IN EUROPE with Special Reference to Underground Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infiltration Trench

APPENDIX F Alternative Stormwater Treatment Control Measure Fact Sheets Appendix F – Alternative Stormwater Treatment Control Measure Fact Sheets Table of Contents LID-1: Infiltration Basin ................................................................................................. F-1 LID-2: Infiltration Trench ............................................................................................. F-10 LID-3: Dry Well ........................................................................................................... F-18 T-1: Stormwater Planter ............................................................................................. F-26 T-2: Tree-Well Filter ................................................................................................... F-36 T-3: Sand Filter .......................................................................................................... F-45 T-4: Vegetated Swales ............................................................................................... F-55 T-5: Proprietary Stormwater Treatment Control Measures ......................................... F-67 HM-1: Extended Detention Basin ............................................................................... F-72 HM-2: Wet Pond ........................................................................................................ F-86 June 2015 F-i LID-1: Infiltration Basin Description An infiltration basin is a shallow earthen basin constructed in naturally permeable soil designed for retaining and -

3.1 Infiltration Basin

3.1 INFILTRATION BASIN Type of BMP LID ‐ Infiltration Treatment Mechanisms Infiltration, Evapotranspiration (when vegetated), Evaporation, and Sedimentation Maximum Treatment Area 50 acres Other Names Bioinfiltration Basin Description An Infiltration Basin is a flat earthen basin designed to capture the design capture volume, VBMP. The stormwater infiltrates through the bottom of the basin into the underlying soil over a 72 hour drawdown period. Flows exceeding VBMP must discharge to a downstream conveyance system. Trash and sediment accumulate within the forebay as stormwater passes into the basin. Infiltration basins are highly effective in removing all targeted Figure 1 – Infiltration Basin pollutants from stormwater runoff. See Appendix A, and Appendix C, Section 1 of Basin Guidelines, for additional requirements. Siting Considerations The use of infiltration basins may be restricted by concerns over ground water contamination, soil permeability, and clogging at the site. See the applicable WQMP for any specific feasibility considerations for using infiltration BMPs. Where this BMP is being used, the soil beneath the basin must be thoroughly evaluated in a geotechnical report since the underlying soils are critical to the basin’s long term performance. To protect the basin from erosion, the sides and bottom of the basin must be vegetated, preferably with native or low water use plant species. In addition, these basins may not be appropriate for the following site conditions: Industrial sites or locations where spills of toxic materials may occur Sites with very low soil infiltration rates Sites with high groundwater tables or excessively high soil infiltration rates, where pollutants can affect ground water quality Sites with unstabilized soil or construction activity upstream On steeply sloping terrain Infiltration basins located in a fill condition should refer to Appendix A of this Handbook for details on special requirements/restrictions Riverside County - Low Impact Development BMP Design Handbook rev. -

Examples of Stormwater Control Devices

Stormwater Control Devices Filtration Basin A SHALLOW BASIN WITH ENGINEERED OR AMENDED SOIL AND AN UNDERDRAIN SYSTEM Filtration basins function by detaining stormwater in the basin. As stormwater infiltrates through the amended soil, sand, or engineered media, pollutants are filtered and adsorbed onto soil particles. Treated stormwater is directed to the receiving stream via the underdrain system. Filtration basins may be shaped like ponds or channels. To improve pollutant removal, the basin may be covered with grass, wetland species, or landscaped vegetation (see Bioretention Basin). Sand filters are considered filtration basins. Filtration basins may have outlet control structures and emergency spillways. However, all filtration basins have underdrain systems. Bioretention Basin A TYPE OF FILTRATION BASIN WITH ENGINEERED MEDIA , AN UNDERDRAIN SYSTEM , AND LANDSCAPED VEGETATION Bioretention basins use a landscaped mix of water- tolerant plants to improve pollutant removal. The vegetation is selected for its ability to physically filter and uptake stormwater pollutants. As with all filtration basins, stormwater is infiltrated through amended soil or an engineered media before it enters the underdrain system. Selected vegetation simulates various ecosystems such as forests, meadows, and hedgerows Bioretention basins are suited to drainage areas less than 1 acre. Bioretention basins may include outlet control structures and emergency spillways, but they will always have underdrain systems. Dry Detention Basin A SHALLOW , DRY BASIN WITH AN OUTLET PIPE OR ORIFICE AT THE INVERT OF THE BASIN Dry detention basins attenuate peak discharges and temporarily detain runoff to promote sedimentation of solids and infiltration. Runoff is slowly released from an outlet control structure at a steady flow rate to increase detention time. -

Storm Water Permitting Requirements for Construction Activities

Storm Water Permitting Requirements for Construction Activities John Mathews Storm Water Program Manager Division of Surface Water Why Permit Storm Water? Impacts During Construction • Not an issue until we add rainfall… Impacts During Construction Impacts During Construction • Large amounts of sediment are transported downstream and embed streams. Impacts During Construction • A healthy versus an embedded stream bottom. Post-Construction Impacts • Efficient runoff and pollution delivery Post-Construction Impacts • Stream Erosion (erosion and downcutting) Post-Construction Impacts • Stream Erosion (erosion and downcutting) History of the Construction General Permit (CGP) Increased Sediment Storage; Required Basic Erosion and Skimmers on Sediment Control, Sediment Basins; Very General Post- Allowed Offsite Major Update of Post- Construction, ≥5 Mitigation of Post- Construction acres of disturbance Construction Requirements 1992 2003 2008 2013 2018 ≥ 1 acre; Added Minor Changes Specific Post- construction, Large ≥ 5 and Small (1-5 ac) Sites Authorizes Storm Water Discharge From • Construction activities - clearing, grading, excavating, grubbing and/or filling – that disturb ≥ 1 acres – or will disturb < 1 acre of land but are part of a larger common plan of development or sale that will ultimately disturb ≥ 1 acres • Associated support activities (on-site or contiguous batch plants, borrow pits, & material storage areas) A Statewide Permit • But two watersheds have special conditions (the Big Darby and portions of the Olentangy) • Submittal -

Stormwater Management Dry Wells and Infiltration Basins

WENTWORTH WATERSHED RESTORATION AND PROTECTION STRATEGIES 1 Stormwater Management Dry Wells and Infiltration Basins DRY WELL A dry well is essentially small subsurface leaching basins. It consists of a small pit filled with stone, or a small structure surrounded by stone, used to temporarily store and infiltrate runoff from a very limited contributing area. Dry wells are well-suited to receive roof runoff via building gutter and downspout systems. Runoff enters the structure through an inflow pipe, inlet grate, or through surface infiltration. The runoff is stored in the structure and/or void spaces in the stone fill. Properly sited and designed dry wells provide treatment of runoff as pollutants become bound to the soils under and adjacent to the well, as the water percolates into the ground. The infiltrated stormwater contributes to recharge of the groundwater table. A commercially manufactured drywell being installed to capture water from roof downspout. Stormwater Runoff Dry Wells and Infiltration Basins (continued) 2 INFILTRATION BASINS Infiltration basins are structures designed to temporarily store runoff, allowing all or a portion of the water to infiltrate into the ground. The structure is designed to completely drain between storm events. In a properly sited and designed infiltration basin, water quality treatment is provided by runoff pollutants binding to soil particles beneath the basin as water percolates into the subsurface. Biological and chemical processes occurring in the soil also contribute to the breakdown of pollutants. Infiltrated water is recharged to the underlying groundwater. Subsurface infiltration basins may comprise a subsurface manifold system with associated crushed stone storage bed, or specially-designed chambers (with or without perforations) bedded in or above crushed stone. -

Chapter 6 - Infiltration Bmps

Chapter 6 - Infiltration BMPs Infiltration measures control stormwater quantity and quality by retaining runoff on-site and discharging it into the ground through absorption, straining, microbial decomposition and trapping of particulate matter. Infiltration systems should not be used if the intercepted runoff is anticipated to contain pollutants that can affect groundwater quality, such as hydrocarbons, nitrate, and chloride. When the subsoils are appropriate, an infiltration basin can be suitable for treating and controlling the runoff from very small to very large drainage areas. However, some commercial or industrial sites may have contaminants that may not be treatable by soil filtration and should be avoided. Figure 6-1 shows a typical infiltration basin. IMPORTANT: This chapter describes three common Infiltration BMPs: infiltration basins, dry wells, and infiltration trenches. In addition to these infiltration techniques, there are several Low Impact Design (LID) techniques that rely on infiltration in small systems dispersed throughout a site, rather than an end- of-pipe technique such as the infiltration basin. Sizing: Infiltration systems must be designed to retain a runoff volume equal to 1.0 inch times the subcatchment's impervious area plus 0.4 inch times the subcatchment's landscaped developed area and infiltrate this volume into the ground. The infiltration system must drain completely within 24 to 48 hours following the runoff event. Complete drainage is necessary to maintain aerobic conditions in the underlying soil to favor bacteria that aid in pollutant attenuation and to allow the system to recover its storage capacity before the next storm event. Site Suitability: The following are some recommendations on the suitability of a site: Soil Permeability: The permeability of the soil at the depth of the base of the proposed infiltration system should be no less than 0.50 inches per hour and no greater than 2.41 inches per hour. -

Los Angeles River Watershed

UCLA Recent Work Title LA Sustainable Water Project: Los Angeles River Watershed Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/42m433ps Authors Mika, Katie Gallo, Elizabeth Read, Laura et al. Publication Date 2017-09-19 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ 4.0 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California LA SUSTAINABLE WATER PROJECT: LOS ANGELES RIVER WATERSHED This report is a product of the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, UCLA Sus- tainable LA Grand Challenge, and Colorado School of Mines. AUTHORS Katie Mika, Elizabeth Gallo, Laura Read, Ryan September 2017 Edgley, Kim Truong, Terri Hogue, Stephanie Pincetl, Mark Gold ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS UCLA Grand Challenges, Sustainable LA This research was supported by the City of Los 2248 Murphy Hall Angeles Bureau of Sanitation (LASAN). Many Los Angeles, CA 90005-1405 thanks to LASAN for providing ideas and direc- tion, facilitating meetings and data requests, as well as sharing the many previous and current re- UCLA Institute of the Environment and search efforts that provided us with invaluable in- Sustainability formation on which to build. Further, LASAN La Kretz Hall, Suite 300 and LADWP provided data and edits that helped Box 951496 to deepen and improve this report. Any findings, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1496 opinions, or conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of LASAN. Colorado School of Mines 1500 Illinois Street Golden, CO 80401 We would like to acknowledge the many organiza- tions which facilitated this research through providing data, conversations, reviews, and in- sights into the integrated water management world in the Los Angeles region: LADWP, LAC- DPW, LARWQCB, LACFCD, WRD, WBMWD, MWD, SCCWRP, the Mayor’s Office of Sustaina- bility, and many others. -

Green Infrastructure To

1 2 3 USING GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE TO 4 MANAGE URBAN STORMWATER QUALITY: 5 A Review of Selected Practices and State Programs 6 7 8 A DRAFT REPORT TO 9 THE ILLINOIS ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY 10 11 by: 12 13 Martin Jaffe, Moira Zellner, Emily Minor, 14 Miquel Gonzalez-Meler, Lisa Cotner, and Dean Massey, 15 University of Illinois at Chicago 16 17 Hala Ahmed and Megan Elberts, 18 Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning 19 20 Hal Sprague and Steve Wise 21 Center for Neighborhood Technology 22 23 Brian Miller 24 Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant College Program 25 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 26 27 June 24, 2010 28 29 30 31 32 This research report was funded by the 33 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 34 35 36 1 1 2 2 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 4 ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………..…………..5 5 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY………………………………………………….….....…..7 7 8 CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION…..…..………………….………………….…......21 9 10 CHAPTER II: THE EFFECTIVENESS OF GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE…..27 11 Indicators of Effectiveness…………………………………………….………..28 12 Sources of Data for Assessing Green Infrastructure Effectiveness…….……….29 13 Green Infrastructure Performance…………….……………………………........31 14 The International Stormwater BMP Database………………………………......34 15 Sources of Variation……………………………………………………….…….36 16 Maintenance and Effectiveness………………………………………….….…...38 17 Conclusions……………………………………………………………….……...39 18 19 CHAPTER III: FUNDING GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE…………...…………..41 20 The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act………………………….……...41 21 The Cost-Effectiveness -

PC-28 INFILTRATION BASIN Definition and Purpose An

Best Management Practices Manual PC-28 Infiltration Basin PC-28 INFILTRATION BASIN Reference: Maryland Stormwater Design Manual. BMP Objectives Perimeter Control Slope Protection Borrow and Stockpiles Drainage Areas Sediment Trapping Stream Protection Temporary Stabilizing Permanent Stabilizing Definition and Purpose An infiltration basin is used to capture and treat a volume of stormwater runoff. This BMP consists of an excavated basin (sometimes rock-filled) in which runoff is collected and percolated to the surrounding soils. Grass channels, filter strips, or forebays can be used to reduce sediments entering the basin. The basin has a flat floor with an underdrain system and an outfall to drain higher volumes of flow. Appropriate Applications Can be used to enhance stormwater quality, reduce peak discharges, and recharge groundwater. Should not be used on or adjacent to steep slopes and should not be used within fill soils. Can be used to pre-treat portions of the water quality volume if used as an upstream stilling basin. Typically used for drainage areas less than 5 acres. Should only be used with well-drained soils of Hydrologic Soil Groups A or B. Should not be installed in highly permeable sand or gravel seams that are directly connected to aquifers. Can be directly connected to parking lot drains, roof downspouts, or other inlet structures. Design Parameters The bottom of the basin should be 4 feet higher than the seasonal high water table or bedrock. Generally, basins are designed to infiltrate retained runoff within a 48-hour period. 08/11 Chapter 5 Post-Construction Best Management Practices Manual PC-28 Infiltration Basin A dense vegetative cover needs to be established over all contributing pervious areas before runoff can be conveyed to the basin. -

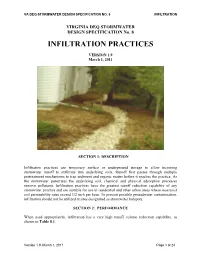

Infiltration Practices

VA DEQ STORMWATER DESIGN SPECIFICATION NO. 8 INFILTRATION VIRGINIA DEQ STORMWATER DESIGN SPECIFICATION No. 8 INFILTRATION PRACTICES VERSION 1.9 March 1, 2011 SECTION 1: DESCRIPTION Infiltration practices use temporary surface or underground storage to allow incoming stormwater runoff to exfiltrate into underlying soils. Runoff first passes through multiple pretreatment mechanisms to trap sediment and organic matter before it reaches the practice. As the stormwater penetrates the underlying soil, chemical and physical adsorption processes remove pollutants. Infiltration practices have the greatest runoff reduction capability of any stormwater practice and are suitable for use in residential and other urban areas where measured soil permeability rates exceed 1/2 inch per hour. To prevent possible groundwater contamination, infiltration should not be utilized at sites designated as stormwater hotspots. SECTION 2: PERFORMANCE When used appropriately, infiltration has a very high runoff volume reduction capability, as shown in Table 8.1. Version 1.9, March 1, 2011 Page 1 of 24 VA DEQ STORMWATER DESIGN SPECIFICATION NO. 8 INFILTRATION Table 8.1. Summary of Stormwater Functions Provided by Infiltration Stormwater Function Level 1 Design Level 2 Design Annual Runoff Volume Reduction 50% 90% (RR) Total Phosphorus (TP) EMC Reduction1 by BMP Treatment 25% 25% Process Total Phosphorus (TP) Mass 63% 93% Load Removal Total Nitrogen (TN) EMC Reduction1 by BMP Treatment 15% 15% Process Total Nitrogen (TN) Mass Load 57% 92% Removal Channel and Flood Protection Use the RRM spreadsheet to calculate the Curve Number (CN) adjustment; OR Design for extra storage (optional; as needed) on the surface or in the subsurface storage volume to accommodate larger storm volumes, and use NRCS TR-55 Runoff Equations 2 to compute the CN Adjustment. -

INFILTRATION BASINS Guidelines for Maintenance

INFILTRATION BASINS Guidelines for Maintenance n infiltration basin is a storm water best management practice (BMP) designed to capture Arunoff and let it soak into the ground—a process called infiltration. The basin is carefully engineered to infiltrate runoff volumes from the specific land area, or watershed that drains to the basin. Runoff will enter the infiltration basin through a combination of underground pipes, ditches and overland flow. A small pond, or forebay, is usually constructed at the inflow area to trap sediment and attached pollutants before entering the infiltration basin. This can help prevent plugging the soils in the infiltration basin. The bottom of the infiltration basin is flat, wide and planted with vegetation specifically designed to encourage infiltration (see page 2). There may be a stone-filled trench constructed within the basin bottom or near the perimeter to further enhance infiltration, especially during frozen ground periods. The basin will usually have an overflow pipe and an emergency spillway to handle runoff events that exceed the design capacity. The infiltration basin is generally designed not to pond runoff in the basin for more than a few days at a time. An infiltration basin may act like a leaky pond, but they are very effective at protecting local lakes, rivers and downstream properties from water pollution and flooding caused by urban runoff. Infiltrating runoff also helps replenish the groundwater, the source of drinking water for 80% of Wisconsin residents. Groundwater also supports water levels in local lakes and base flows in streams, especially during periods of dry weather. Note: Rain gardens are essentially small infiltration basins. -

Presented Below Are Water Quality Standards That Are in Effect for Clean Water Act Purposes

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. I Stormwater Management Volume Two: Stormwater Technical Handbook March 1997 Prepared by: MA Department of Environmental Protection C2:M MA Office of Coastal Zone Management Stormwater Management Volume Two: Stormwater Technical Handbook March 1997 Funding for this document was provided by: · Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, · Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management, and · U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The document also was partially funded by a grant from the Office of Ocean and ) ' Coastal Resources Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric - Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOAA or any of its subagencies. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts William F. Weld, Governor Argeo Paul Cellucci, Lieutenant Governor Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Tmdy Coxe, Secretary Department of Environmental Protection David B. Struhs, Commissioner Bureau of Resource Protection Arleen O' Donnell, Assistant Commissioner This information is available in alternate formats upon request. ) Prinled on recycled paper .' Table of Contents