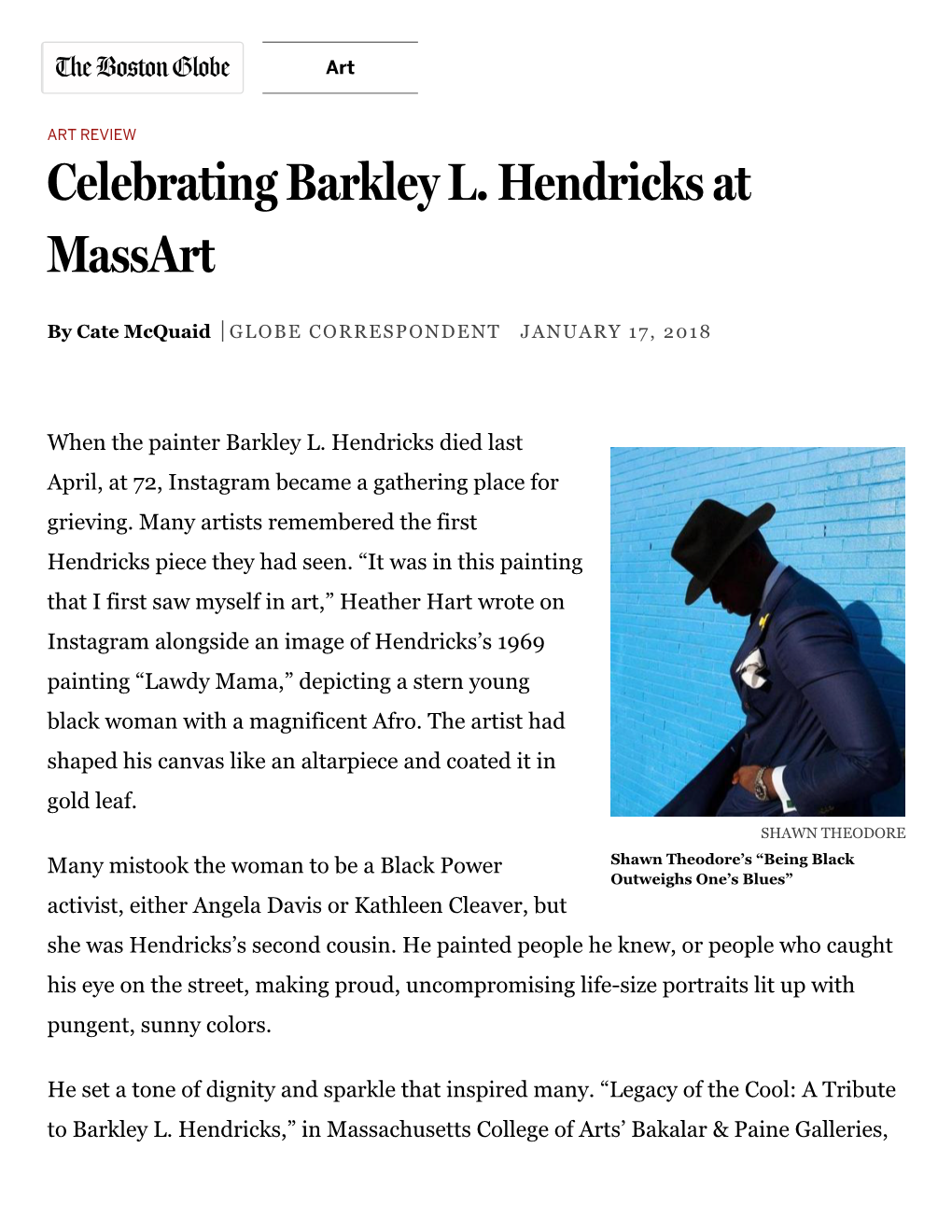

Celebrating Barkley L. Hendricks at Massart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art in America the EPIC BANAL

Art in America THE EPIC BANAL BY: Amy Sherald, Tyler Mitchell May 7, 2021 10:08am Tyler Mitchell: Untitled (Blue Laundry Line), 2019. Amy Sherald (https://www.artnews.com/t/amy-sherald/): A Midsummer Afternoon Dream, 2020, oil on canvas, 106 by 101 inches. Tyler Mitchell and Amy Sherald—two Atlanta-born, New York–based artists—both capture everyday joy in their images of Black Americans. Recurring motifs in Mitchell’s photographs, installations, and videos include outdoor space and fashionable friends. Sherald, a painter, shares similar motifs: her colorful paintings with pastel palettes show Black people enjoying American moments, their skin painted in grayscale, the backgrounds and outfits flat. Both are best known for high-profile portrait commissions: in 2018 Mitchell became the first Black photographer to have a work grace the cover of Vogue. That shot of Beyoncé was followed, more recently, by a portrait of Kamala Harris for the same publication. Michelle Obama commissioned Amy Sherald to paint her portrait, and last year Vanity Fair asked Sherald to paint Breonna Taylor for a cover too. Below, the artists discuss the influence of the South on their work, and how they navigate art versus commercial projects. —Eds. Amy Sherald: Precious jewels by the sea, 2019, oil on canvas, 120 by 108 inches. TYLER MITCHELL: Amy, we spoke before about finding freedom and making your own moments of joy. I think of Precious jewels by the sea [2019]—your painting of two couples at the beach, showing the men standing with the women on their shoulders—as a moment that you constructed. -

The Obama Portraits, in Art History and Beyond Richard J

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. contents Foreword Kim Sajet vi Unveiling the Unconventional: Kehinde Wiley’s Portrait of Barack Obama Taína Caragol 1 “Radical Empathy”: Amy Sherald’s Portrait of Michelle Obama Dorothy Moss 25 The Obama Portraits, in Art History and Beyond Richard J. Powell 51 The Obama Portraits and the National Portrait Gallery as a Site of Secular Pilgrimage Kim Sajet 83 The Presentation of the Obama Portraits: A Transcript of the Unveiling Ceremony 98 Notes 129 Selected Bibliography 137 Credits 139 For general queries, contact [email protected] © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Taína Caragol Unveiling the Unconventional Kehinde Wiley’s Portrait of Barack Obama On February 12, 2018, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery unveiled the portraits of President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama. The White House and the museum had worked together to commission the paintings, and, in many ways, the lead- up to the ceremony had followed tradition. But this time something was different. The atmosphere was infused with the coolness of the there- present Obamas, and the event, which was made memorable with speeches from the sitters, the artists, and Smithsonian officials, erupted with applause at the first glimpse of these two highly unconventional portraits. Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of the president portrays a man of extraordinary presence, sitting on an ornate chair in the midst of a lush botanical setting (p. -

Valeska Soares B

National Museum of Women in the Arts Selections from the Collection Large-Print Object Labels As of 8/11/2020 1 Table of Contents Instructions…………………………………………………..3 Rotunda……………………………………………………….4 Long Gallery………………………………………………….5 Great Hall………………….……………………………..….18 Mezzanine and Kasser Board Room…………………...21 Third Floor…………………………………………………..38 2 National Museum of Women in the Arts Selections from the Collection Large-Print Object Labels The large-print guide is ordered presuming you enter the third floor from the passenger elevators and move clockwise around each gallery, unless otherwise noted. 3 Rotunda Loryn Brazier b. 1941 Portrait of Wilhelmina Cole Holladay, 2006 Oil on canvas Gift of the artist 4 Long Gallery Return to Nature Judith Vejvoda b. 1952, Boston; d. 2015, Dixon, New Mexico Garnish Island, Ireland, 2000 Toned silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Susan Fisher Sterling Top: Ruth Bernhard b. 1905, Berlin; d. 2006, San Francisco Apple Tree, 1973 Gelatin silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Gift of Sharon Keim) 5 Bottom: Ruth Orkin b. 1921, Boston; d. 1985, New York City Untitled, ca. 1950 Gelatin silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Joel Meyerowitz Mwangi Hutter Ingrid Mwangi, b. 1975, Nairobi; Robert Hutter, b. 1964, Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Germany For the Last Tree, 2012 Chromogenic print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Tony Podesta Collection Ecological concerns are a frequent theme in the work of artist duo Mwangi Hutter. Having merged names to identify as a single artist, the duo often explores unification 6 of contrasts in their work. -

Amy Sherald-Inspired Portraits

Amy Sherald-Inspired Portraits Grade: 3rd Medium: Watercolor, colored pencil & pen Learning Objective: Students will: • Observe the art of Amy Sherald. • create a portrait in her style. • Use art vocabulary. • Use good craftsmanship. Author: Juliette Ripley-Dunkelberger Elements of Art Color: the visible range of reflected light. HUE: its name; VALUE: its tints/shades; INTENSITY: its brightness/dullness. Principles of Design Emphasis (focal point): the part of an artwork that is emphasized in some way and attracts the eye and attention of the viewer; also called the center of interest. Additional Vocabulary Craftsmanship: A way of working that includes following directions, demonstrates neatness and the proper use of tools. Monochrome: having or appearing to have only one color, which may include variations on the value of that color. Portrait: works of art that record the likenesses of humans or animals. Tint: a value created by adding white to a color Wash: a painting technique that leaves a semi-transparent layer of color. A wash of diluted ink or watercolor paint applied in combination with drawing (on dry painting) is called pen and wash, wash drawing, or ink and wash. Materials & Supplies • 9”x12” watercolor paper • Salt • Large Watercolor brushes • Water cups • Cardstock – print body worksheet • Erasers • Pencils • Body templates • Drawing pens • Masking tape • 3 Skin color sets of colored pencils • Colored pencils • Pattern sheet • Paper towels • Ruler Context (History and/or Artists) Amy Sherald, (American b. Columbus, GA 1973) received degrees in painting from 2 different colleges. She was an International Artist-in-Residence in Panama. Sherald was the first woman to win the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition grand prize. -

Amy Sherald the Great American Fact

Press Release Amy Sherald The Great American Fact 20 March – 6 June 2021 Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles South Gallery Los Angeles… On 20 March, Amy Sherald, one of America’s defining contemporary portraitists, will unveil new paintings in her first West Coast solo exhibition. On view at Hauser & Wirth’s Downtown Arts District complex in Los Angeles, ‘The Great American Fact’ presents five works produced in 2020 that extend the artist’s technical innovations and distinctive visual language. Sherald is acclaimed for paintings of Black Americans at leisure that achieve the authority of landmarks in the grand tradition of social portraiture – a tradition that for too long excluded the Black men, women, and families whose lives have been inextricable from the narrative of the American experience. Subverting the genre of portraiture and challenging accepted notions of American identity, Sherald attempts to restore a broader, fuller picture of humanity. She positions her subjects as ‘symbolic tools that shift perceptions of who we are as Americans, while transforming the walls of museum galleries and the canon of art history – American art history, to be more specific.’ Sherald routinely draws upon literary references in her exhibition and the titles for her paintings. With ‘The Great American Fact’ she is referencing the 1892 book by educator Anna Julia Cooper, who wrote that Black people are ‘‘the great American fact’; the one objective reality on which scholars sharpened their wits, and at which orators and statesmen fired their eloquence.’ Sherald here employs Cooper’s statement as a framework for considering ‘public Blackness’ – the way Black American identity is shaped in the public realm. -

Best of 2018

Best of 2018: Our Top 20 Exhibitions Across the United States Art visualizing identity and community took center stage in our top 20 exhibitions across the United States for 2018. Of 72 by Ebony Patterson (detail view) (image by Sarah Rose Sharp) In 2018, artists and curators across the United States have been crafting brilliant exhibitions across the US, exploring themes of identity and community in innovative ways. Ebony G. Patterson made a maximalist tribute to victims of violence in her home country of Jamaica, while Joel Otterson crafted work recalling his parents’ professions as a seamstress and plumber. Indigenous artists took the stage at the Anchorage Museum’s Unsettled and Jeffrey Gibson’s This is the Day at the Wellin Museum. The enthralling official Obama portraits, painted by Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, were revealed at the National Gallery in DC, putting Black fine artists into the national consciousness. This list is an insight into the tastes of our US writers and the shows that moved them. 1. Gordon Parks: The New Tide, Early Work 1940– 1950 at the National Gallery of Art Gordon Parks, Washington, D.C. Government chairwoman, July 1942. Gelatin silver print mounted to board with typewritten caption sheet (image courtesy Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.) November 4, 2018–February 18, 2019 Gordon Parks taught millions of white Americans how to see Black people anew. Although he was as comfortable shooting fashion and celebrities as he was photographing the Black Panthers, his claim to greatness as a photographer rests on the Life magazine photo-essays that made him one of the mid-20th century’s foremost interpreters of African American culture and society. -

High Museum of Art Names Amy Sherald 2018 Recipient of David C

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE HIGH MUSEUM OF ART NAMES AMY SHERALD 2018 RECIPIENT OF DAVID C. DRISKELL PRIZE Sherald to be honored at 14th annual Driskell Prize Dinner on April 27 ATLANTA, Feb. 8, 2018 – The High Museum of Art today announces artist Amy Sherald as the 2018 recipient of the David C. Driskell Prize in recognition of her contributions to the field of African-American art. A Georgia native now based in Baltimore, Sherald is acclaimed for her profoundly creative and distinctive portraits of African-American subjects. In 2017, she received the commission to paint former first lady Michelle Obama’s official portrait for the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, which will be unveiled on Feb. 12, 2018. Accompanied by a $25,000 cash award, the Driskell Prize, named for the renowned African-American artist and art scholar, was founded by the High in 2005 as the first national award to celebrate an early- or mid-career scholar or artist whose work makes an original and important contribution to the field of African-American art or art history. Sherald will be honored at the 14th annual Driskell Prize Dinner at the High on Friday, April 27, at 7 p.m. Proceeds from the High’s Driskell Prize Dinner support the David C. Driskell African American Art Acquisition Funds. Since their inception, the funds have supported the acquisition of 48 works by African-American artists for the High’s “A clear unspoken granted collection. magic,” 2017, oil on canvas. “Sherald is a remarkable talent who in recent years has gained the recognition she so thoroughly deserves as a unique force in contemporary art,” said Rand Suffolk, Nancy and Holcombe T. -

Art and Architecture Catalog 2020

2020 ART AND ARCHITECTURE The Obama Portraits Taína Caragol, Dorothy Moss, Richard J. Powell & Kim Sajet From the moment of their unveiling at the National Portrait Gallery in early 2018, the portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama have become two of the most beloved artworks of our time. Kehinde Wiley’s por- trait of President Obama and Amy Sherald’s portrait of the former first lady have inspired unprecedented responses from the public, and attendance at the museum has more than doubled as visitors travel from near and far to view these larger-than-life paintings. The Obama Portraits is the first book about the making, meaning, and significance of these remarkable artworks. Richly illustrated with images of the portraits, exclu- sive pictures of the Obamas with the artists during their sittings, and photos of the historic unveiling ceremony by former White House photographer Pete Souza, this book offers insight into what these paintings can tell us about the history of portraiture and American culture. The volume also features a transcript of the unveiling ceremony, which includes moving remarks by the Obamas and the artists. A reversible dust jacket allows readers to choose which sitter to display on the front cover. An inspiring history of the creation and impact of the Obama portraits, this fascinating book speaks to the power of art—especially portraiture—to bring people together and promote cultural change. TAÍNA CARAGOL is curator of painting and sculpture and Latino art and history at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. DOROTHY MOSS is curator of painting and sculpture at the National Portrait Gallery, where she also directs the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition and serves as coordinating curator of the Smithsonian American Women’s A richly illustrated celebration of the History Initiative. -

The Avant-Garde { Katherine N

the avant-garde { Katherine N. Crowley Fine Art & Design } P ERIODIC J OURNAL V OLUME X III N O ’ S . 2 & 3 F EBRUARY / M ARCH 2 0 2 0 {amy sherald} by Katherine N. Crowley On February 12, 2018, the official portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama were publicly unveiled and Amy Sherald became, what appeared to be, an overnight sensation. The images were shared and re-tweeted across social media and attendance at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. increased by 300%. The reaction helped to advance the trajectory of Ms. Sherald’s fame but was, in reality, the next step in a career that has been built on years of hard work. “There’s been a lot of work that has not been accounted for, because for some reason the media wants to make it sound like it was a beautiful miracle, that I have a career now out of the blue—but no, it’s just from plain old perseverance,” she told Artnet® News in 2018. In 2018, the 100th anniversary of the Harlem Renaissance, I undertook a social media Amy Sherald was born in Columbus, Georgia in 1973. She received a campaign about African-American art history during the month of February. Each day Bachelor of Arts degree in painting I did a little online research, selected an artist, and posted a short biography with a in 1997 from Clark-Atlanta University link to Facebook and Twitter and added the hashtag #blackarthistorymonth. I enjoyed and was a Spelman College what I was learning and was introduced to the work of many new artists, both historic International Artist-in-Residence in and contemporary. -

Amy Sherald the Heart of the Matter

Press Release Amy Sherald the heart of the matter... Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street 10 September – 26 October 2019 ‘I look at America’s heart – people, landscapes, and cityscapes – and I see it as an opportunity to add to an American art narrative… I paint because I am looking for versions of myself in art history and in the world.’ – Amy Sherald New York... Amy Sherald documents contemporary black experience through arresting, otherworldly paintings. Drawing upon the American Realist tradition, she subverts the medium of portraiture to tease out unexpected narratives and situate black heritage centrally in the story of American art. With ‘the heart of the matter…,’ her inaugural exhibition with Hauser & Wirth, Sherald debuts a suite of new paintings that reinforces the multiplicities of African-American life and invites viewers to reconsider commonly accepted notions of race and representation. Informed by the artist’s reading of key texts that explore tensions between interior and public realms, ‘the heart of the matter…’ draws its title from the first chapter of bell hooks’ seminal book ‘Salvation,’ and builds on themes of silence and stillness explored in Kevin Quashie’s ‘Sovereignty of Quiet’ and U.S. Poet Laureate Elizabeth Alexander’s ‘Black Interior.’ In her new paintings, Sherald considers how these relate to the conceptualization of blackness as it is represented publicly, questioning representation of black identity, which often negates the complex reality of an interior life. She envisions black American identity beyond the conceits to which it has largely been restricted, attempting to restore a broader, fuller picture of humanity. -

The Magical Real-Ism of Amy Sherald

The Magical Real-ism of Amy Sherald February 3 – April 22, 2011 The Robert and Sallie Brown Gallery and Museum The Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History The Magical Real-ism of Amy Sherald About the exhibit Described by exhibition curator, Spelman College professor of art Dr. Arturo Lindsay, as “ground- ed in a self-reflective view of her life experiences as a young, black, Southern woman through the lenses of a post-modern intellectual,” Amy Sherald’s introspective oil paintings exclude the idea of color as race by removing “color” (skin tones are depicted in grayscale) but still portraying distinct physical indicators of race. The paintings, according to Sherald, “originated as a creation of a fairytale, illustrating an alternate existence in response to a dominant narrative of black history.” As the artist’s concepts became more coherent, her use of fantastical imagery evolved into scenes of spectacle, making direct reference to “blackness” and racialization. The result is an arresting series of paintings that blur preconceived notions of how “blackness” is defined within the context of American racial dogma. About the RobeRt And SAllie Brown GAlleRy And MuSeuM The Robert and Sallie Brown Gallery and Museum at the Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History is dedicated to the enrichment of visual culture on campus and in the com- munity. The Brown Gallery supports the Stone Center’s commitment to the critical examination of all dimensions of African-American and African diaspora cultures through formal exhibition of works of art, artifacts and material culture. hiStoRy And oveRview of the CenteR The Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History is part of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. -

Look at Me Now! Rashayla Marie Brown, Hassan Hajjaj, Rashid Johnson, Ebony G

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Look At Me Now! Rashayla Marie Brown, Hassan Hajjaj, Rashid Johnson, Ebony G. Patterson, Amy Sherald, William Villalongo on the wall Nina Chanel Abney porcelain projects William Villalongo, Water Root June 13 – August 23, 2015 Reception: Saturday, June 13, 4-7pm Artist talk: 4-5pm Moderated by Grace Deveney, MCA Chicago Susman Curatorial Fellow Curated by Allison Glenn CHICAGO – Monique Meloche Gallery is pleased to present, Look At Me Now!, a group exhibition of artists working internationally, who are presenting various perspectives on the history of portraiture through the construction of a new gaze. Throughout the exhibition, subtle hints of allegory give way to overt pop-culture references. It is through this lens that Rashayla Marie Brown, Hassan Hajjaj, Rashid Johnson, Ebony G. Patterson, Amy Sherald, William Villalongo, and Nina Chanel Abney produce, creating imagery that references, disarms, and reframes the canon of portraiture. Rashid Johnson’s Self-Portrait as the black Jimmy Connors in the finals of the New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club Summer Tennis Tournament was created for the artist’s 2008 solo exhibition at moniquemeloche. The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club is a fictional African American secret society, a parallel universe which embodies Johnson’s desire to upend the conventions of history and the idea of a legacy. Inspired by the construction and performance of identity, Amy Sherald paints portraits of strangers whose characteristics immediately resonate with her. Similarly influenced by the performance of identity, Rashayla Marie Brown works to reveal the projection of cultural myths and desires on the collective consciousness, often using her body as a source and subject.