE STOP ANTIHISTAMINES 5 DAYS PRIOR TO NEW PATIENT APPOINTMENTS OR ALLERGY SKIN TESTING *Do not stop asthma medications or any other medications that do not contain antihistamine! **If you have major hives or swelling, do not stop your antihistamines. ***Please call us if you have questions about any of your medications interfering with skin testing. ****Do not use oil, cream or lotion on the back or arms for 24 hours prior to skin testing. COMMON MEDICATIONS CONTAINING ANTIHISTAMINES • Actifed (chlorpheniramine) • Elavil (amitriptyline) • Advil PM, Advil Allergy • Excedrin PM • Alavert/Claritin (loratadine) • Fexofenadine (Allegra) • Allegra (fexofenadine) • Hydroxyzine (Atarax, Vistaril) • Alka Seltzer P.M. • Imipramine (Tofranil) • Amitriptyline (Elavil) • Levocetirizine (Xyzal) • Antivert (Meclizine) • Loratadine (Claritin) • Astelin Nasal Spray (azelastine) • Meclizine (Antivert, Bonine) • Astepro Nasal Spray (azelastine) • Norpramine (desipramine) • Atarax (hydroxyzine) • Nortriptyline (Pamelor) • Azelastine nose spray (Astepro, Astelin) • Nyquil • Benadryl (diphenhydramine) • Nytol • Bonine (meclizine) • Olopatadine (Patanase nasal spray) • Cetirizine (Zyrtec) • Pamelor (nortriptyline) • Chlorpheniramine (Chlor-Trimeton, Actifed, • Patanase Nasal Spray (olopatadine) Tussionex) • PBZ (pyribenzamine) • Chlor-Trimeton (chlorpheniramine) • Pediacare • Clarinex (desloratadine) • Periactin (Cyproheptadine) • Claritin (loratadine) • Phenergan (promethazine) • Clemastine (Tavist) • Promethazine (Phenergan) • Cogentin (for Parkinson's