Refections on Fascism and Communism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

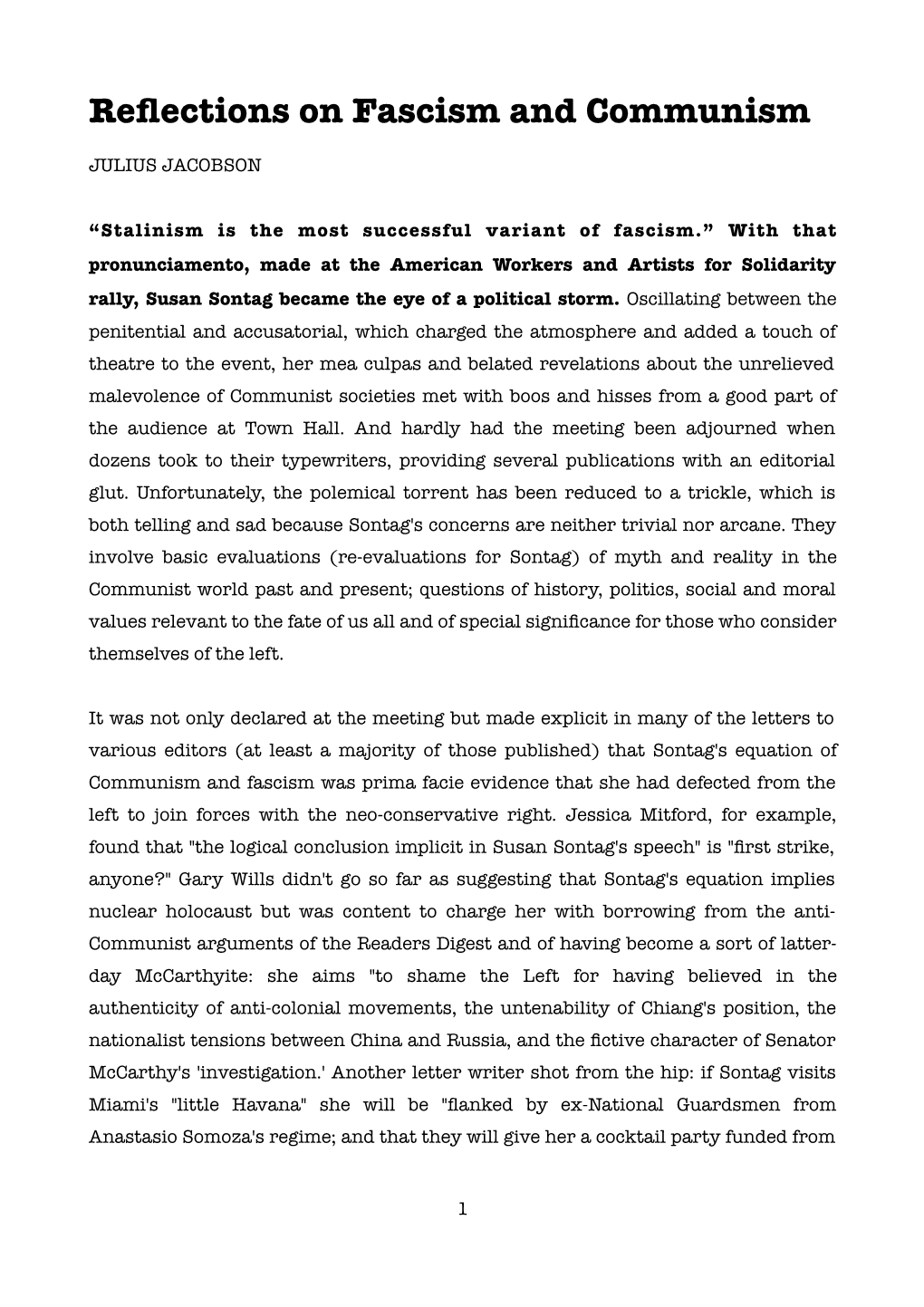

In Tribute to Phyllis Jacobson

In Tribute to Phyllis Jacobson JULIE AND PHYLLIS JACOBSON LAUNCHED New Politics in the early 1960s, when they saw the absence of a voice for authentic left-socialist thought following the demise of the Independent Socialist current of the previous period. Ironically, although it was a time of reborn activism for civil rights, peace and what we now call “global justice,” the movement for a socialist politics fiercely independent of Washington, Moscow and Beijing had not organizationally survived to see it. New Politics, along with those activists who a few years later initiated the Independent Socialist Clubs, were instrumental in giving the movement a new beginning. New Politics brought to the international left’s attention the Polish Marxists Kuron and Modzelewski’s “Open Letter to the Party,” among other seminal texts including Hal Draper’s “The Two Souls of Socialism” and “Origins of the Middle East Crisis.” Julie and Phyllis were a remarkable team, but by all accounts Phyllis in particular was the guts and glue of the magazine’s production, circulation and financial management. And so it was again when they relaunched the journal after an eight-year lapse in the 1980s to address the new movements of that day, and through the tumultuous decade and more following the fall of the Berlin Wall, the demise of the Soviet Union and the end of the monstrous bureaucratic tyranny that went under that grotesque label, “actually existing socialism.” It’s an interesting concidence that the years of Phyllis’s life, 1922-2010, match those of Howard Zinn. Zinn of course is justifiably famous, but fewer people really understand the contributions of Phyllis and those like her who are the stalwarts and geniuses of organization. -

The Student Uprising That Ushered in the Radical Sixties: the Berkeley Free Speech Movement

The Student Uprising That Ushered In the Radical Sixties: The Berkeley Free Speech Movement Book Review: Hal Draper, Berkeley, The New Student Revolt. Haymarket, 2020. Thomas Harrison The current mass upheaval has reached a scale not seen in this country since the 1960s. So it is timely that Haymarket Books has republished an account of one of the key revolts in that fabled decade – the 1964 Free Speech Movement (FSM) at the University of California at Berkeley. Originally issued by Grove Press in 1965 and published in a second edition in 2010 by the Center for Socialist History, Hal Draper’s book remains the most vivid narrative and incisive analysis of the FSM that I know. A Marxist scholar of immense learning and a veteran of the revolutionary socialist movement, he was also a deeply involved participant in the FSM itself. Indeed, Draper’s influence led UC President Clark Kerr to call him, hyperbolically, “the chief guru of the FSM.” Berkeley, The New Student Revolt recommends itself to all those interested in the history of protest and the left in this country, but especially, I think, to the young radicals and socialists who are today immersed in the great multiracial movement against racism and police violence and for fundamental social change. Draper became a Trotskyist in the 30s. He was part of the tendency led by Max Shachtman that split from the Trotskyists in 1940 in a dispute over the nature of the Soviet Union and formed the Workers Party. The group, which changed its name to the Independent Socialist League (ISL) in 1949, stood for what it called the Third Camp, in opposition to both capitalism and the “bureaucratic collectivism” of the Soviet Bloc and Communist China. -

Churchills Rebels: Esmond Romilly and Jessica Mitford Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CHURCHILLS REBELS: ESMOND ROMILLY AND JESSICA MITFORD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Meredith Whitford | 256 pages | 05 Jun 2014 | Umbria Press | 9781910074015 | English | London, United Kingdom Churchills Rebels: Esmond Romilly and Jessica Mitford PDF Book At the age of eighteen he joined the International Brigades and fought on the Madrid front during the Spanish Civil War , of which he wrote and published a vivid account. Romilly had been assiduous in developing a distribution network "in every cloister and dormitory he could reach", [37] and had acquired a wide selection of contributions, so that the magazine ran to 35 pages. Carter Jr. They moved to London and lived in the East End , then mostly a poor industrial area. Books by Meredith Whitford. Hozier appeared to have accepted that the elder daughters were probably his, but largely ignored the twins who, when the marriage ended in , remained with their mother while Hozier initially took responsibility for the older girls before disappearing from the family scene altogether. Paperback , pages. Showing The families, bitterly opposed to the union, hoped to avoid press attention, but Romilly opportunistically exploited press interest by selling his story through an intermediary. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. The baby died in a measles epidemic the following May. The Observer. Kira Gillett marked it as to-read May 15, Thomas Milner Gibson. She recorded two short albums: one [18] contains her rendition of " Maxwell's Silver Hammer " and " Grace Darling ", [19] and the other, two duets with friend and poet Maya Angelou. She performed at numerous benefits and opened for Cyndi Lauper on the roof of the Virgin Records store in San Francisco. -

Jessica Mitford Part 4 of 8

?92 .,- . - _ -- _..,._. _....r_.T___- 1- .. _'¢__. _ _.,.;_ _. ..; _,,,_.L.__ . _r__ V .7 7 - _;__,.... _. _ .,_____ __ V 'U Y ____ __ = . _. s- . '§..=.1_.-713'.-;IIflI t =~,::.-1-i=..* I , - _ -t /' '92; :. -- en " . E: 17-I. Rev.8-1 1-03! we ATTENTION 5' -a W .4 The following documents appearing in FBI les have been reviewed under the provisions of The Freedom of 2: Information Act FOIA! Title 5, United States Code, Section 552!; Privacy Act of 1974 PA! Title 5, United States Code, Section 552a!; and/or Litigation. 5'? " IQ s 1 . @911E] FOIAIPA U Litigation El Executive Order Applied vii 15-: Requester: ' _ q E I -1: Subject: __ _ __ Computer or Case Identication Number: Title of Case: _ _ _ Section ___________ Ii * File __ __ __ _ ,_ 7" _ _ _ Serials Reviewed: 17 E5-:1 ; '= b7C1 e if ., m I; '¬92_ ei; "5 Release Location: *File _ _ Section t':= I?-it_,I! F . .:?§§..--n....,.c. 1; _ . _ __ _ n ___ __ W4. ._.._.. mm. .~/ . ;__ **_ 77* V ' '.?' This le section has been scanned into the FOIPA Document Processing System FDPS!prior to National Security Classication review. Please see the documents locat ' current classication action, if warranted. Direct ! -,.et 4 . inquires about the FDPS to RIDS Service Request Unit .33 ii W 5:51 File Number: W f . A Section '2 5,-*2 Scrial s!Reviewed: ' __ _ _ ___ __ _ _ _7 __ __ ____ " -2; FOIPA Requester: _. -

Bio-Bibliographical Sketch of Max Shachtman

The Lubitz' TrotskyanaNet Max Shachtman Bio-Bibliographical Sketch Contents: • Basic biographical data • Biographical sketch • Selective bibliography • Notes on archives Basic biographical data Name: Max Shachtman Other names (by-names, pseud. etc.): Cousin John * Marty Dworkin * M.S. * Max Marsh * Max * Michaels * Pedro * S. * Max Schachtman * Sh * Maks Shakhtman * S-n * Tr * Trent * M.N. Trent Date and place of birth: September 10, 1904, Warsaw (Russia [Poland]) Date and place of death: November 4, 1972, Floral Park, NY (USA) Nationality: Russian, American Occupations, careers, etc.: Editor, writer, party leader Time of activity in Trotskyist movement: 1928 - ca. 1948 Biographical sketch Max Shachtman was a renowned writer, editor, polemicist and agitator who, together with James P. Cannon and Martin Abern, in 1928/29 founded the Trotskyist movement in the United States and for some 12 years func tioned as one of its main leaders and chief theoreticians. He was a close collaborator of Leon Trotsky and translated some of his major works. Nicknamed Trotsky's commissar for foreign affairs, he held key positions in the leading bodies of Trotsky's international movement before, in 1940, he split from the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), founded the Workers Party (WP) and in 1948 definitively dissociated from the Fourth International. Shachtman's name was closely webbed with the theory of bureaucratic collectivism and with what was described as Third Campism ('Neither Washington nor Moscow'). His thought had some lasting influence on a consider able number of contemporaneous intellectuals, writers, and socialist youth, both American and abroad. Once a key figure in the history and struggles of the American and international Trotskyist movement, Shachtman, from the late 1940s to his death in 1972, made a remarkable journey from the left margin of American society to the right, thus having been an inspirer of both Anti-Stalinist Marxists and of neo-conservative hard-liners. -

SPEC.RAR.CMS.89 Jessica Mitford Audio-Visual Materials VHS/U-Matic Transferred to DVD

SPEC.RAR.CMS.89 Jessica Mitford Audio-Visual Materials VHS/U-Matic transferred to DVD Boxes 282 - 287 Box 282 89-1. J.M. “First Interview, general” RT 00:21:17 • Quality – good • Content- Interview; politics, writing, general 89-2. J.M. “First Interview, general” RT 00:21:08 • Quality – good • Content- Interview cont.; family, growing up, her children, education, running away with Esmond, convent, fascism 89-3. J.M. “First Interview, general” RT 00:21:36 • Quality – good • Content- interview cont.; politics, Central America, journalism, communist party, humor in writing • Audio cuts out around 16:00 for 10 seconds 89-4. “JM – second interview, the early years” (Tape 1) RT 00:20:48 • Visual quality fair – a little fuzzy • Audio quality good • Content includes Philip Toynbee, writing in regards to Faces of Philip, Central America, Esmond Romilly, running away to Spain 89-5. “Decca Interview” (Tape 2) RT 00:21:36 • Visual quality fair – somewhat fuzzy • Audio quality good • Content includes running away account, Spain, Esmond, family, politics, moving to the United States 89-6. “Interview with Decca – Unity” (Tape 3) RT 00:22:17 • Audio quality good; visual quality fair – a little fuzzy/ somewhat low light • Content includes first arriving in the U.S., press attention, Unity, Dianna, Unity’s attempted suicide, AWOD 89-7. “Interview with Decca; older title – Cof San Diego #2” RT 00:14:36 • Quality- poor • ~ 00:46 end of interview, shows Mitford talking on phone, then you hear dialogue between Mitford and interviewer about how the interview went while seeing Mitford walk around the house, then Mitford on phone again • Audio cuts out ~ 03:20 • Camera jumps around, unfocused • Visual cuts out ~ 3:30 • Static and then film that was taped over- no audio, very poor visual, quality worsens as it reaches end of tape 89-8. -

Vita for Alan M. Wald

1 July 2016 VITA FOR ALAN M. WALD Emeritus Faculty as of June 2014 FORMERLY H. CHANDLER DAVIS COLLEGIATE PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AND AMERICAN CULTURE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, ANN ARBOR Address Office: Prof. Alan Wald, English Department, University of Michigan, 3187 Angell Hall, Ann Arbor, Mi. 48109-1003. Home: 3633 Bradford Square Drive, Ann Arbor, Mi. 48103 Faxes can be received at 734-763-3128. E-mail: [email protected] Education B.A. Antioch College, 1969 (Literature) M.A. University of California at Berkeley, 1971 (English) Ph. D. University of California at Berkeley, 1974 (English) Occupational History Lecturer in English, San Jose State University, Fall 1974 Associate in English, University of California at Berkeley, Spring 1975 Assistant Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1975-81 Associate Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1981-86 Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1986- Director, Program in American Culture, University of Michigan, 2000-2003 H. Chandler Davis Collegiate Professor, University of Michigan, 2007-2014 Professor Emeritus, University of Michigan, 2014- Research and Teaching Specialties 20th Century United States Literature Realism, Naturalism, Modernism in Mid-20th Century U.S. Literature Literary Radicalism in the United States Marxism and U.S. Cultural Studies African American Writers on the Left Modernist Poetry and the Left The Thirties New York Jewish Writers and Intellectuals Twentieth Century History of Socialist, Communist, Trotskyist and New Left Movements in the U.S. -

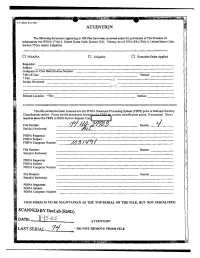

For Phyllis Jacobson, a Comrade

For Phyllis Jacobson, A Comrade THOSE OF US WHO KNEW Phyllis Jacobson and her husband Julie will realize that her death brings to a close a long and rich chapter in the history of the revolutionary and democratic socialist left in the US. She was the last of a small but heroic generation. Starting with the YPSL Fourth International, the youth section of the Socialist Party that split under Trotskyist leadership to set up the Socialist Workers Party in 1938 she and Julie ended up in the Workers Party (later the Independent Socialist League) when it was formed in 1940. She and most WPers, followers of a then still revolutionary socialist Max Shachtman, spent the years of the Second World War working "in industry," trying to radicalize the fast growing Labor movement. After the war Julie and she founded the anti-war Third Camp socialist journal ANVIL, which was directed at students and which had a circulation in many thousands . I remember we sold more than 1,000 at City College alone in 1951, and it was a big item on the slowly growing student left in Berkeley, Chicago, Brooklyn and other centers of student activism against the Korean war. It was at ANVIL editorial board meetings in their Greenwich Village apartment that we first met. The Jacobsons remained active when the ISL and ANVIL ended up in the Socialist Party in 1957. In the Party she (and I) remained "hard left" third camp anti-war socialists. When the Party split in 1970 and DSOC (later DSA) were founded we lost regular personal touch, but we remained in contact through New Politics, which was and remained the premier Third Camp, anti-Stalinist independent socialist journal in the US, perhaps the English-speaking world. -

The Workers' Party Revisited by Betty Reid Mandell Associate Professor of Social Work

Bridgewater Review Volume 3 | Issue 2 Article 12 Jul-1985 Cultural Commentary: The orW kers' Party Revisited Betty Reid Mandell Bridgewater State College Recommended Citation Mandell, Betty Reid (1985). Cultural Commentary: The orkW ers' Party Revisited. Bridgewater Review, 3(2), 23-25. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol3/iss2/12 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. CULTURAL COMMENTARY The Workers' Party Revisited by Betty Reid Mandell Associate Professor of Social Work your houses." In 1948 this small group of ers' Party, another on Harvey Swados' 1970 Though conservative politicians tend to radicals, called the Worker's Party, was novel Standing Fast as a portrayal of the portray socialism as a unified, monolithic placed on Attorney General Tom Clark's list Workers' Party, and the third on three force, its history as an American political of subversive organizations. In 1958 they journals which had their roots in the Work and ideological movement is, as Betty Man were removed from the list. Then they ers' Party: Politics, Dissent, and New Po dell reports. anything but unified. To under disbanded. litics. Invitations were sent to former Work standsomething ofthe issues with which the Twenty-six years later, on May 6-7, 1983, ers' Party activists, some friends, and some movement has struggled, a bit of back some of that small group and a few friends contributors to early issues of the journals. ground may be useful. reassembled at New York University'S Tam The invitation list was a story in itself, In 1929 the Communist League ofAmer iment Library for a Workers' Party/ Stand combining those who had stood fast in their ica (later to change its name to the Socialist ing Fast conference to reminisce about old radicalism and those who had turned to the Workers Party - SWP) was founded on times and to celebrate the acquisition by right. -

The Outsiders: Jessica Mitford John Pilger, Alan Lowery

— THE OUTSIDERS: JESSICA MITFORD JOHN PILGER, ALAN LOWERY THE POWER OF THE DOCUMENTARY: BREAKING THE SILENCE thepowerofthedocumentary.com.au A FILM FESTIVAL CURATED BY JOHN PILGER The Outsiders: Jessica Mitford — Presenter: Sound: Jessica Mitford, the ‘red sheep’ of the Treuhaft persuaded her to write an Jessica Mitford died in 1996 at the John Pilger Bob Withey aristocratic Mitford family, left behind article about the corrupt funeral age of 78, having not long completed Director: Film editor: her own charmed background and never business. Called ‘Saint Peter Don't You her final book, The American Way of Alan Lowery Jonathan Morris allowed this privilege to prevent her Call Me’, it appeared in Frontier magazine Death Revisited, which disclosed a Production company: Recommended rating: campaigning for the rights of others – and lifted the lid on the many scandals host of new funeral directors’ scams. Tempest Films PG making her a perfect fit for John Pilger’s of profiteering that plagued the bereaved On her instructions, she was cremated Producer: Colour, 26 mins 1983 interview series The Outsiders. in the United States. without a ceremony and her ashes were Jacky Stoller UK, 1983 scattered at sea. ‘Jessica Mitford,’ said Researcher: Known as ‘Decca’, she was the sister of This became a bestselling book, Pilger, ‘combined a finely honed social Mike Coren romantic novelist Nancy, Diana, the wife The American Way of Death, whose conscience and a wonderful gallows Camera: of fascist Oswald Mosley, and Unity, who revelations of unscrupulous practices humour. She inverted stereotypes. Rik Stratton was obsessed with Hitler. In 1937, she by undertakers led to Congressional I liked her enormously.’ ran away to Spain with Esmond Romilly, hearings. -

Jessica Mitford Part 2 of 8

i . i . 7% M7 -r 5 _ .. ~..v.¢~_ l7-l Rev. 2-11-03! O O" " C ATTENTION E The following documents appearingin FBI les have been reviewedunder the provisions of The Freedomof Infomlation Act FOIA! Title 5, UnitedStates Code,Section 552!;Privacy Actof I974 PA! Title 5, UnitedStates Code, Section 5522!;and/or Litigation. C El FOIAIPA El Litigation El Executive Order Applied Requester: _7_ ___ __ ____ ,__ Subject: _ Computeror Case Identication Number: C E ...._ _ Title of Case; _ __ p__ _ __ _ ' Section i * File ___ C A _ __ Serials Reviewed: C i_ ii _ ' ~ L be e e t ~ ~b7l E _ Release Location:*Fi1e _ , ____ Section t _ i l , fr _:="' . t S st,_ ix _ ' . --'7"*_, . '*| This le section hasbeen scannedinto theFOIPA DocumentProcessing System FDPS! priorto National Security t Classication review. Please seethe documentslocat ' -= current classication action, if warranted. Direct inquires about the FDPS to RIDS ServiceRequest Uni File Number: M _ _ SectionC%C } Se:-ial s!Reviewed: ' t FOIPA Requester: __: C CC t If FOIPA Subject; _ ' pC FOIPAComputer Number: /C J92t FileSerial Number: s!Reviewed: l "WC _CC_ _ _ ,_ _ C C C ' Section_C FOIPA Requester: ______ __ _____:_ _ __ __ CC __ _ FOIPA Subject: C Q t 92 FOIPA ComputerNumber: _ __ __ CC C_ C _T C__ FileNumber: _p ._ __ _p ___7 7 __ ___ Sectionj___i__ Seria1 s! Reviewed: i ;_n ___ _ _ 1 FOIPARequester:CC C CC. -

Rethinking the Historiography of United States Communism

American Communist History, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2003 Rethinking the Historiography of United States Communism BRYAN D. PALMER Questioning American Radicalism We ask questions of radicalism in the United States. Many are driven by high expectations and preconceived notions of what such radicalism should look like. Our queries reflect this: Why is there no socialism in America? Why are workers in the world’s most advanced capitalist nation not “class conscious”? Why has no “third party” of laboring people emerged to challenge the estab- lished political formations of money, privilege, and business power? Such interrogation is by no means altogether wrongheaded, although some would prefer to jettison it entirely. Yet these and other related questions continue to exercise considerable interest, and periodically spark debate and efforts to reformulate and redefine analytic agendas for the study of American labor radicals, their diversity, ideas, and practical activities.1 Socialism, syndicalism, anarchism, and communism have been minority traditions in US life, just as they often are in other national cultures and political economies. The revol- utionary left is, and always has been, a vanguard of minorities. But minorities often make history, if seldom in ways that prove to be exactly as they pleased. Life in a minority is not, however, an isolated, or inevitably an isolating, experience. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the US gave rise to a significant left, rooted in what many felt was a transition from the Old World to a New Order. Populists,