Exploring Regional Approaches to Drinking Water Management As a Potential Solution to Water Management Challenges in the Strait of Belle Isle, NL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Cove, Anchor Point, Flower's Cover ICSP

Integrated Community Sustainability Plan Submitted to: Department of Municipal Affairs Government of Newfoundland and Labrador PO Box 8700 St. John’s, NL A1B 4J6 Developed by: Town of Bird Cove Town of Anchor Point Town of Flower’s Cove 67 Michael’s Drive PO Box 117 PO Box 149 Bird Cove, NL Anchor Point, NL Flower’s Cove, NL A0K 1L0 A0K 1A0 A0K 2N0 Ph # 709-247-2256 Ph # 709-456-2011 Ph # 709-456-2124 Integrated Community Sustainability Plan Town of Bird Cove, Anchor Point & Flower’s Cove Table of Contents 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................................ 2 2. Collaboration / Partnership ........................................................................................................................ 5 3. Regional Assessments................................................................................................................................ 9 4. Vision - Working Toward Sustainable Communities.............................................................................. 18 5. Community Strategic Goals and Actions................................................................................................ 21 6. Pillars ...................................................................................................................................................... 22 7. Implementation, Monitoring and Evaluation.......................................................................................... 61 8. -

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador ii Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Publication Series, Newfoundland and Labrador Region No. 0008 March 2009 Revised April 2010 Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador Prepared by 1 Intervale Associates Inc. Prepared for Oceans Division, Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Branch Fisheries and Oceans Canada Newfoundland and Labrador Region2 Published by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Region P.O. Box 5667 St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1 1 P.O. Box 172, Doyles, NL, A0N 1J0 2 1 Regent Square, Corner Brook, NL, A2H 7K6 i ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011 Cat. No. Fs22-6/8-2011E-PDF ISSN1919-2193 ISBN 978-1-100-18435-7 DFO/2011-1740 Correct citation for this publication: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2011. Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador. OHSAR Pub. Ser. Rep. NL Region, No.0008: xx + 173p. ii iii Acknowledgements Many people assisted with the development of this report by providing information, unpublished data, working documents, and publications covering the range of subjects addressed in this report. We thank the staff members of federal and provincial government departments, municipalities, Regional Economic Development Corporations, Rural Secretariat, nongovernmental organizations, band offices, professional associations, steering committees, businesses, and volunteer groups who helped in this way. We thank Conrad Mullins, Coordinator for Oceans and Coastal Management at Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Corner Brook, who coordinated this project, developed the format, reviewed all sections, and ensured content relevancy for meeting GOSLIM objectives. -

The Hitch-Hiker Is Intended to Provide Information Which Beginning Adult Readers Can Read and Understand

CONTENTS: Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: The Southwestern Corner Chapter 2: The Great Northern Peninsula Chapter 3: Labrador Chapter 4: Deer Lake to Bishop's Falls Chapter 5: Botwood to Twillingate Chapter 6: Glenwood to Gambo Chapter 7: Glovertown to Bonavista Chapter 8: The South Coast Chapter 9: Goobies to Cape St. Mary's to Whitbourne Chapter 10: Trinity-Conception Chapter 11: St. John's and the Eastern Avalon FOREWORD This book was written to give students a closer look at Newfoundland and Labrador. Learning about our own part of the earth can help us get a better understanding of the world at large. Much of the information now available about our province is aimed at young readers and people with at least a high school education. The Hitch-Hiker is intended to provide information which beginning adult readers can read and understand. This work has a special feature we hope readers will appreciate and enjoy. Many of the places written about in this book are seen through the eyes of an adult learner and other fictional characters. These characters were created to help add a touch of reality to the printed page. We hope the characters and the things they learn and talk about also give the reader a better understanding of our province. Above all, we hope this book challenges your curiosity and encourages you to search for more information about our land. Don McDonald Director of Programs and Services Newfoundland and Labrador Literacy Development Council ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the many people who so kindly and eagerly helped me during the production of this book. -

Fixed Link Between Labrador and Newfoundland Pre-Feasibility Study Final Report

Fixed Link between Labrador and Newfoundland Pre-feasibility Study Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................. 1 Background and Purpose ............................................ 1 Overview of Previous Work ......................................... 1 Other Relevant Fixed Links & Tunnels Worldwide .................... 1 The Environment and Geology of the Study Area ..................... 1 Assessment of Alternative Fixed Link Concepts ..................... 2 Bridge..............................................................2 Causeway............................................................2 Tunnels.............................................................2 Comparison Summary of Alternatives..................................3 Implementation Schedule ........................................... 4 Regulatory and Environmental Issues ............................... 4 Economic and Business Case Analysis ............................... 4 Financing Considerations .......................................... 7 Conclusions ....................................................... 7 1 INTRODUCTION................................................... 8 1.1 Background and Purpose....................................... 8 1.2 Overview of Previous Work.................................... 9 1.3 Study Approach.............................................. 10 2 REVIEW OF RELEVANT FIXED LINKS WORLDWIDE...................... 12 2.1 Øresund Link............................................... -

ROUTING GUIDE - Less Than Truckload

ROUTING GUIDE - Less Than Truckload Updated December 17, 2019 Serviced Out Of City Prov Routing City Carrier Name ABRAHAMS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADAMS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADEYTON NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADMIRALS BEACH NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADMIRALS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ALLANS ISLAND NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AMHERST COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ANCHOR POINT NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ANGELS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point APPLETON NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AQUAFORTE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ARGENTIA NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ARNOLDS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ASPEN COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ASPEY BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AVONDALE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACK COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACK HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACON COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BADGER NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BADGERS QUAY NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAIE VERTE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAINE HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAKERS BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARACHOIS BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARENEED NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARR'D HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARR'D ISLANDS NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARTLETTS HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAULINE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAULINE EAST NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY BULLS NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY DE VERDE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY L'ARGENT NL TORONTO, ON -

Tap Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland and Labrador Physical Parameters and Major Ions

Department of Municipal Affairs Tap Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland and Labrador and Environment Physical Parameters and Major Ions Serviced Area(s) Source Name Sample Date Alkalinity Colour Conductivity Hardness pH TDS TSS Turbidity Boron Bromide Calcium Chloride Fluoride Potassium Sodium Sulphate Units mg/L TCU µS/cm mg/L mg/L mg/L NTU mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L 15 6.5 - 8.5 500 1.0 5.0 250 1.5 200 500 Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality Aesthetic (A) or Contaminant (C) Parameter A A A C C A C A A Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook Nov 07, 2018 99.00 20 245.0 99.00 7.79 159 0.40 LTD LTD 20.00 18 LTD LTD 8 2 Appleton Appleton (+Glenwood) Gander Lake (The Outflow) Nov 20, 2018 LTD 31 36.0 2.00 6.18 23 0.20 LTD LTD 1.00 6 LTD LTD 2 LTD Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond Nov 01, 2018 LTD 53 69.0 LTD 6.11 45 0.60 LTD LTD LTD 15 LTD LTD 11 1 Arnold's Cove Arnold's Cove Steve's Pond (2 Intakes) Nov 09, 2018 22.00 24 83.0 5.00 7.06 54 0.70 LTD LTD 2.00 11 LTD LTD 11 1 Avondale Avondale Lee's Pond Dec 03, 2018 12.00 9 86.0 7.00 7.19 56 0.40 LTD LTD 3.00 15 LTD LTD 10 1 Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond Dec 04, 2018 LTD 20 34.0 5.00 5.78 22 1.00 LTD LTD 2.00 6 LTD LTD 2 1 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond Dec 13, 2018 LTD 35 66.0 9.00 6.11 43 0.30 LTD LTD 2.00 16 LTD LTD 7 2 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as Castors Dec 05, 2018 98.00 37 264.0 107.00 7.96 172 0.20 LTD LTD 23.00 22 LTD LTD 12 3 River North) Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Sugarloaf Hill Pond -

The Transition from the Migratory to the Resident Fishery in the Strait of Belle Isle*

PATRICIA THORNTON The Transition from the Migratory to the Resident Fishery in the Strait of Belle Isle* THE EVOLUTION OF THE MERCHANT COLONIAL system in Newfoundland from migratory ship fishery to permanent resident fishery was a process which was repeated several times over the course of the colony's history, as frontier conditions retreated before the spread of settlement. On the east coast, the transition from a British-based shore fishery operated by hired servants to one in which merchants became suppliers and marketers for Newfoundland fishing families took place in the second half of the 18th century. Further north and on the south coast the migratory fishery persisted longer,1 but it was only in the Strait of Belle Isle that it held sway from its inception in the 1760s until well into the 1820s. Then here too it was slowly transformed into a resident fishery as migratory personnel became residents of the shore, with the arrival of settlers from Conception and Trinity Bays and merchants and traders from St John's and Halifax. Gerald Sider has provided an integrated and provocative conceptual framework within which to view this transformation. Three aspects of his thesis will be examined here. First, he states that the English merchants, controlling the migratory fishery throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, opposed permanent settlement and landed property. Second, he claims that in the face of settlement in the first four decades of the 19th century, the merchants reacted by getting out of the fishing business and entrapping the resident fishermen in a cashless truck system, a transition from wages to truck which, he claims, represented a loss to the fishermen and which had to be forcibly imposed by the courts. -

Census of Municipalities in Newfoundland and Labrador 2007

CENSUS OF MUNICIPALITIES in Newfoundland and Labrador 2007 Community Cooperation Resource Centre The 2007 Municipal Census of Newfoundland and Labrador was compiled by: Kelly Vodden Ryan Lane Matthew Beck With funding support provided by: The Canadian Rural Revitalization Foundation, Canada - Newfoundland and Labrador Labour Market Development Agreement, Newfoundland and Labrador - Canada Gas Tax Agreement Table Of Contents Introduction Executive Summary……………………………………………………….…………. i Highlights…………………………………………………………………………….. iv Census Tables Staff and Council…………………………………………………………………….. 1 Cooperative Initiatives……………………………………………………………… 16 Financial/Taxation Issues…………………………………………………………… 32 Office Equipment/Technology……………………………………………………… 41 Services………………………………………………………………………………… 44 Equipment……………………………………………………………………………… 55 Infrastructure…………………………………………………………………………... 58 Regulation……………………………………………………………………………… 61 Policy and Procedures………………………………………………………………. 62 Training……………………………………………………………………………… 63 Other…………………………………………………………………………………… 66 Appendices 2007 Census Questions…………………………………………….……………….. Appendix A Alphabetical list of Municipalities in NL…………………………………………….. Appendix B 2007 Census of Municipalities in Newfoundland and Labrador Executive Summary The second Census of Municipalities in Newfoundland and Labrador was conducted in the spring and summer of 2007. The census questions were divided into and are reported on in the following sections: Staff, Mayor and Council, Regional Cooperation, Financial/Taxation Issues, Office -

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | 0 | P | Q-R | S | T | U-V | W | X-Y-Z A Abraham's Cove Adams Cove, Conception Bay Adeytown, Trinity Bay Admiral's Beach Admiral's Cove see Port Kirwan Aguathuna Alexander Bay Allan’s Island Amherst Cove Anchor Point Anderson’s Cove Angel's Cove Antelope Tickle, Labrador Appleton Aquaforte Argentia Arnold's Cove Aspen, Random Island Aspen Cove, Notre Dame Bay Aspey Brook, Random Island Atlantic Provinces Avalon Peninsula Avalon Wilderness Reserve see Wilderness Areas - Avalon Wilderness Reserve Avondale B (top) Baccalieu see V.F. Wilderness Areas - Baccalieu Island Bacon Cove Badger Badger's Quay Baie Verte Baie Verte Peninsula Baine Harbour Bar Haven Barachois Brook Bareneed Barr'd Harbour, Northern Peninsula Barr'd Islands Barrow Harbour Bartlett's Harbour Barton, Trinity Bay Battle Harbour Bauline Bauline East (Southern Shore) Bay Bulls Bay d'Espoir Bay de Verde Bay de Verde Peninsula Bay du Nord see V.F. Wilderness Areas Bay L'Argent Bay of Exploits Bay of Islands Bay Roberts Bay St. George Bayside see Twillingate Baytona The Beaches Beachside Beau Bois Beaumont, Long Island Beaumont Hamel, France Beaver Cove, Gander Bay Beckford, St. Mary's Bay Beer Cove, Great Northern Peninsula Bell Island (to end of 1989) (1990-1995) (1996-1999) (2000-2009) (2010- ) Bellburn's Belle Isle Belleoram Bellevue Benoit's Cove Benoit’s Siding Benton Bett’s Cove, Notre Dame Bay Bide Arm Big Barasway (Cape Shore) Big Barasway (near Burgeo) see -

Public Health Nurses Grenfell

LABRADOR~ PUBLIC HEALTH NURSES GRENFELL PUBLIC HEALTH NURSES PHONE FAX Happy Valley-Goose Bay 897-2243/2114/2329 896-5415 Port Hope Simpson, Charlottetown, Norman Bay, 960-0271 Ext: 229 960-0461 Pinsent’s Arm, William’s Harbour Mary’s Harbour, St Lewis, Lodge Bay 921-6228 921-6975 L’Anse au Clare, Forteau, English Point, L’Anse Amour, L’Anse au Loup, West St. Modest, 931-2450 Ext: 237 931-2000 Capstan Island, Pinware, Red Bay St. Anthony East, Goose Cove, St. Anthony Bight, St. Carol’s, Great Brehat, Raleigh, Ship Cove, 454-0362 454-2163 Cook’s Harbour, Boat Harbour St. Anthony West, St. Lunaire-Griquet, Gunner’s Cove, Noddy Bay, Quirpon, 454-0290 454-2163 Straitsview, Hay Cove, L’Anse au Meadows Bide Arm, Englee, Main Brook 457-2215 Ext: 231 457-2214 Roddickton, Conche, St. Julien’s, Croque 457-2215 Ext: 233 457-2214 Eddies Cove East, Green Island Cove, Lower Cove, Green Island Brook, Pines Cove, Shoal Cove East, Sandy Cove, Savage Cove, Nameless Cove, Flower’s Cove, Bear Cove, Deadman’s Cove, Anchor Point, Blue Cove, 456-2401 456-2562 St. Barbe, Pigeon Cove, Black Duck Cove, Plum Point, Pond Cove, Brig Bay, Bird Cove, Reefs Harbour, New Ferrole, Shoal Cove West Labrador City/Wabush 285-8347/8319/8316 944-3722 Churchill Falls 925-3377 925-3380 North West River 497-8824 497-8521 Cartwright 938-7306 938-7286 Black Tickle 471-8872 471-8893 Sheshatshiu 497-3833/3837 BREASTFEEDING SUPPLIES + PUMP RENTALS: Lawtons Home Health www.lawtons.ca/home-healthcare/home-medical-supplies/breastfeeding • Dr. -

Geological Guide to the Bird Cove Region, Great Northern Peninsula

Author’s Address I. Knight W.D. Boyce Department of Natural Resources Department of Natural Resources Geological Survey Geological Survey P.O. Box 8700 P.O. Box 8700 St. John’s, NL, A1E 2H7 St. John’s, NL, A1E 2H7 Tel. 709-729-4119 Tel. 709-729-2163 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] NOTE Open File reports and maps issued by the Geological Survey Division of the Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Natural Resources are made available for public use. They have not been formally edited or peer reviewed, and are based upon preliminary data and evaluation. The purchaser agrees not to provide a digital reproduction or copy of this product to a third party. Derivative products should acknowledge the source of the data. DISCLAIMER The Geological Survey, a division of the Department of Natural Resources (the “authors and publish- ers”), retains the sole right to the original data and information found in any product produced. The authors and publishers assume no legal liability or responsibility for any alterations, changes or misrep- resentations made by third parties with respect to these products or the original data. Furthermore, the Geological Survey assumes no liability with respect to digital reproductions or copies of original prod- ucts or for derivative products made by third parties. Please consult with the Geological Survey in order to ensure originality and correctness of data and/or products. SAFETY CAUTION Many of the localities discussed in this guide can be visited along roadsides, in quarries and along the shore. In each case, care should be exercised to avoid injury by moving vehicles, falling rocks (use hard hats if possible in quarries) and rough seas. -

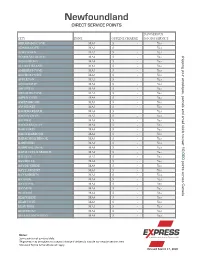

Newfoundland DIRECT SERVICE POINTS

Newfoundland DIRECT SERVICE POINTS DANGEROUS CITY ZONE OFFLINE CHARGE GOODS SERVICE ABRAHAMS COVE MA4 $ - Yes ADAMS COVE MA3 $ - Yes ADEYTOWN MA3 $ - Yes ADMIRALS BEACH MA4 $ - Yes shipping your envelopes, parcels and small skids to over AGUATHUNA MA4 $ - Yes ALLANS ISLAND MA3 $ - Yes AMHERST COVE MA3 $ - Yes ANCHOR POINT MA4 $ - Yes APPLETON MA3 $ - Yes AQUAFORTE MA4 $ - Yes ARGENTIA MA4 $ - Yes ARNOLDS COVE MA3 $ - Yes ASPEN COVE MA4 $ - Yes ASPEY BROOK MA3 $ - Yes AVONDALE MA3 $ - Yes BACK HARBOUR MA4 $ - Yes BACON COVE MA3 $ - Yes BADGER MA4 $ - Yes BADGERS QUAY MA4 $ - Yes BAIE VERTE MA4 $ - Yes BAINE HARBOUR MA4 $ - Yes BARACHOIS BROOK MA4 $ - Yes BARENEED MA3 $ - Yes BARRD ISLANDS MA4 $ - Yes 10,000 BARTLETTS HARBOUR MA4 $ - Yes BAULINE MA3 $ - Yes BAY BULLS MA4 $ - Yes points across Canada BAY DE VERDE MA4 $ - Yes BAY L'ARGENT MA4 $ - Yes BAY ROBERTS MA3 $ - Yes BAYSIDE MA4 $ - Yes BAYTONA MA4 $ - Yes BAYVIEW MA4 $ - Yes BEACHES MA4 $ - Yes BEACHSIDE MA4 $ - Yes BEAR COVE MA4 $ - Yes BEAU BOIS MA3 $ - Yes BEAUMONT MA4 $ - Yes BELL ISLAND FRONT MA4 $ - Yes Notes: Some points not serviced daily. Shipments may be subject to a beyond charge if delivery is outside our regular service area. Standard Terms & Conditions will apply. Revised March 17, 2020 Newfoundland DIRECT SERVICE POINTS DANGEROUS CITY ZONE OFFLINE CHARGE GOODS SERVICE BELL ISLAND MA4 $ - Yes BELLBURNS MA4 $ - Yes BELLEORAM MA4 $ - Yes BELLEVUE MA4 $ - Yes shipping your envelopes, parcels and small skids to over BELLMANS COVE MA4 $ - Yes BENOITS COVE MA4 $ - Yes BENTON