1 ALTERNATE TITLE JUNE 7, 1989: FILE to ALL AGENCIES Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

1 Hey Jude the Beatles 1968 2 Stairway to Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 3 Stayin' Alive Bee Gees 1978 4 YMCA Village People 1979 5

1 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 2 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 3 Stayin' Alive Bee Gees 1978 4 YMCA Village People 1979 5 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 6 Da Ya Think I'm Sexy? Rod Stewart 1979 7 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 8 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 9 Tragedy Bee Gees 1979 10 Le Freak Chic 1978 11 Macho Man Village People 1978 12 I Will Survive Gloria Gaynor 1979 13 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 14 Night Fever Bee Gees 1978 15 Fire Pointer Sisters 1979 16 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 17 Shake Your Groove Thing Peaches & Herb 1979 18 Hound Dog Elvis Presley 1956 19 Heartbreak Hotel Elvis Presley 1956 20 The Twist Chubby Checker 1960 21 Johnny B. Goode Chuck Berry 1958 22 Too Much Heaven Bee Gees 1979 23 Last Dance Donna Summer 1978 24 American Pie Don McLean 1972 25 Heaven Knows Donna Summer & Brooklyn Dreams 1979 26 Mack The Knife Bobby Darin 1959 27 Peggy Sue Buddy Holly 1957 28 Grease Frankie Valli 1978 29 Love Me Tender Elvis Presley 1956 30 Soul Man Blues Brothers 1979 31 You Really Got Me The Kinks 1964 32 Hot Blooded Foreigner 1978 33 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 34 Layla Derek & The Dominos 1972 35 September Earth, Wind & Fire 1979 36 Don't Be Cruel Elvis Presley 1956 37 Blueberry Hill Fats Domino 1956 38 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 39 Copacabana (At The Copa) Barry Manilow 1978 40 Shadow Dancing Andy Gibb 1978 41 Evergreen (Love Theme From "A Star Is Born") Barbra Streisand 1977 42 Miss You Rolling Stones 1978 43 Mandy Barry Manilow 1975 -

The White Animals

The 5outh 'r Greatert Party Band Playr Again: Narhville 'r Legendary White AniMalr Reunite to 5old-0ut Crowdr By Elaine McArdle t's 10 p.m. on a sweltering summer n. ight in Nashville and standing room only at the renowned Exit/In bar, where the crowd - a bizarre mix of mid Idle-aged frat rats and former punk rockers - is in a frenzy. Some drove a day or more to get here, from Florida or Arizona or North Carolina. Others flew in from New York or California, even the Virgin Islands. One group of fans chartered a jet from Mobile, Ala. With scores of people turned away at the door, the 500 people crushed into the club begin shouting song titles before the music even starts. "The White Animals are baaaaaaack!" bellows one wild-eyed thirty something, who appears mainstream in his khaki shorts and docksiders - until you notice he reeks of patchouli oil and is dripping in silver-and-purple mardi gras beads, the ornament of choice for White Animals fans. Next to him, a mortgage banker named Scott Brown says he saw the White Animals play at least 20 times when he was an undergrad at the University of Tennessee. He wouldn't have missed this long-overdue reunion - he saw both the Friday and Saturday shows - for a residential closing on Mar-A-Lago. Lead singer Kevin Gray, a one-time medical student who dropped his stud ies in 1978 to work in the band fulltime, steps onto the stage and peers out into the audience, recognizing faces he hasn't seen in more than a decade. -

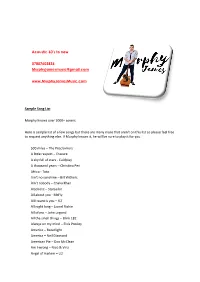

Sample Song List Murphy Knows Over 2000+ Covers. Here Is Sample List Of

Acoustic 60’s to now 07807603836 [email protected] www.MurphyJamesMusic.com Sample Song List Murphy knows over 2000+ covers. Here is sample list of a few songs but there are many more that aren't on this list so please feel free to request anything else. If Murphy knows it, he will be sure to play it for you. 500 miles – The Proclaimers A little respect – Erasure A sky full of stars - Coldplay A thousand years – Christina Peri Africa - Toto Ain't no sunshine – Bill Withers Ain’t nobody – Chaka Khan Alcoholic – Starsailor All about you - McFly All I want is you – U2 All night long – Lionel Richie All of me – John Legend All the small things – Blink 182 Always on my mind – Elvis Presley America – Razorlight America – Neil Diamond American Pie – Don McClean Am I wrong – Nico & Vinz Angel of Harlem – U2 Angels – Robbie Williams Another brick in the wall – Pink Floyd Another day in Paradise – Phil Collins Apologize – One Republic Ashes – Embrace A sky full of stars - Coldplay A-team - Ed Sheeran Babel – Mumford & Sons Baby can I hold you – Tracy Chapman Baby I love your way – Peter Frampton Baby one more time – Britney Spears Babylon – David Gray Back for good – Take That Back to black – Amy Winehouse Bad moon rising – Credence Clearwater Revival Be mine – David Gray Be my baby – The Ronettes Beautiful noise – Neil Diamond Beautiful war – Kings of Leon Best of you – Foo Fighters Better – Tom Baxter Big love – Fleetwood Mac Big yellow taxi – Joni Mitchell Black and gold – Sam Sparro Black is the colour – Christie Moore Bloodstream -

David Bowie's Urban Landscapes and Nightscapes

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 17 | 2018 Paysages et héritages de David Bowie David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.13401 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Jean Du Verger, “David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text”, Miranda [Online], 17 | 2018, Online since 20 September 2018, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.13401 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text 1 David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger “The Word is devided into units which be all in one piece and should be so taken, but the pieces can be had in any order being tied up back and forth, in and out fore and aft like an innaresting sex arrangement. This book spill off the page in all directions, kaleidoscope of vistas, medley of tunes and street noises […]” William Burroughs, The Naked Lunch, 1959. Introduction 1 The urban landscape occupies a specific position in Bowie’s works. His lyrics are fraught with references to “city landscape[s]”5 and urban nightscapes. The metropolis provides not only the object of a diegetic and spectatorial gaze but it also enables the author to further a discourse on his own inner fragmented self as the nexus, lyrics— music—city, offers an extremely rich avenue for investigating and addressing key issues such as alienation, loneliness, nostalgia and death in a postmodern cultural context. -

On Their Best Behavior

C M Y K www.newssun.com EWS UN NHighlands County’s Hometown-S Newspaper Since 1927 ‘The Lorax’ Two at a time? Dowtown plans GOP Puzzle Dr. Seuss classic County hears about Chamber hopes A look at the party’s hits the big screen biennial budgeting to liven up Mall fractured factions REVIEW, 11B PAGE 2A PAGE 9A PAGE 12B Friday-Saturday, March 2-3, 2012 www.newssun.com Volume 93/Number 30 | 50 cents Inside George Blvd. picked for new HCSO site By ED BALDRIDGE “We’re going to get to $11 “Hear me out,” Handley Handley put the Restoration [email protected] million to $12 million on this said after another estimate of Church on State Road 66 back on the SEBRING — Commissioners somehow. That’s the gun bar- potentially $7 million was table because it “has all the site work decided Tuesday to move forward rel I’m looking down,” said given for a separate Crime finished.” Unknown Soldiers with a new sheriff’s building at Commissioner Don Elwell. Lab/Property and Evidence Handley suggested that the build- George Boulevard, but not without After several hours of site Facility at Kenilworth ing could be purchased for $2 mil- some backtracking. discussions and costs compar- Boulevard, changes to the lion, has 32,000 square-feet and is Where’s the Benton outrage over Early in the discussion, estimates isons, Commissioner Ron existing jail facility and the structurally sound which could trans- of the cost for construction more than Handley threw the idea of another proposed new 20,000 square-foot late into cost savings for the county. -

Im a Believer: My Life of Monkees, Music, and Madness Free

FREE IM A BELIEVER: MY LIFE OF MONKEES, MUSIC, AND MADNESS PDF Micky Dolenz,Mark Bego | 272 pages | 01 Jun 2004 | Cooper Square Publishers Inc.,U.S. | 9780815412847 | English | Lanham, United States Should You Take the Monkees Seriously? | Music Aficionado Starring Davy Jones, Micky Dolenz, Peter Tork and Michael Nesmith, The Monkees was a TV show about a struggling rock group that featured early incarnations of music videos and plenty of family-friendly psychedelic vibes. Following its to run, the series gained new generations of fans through marathon airings on MTV and Nickelodeon in the s. As a cast member of the Broadway musical Oliver! But probably the craziest part of this story was how the year-old Brit was completely oblivious to who John, Paul, George and Ringo were. He only Im a Believer: My Life of Monkees interest in what they were doing because he wanted to figure out how to make girls scream too. So the ad they took out in the September 8, edition of Variety had to reflect the attitudes of the burgeoning youth culture. In JuneThe Monkees headed off to Paris for a season two episode that would ostensibly show them being mobbed by French fans. Toward and Madness end of the second and final season, Peter Tork and Micky Dolenz were Music the opportunity to direct an episode. Tork, using his full name in the credits—Peter H. The Monkees would officially be canceled later that year. Once atthen again at Yes, you read that correctly. Inthe year of Sgt. Probably because neither British band had a hit TV show on its hands. -

1 Stairway to Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 2 Hey Jude the Beatles 1968

1 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 2 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 3 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 5 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 6 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 7 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 8 Peggy Sue Buddy Holly 1957 9 Imagine John Lennon 1971 10 Johnny B. Goode Chuck Berry 1958 11 Born In The USA Bruce Springsteen 1985 12 Happy Together The Turtles 1967 13 Mack The Knife Bobby Darin 1959 14 Brown Sugar Rolling Stones 1971 15 Blueberry Hill Fats Domino 1956 16 I Heard It Through The Grapevine Marvin Gaye 1968 17 American Pie Don McLean 1972 18 Proud Mary Creedence Clearwater Revival 1969 19 Let It Be The Beatles 1970 20 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 1972 21 Light My Fire The Doors 1967 22 My Girl The Temptations 1965 23 Help! The Beatles 1965 24 California Girls Beach Boys 1965 25 Born To Be Wild Steppenwolf 1968 26 Take It Easy The Eagles 1972 27 Sherry Four Seasons 1962 28 Stop! In The Name Of Love The Supremes 1965 29 A Hard Day's Night The Beatles 1964 30 Blue Suede Shoes Elvis Presley 1956 31 Like A Rolling Stone Bob Dylan 1965 32 Louie Louie The Kingsmen 1964 33 Still The Same Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1978 34 Hound Dog Elvis Presley 1956 35 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 36 Tears Of A Clown Smokey Robinson & The Miracles 1970 37 Addicted To Love Robert Palmer 1986 38 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 39 Layla Derek & The Dominos 1972 40 The House Of The Rising Sun The Animals 1964 41 Don't Be Cruel Elvis Presley 1956 42 The Sounds Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 1966 43 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 44 Old Time Rock And Roll Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1979 45 Heartbreak Hotel Elvis Presley 1956 46 Jump (For My Love) Pointer Sisters 1984 47 Little Darlin' The Diamonds 1957 48 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 1971 49 Night Moves Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1977 50 Oh, Pretty Woman Roy Orbison 1964 51 Ticket To Ride The Beatles 1965 52 Lady Styx 1975 53 Good Vibrations Beach Boys 1966 54 L.A. -

Dancing in My Underwear

Dancing in My Underwear The Soundtrack of My Life By Mike Morsch Copyright© 2012 Mike Morsch i Dancing in My Underwear With love for Judy, Kiley, Lexi, Kaitie and Kevin. And for Mom and Dad. Thanks for introducing me to some great music. Published by The Educational Publisher www.EduPublisher.com ISBN: 978-1-62249-005-9 ii Contents Foreword By Frank D. Quattrone 1 Chapters: The Association Larry Ramos Dancing in my underwear 3 The Monkees Micky Dolenz The freakiest cool “Purple Haze” 9 The Lawrence Welk Show Ken Delo The secret family chip dip 17 Olivia Newton-John Girls are for more than pelting with apples 25 Cheech and Chong Tommy Chong The Eighth-Grade Stupid Shit Hall of Fame 33 iii Dancing in My Underwear The Doobie Brothers Tom Johnston Rush the stage and risk breaking a hip? 41 America Dewey Bunnell Wardrobe malfunction: Right guy, right spot, right time 45 Three Dog Night Chuck Negron Elvis sideburns and a puka shell necklace 51 The Beach Boys Mike Love Washing one’s hair in a toilet with Comet in the middle of Nowhere, Minnesota 55 Hawaii Five-0 Al Harrington Learning the proper way to stretch a single into a double 61 KISS Paul Stanley Pinball wizard in a Mark Twain town 71 The Beach Boys Bruce Johnston Face down in the fields of dreams 79 iv Dancing in My Underwear Roy Clark Grinnin’ with the ole picker and grinner 85 The Boston Pops Keith Lockhart They sound just like the movie 93 The Beach Boys Brian Wilson Little one who made my heart come all undone 101 The Bellamy Brothers Howard Bellamy I could be perquaded 127 The Beach Boys Al Jardine The right shirt at the wrong time 135 Law & Order Jill Hennessy I didn’t know she could sing 143 Barry Manilow I right the wrongs, I right the wrongs 151 v Dancing in My Underwear A Bronx Tale Chazz Palminteri How lucky can one guy be? 159 Hall & Oates Daryl Hall The smile that lives forever 167 Wynonna Judd I’m smelling good for you and not her 173 The Beach Boys Jeffrey Foskett McGuinn and McGuire couldn’t get no higher . -

Nowag Music Collection

Nowag Music Collection Processed by Alessandro Secino 2015 Memphis and Shelby County Room Memphis Public Library and Information Center 3030 Poplar Avenue Memphis, TN 38111 Nowag Music Collection Historical Sketch The Nowag-Williams talent agency operated during a time when the Memphis music scene was undergoing drastic changes. In 1975 Stax Records, a staple of the Memphis music industry, shut down. Two years later Elvis Presley was dead. It seemed that the bedrock of the Memphis music scene was being torn up during the late ‘70s. Disco, Punk, and Hip-Hop replaced the sounds of Blues, Soul, and Rock n’ Roll music across the country. Despite these changes in the Memphis music scene, Craig Nowag and his partner Bubba Williams, through the Nowag-Williams talent agency, kept the faltering music industry in Memphis going strong during a period of changing tastes and styles. The Nowag-Williams agency represented artists from all over the South, including bands such as Good Question, Delta, Joyce Cobb, Montage, and countless others. Between 1975 and 1978 the Nowag-Williams agency split, and Craig Nowag formed Craig Nowag’s National Artist Attractions. Nowag was widely respected in the music industry and was responsible for organizing the Pinebluff Freedom Festival, Graceland Nostalgia Festival, and performance deals with Sam’s Town Casino in Tunica Mississippi. Nowag was also enlisted to organize events for the Murfreesboro Chamber of Commerce, and the Arkansas Department of Parks & Tourism. One of Nowag’s more notable clients was British singer Peter Noone, formerly the lead of Herman’s Hermits, a band that was a big part of the British Invasion in the 1960s. -

The Music (And More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report

The Music (and More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report Report covers the time period of July 1st to Kieran Robbins & Chief - "Sway" [glam rock] September 30th, 2019. I inadvertently missed Troy a few before that time period, which were brought to my attention by fans, bands & Moriah Formica - "I Don't Care What You others. The missing are listed at the end, along with an Think" (single) [hard rock] Albany End Note… Nine Votes Short - "NVS: 09/03/2019" [punk rock] RECORDINGS: Albany Hard Rock / Metal / Punk Psychomanteum - "Mortal Extremis" (single track) Attica - "Resurected" (EP) [hardcore metal] Albany [thrash prog metal industrial] Albany Between Now and Forever - "Happy" (single - Silversyde - "In The Dark" [christian gospel hard rock] Mudvayne cover) [melodic metal rock] Albany Troy/Toledo OH Black Electric - "Black Electric" [heavy stoner blues rock] Scotchka - "Back on the Liquor" | "Save" (single tracks) Voorheesville [emo pop punk] Albany Blood Blood Blood - "Stranglers” (single) [darkwave Somewhere To Call Home - "Somewhere To Call Home" horror synthpunk] Troy [nu-metalcore] Albany Broken Field Runner – "Lay My Head Down" [emo pop Untaymed - "Lady" (single track) [british hard rock] punk] Albany / LA Colonie Brookline - "Live From the Bunker - Acoustic" (EP) We’re History - "We’re History" | "Pop Tarts" - [acoustic pop-punk alt rock] Greenwich "Avalanche" (singles) [punk rock pop] Saratoga Springs Candy Ambulance - "Traumantic" [alternative grunge Wet Specimens - "Haunted Flesh" (EP) [hardcore punk] rock] Saratoga Springs Albany Craig Relyea - "Between the Rain" (single track) Rock / Pop [modern post-rock] Schenectady Achille - "Superman (A Song for Mora)" (single) [alternative pop rock] Albany Dead-Lift - "Take It or Leave It" (single) [metal hard rock fusion] Schenectady Caramel Snow - "Wheels Are Meant To Roll Away" (single track) [shoegaze dreampop] Delmar Deep Slut - "u up?" (3-song) [punk slutcore rap] Albany Cassandra Kubinski - "DREAMS (feat.