1927 Himalayan Letters of Gypsy Davy and Lady Ba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Statistical Handbook 2016-17

1 2 C ONVERSION F ACTOR Length Inch 25.4 Millimeters 1 1 Mile 1.61 Kilometers 1 Millimeter 0.04 Inch 1 Centimeter 0.39370 Inch 1 Meter 1.094 Yards 1 Kilometer 0.62137 Miles 1 Yard 0.914 Meters 5 ½ Yards 1 Rod/Pole/Perch 22 Yards 1 Chain 20.17 Meters 1 Chain 220 Yards 1 Furlong 8 Furlong 1 Mile 8 Furlong 1.609 Kilometers 3 Miles 1 League Area 1 Marla 272 Sq. Feet 20 Marlas 1 Kanal 1 Acre 8 Kanal 1 Hectare 20 Kanal (Apox.) 1 Hectare 2.47105 Acre 1 Sq. Mile 2.5900 Sq. Kilometer 1 Sq. Mile 640 Acre 1 Sq. Mile 259 Hectares 1 Sq. Yard 0.84 Sq. Meter 1 Sq. Kilometer 0.3861 Sq. Mile 1 Sq. Kilometer 100 Hectares 1 Sq. Meter 1.196 Sq. Yards Capacity 1 Imperial Gallon 4.55 Litres 1 Litre 0.22 Imperial Gallon 3 Weight 1 Ounce (Oz) 28.3495 Grams 1 Pound 0.45359 Kilogram 1 Long Ton 1.01605 Metric Tone 1 Short Ton 0.907185 Metric Tone 1 Long Ton 2240 Pounds 1 Short Ton 2000 Pounds 1 Maund 82.2857 Pounds 1 Maund 0.037324 Metric Tone 1 Maund 0.3732 Quintal 1 Kilogram 2.204623 Pounds 1 Gram 0.0352740 Ounce 1 Gram 0.09 Tolas 1 Tola 11.664 Gram 1 Ton 1.06046 Metric Tone 1 Tonne 10.01605 Quintals 1 Meteric Tonne 0.984207 Tons 1 Metric Tonne 10 Quintals 1 Metric Ton 1000 Kilogram 1 Metric Ton 2204.63 Pounds 1 Metric Ton 26.792 Maunds (standard) 1 Hundredweight 0.508023 Quintals 1 Seer 0.933 Kilogram Bale of Cotton (392 lbs.) 0.17781 Metric Tonne 1 1 Metric Tonne 5.6624 Bale of Cotton (392 lbs.) 1 Metric Tonne 5.5116 Bale of Jute (400 lbs.) 1 Quintals 100 Kilogram 1 Bale of jute (400 lbs.) 0.181436 Metric Volume 1 Cubic Yard 0.7646 Cubic Meter 1 Cubic Meter -

The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications

The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications By Name: Syeda Batool National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad April 2019 1 The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications by Name: Syeda Batool M.Phil Pakistan Studies, National University of Modern Languages, 2019 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY in PAKISTAN STUDIES To FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, DEPARTMENT OF PAKISTAN STUDIES National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad April 2019 @Syeda Batool, April 2019 2 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES THESIS/DISSERTATION AND DEFENSE APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have read the following thesis, examined the defense, are satisfied with the overall exam performance, and recommend the thesis to the Faculty of Social Sciences for acceptance: Thesis/ Dissertation Title: The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications Submitted By: Syed Batool Registration #: 1095-Mphil/PS/F15 Name of Student Master of Philosophy in Pakistan Studies Degree Name in Full (e.g Master of Philosophy, Doctor of Philosophy) Degree Name in Full Pakistan Studies Name of Discipline Dr. Fazal Rabbi ______________________________ Name of Research Supervisor Signature of Research Supervisor Prof. Dr. Shahid Siddiqui ______________________________ Signature of Dean (FSS) Name of Dean (FSS) Brig Muhammad Ibrahim ______________________________ Name of Director General Signature of -

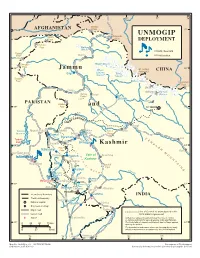

Download Deployment Map.Pdf

73o 74o 75o 76o 77o 78o Mintaka 37o AFGHANISTAN Pass 37o --- - UNMOGIP Darkot Khunjerab Pass Pass DEPLOYMENT - Thui- An Pass Batura- Glacier UN HQ / Rear HQ Chumar Khan- Baltit UN field station Pass Shandur- Hispar Glacier Pass 36o 36o Jammu Chogo Mt. Godwin CHINA Lungma Austin (K2) Gilgit Biafo 8611m Glacier Glacier Dadarili Baltoro Glacier Pass Karakoram Pass Sia La - Chilas Bilafond La Siachen Nanga Astor Glacier Parbat -- 8126m Skardu PAKISTAN Goma Babusar-- 35o Pass and 35o NJ 980420 X Kel ONTR C O F L LINE O - s a r Kargil D Tarbela Muzaffarabad- Tithwal- Wular Zoji La Dras- Reservoir Sopur Lake Pass Domel J h Jhe ---- e am Baramulla a m Z - Leh Tarbela A Dam Uri Srinagar- N Chakothi Kashmir S o o 34 K - 34 Haji-- Pir A - R Rawalakot Pass P - - - i- Karu Campbellpore Islamabad r M - O Titrinot P Vale of Anantnag Islamabad--- Poonch U a Kashmir N Mendhar n T Rawalpindi- Kotli j - A a- Banihal I ch l Pass N - n u R S P Rajouri C a n hen - Mangla g e ab Reservoir Naushahra- - Mangla Dam New Mirpur- Riasi 33o Munawwarwali- 33o - Jhelum Tawi Bhimber Chhamb Udhampur Akhnur- NW 605550 X International boundary Jammu INDIA - b Provincial boundary - na Gujrat he C - National capital Sialkot- Samba City, town or village Major road Kathua Line of Control as promulgated in the Lesser road 1972 SIMLA Agreement -- vi Airport Gujranwala Ra Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. 32o The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not been agreed 32o 0 25 50 75 km upon by the parties. -

HM 14 APRIL Page 3.Qxd

THE HIMALAYAN MAIL Q JAMMU Q WEDNESDAY Q APRIL 14, 2021 JAMMU & KASHMIR 3 Div Com visits Mukhdoom Sahab Siachen warriors celebrates ‘Siachen Day’ HIMALAYAN MAIL NEWS Shrine, Chatti Padshahi JAMMU, APR 13 On 13 April 2021, Siachen Gurudwara, Ganpatyar Temple Warriors celebrated the 37th Siachen Day with place for devotees, visiting tremendous zeal and enthu- during the festival days. siasm. Brigadier Gurpal He said that today's festi- Singh, SM laid a wreath on vals which are being cele- behalf of GOC, Fire & Fury brated with harmony and Corps and paid homage to brotherhood adds colour to the martyrs at the Siachen its festivity. He said these War Memorial, Base Camp festivals strengthen the to commemorate their bonds of love among people courage and fortitude in se- and nurture amity and har- curing the highest and cold- mony in J&K. est battlefield of the World. During the visit, the com- On this day in 1984, In- mittees of places apprised dian troops first unfurled not only in the face of enemy Soldier continues to guard Siachen Warriors who the Div Com about their is- the tri colour at Bilafond La but also in the face of icy the Frozen Frontier with de- served their motherland sues and demands. He gave launching Operation Megh- peaks with extreme termination and resolve while successfully thwarting HIMALAYAN MAIL NEWS Padshahi Rainawari and arrangements being put in patient hearing to them as- doot. Since then, it has been weather. against all odds. The enemy designs over the SRINAGAR, APR 13 extended his greetings on place for the Holy month of suring that all their genuine a saga of valour and audacity To this day, the Siachen Siachen Day honours all the years. -

General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 14 Points of Jinnah (March 9, 1929) Phase “II” of CDM

General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 1 www.teachersadda.com | www.sscadda.com | www.careerpower.in | Adda247 App General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 Contents General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................ 3 Indian Polity for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .................................................................................................. 3 Indian Economy for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ........................................................................................... 22 Geography for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .................................................................................................. 23 Ancient History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................................ 41 Medieval History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .......................................................................................... 48 Modern History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................................ 58 Physics for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .........................................................................................................73 Chemistry for AFCAT II 2021 Exam.................................................................................................... 91 Biology for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ....................................................................................................... 98 Static GK for IAF AFCAT II 2021 ...................................................................................................... -

Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring

SANDIA REPORT SAND2007-5670 Unlimited Release Printed September 2007 Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring Brigadier (ret.) Asad Hakeem Pakistan Army Brigadier (ret.) Gurmeet Kanwal Indian Army with Michael Vannoni and Gaurav Rajen Sandia National Laboratories Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550 Sandia is a multiprogram laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company, for the United States Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. Approved for public release; further dissemination unlimited. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. Printed in the United States of America. -

Three Visions of Rimo III 8000Ers

20 T h e A l p i n e J o u r n A l 2 0 1 3 Ten minutes after news of the pair’s success was communicated from the summit to basecamp, Agnieszka Bielecka got a radio message from Gerf- ried Göschl’s team to say they were camped about 300m below the summit SIMON YEARSLEY, MALCOLM BASS and preparing to set off. Making the summit bid Göschl himself, Swiss & RACHEL ANTILL aspirant guide Cedric Hahlen, and Nisar Hussain Sadpara, one of three professional Pakistani mountaineers to have climbed all five Karakoram Three Visions of Rimo III 8000ers. None of them was heard from or seen again. Adam Bielecki and Janusz Golab had reached the 8068m top of Gasherbrum I at 8.30am on 9 March; their novel tactic for winter high altitude climbing of leaving camp at midnight had worked. But the weather window was about to close. They descended speedily but with great care, reaching camp III at 1pm, by which time the weather had seriously deteriorated. Pressing on, they arrived at Camp II at about 5pm, ‘slightly frostbitten and very happy’. On 10 March all four members of the Polish team reached base- camp; both summiteers were suffering from second-degree frostbite, Adam Bielecki to his nose and feet, Janusz Golab to his nose. With concern mounting for Göschl, Hahlen and Nisar Hussain, a rescue helicopter was called, however poor weather stalled any flights until The Polish Gasherbrum team.(Adam Bielecki) the 15th when Askari Aviation was able to fly to 7000m and study the route. -

Factsthat Led to the Creation of Pakistan

AVAIL YOUR COPY NOW! April-July 2020 Volume 17 No. 2-3 `100.00 (India-Based Buyer Only) SP’s Military Yearbook 2019 SP’s AN SP GUIDE P UBLICATION www.spsmilitaryyearbook.com WWW.SPSLANDFORCES.COM ROUNDUP THE ONLY MAGAZINE IN ASIA-PACIFIC DEDICATED to LAND FORCES IN THIS ISSUE >> LEAD STORY ILLuSTratioN: SP Guide Publications / Vipul PAGE 3 Lessons from Ladakh Standoff Wakhan Corridor Territory ceded We keep repeating the mistakes. The by Pakistan to CLASHES ALONG Chinese PLA incursion in Ladakh, across the China in 1963 LAC, has been again a collective intelligence (Shaksgam Valley) failure for India. There is much to be CHINA THE LAC learned for India from the current scenario. Teram Shehr Lt General P.C. Katoch (Retd) May 5 Indian and Gilgit Siachen Glacier Chinese soldiers PAGE 4 Pakistan clash at Pangong TSO lake. Disengagement to Demobilisation: Occupied Karakorm Resetting the Relations Pass May 10 Face-off at China is a master of spinning deceit Kashmir the Muguthang Valley and covert action exploiting strategy Baltistan in Sikkim. Skardu and statecraft as means of “Combative Depsang La May 21 Chinese coexistence” with opponents. Throughout Bilafond La NJ 9842 Aksai Chin troops enter into the their history Chinese have had their share Patrol Galwan River Valley of brutal conflicts at home and with Point 14 in Ladakh region. neighbours. LOC Zoji La Kargil Nubra Valley Galwan Valley May 24 Chinese Lt General J.K. Sharma (Retd) Line Of Pangong-TSO camps at 3 places: Control Leh Lake Hotspring, P14 and PAGE 5 P15. Way Ahead for the Indian Armed Forces Jammu & Shyok LADAKH June 15 Violent Face- Kashmir off” between Indian and Chinese Soldiers. -

Cartes De Trekking LADAKH & ZANSKAR Trekking Maps

Cartes de trekking LADAKH & ZANSKAR Trekking Maps Index des noms de lieux Index of place names NORTH CENTER SOUTH abram pointet www.abram.ch Ladakh & Zanskar Cartes de trekking / Trekking Maps Editions Olizane A Arvat E 27 Bhardas La C 18 Burma P 11 Abadon B 1 Arzu N 11 Bhator D 24 Burshung O 19 Abale O 5 Arzu N 11 Bhutna A 19 C Abran … Abrang Arzu Lha Khang N 11 Biachuthasa A 7 Cerro Kishtwar C 19 Abrang C 16 Ashur Togpo H 8 Biachuthusa … Biachuthasa Cha H 20 Abuntse D 7 Askuta F 11 Biadangdo G 3 Cha H 20 Achina Lungba D 6 Askuta Togpo F 11 Biagdang Gl. G 2 Cha Gonpa H 20 Achina Lungba Gonpa D 6 Ating E 17 Biama … Beama Chacha Got C 26 Achina Thang C 7 Ayi K 3 Biar Malera A 24 Chacham Togpo K 14 Achina Thang Gonpa D 7 Ayu M 11 Biarsak F 2 Chachatapsa D 7 Achinatung … Achina Thang B Bibcha F 19 Chagangle V 24 Achirik I 11 Bagioth F 27 Bibcha Lha Khang F 19 Chagar Tso S 12 Achirik Lha Khang I 11 Bahai Nala B 22 Bidrabani Sarai A 22 Chagarchan La U 24 Agcho C 15 Baihali Jot C 25 Bilargu D 5 Chagdo W 9 Agham O 8 Bakartse C 16 Billing Nala G 27 Chaghacha E 9 Agsho B 17 Bakula Bao I 13 Bima E 27 Chaglung C 7 Agsho Gl. B 17 Baldar Gl. B 13 Birshungle V 26 Chagra U 11 Agsho La B 17 Baldes B 5 Bishitao A 22 Chagra U 11 Agyasol A 19 Baleli Jot E 22 Bishur B 25 Chagri F 9 Ajangliung J 7 Balhai Nala C 25 Bod Kharbu C 8 Chagtsang M 15 Akeke R 18 Balthal Got C 26 Bog I 27 Chagtsang La M 15 Akling L 11 Bangche Togpo G 15 Bokakphule V 27 Chakharung B 5 Aksaï Chin V 10 Bangche Togpo F 14 Boksar Gongma F 13 Chakrate T 16 Alam H 12 Bangongsho X 16 Boksar Yokma G 13 Chali Gali E 27 Alchi I 10 Banku G 8 Bolam L 11 Chaluk J 13 Alchi H 10 Banon D 23 Bong La M 21 Chalung U 21 Alchi Brok H 10 Banraj Gl. -

Volume 27 # June 2013

THE HIMALAYAN CLUB l E-LETTER Volume 27 l June 2013 Contents Annual Seminar February 2013 ........................................ 2 First Jagdish Nanavati Awards ......................................... 7 Banff Film Festival ................................................................. 10 Remembrance George Lowe ....................................................................................... 11 Dick Isherwood .................................................................................... 3 Major Expeditions to the Indian Himalaya in 2012 ......... 14 Himalayan Club Committee for the Year 2013-14 ........... 28 Select Contents of The Himalayan Journal, Vol. 68 ....... 30 THE HIMALAYAN CLUB l E-LETTER The Himalayan Club Annual Seminar 2013 The Himalayan Club Annual Seminar, 03 was held on February 6 & 7. It was yet another exciting Annual Seminar held at the Air India Auditorium, Nariman Point Mumbai. The seminar was kicked off on 6 February 03 – with the Kaivan Mistry Memorial Lecture by Pat Morrow on his ‘Quest for the Seven and a Half Summits’. As another first the seminar was an Audio Visual Presentation without Pat! The bureaucratic tangles had sent Pat back from the immigration counter of New Delhi Immigration authorities for reasons best known to them ! The well documented AV presentation made Pat come alive in the auditorium ! Pat is a Canadian photographer and mountain climber who was the first person in the world to climb the highest peaks of seven Continents: McKinley in North America, Aconcagua in South America, Everest in Asia, Elbrus in Europe, Kilimanjaro in Africa, Vinson Massif in Antarctica, and Puncak Jaya in Indonesia. This hour- long presentation described how Pat found the resources to help him reach and climb these peaks. Through over an hour that went past like a flash he took the audience through these summits and how he climbed them in different parts of the world. -

1 Ministry of Environment and Forests Wildlife Section ************ Minutes

Ministry of Environment and Forests Wildlife Section ************ Minutes of the meeting of the Standing Committee of National Board for Wildlife (14th meeting) held on 4th May 2009 in Paryavaran Bhavan under the Chairmanship of Hon’ble Minister of State(Forests and Wildlife.) A meeting of the Standing Committee of NBWL was convened on the 4th May 2009 in Room No. 403, Paryavaran Bhawan, New Delhi, under the Chairmanship of Hon'ble Minister of State for Environment & Forests (Forests & Wildlife). At the outset, Hon'ble Chairman welcomed all the members and informed that considering the urgency and strategic importance of border roads, this meeting had been convened. He appreciated the cooperation provided by both the official as well as the non- official members in the meetings of the Standing Committee of NBWL held in the past. The Chairman hoped that the delegates realize the strategic importance of the border roads, especially under the present circumstances when the country is facing threats to its national integrity from all quarters. It was followed by discussions on the agenda items as follows: Agenda item No. 1: Confirmation of minutes of the 13th meeting of Standing Committee of NBWL held on 12th December 2008 The Member-Secretary informed that the minutes of the 13 th meeting of Standing Committee of NBWL held on 12.12.2008 were circulated to the members on 12 th January 2009. He also informed that no comments have been received in this context. In view of this, the Committee unanimously confirmed the minutes of the last meeting without making any change. -

Demilitarization of Siachen Glacier and Its Implications on the Defence Budget of Pakistan

Journal of Politics and International Studies Vol. 2, No. 1, January –June 2016, pp. 01– 12 Demilitarization of Siachen Glacier and Its Implications on the Defence Budget of Pakistan Sanam Ahmed Khawaja PhD Scholar Department of Political Science, University of the Punjab, Lahore ABSTRACT This research paper focuses on demilitarization of Siachen Glacier and its implications on the defence budget of Pakistan. The government of India and Pakistan are hiking the defence budget to an extreme and in particular for Siachen that consequently it reveals that the glacier of Siachen retain massive geo- strategic significance for both the states. The data has been collected from primary and secondary sources. Moreover theory of disarmament has been adopted by the researcher in relation to Siachen conflict. An interview was conducted from military personnel to get aware of military’s stance with reference to Siachen Glacier. Thus it has been concluded that mutually both the states ought to look for an amicable solution as regard to glacier’s demilitarization furthermore generate a balance between defence and other main sectors so they might not face any negligence. Keywords: Budget of Pakistan, Siachen Glacier, Demilitarization Introduction Geographical Location of the Glacier Siachen Glacier said to be as the “world’s highest battlefield” is ranked as the second longest non- polar glacier after the Fedchenko Glacier in the Pamir which is 77km long. The 70km long glacier of Siachen is located in the Eastern Karakoram Range and width of it lies in between 2 to 8 km and total area is less than 1,000sq km.