POP POWER: Pop Diplomacy for a Global Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

The White Animals

The 5outh 'r Greatert Party Band Playr Again: Narhville 'r Legendary White AniMalr Reunite to 5old-0ut Crowdr By Elaine McArdle t's 10 p.m. on a sweltering summer n. ight in Nashville and standing room only at the renowned Exit/In bar, where the crowd - a bizarre mix of mid Idle-aged frat rats and former punk rockers - is in a frenzy. Some drove a day or more to get here, from Florida or Arizona or North Carolina. Others flew in from New York or California, even the Virgin Islands. One group of fans chartered a jet from Mobile, Ala. With scores of people turned away at the door, the 500 people crushed into the club begin shouting song titles before the music even starts. "The White Animals are baaaaaaack!" bellows one wild-eyed thirty something, who appears mainstream in his khaki shorts and docksiders - until you notice he reeks of patchouli oil and is dripping in silver-and-purple mardi gras beads, the ornament of choice for White Animals fans. Next to him, a mortgage banker named Scott Brown says he saw the White Animals play at least 20 times when he was an undergrad at the University of Tennessee. He wouldn't have missed this long-overdue reunion - he saw both the Friday and Saturday shows - for a residential closing on Mar-A-Lago. Lead singer Kevin Gray, a one-time medical student who dropped his stud ies in 1978 to work in the band fulltime, steps onto the stage and peers out into the audience, recognizing faces he hasn't seen in more than a decade. -

Happily Ever Ancient

HAPPILY EVER ANCIENT Visions of Antiquity for children in visual media HAPPILY EVER ANCIENT This work is subject to an International Creative Commons License Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0, for a copy visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Visions of Antiquity for children in visual media First Edition, December 2020 ...still facing COVID-19. Editor: Asociación para la Investigación y la Difusión de la Arqueología Pública, JAS Arqueología Plaza de Mondariz, 6 28029 - Madrid www.jasarqueologia.es Attribution: In each chapter Cover: Jaime Almansa Sánchez, from nuptial lebetes at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, Greece. ISBN: 978-84-16725-32-8 Depósito Legal: M-29023-2020 Printer: Service Pointwww.servicepoint.es Impreso y hecho en España - Printed and made in Spain CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: A CONTEMPORARY ANTIQUITY FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG AUDIENCES IN FILMS AND CARTOONS Julián PELEGRÍN CAMPO 1 FAMILY LOVE AND HAPPILY MARRIAGES: REINVENTING MYTHICAL SOCIETY IN DISNEY’S HERCULES (1997) Elena DUCE PASTOR 19 OVER 5,000,000.001: ANALYZING HADES AND HIS PEOPLE IN DISNEY’S HERCULES Chiara CAPPANERA 41 FROM PLATO’S ATLANTIS TO INTERESTELLAR GATES: THE DISTORTED MYTH Irene CISNEROS ABELLÁN 61 MOANA AND MALINOWSKI: AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL APPROACH TO MODERN ANIMATION Emma PERAZZONE RIVERO 79 ANIMATING ANTIQUITY ON CHILDREN’S TELEVISION: THE VISUAL WORLDS OF ULYSSES 31 AND SAMURAI JACK Sarah MILES 95 SALPICADURAS DE MOTIVOS CLÁSICOS EN LA SERIE ONE PIECE Noelia GÓMEZ SAN JUAN 113 “WHAT A NOSE!” VISIONS OF CLEOPATRA AT THE CINEMA & TV FOR CHILDREN AND TEENAGERS Nerea TARANCÓN HUARTE 135 ONCE UPON A TIME IN MACEDON. -

Nowag Music Collection

Nowag Music Collection Processed by Alessandro Secino 2015 Memphis and Shelby County Room Memphis Public Library and Information Center 3030 Poplar Avenue Memphis, TN 38111 Nowag Music Collection Historical Sketch The Nowag-Williams talent agency operated during a time when the Memphis music scene was undergoing drastic changes. In 1975 Stax Records, a staple of the Memphis music industry, shut down. Two years later Elvis Presley was dead. It seemed that the bedrock of the Memphis music scene was being torn up during the late ‘70s. Disco, Punk, and Hip-Hop replaced the sounds of Blues, Soul, and Rock n’ Roll music across the country. Despite these changes in the Memphis music scene, Craig Nowag and his partner Bubba Williams, through the Nowag-Williams talent agency, kept the faltering music industry in Memphis going strong during a period of changing tastes and styles. The Nowag-Williams agency represented artists from all over the South, including bands such as Good Question, Delta, Joyce Cobb, Montage, and countless others. Between 1975 and 1978 the Nowag-Williams agency split, and Craig Nowag formed Craig Nowag’s National Artist Attractions. Nowag was widely respected in the music industry and was responsible for organizing the Pinebluff Freedom Festival, Graceland Nostalgia Festival, and performance deals with Sam’s Town Casino in Tunica Mississippi. Nowag was also enlisted to organize events for the Murfreesboro Chamber of Commerce, and the Arkansas Department of Parks & Tourism. One of Nowag’s more notable clients was British singer Peter Noone, formerly the lead of Herman’s Hermits, a band that was a big part of the British Invasion in the 1960s. -

The Music (And More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report

The Music (and More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report Report covers the time period of July 1st to Kieran Robbins & Chief - "Sway" [glam rock] September 30th, 2019. I inadvertently missed Troy a few before that time period, which were brought to my attention by fans, bands & Moriah Formica - "I Don't Care What You others. The missing are listed at the end, along with an Think" (single) [hard rock] Albany End Note… Nine Votes Short - "NVS: 09/03/2019" [punk rock] RECORDINGS: Albany Hard Rock / Metal / Punk Psychomanteum - "Mortal Extremis" (single track) Attica - "Resurected" (EP) [hardcore metal] Albany [thrash prog metal industrial] Albany Between Now and Forever - "Happy" (single - Silversyde - "In The Dark" [christian gospel hard rock] Mudvayne cover) [melodic metal rock] Albany Troy/Toledo OH Black Electric - "Black Electric" [heavy stoner blues rock] Scotchka - "Back on the Liquor" | "Save" (single tracks) Voorheesville [emo pop punk] Albany Blood Blood Blood - "Stranglers” (single) [darkwave Somewhere To Call Home - "Somewhere To Call Home" horror synthpunk] Troy [nu-metalcore] Albany Broken Field Runner – "Lay My Head Down" [emo pop Untaymed - "Lady" (single track) [british hard rock] punk] Albany / LA Colonie Brookline - "Live From the Bunker - Acoustic" (EP) We’re History - "We’re History" | "Pop Tarts" - [acoustic pop-punk alt rock] Greenwich "Avalanche" (singles) [punk rock pop] Saratoga Springs Candy Ambulance - "Traumantic" [alternative grunge Wet Specimens - "Haunted Flesh" (EP) [hardcore punk] rock] Saratoga Springs Albany Craig Relyea - "Between the Rain" (single track) Rock / Pop [modern post-rock] Schenectady Achille - "Superman (A Song for Mora)" (single) [alternative pop rock] Albany Dead-Lift - "Take It or Leave It" (single) [metal hard rock fusion] Schenectady Caramel Snow - "Wheels Are Meant To Roll Away" (single track) [shoegaze dreampop] Delmar Deep Slut - "u up?" (3-song) [punk slutcore rap] Albany Cassandra Kubinski - "DREAMS (feat. -

Controlling the Spreadability of the Japanese Fan Comic: Protective Practices in the Dōjinshi Community

. Volume 17, Issue 2 November 2020 Controlling the spreadability of the Japanese fan comic: Protective practices in the dōjinshi community Katharina Hülsmann, Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf, Germany Abstract: This article examines the practices of Japanese fan artists to navigate the visibility of their own works within the infrastructure of dōjinshi (amateur comic) culture and their effects on the potential spreadability of this form of fan comic in a transcultural context (Chin and Morimoto 2013). Beyond the vast market for commercially published graphic narratives (manga) in Japan lies a still expanding and particularizing market for amateur publications, which are primarily exchanged in printed form at specialized events and not digitally over the internet. Most of the works exchanged at these gatherings make use of scenarios and characters from commercially published media, such as manga, anime, games, movies or television series, and can be classified as fan works, poaching from media franchises and offering a vehicle for creative expression. The fan artists publish their works by making use of the infrastructure provided by specialized events, bookstores and online printing services (as described in detail by Noppe 2014), without the involvement of a publishing company and without the consent of copyright holders. In turn, this puts the artists at risk of legal action, especially when their works are referring to the content owned by notoriously strict copyright holders such as The Walt Disney Company, which has acquired Marvel Comics a decade ago. Based on an ethnographic case study of Japanese fan artists who create fan works of western source materials (the most popular during the observed timeframe being The Marvel Cinematic Universe), the article identifies different tactics used by dōjinshi artists to ensure their works achieve a high degree of visibility amongst their target audience of other fans and avoid attracting the attention of casual audiences or copyright holders. -

Travis Larson Band Travis Larson Band Travis Larson Band Travis Larson Band Travis Larson Band Travis Larson Band S S E R P S S E R P S S E R P S S E R P R P S Q a F

TRAVIS LARSON BAND TRAVIS LARSON BAND TRAVIS LARSON BAND TRAVIS LARSON BAND TRAVIS LARSON BAND TRAVIS LARSON BAND PRESS PRESS PRESS PRESS PR FAQS Travis Larson Band TRAVIS LARSON BAND TRAVIS LARSON BAND Guitar Player Magazine GP Editors' Top Three 2011 ES TRAVIS LARSON BAND Guitar Hero goes from tender to full throttle "Silky bends, sweet legato lines, and tuneful shred... instrumen- "...A smoking instrumental power trio...With tons of technique Burn Season (PRCN-1005) BURN SEASON Rockshow DVD SOUNDMIND (PRCN-1009) TRAVIS LARSON BAND Suspension tal rock fans should catch this guy." -Guitar Player Magazine to burn..." -Expose Magazine Precision Records (2004) Precision Records (2003) Itching for something that will sound as good Rock Show DVD Tracing the evolution of the rock guitar instrumentalist would probably start with Les Paul and S (Precision) Silky bends, sweet legato lines, and tuneful shred characterize Larson's playing speeding down the interstate as it does in your Guitar freaks Precision Records (PRCN-1004) move into the realm of the surf movement, the technical advances of Hendrix and Clapton, and “Melodically tasty, the playing is smoothly condent while "A lot of meat on the barbecue..." on these 12 cuts. Some stellar moments include the slick lines on the opener, home stereo system? Look no further than Burn Guitarist/keyboardist Travis Larson has a bit of Steve Morse have a new then into more modern axe grinders like Eric Johnson and Joe Satriani. Add to the stack a cat technically brilliant, and production is so sonically crisp the -Axe Magazine "Nevermore," the swooping whammy work on "Down on Victory," and the Season, the third studio album from the Travis sensibility to his technically nimble melodic/harmonic guitar work, With the release of their second full length CD Suspension, The Travis named Travis Larson, and you have yourself the ultimate guitar solo experience. -

Doraemon in India

Media Literacy in Entertainment for Children: The Fantastic Case of Doraemon in India Neha Hooda University of Debrecen, Hungary BRIEF SUMMARY ➤ Media consumption preferences of children in the age group of 8 to13 years in India ➤ Based on research conducted between Sept 2017 - 2018 ➤ Understand how media impacts everyday life for children on the basis of content they watched ➤ Interacted with 201 girls and 249 boys ➤ A total of 200 programs were sampled of which the case study elaborates on the top 5 programs popular between boys and girls. ➤ Today I will talk about 1 such program: Doraemon :-) DORAEMON: The Gadget Cat from the Future Telecasted in India since 2005 on Disney Channel WHO IS THIS CAT? ➤ Robotic cat who travels back in time from the 22nd century to help Nobita ➤ Keeps several gadgets (from the future) in his four- dimensional pocket ➤ Best gadgets: Bamboo- Copter & Anywhere Door ➤ Key characters - Doaremon, Nobita, Shizuka, Gian and Suneo ➤ Originally aimed at children in the ages of 3 years to 8 years ➤ The series is over 40 years old and still popular in Asia CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF DORAEMON ➤ The Cuddliest Hero in Asia”: Time magazine chose Doraemon as one of the 22 Asian heroes for the special issue of Asian Hero ➤ In 2008, Japan appointed Doraemon as nation's first "anime ambassador ➤ The Fujiko F. Fujio museum in Kawasaki showcases Doraemon as the key hero TIMELINE OF DORAEMON ➤ 1969: Written by Fujiko F. Fujio & first published as a manga comic ➤ 1973: First edition - 26 episodes broadcasted as an animated series for -

Liz Phair the Poptimist by Carrie Courogen

Liz Phair the Poptimist By Carrie Courogen HE EARLY AUGHTS WEREN'T exactly a medic}. landscape that Tendeared itself to my parents. It was the heyday of Total Request Live, when Britney became a ~'bad girl" and Christina joined her, when Hilary Duff turned her TV starpower into a music career, and Jessica Simpson turned her music career-into a TV show. Our TV was enforced by parental controls, and once Britney held that snake, my music television access was·limited to VHl, whose programming was heavy on aging seventies rock stars' safe, adult contemporary output and not much else. MTV had to be consumed in bits and pieces, after school a( friends' houses or sleepovers. It was during one of those covert viewings that I heard Liz Phair's "Extraordinary" for the first time. It felt like a revelation. ' . , h d fl t rodamation of Ph airs confidence was infectious; er e an P b · · · essage I'd yet to emg flawed but still spectacular was a nveting m re · c. • d and I consumed as ceive from a song. Toe pop music my inen s . • I5 tw l . 1h closest thing gir e Ve-year-olds lacked this sort of fe~hng. e . 5 Kelly our h . h at the tiOle wa age ad to an empowerment ant em . usic was Clarkso , " " B t Clarkson, whose Ill d ns Miss Independent. u as Iaunche fizzy . Her career w . and fun, was a reality show winner. · ) and call-in in p Of thern rnen art by a panel of three judges (two . -

Doraemon Game Apk Obb

Doraemon game apk obb Continue APKCombo Racing Games Nobeta sizuka Doraemon Download APK and OBB (35 MB) 1.0 Shanti bikash Chakma February 14, 2019 (2 years ago) Download APK and OBB (35MB) Download APK and OBB (35MB) Digital World Description Nobeta sizuka Doraemon We provide Nobeta sizuka Doraemon 1.0 APK and OBB file for Android 4.1 and above. Nobeta sizuka Doraemon is a free racing game. It's easy to download and install on your cell phone. Please note that ApkPlz only shares the original and free clean apk installer for Nobeta sizuka Doraemon 1.0 APK and OBB without any changes. The average score is 5.00 out of 5 stars in the playstore. If you want to learn more about Nobeta sizuka Doraemon, then you can visit Shanti Ikish Chakma Support Center for more information All apps and games here for home or personal use only. If any download apk infringes your copyright, please contact us. Nobeta sizuka Doraemon is a property and trademark from developer Shanti bikash chakma. It's a good game. Nobeta sizuka Doraemon Jiyan they all play this game every dayIt's a good game. Nobeta sizuka Doraemon Jiyan all they play this game every day Show more description Nobeta sizuka Doraemon Here we provide Nobeta sizuka Doraemon 1.0 APK and OBB file for Android 4.1 and above. Nobeta sizuka Doraemon is included in the Racing app store category. This is the newest and latest version of Nobeta sizuka Doraemon (com.wNobetaSizukaDoremon_8574162). It's easy to download and install on your cell phone. -

Vliv Anime Na Vznik a Formování Subkultury Otaku Bakalářská Diplomová Práce

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Seminář japonských studií Tereza Bělecká Vliv anime na vznik a formování subkultury otaku Bakalářská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Barbora Leštáchová 2014 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s využitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. Prohlašuji, že tištěná verze práce je shodná s verzí elektronickou. Souhlasím, aby práce byla archivována a zpřístupněna ke studijním účelům. ...................................................... Podpis autorky práce 2 Poděkování Zde bych chtěla poděkovat vedoucí práce Mgr. Barboře Leštáchové za veškerou pomoc a podnětné připomínky. 3 Obsah 1. Úvod .................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Vymezení vybraných pojmů ................................................................................................. 8 2.1 Anime ............................................................................................................................ 8 2.2 Subkultura ...................................................................................................................... 9 2.3 Otaku ............................................................................................................................10 3. Historie anime .....................................................................................................................12 3.1 Vznik moderního anime.................................................................................................12 -

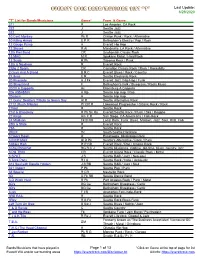

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020 "T" List for Bands/Musicians Genre* From & Genre 311 R Los Angeles, CA Rock 322 J Seattle Jazz 322 J Seattle Jazz 10 Cent Monkey Pk R Clinton Punk / Rock / Alternative 10 Killing Hands E P R Bellingham's Electro / Pop / Rock 12 Gauge Pump H Everett Hip Hop 12 Stones R Al Mandeville, LA Rock / Alternative 12th Fret Band CR Snohomish Classic Rock 13 MAG M R Spokane Metal / Hard Rock 13 Scars R Pk Tacoma Rock / Punk 13th & Nowhere R Everett Rock 2 Big 2 Spank CR Carnation Classic Rock / Rock / Rockabilly 2 Guys And A Broad B R C Everett Blues / Rock / Country 2 Libras E R Seattle Electronic Rock 20 Riverside H J Fk Everett Jazz / Hip Hop / Funk 20 Sting Band F Bellingham's Folk / Bluegrass / Roots Music 20/20 A Cappella Ac Ellensburg A Cappella 206 A$$A$$IN H Rp Seattle Hip Hop / Rap 20sicem H Seattle Hip Hop 21 Guns: Seattle's Tribute to Green Day Al R Seattle Alternative Rock 2112 (Rush Tribute) Pr CR R Lakewood Progressive / Classic Rock / Rock 21feet R Seattle Rock 21st & Broadway R Pk Sk Ra Everett/Seattle Rock / Punk / Ska / Reggae 22 Kings Am F R San Diego, CA Americana / Folk-Rock 24 Madison Fk B RB Local Rock, Funk, Blues, Motown, Jazz, Soul, RnB, Folk 25th & State R Everett Rock 29A R Seattle Rock 2KLIX Hc South Seattle Hardcore 3 Doors Down R Escatawpa, Mississippi Rock 3 INCH MAX Al R Pk Seattle's Alternative / Rock / Punk 3 Miles High R P CR Everett Rock / Pop / Classic Rock 3 Play Ricochet BG B C J Seattle bluegrass, ragtime, old-time, blues, country, jazz 3 PM TRIO