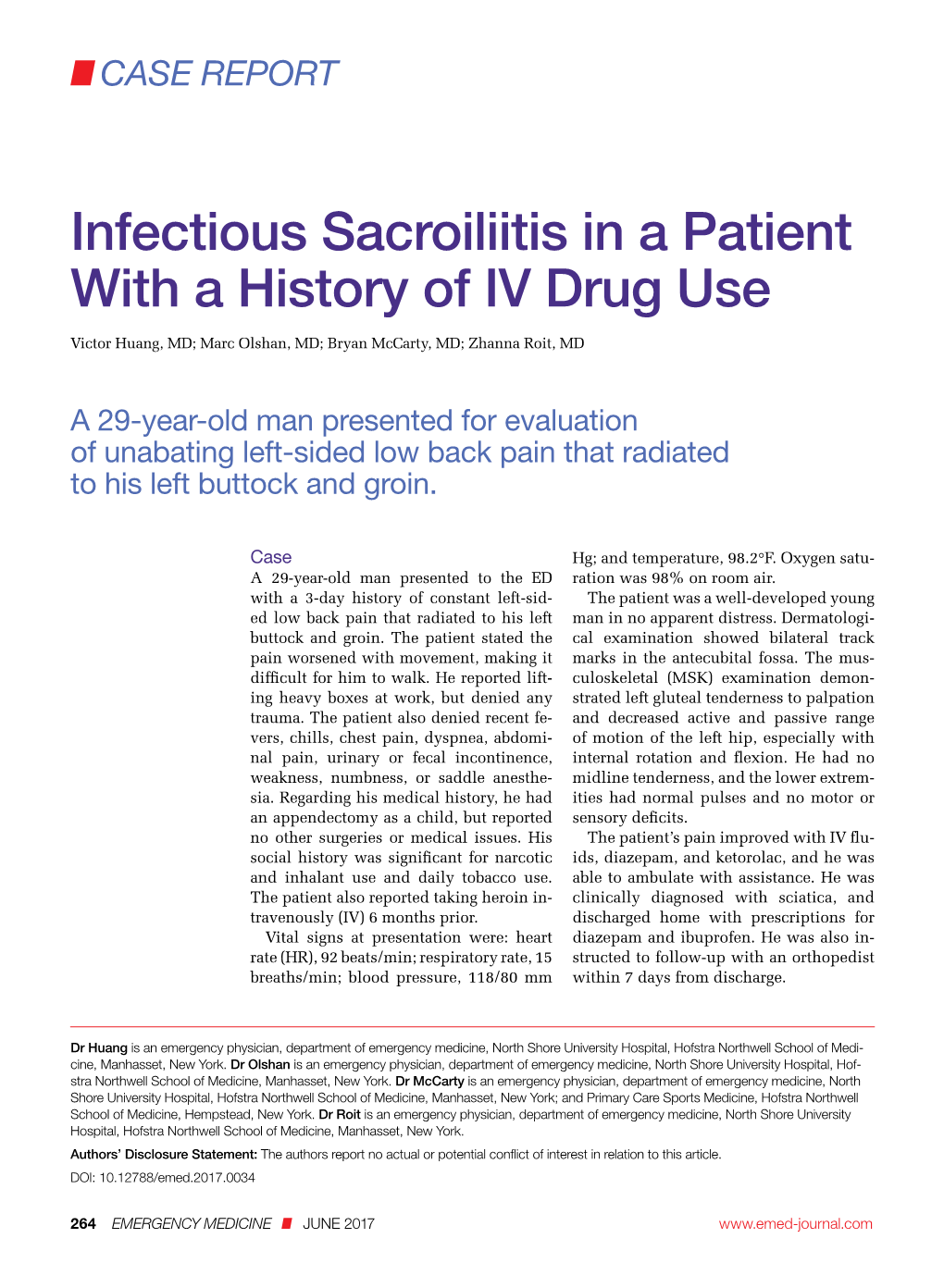

Infectious Sacroiliitis in a Patient with a History of IV Drug Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper Extremity

Upper Extremity Shoulder Elbow Wrist/Hand Diagnosis Left Right Diagnosis Left Right Diagnosis Left Right Adhesive capsulitis M75.02 M75.01 Anterior dislocation of radial head S53.015 [7] S53.014 [7] Boutonniere deformity of fingers M20.022 M20.021 Anterior dislocation of humerus S43.015 [7] S43.014 [7] Anterior dislocation of ulnohumeral joint S53.115 [7] S53.114 [7] Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, upper limb G56.02 G56.01 Anterior dislocation of SC joint S43.215 [7] S43.214 [7] Anterior subluxation of radial head S53.012 [7] S53.011 [7] DeQuervain tenosynovitis M65.42 M65.41 Anterior subluxation of humerus S43.012 [7] S43.011 [7] Anterior subluxation of ulnohumeral joint S53.112 [7] S53.111 [7] Dislocation of MCP joint IF S63.261 [7] S63.260 [7] Anterior subluxation of SC joint S43.212 [7] S43.211 [7] Contracture of muscle in forearm M62.432 M62.431 Dislocation of MCP joint of LF S63.267 [7] S63.266 [7] Bicipital tendinitis M75.22 M75.21 Contusion of elbow S50.02X [7] S50.01X [7] Dislocation of MCP joint of MF S63.263 [7] S63.262 [7] Bursitis M75.52 M75.51 Elbow, (recurrent) dislocation M24.422 M24.421 Dislocation of MCP joint of RF S63.265 [7] S63.264 [7] Calcific Tendinitis M75.32 M75.31 Lateral epicondylitis M77.12 M77.11 Dupuytrens M72.0 Contracture of muscle in shoulder M62.412 M62.411 Lesion of ulnar nerve, upper limb G56.22 G56.21 Mallet finger M20.012 M20.011 Contracture of muscle in upper arm M62.422 M62.421 Long head of bicep tendon strain S46.112 [7] S46.111 [7] Osteochondritis dissecans of wrist M93.232 M93.231 Primary, unilateral -

Transient Synovitis Or Septic Arthritis in Early Stage?

edicine: O M p y e c n n A e c g c r e e s s m E Emergency Medicine: Open Access Sekouris et al., Emergency Med 2014, 4:4 ISSN: 2165-7548 DOI: 10.4172/2165-7548.1000195 Short Communication Open Access Hip Pain in Children, a Diagnostic Challenge: Transient Synovitis or Septic Arthritis in Early Stage? Nick Sekouris*, Antonios Angoules, Dionysios Koukoulas and Eleni C Boutsikari Asssistant Director Orthopaedic, 'Metropolitan' Hospital, Athens, Greece *Corresponding author: Nick Sekouris, Asssistant Director Orthopaedic, 'Metropolitan' Hospital, Athens, Greece, Tel: +30 (210) 864 2202; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: April 27, 2014; Accepted date: June 13, 2014; Published date: June 17, 2014 Copyright: © 2014 Sekouris, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Short Communication symptoms, in case of SA, a destruction or dislocation of the femoral head or a widespread destruction of the femoral head and neck may be Hip pain in children is a diagnostic challenge for every practitioner visible radiographically. in emergency medicine and for any other doctor or health professional, facing this common symptom. Diagnosis may vary from Bone scintigraphy is neither sensitive nor specific enough in innocent conditions such as Transient Synovitis (TS), also mentioned distinguishing TS from SA and is not routinely used. Nevertheless, it as “irritable hip”, to hazardous for the child health diseases like Septic can diagnose multiple musculoskeletal lesions [7]. Arthritis (SA). -

Acetabular Labral Tears and Femoroacetabular Impingement

Michael J. Sileo, MD, FAAOS Sports Medicine Injuries Arthroscopic Shoulder, Knee & Hip Surgery December 7, 2018 NONE Groin and hip pain is common in athletes Especially hockey, soccer, and football 5% of all soccer injuries Renstrom et al: Br J Sports Med 1980. Complex anatomy and wide differential diagnoses that span multiple medical specialties make diagnosis difficult • Extra-articular causes: Muscle strain Snapping hip Adductor Trochanteric bursitis Iliopsoas Abductor tears Gluteus medius Compression neuropathies Hamstrings LFCN (meralgia paresthetica) Gracilis Sciatic nerve (Piriformis Avulsion injuries syndrome) Sports Hernia Ilioinguinal, Osteitis Pubis iliohypogastric, or genitofemoral nerve Intra-articular causes: Labral pathology Capsular laxity Femoroacetabular impingement Stress fracture Chondral pathology Septic arthritis Ligamentum teres injury Adhesive capsulitis Loose bodies Osteonecrosis Benign Intra-articular tumors SCFE PVNS Transient synovitis Synovial chondromatosis Soft-tissue injuries such as muscle strains and contusions are the most common causes of hip pain in the athlete It is important to be aware and suspicious of intra- articular causes of hip pain Up to 60% of athletes undergoing arthroscopy are initially misdiagnosed Delay to diagnosis is typically 7 months Labral pathology may not be diagnosed for up to 21 months Byrd et al: Clin Sports Med 2001. Burnett et al: JBJS 2006. Nature of discomfort Mechanical symptoms Stiffness Weakness Instability Location of discomfort -

Differential Diagnosis of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

pISSN: 2093-940X, eISSN: 2233-4718 Journal of Rheumatic Diseases Vol. 24, No. 3, June, 2017 https://doi.org/10.4078/jrd.2017.24.3.131 Review Article Differential Diagnosis of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Young Dae Kim1, Alan V Job2, Woojin Cho2,3 1Department of Pediatrics, Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Goyang, Korea, 2Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 3Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Montefiore Medical Center, New York, USA Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a broad spectrum of disease defined by the presence of arthritis of unknown etiology, lasting more than six weeks duration, and occurring in children less than 16 years of age. JIA encompasses several disease categories, each with distinct clinical manifestations, laboratory findings, genetic backgrounds, and pathogenesis. JIA is classified into sev- en subtypes by the International League of Associations for Rheumatology: systemic, oligoarticular, polyarticular with and with- out rheumatoid factor, enthesitis-related arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and undifferentiated arthritis. Diagnosis of the precise sub- type is an important requirement for management and research. JIA is a common chronic rheumatic disease in children and is an important cause of acute and chronic disability. Arthritis or arthritis-like symptoms may be present in many other conditions. Therefore, it is important to consider differential diagnoses for JIA that include infections, other connective tissue diseases, and malignancies. Leukemia and septic arthritis are the most important diseases that can be mistaken for JIA. The aim of this review is to provide a summary of the subtypes and differential diagnoses of JIA. (J Rheum Dis 2017;24:131-137) Key Words. -

Musculoskeletal Clinical Vignettes a Case Based Text

Leading the world to better health MUSCULOSKELETAL CLINICAL VIGNETTES A CASE BASED TEXT Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, RCSI Department of General Practice, RCSI Department of Rheumatology, Beaumont Hospital O’Byrne J, Downey R, Feeley R, Kelly M, Tiedt L, O’Byrne J, Murphy M, Stuart E, Kearns G. (2019) Musculoskeletal clinical vignettes: a case based text. Dublin, Ireland: RCSI. ISBN: 978-0-9926911-8-9 Image attribution: istock.com/mashuk CC Licence by NC-SA MUSCULOSKELETAL CLINICAL VIGNETTES Incorporating history, examination, investigations and management of commonly presenting musculoskeletal conditions 1131 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, RCSI Prof. John O'Byrne Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, RCSI Dr. Richie Downey Prof. John O'Byrne Mr. Iain Feeley Dr. Richie Downey Dr. Martin Kelly Mr. Iain Feeley Dr. Lauren Tiedt Dr. Martin Kelly Department of General Practice, RCSI Dr. Lauren Tiedt Dr. Mark Murphy Department of General Practice, RCSI Dr Ellen Stuart Dr. Mark Murphy Department of Rheumatology, Beaumont Hospital Dr Ellen Stuart Dr Grainne Kearns Department of Rheumatology, Beaumont Hospital Dr Grainne Kearns 2 2 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, RCSI Prof. John O'Byrne Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, RCSI Dr. Richie Downey TABLE OF CONTENTS Prof. John O'Byrne Mr. Iain Feeley Introduction ............................................................. 5 Dr. Richie Downey Dr. Martin Kelly General guidelines for musculoskeletal physical Mr. Iain Feeley examination of all joints .................................................. 6 Dr. Lauren Tiedt Dr. Martin Kelly Upper limb ............................................................. 10 Department of General Practice, RCSI Example of an upper limb joint examination ................. 11 Dr. Lauren Tiedt Shoulder osteoarthritis ................................................. 13 Dr. Mark Murphy Adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) ............................ 16 Department of General Practice, RCSI Dr Ellen Stuart Shoulder rotator cuff pathology ................................... -

Musculoskeletal Infections V1.1: ED Evaluation

Musculoskeletal Infections v1.1: ED Evaluation Approval & Citation Summary of Version Changes Explanation of Evidence Ratings PHASE I (E.D.) Abbreviations: Inclusion Criteria · Suspected septic arthritis and/or Septic Arthritis (SA) osteomyelitis in children > 3 months old Osteomyelitis (OM) Musculoskeletal (MSK) Exclusion Criteria · Permanent implanted orthopedic hardware ! · Symptoms at site contiguous with pressure ulcer/chronic wound For patients who · Suspected necrotizing soft tissue infection · Suspected axial skeletal involvement (i.e. are hemodynamically skull, spine, ribs, sternum) Kocher Criteria unstable or with sepsis · Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis physiology, also refer to · Immunocompromised patient (e.g. BMT, Predictors for SA of the hip: Septic Shock Pathway oncology, transplant) · Non-weight-bearing · Temp > 38.5C · ESR ≥ 40 mm/hr · WBC > 12,000 cells/mm3 Caird et al. introduced a fifth ED Team Assessment predictor for SA of the hip: · CRP > 2.0 mg/dL Evaluate for signs/symptoms suggestive of a primary MSK Infection ! Initial Workup Delayed diagnosis Labs: Order CBC with diff, CRP, ESR of hip SA can lead to avascular necrosis Microbiology: Consider aerobic + anaerobic blood cultures of the femoral head Imaging: Order x-ray of the involved bone/joint Low Clinical Suspicion Moderate/High Clinical Suspicion Alternative for SA and/or OM: for SA and/or OM: Unifying Diagnosis · Consider hip US if hip SA remains · Consult Orthopedics on the differential · Order hip US if hip SA is suspected · Consider alternative -

Common Pediatric MSK Complaints-When to Keep When to Refer

Common Pediatric MSK Complaints – when to keep, when to refer Michael J Conklin, MD I have no disclosures Content Low risk wrist fx’s Finger fractures Limping child Ankle sprains/fractures Back Pain Low risk wrist injuries Boutis randomized 96 kids 5-12 yoa into cast or splint group Transverse or greenstick fx’s of distal radius with <15 deg angulation Splint or cast 4 weeks and activity modification for 2 more weeks No difference in outcomes Scaphoid fx Before 15 yoa, 0.4% of pediatric fractures 0.45% of peds upper extremity fx’s 0.6/10,000 per year Snuff Box tenderness Initial films may be negative Most tx’d non-op with thumb spica cast Scaphoid – what to do If Snuff-box tender, place thumb spica splint and refer Finger fractures - Evaluation Tenderness/ swelling Deformity – coronal or rotational Resting cascade of digits Flexor and extensor tendon function Order xray of finger not hand Salter II phalanx fxs Minimally displaced Salter II of Phalanx – buddy tape or splint No need to refer Salter II phalanx fxs When more displaced, reduction is necessary. Then buddy tape Phalangeal neck fx Phalangeal neck fracture – can be unstable - Refer Seymour fx Seymour fx – Occult open fx – blood under nail plate or cuticle Needs local washout, nailbed repair and abx (Keflex) Refer Mallet finger Avulsion of extensor tendon from distal phalanx Refer Volar plate avulsion fx “Jammed finger” Hyperextension Dorsal extension block splint for 1 week then buddy tape No need to refer Limping Osteochondroses – Sever’s, Osgood- Schlatters Fractures that may be difficult to see on xray: Toddler’s fracture (tibia), Calcaneal tuberosity, Ist Metatarsal, Cuboid SCFE Transient synovitis Osteomyelitis/septic arthritis Evaluation History – Where is the pain? Duration? Fevers? Injury? Exam – gait evaluation, Trendelenberg gait vs. -

Limping Child

Case Report, Wolf et al Limping Child a b Molly Wolf, M.D. , Joseph Makris, M.D. a University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA b Department of Radiology, UMass Memorial Children’s Medical Center, Worcester, MA Case Presentation A previously healthy 27-month-old boy presented with a 3-day history of worsening right hip pain, fever of 103.1oF, decreased oral intake, and irritability. The patient recently recovered from an upper respiratory tract infection, but otherwise had no significant past medical history. On physical exam, the patient was unable to bear weight on the right leg and had decreased range of motion due to pain. Ultrasound detected a right hip joint effusion (Fig. 1A). The patient subsequently underwent aspiration and drainage of the right hip joint. Synovial fluid had an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count of 176,500/ mm3. Further analysis of the patient’s blood revealed an elevated WBC count, C reactive protein (CRP), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Culture from the synovial fluid subsequently grew Streptococcus Pneumoniae. MRI performed after the joint aspiration was significant for a small amount of residual joint fluid and normal bone marrow signal (Fig. 1B). Figure 1. (Above): (A) Sagittal ultrasound images of the right and left hips demonstrate a right hip joint effusion; the left side is normal. There is some debris within the right hip joint fluid; although not diagnostic, this raises the suspicion for septic arthritis. (B) FS T2 weighted image from an MRI of the right hip obtained after incision and drainage is significant for small residual right hip joint effusion, normal bone marrow signal, and no abscess. -

(AHO) And/Or Septic Arthritis Evidence-Based Guideline

DATE: November 2019 TEXAS CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL EVIDENCE-BASED OUTCOMES CENTER Acute Hematogenous Osteomyelitis (AHO) and/or Septic Arthritis Evidence-Based Guideline Definition: Acute hematogenous osteomyelitis (AHO) is Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) inflammation of the bone and bone marrow caused by an Reactive arthritis infectious organism that reaches the bone through the Post-infectious arthritis bloodstream; it is considered acute if a diagnosis is made Bone tumor (e.g., Ewing’s sarcoma, osteosarcoma) within 2-4 weeks of symptom onset. (1) Leukemia (e.g., acute lymphoblastic, acute myeloid) Septic arthritis is the infection of the joint, which can be caused Hemearthrosis (e.g., bleeding disorder) by bacteria, fungi, mycobacteria, or viruses. Spondylolisthesis Spondylolysis Pathophysiology: AHO is the most common form of osteomyelitis found in children; it occurs as the result of an Diagnostic Evaluation infection that spread through the bloodstream. The Clinicians should immediately refer to the Septic Shock pathophysiology and epidemiology of osteomyelitis are greatly guideline and intervene rapidly if patient has toxic appearance, influenced by the anatomy of the bone in pediatric patients. (2-4) ill appearance, altered mental status, and/or compromised The blood supply to the bone (nutrient artery) divides into a perfusion with abnormal vital signs. tortuous capillary bed that joins sinusoidal veins before entering the bone marrow of the metaphysis. The slow Table 1. Vital Sign Changes of Sepsis (6) movement of blood and lack of a reticuloendothelial lining Age Heart Rate Resp Rate Systolic BP Temp (°C) make it easy for bacteria to seed the bone and grow rapidly. 0d - 1m >205 >60 <60 <36 or >38 (2,4) The bacterial growth leads to cellulitis in the bone marrow >1m - 3m >205 >60 <70 <36 or >38 which then causes an inflammatory response. -

Hip Ultrasound

G Model EURR-5474; No. of Pages 8 ARTICLE IN PRESS European Journal of Radiology xxx (2011) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect European Journal of Radiology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ejrad Hip ultrasound Carlo Martinoli a,∗, Isabella Garello a, Alessandra Marchetti a, Federigo Palmieri a, Luisa Altafini a, Maura Valle b, Alberto Tagliafico c a Radiologia, DISC, Università di Genova, Largo Rosanna Benzi 8, I-16132 Genoa, Italy b Radiologia, Gaslini Children Hospital, Genova, Italy c Radiologia, National Institute for Cancer Research, Genoa, Italy article info abstract Article history: In newborns, US has an established role in the detection and management of developmental dys- Received 16 February 2011 plasia of the hip. Later in childhood, when the limping child is a major diagnostic dilemma, US is Accepted 22 March 2011 extremely helpful in the identification of the varied disease processes underlying this condition, as transient synovitis, septic arthritis, Perthes disease and slipped femoral capital epiphysis. In adoles- Keywords: cent practicing sporting activities, US is an excellent means to identify apophyseal injures about the Hip joint pelvic ring, especially when avulsions are undisplaced and difficult-to-see radiographically. Later on, in Ultrasound the adulthood, US is an effective modality to diagnose tendon and muscle injuries about the hip and Developmental dysplasia of the hip Irritable hip pelvis, identify effusion or synovitis within the hip joint or its adjacent bursae and guide the treatment Apophyseal injuries of these findings. The aim of this article is to provide a comprehensive review of the most common Hip tendon disorders pathologic conditions about the hip, in which the contribution of US is relevant for the diagnostic Hip joint synovitis work-up. -

The Limping Child Future of Pediatrics June 15, 2016

The Limping Child Future of Pediatrics June 15, 2016 Benjamin D. Martin Division of Orthopaedic Surgery The Limping Child • DDX • Normal Gait • Abnormal Gait Patterns • Common causes 2 HOW OLD IS THE CHILD? IS THE CHILD IN PAIN? PAINLESS PAINFUL Coxa vara Perthes DDH SCFE Leg length difference Discoid meniscus Cerebral palsy Transient synovitis Muscular dystrophy Septic arthritis Osteomyelitis JRA DON’T FORGET TO LOOK AT HIP FOR KNEE PAIN!! Toddler Child Adolescent (1-3) (4-10) (11-15) Transient synovitis Transient synovitis SCFE Septic Arthritis Septic Arthritis Dysplasia Toddler’s fx Perthes Tarsal coalition CP Leg length difference DDH Coxa vara JRA Normal Gait Efficient ?? Gait Analysis Toddler vs. Mature Gait step time cadence walking velocity COMMON GAIT PATTERNS Abnormal Gait Patterns • Antalgic • Trendeleburg • Proximal weakness • Spastic • Short limb Antalgic Gait Antalgic gait = shorten stance phase (amount of time affected limp on the ground) PAINFUL quick, soft steps Trendelenburg Gait Lever Arm Trendelenburg gait = body leans over weak abductors NOT PAINFUL* * Trendelenburg + pain = coxalgic gait Proximal Weakness Gait Weak hamstrings = lordosis Weak abductors = Trendelenburg 1st symptom might be toe walking! Spastic Gait Gross Motor & Functional Classification Delayed walkers? Short Limb Gait • Oblique pelvis • ASIS to medial malleolus • Femur vs. tibia vs. both 15 COMMON CONDITIONS Toxic Synovitis vs. Septic Arthritis Toxic Synovitis Septic Arthritis • 4 – 10 yo • Refusal to bear weight • NOT ALLOW MOTION • Hip pain, limp • Fevers (>38.5°) • Recent illness (URI) • WBC (>12K) • ESR (>40) • Low grade temps • CRP (>2) • Slightly elevated labs • Hematogenous spread • Aspirate • NSAIDs – Gram Stain, WBC>50K • Symptoms 1-2 weeks • Surgical emergency!! MOTRIN CHALLENGE ULTRASOUND (both have effusion) ASPIRATION Osteomyelitis subperiosteal abscess - Bone infection - Hematogenous - S. -

Strapping and Taping

Cigna Medical Coverage Policy- Therapy Services Strapping and Taping Effective Date: 5/15/2021 Next Review Date: 5/15/2022 INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE Cigna / ASH Medical Coverage Policies are intended to provide guidance in interpreting certain standard benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Please note, the terms of a customer’s particular benefit plan document may differ significantly from the standard benefit plans upon which these Cigna / ASH Medical Coverage Policies are based. In the event of a conflict, a customer’s benefit plan document always supersedes the information in the Cigna / ASH Medical Coverage Policy. In the absence of a controlling federal or state coverage mandate, benefits are ultimately determined by the terms of the applicable benefit plan document. Determinations in each specific instance may require consideration of: 1) the terms of the applicable benefit plan document in effect on the date of service 2) any applicable laws/regulations 3) any relevant collateral source materials including Cigna-ASH Medical Coverage Policies and 4) the specific facts of the particular situation Cigna / ASH Medical Coverage Policies relate exclusively to the administration of health benefit plans. Cigna / ASH Medical Coverage Policies are not recommendations for treatment and should never be used as treatment guidelines. Some information in these Coverage Policies may not apply to all benefit plans administered by Cigna. Certain Cigna Companies and/or lines of business only provide utilization review services to clients and