Analysis of Represented Purchasing Skills in Academic Literature and in Current Dutch Education Provision at Universities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CGMA COMPETENCY FRAMEWORK the CGMA COMPETENCY FRAMEWORK IS COMPRISED of FOUR KNOWLEDGE AREAS Technical Skills, Business Skills, People Skills and Leadership Skills

CGMA COMPETENCY FRAMEWORK THE CGMA COMPETENCY FRAMEWORK IS COMPRISED OF FOUR KNOWLEDGE AREAS Technical Skills, Business Skills, People Skills and Leadership Skills. These knowledge areas are underpinned by ethics, integrity and professionalism. This downloadable document is the complete version of the CGMA Competency Framework. Apply accounting In the context and finance of the business skills And lead within the organisation CGMA COMPETENCY FRAMEWORK — PROFICIENCY LEVELS FOUNDATIONAL: This requires a basic understanding of the business structures, operations and financial performance, and includes responsibility for implementing and achieving results through own actions rather than through others. INTERMEDIATE: This requires a moderate understanding of overall business operations and measurements, including responsibility for monitoring the implementation of strategy. This has limited or informal responsibility for colleagues and/or needs to consider broader approaches or consequences. ADVANCED: This requires strong understanding of the organisation’s environment, current strategic position and direction with strong analytical skills and the ability to advise on strategic options for the business. This includes formal responsibility for colleagues and their actions; and that their decisions have a wider impact. EXPERT: This requires expert knowledge to develop strategic vision and provide unique insight to the overall direction and success of the organisation. This has formal responsibility for business areas and his/her actions and decisions -

Organizational Culture and Knowledge Management Success at Project and Organizational Levels in Contracting Firms

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PolyU Institutional Repository This is the Pre-Published Version. Organizational Culture and Knowledge Management Success at Project and Organizational Levels in Contracting Firms Patrick S.W. Fong1 and Cecilia W.C. Kwok2 ABSTRACT This research focuses on contracting firms within the construction sector. It characterizes and evaluates the composition of organizational culture using four culture types (Clan, Adhocracy, Market, and Hierarchy), the strategic approach for knowledge flow, and the success of KM systems at different hierarchical levels of contracting organizations (project and parent organization level). Responses from managers of local or overseas contracting firms operating in Hong Kong were collected using a carefully constructed questionnaire survey that was distributed through electronic mail. The organizational value is analyzed in terms of the four cultural models. Clan culture is found to be the most popular at both project and organization levels, which means that the culture of contracting firms very much depends on honest communication, respect for people, trust, and cohesive relationships. On the other hand, Hierarchy 1 Associate Professor, Department of Building & Real Estate, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong (corresponding author). T: +(852) 2766 5801 F: +(852) 2764 5131 E-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Building & Real Estate, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong. 1 culture, which focuses on stability and continuity, and analysis and control, seems to be the least favored at both levels. Another significant finding was that the two main KM strategies for knowledge flow, Codification and Personalization, were employed at both project and organization levels in equal proportion. -

The Impact of Digital Technology on Skills in Logistics Warehouses Mathieu Hocquelet

The impact of digital technology on skills in logistics warehouses Mathieu Hocquelet To cite this version: Mathieu Hocquelet. The impact of digital technology on skills in logistics warehouses. Training & Employment, Centre d’études et de recherches sur les qualifications (Céreq), 2020, 145, 4 p. halshs- 02975508 HAL Id: halshs-02975508 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02975508 Submitted on 22 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 145 TRAINING & 2020 EMPLOYMENT French Centre for Research on Education, Training and Employment The impact of digital technology on skills in logistics warehouses Driven by both technological developments and the boom in e-commerce, the logistics sector is currently undergoing far-reaching changes in its production processes. These Mathieu HOCQUELET (Céreq) dynamics could well lead to radical changes in working and employment conditions in a sector in which the demand for manual labour is very high. This edition of Training & Employment addresses the various challenges – including digitalisation, the sector’s attractiveness to workers and skill and career management – that French warehouses and logistics platforms are currently having to face. t the interface between manufacturing and the frequently cyclical nature of business. -

7 Burning Questions in Skills Management Contents

7 Burning Questions in Skills Management Contents 03 Introduction 04 How Do We Know What Skills We Should Be Tracking? 06 How Do We Think About Soft Skills? 09 How Do We Get Our Leaders Speaking The Same Language? 12 How Do We Inventory Skills Without Causing Anxiety? 14 How Wo We Incentivize Our People To Keep Their Skills Up To Date? 16 How Can We Be More Objective When Making Human Capital Decisions? 18 Won‘t This Take Forever To Roll Out? 20 Conclusion Introduction At Visual Workforce, our vision is a world where decisions about human capital are grounded in data – not gut. We are committed to building a revolutionary SaaS product that allows organizations to automate the capture of critical skills and capabilities data, and provide business leaders with clear insight into their people through powerful visualizations. We believe that organizations that take a data-driven approach to managing their workforce will be the ones that thrive in this period of great change. In today’s global economy, businesses need every edge they can get to stay competitive – they need to optimize every dollar, get more out of every employee, and build an organization that is truly resilient to change. We have spent years working with business leaders, consultants, managers, and HR professionals; and, along the way, we have heard some of the same questions again and again. In this eBook, we pull back the curtain and talk through some of the most common, pressing questions that face anyone considering a skills management initiative. Whether you have been down this road before or are just getting started, this eBook will have helpful tips and tricks, best practices, and recommendations so you can make more informed human capital decisions and maximize the value of your greatest asset – your people. -

Diversity and Inclusion Framework for Emergency Management Policy and Practice

ISILC INSTITUTE FOR SUSTAINABLE INDUSTRIES AND LIVEABLE CITIES bnhcrc.com.au DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION FRAMEWORK FOR EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT POLICY AND PRACTICE Celeste Young and Roger Jones Victoria University Version Release history Date 1.0 Initial release of publication 20/08/2020 All material in this document, except as identified below, is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International Licence. Material not licensed under the Creative Commons licence: • Department of Industry, Innovation and Science logo • Cooperative Research Centres Programme logo • Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC logo • Victoria University logo • All photographs, graphics and figures. All content not licensed under the Creative Commons licence is all rights reserved. Permission must be sought from the copyright owner to use this material. Disclaimer: Victoria University and the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC advise that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, Victoria University and the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC (including its employees and consultants) exclude all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. Publisher: Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC August 2020 Citation: Young C and Jones RN (2020) Diversity and inclusion framework for emergency management policy and practice, Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC, Melbourne. -

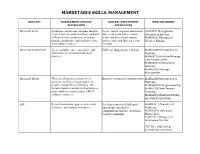

Marketable Skills: Management

MARKETABLE SKILLS: MANAGEMENT SKILL SET MANAGEMENT-SPECIFIC GENERAL EMPLOYMENT HOW DELIVERED APPLICATION APPLICATION Microsoft Excel Synthesize and present consumer insights Create, format, organize and present COSC3311 Management derived from the analysis of large amounts data, create pivot tables, combo, Information Systems of Point of Sale, syndicated, secondary scatter and pivot charts; import, MANA4315 Managerial primary, quantitative and qualitative data harvest, parse and filter data; write Decision Making from multiple sources. formulas. Microsoft PowerPoint Create factually correct, persuasive and Public speaking and presentation. MANA1300 Introduction to informative presentations using best Business practices. MANA3170 Build and Manage a Successful Career MANA3312 International Business MANA4395 Strategic Management Microsoft Word Write in a fluent style using correct Business writing and communication. MANA1300 Introduction to grammar, spelling and punctuation to Business produce various forms of writing. This MANA3325 Entrepreneurship includes business writing such as business MANA4320 New Venture plans, market research reports, SWOT Planning analysis reports, etc… MANA3370 Business Writing and Oral Presentation SAP Record transactions, process orders and Develop a variety of skills and MARK3311 Principles of deliveries, and manage inventories. knowledge essential to Marketing organizations that use enterprise MANA3305 Operations resource planning. Management COSC3311 Management Information Systems (UT Tyler-SAP student acknowledgment -

0- 1 Introduction to Developing Management Skills

0- 1 INTRODUCTION TO DEVELOPING MANAGEMENT SKILLS THE CRITICAL ROLE OF MANAGEMENT SKILLS No one doubts that the 21st century will continue to be characterized by chaotic, transformational, rapid- fire change. In fact, almost no sane person is willing to predict what the world will be like 50, 25, or even 15 years from now. Change is just too rapid and ubiquitous. The development of “nanobombs” have caused some people to predict that personal computers and desk top monitors will land on the scrap heap of obsolesce within 20 years. The new computers will be a product of etchings on molecules leading to personalized data processors injected in the bloodstream, implanted in eyeglasses, or included in wristwatches. Predictions of the changes that will occur in the future are often notoriously wrong, of course, as illustrated by Charles Watson’s (founder of IBM) prediction that only a few dozen computers would ever be needed in the entire world, Thomas Edison’s prediction that the light bulb would never catch on, or Irving Fisher’s (pre-eminent Yale economist) prediction in 1929 that the stock market had reached “a permanently high plateau.” When Neil Armstrong walked on the moon in 1969, most people predicted that we would soon be walking on Mars, establishing colonies in outer space, and launching probes from lunar pads. In 1973 with gas lines escalating due to an OPEC-led fuel crisis, economists predicted that gasoline would sell for $100 a barrel in the United States by 1980. At the beginning of the century, the figure was around $25. -

Manage and Anticipate Skills in Distribution Logistics: « For

International Journal of Business & Economic Strategy (IJBES) ISSN: 2356-5608, pp.38 -41 Manage and anticipate skills in distribution logistics: « For Moroccan autonomous administrations» Fatima IBNCHAHID¹, Saïd BALHADJ² ¹ PhD Student 2nd year at the national school of management, Tangier, [email protected], Tél: 06 30 18 21 19 ² Research professor at the national school of management, Tangier, [email protected], Tél: 05 39 31 34 87 University Abdelmalek Essâadi, the National School of Management Tangier, Morocco, Research Group in Management and Information Systems (GREMSI). Abstract: Under the same title, the recruitment or It is used under the Main functions that should social relations, the management of competences has assume the HRDs, Such As The recruitment, become essential for managers in human resource compensation, training, Career Management. .Both, to maintain the competitiveness of the company The Management of skills involves and secure professional career paths for employees. identifying the necessary skills for a good operation The company considers the employee as an actor of its professional project, that’s why it should be of the company; they are presented in three criteria enable them to develop their employability. functions: When we talk about management , it is Common competences: concerning all jobs of the automatically means the term training because it is company, it reflects the required skills to solve the the pillar of development of skills and competences, problems exceeding specifications of the job to skill/competence is not a given, it is built and become know its environment, exchange, be autonomous. training activities that should be strengthened to be Managerial skills: it refers to the required exist in the present and in the future as well . -

Banking & Financial Services Job Skills & Competencies Framework

IBM Analytics Datasheet Banking & Financial Services Job Skills & Competencies Framework A description of skills and competencies specific to Banking and Financial services. IBM recognizes that the Banking sector faces dynamic For more than 20 years, the IBM Kenexa Talent talent and skills management issues. These issues may Frameworks has been deployed in many organizations to sometimes appear tactical, but can also have wide ranging help them - either independently or as part of a larger HR impact on the successful and continuing operations of the strategy - improve learning, development and overall business. Through a structured approach to performance of a company’s most critical components. capturing the skills and talent required, you can capture, Using the content library is a rapid and robust way to recognize and manage risk against such issues as: customize your organizationally aligned competencies and • Product innovation job profiles. • Oversight and regulatory compliance • Sales production IBM Kenexa Talent Frameworks offers Job Skills & • Customer service Competencies across 18 different industries. This is but • Industry consolidation, mergers and acquisitions one of those libraries. Kenexa offers complete solutions to • Retail and investment services support your Talent Management requirements including cloud based software to manage your workforce Job Skills In an organization it may be easy to answer a question & Competencies, Employee Self-Assessment, Manager such as “How many new accounts were opened?” or Assessment, Skills Gap analysis and more. “What is our trading position today?”, but the same cannot be said when asked of knowledge, skills or people. Using a Job and Competency Framework, you will be able to lay a foundation for answering: • How many people and who and where are the ones with critical skills to support a new product? • What is it that top producers do best? Replicate and recruit to best performance standards. -

HRM's Role in Corporate Social and Environmental Sustainability

EPG SHRM Foundation’s Effective Practice Guidelines Series HRM’s Role in Corporate Social and Environmental Sustainability Produced in partnership with the World Federation of People Management Associations (WFPMA) and the North American Human Resource Management Association (NAHRMA) HRM’s Role in Corporate Social and Environmental Sustainability This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information regarding the subject matter covered. Neither the publisher nor the author is engaged in rendering legal or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent, licensed professional should be sought. Any federal and state laws discussed in this book are subject to frequent revision and interpretation by amendments or judicial revisions that may significantly affect employer or employee rights and obligations. Readers are encouraged to seek legal counsel regarding specific policies and practices in their organizations. This book is published by the SHRM Foundation, an affiliate of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM®). The interpretations, conclusions and recommendations in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the SHRM Foundation. ©2012 SHRM Foundation. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. This publication may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the SHRM Foundation, 1800 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA 22314. Selection of report topics, treatment of issues, interpretation and other editorial decisions for the Effective Practice Guidelines series are handled by SHRM Foundation staff and the report authors. -

“Leader's Interpersonal Skills and Its Effectiveness at Different Levels Of

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 4 [Special Issue - February 2012] “Leader’s Interpersonal Skills and Its Effectiveness at different Levels of Management” Aamir Khan Dr. Wisal Ahmad Institute of Management Science Kohat University of Science & Technology Bannu Road off Jerma, Kohat, KPK Pakistan Abstract This research study analyzed Leader’s Interpersonal skills (Ability to Motivate, Communicate, and Build Team) and its effectiveness at different levels of Management. Literature showed that these skills are important to be effective leader but it didn’t show that which skill is more important at different levels of management. For this purpose questionnaire was distributed to 150 employees in diverse departments in Kohat University of science and technology includes Top level, Middle level and Lower level employees. Descriptive tests of means and ANOVA were used as the most appropriate statistical techniques to analyze that which skill is more important at different levels of management. The results of this study found that at Top level of management leader’s ability to Build Team is more important as compared to Middle level of management but did not significantly differ as compared to Low level of management. At Middle level hypothesis was not supported (i.e. Ability to Communicate was not most necessary to be effective at Middle level of management). At Low level of management leader’s ability to Motivate is more important as compared to Middle level of management but did not significantly differ as compared to Top level of management. KEYWORDS: Ability to Motivate, Ability to Communicate, Ability to Build Team, Levels of Management 1. -

Rural Realities Is Published by the Rural Sociological Society, 104 Gentry Hall, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211-7040

Volume 1 | Issue 3 ����� ���������© 2006, Rural Sociological Society Community Emergency Response Teams: From Disaster Responders to Community Builders By Courtney Flint and Mark Brennan In brief... Community Emergency Response Teams (CERTs) – local residents trained as first responders to natural disasters – can also be used to help build community capacity before disasters strike. The CERTs framework for pulling together localities to prepare for disasters can also be mobilized to focus attention on other pressing issues in local areas. In communities with less capacity, CERT programs can provide a roadmap for how people and organizations can organize themselves to address important local issues and challenges To be effective in developing community capacity, CERTs must: • Involve diverse groups of residents and ensure balanced community representation • Get back to basics – CERTs have lately focused almost exclusively on major natural disasters and terrorist acts. However, they were originally designed to respond to a variety of local emergencies and serve as a broad-based conduit for community development and civic engagement. • Update training: Community development and civic engagement training should be the cornerstone of all CERT programs • Expand the view of what constitutes a disaster: rapid economic decline or environmental change can also be disastrous for rural areas The federal government should: • Re-evaluate the role and position of FEMA and the CERT Program within the Department of Homeland Security • Re-evaluate the