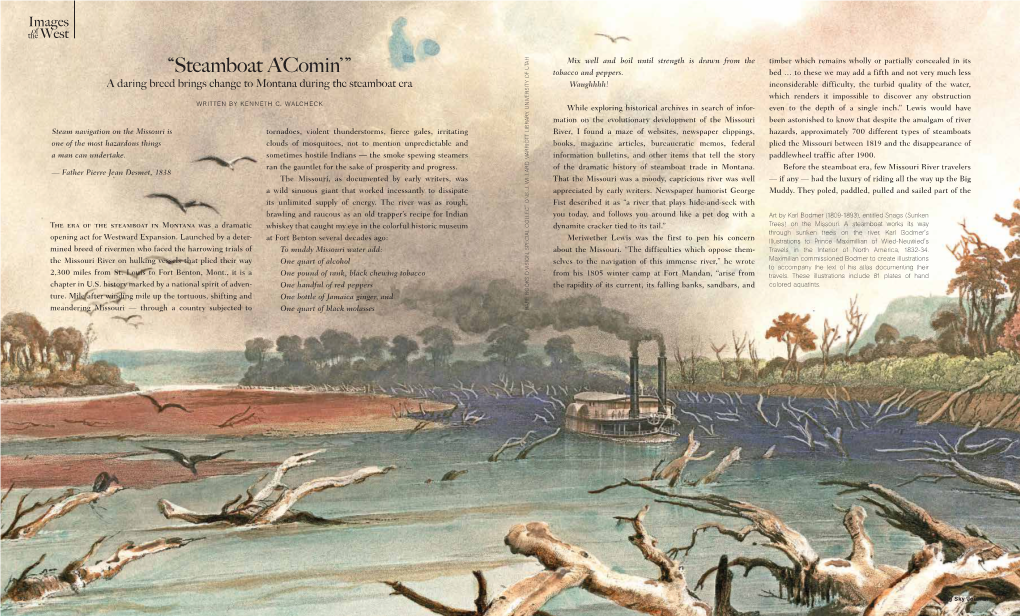

“Steamboat A'comin' ”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dakota Collector April 2006

Dakota Collector A Research Journal of North and South Dakota Postal History Published by the Dakota Postal History Society Vol XXIII Number II April 2006 Fort Rice, Dak.. With “Steamer Waverly MO. Packet” Handstamp EDITORIAL COMMENTS: FROM THE PRESIDENT This issue contains an article I have envisioned for many years, worked on for about six months (on and off), and finally completed in the past weeks….on the subject of the steamboat postal history of Dakota Territory. I would like to thank Mike Ellingson for his support in editing the article and writing most of the Red River sec- tion. Floyd Risvold is also to be recognized for his contribution of a significant number of copies of covers used throughout the article. I hope you all enjoy it! I would also like to direct our membership to an advertisement in this issue from the Western Cover Society. The WCS has scanned in all 55 years of their publication Western Express in text searchable PDF format and put them all onto one DVD. The power of this format is incredible. One can easily search on any topic, just as you would do electronically on the internet (without a million hits, though). Searching on “Dakota”, for exam- ple, yields information on the expresses that operated in/out of Dakota, as well as several articles through the years on different facets of Dakota postal history. I highly recommend the DVD! Best of collecting! Ken Stach 15 N. Morning Cloud Circle The Woodlands, TX 77381 [email protected] FROM THE SECRETARY In this issue we have a fine article by Ken Stach with input from Mike Ellingson on “The Steamboat Postal History of Dakota Territory”. -

History of Navigation on the Yellowstone River

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1950 History of navigation on the Yellowstone River John Gordon MacDonald The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation MacDonald, John Gordon, "History of navigation on the Yellowstone River" (1950). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2565. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2565 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORY of NAVIGATION ON THE YELLOWoTGriE RIVER by John G, ^acUonald______ Ë.À., Jamestown College, 1937 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Mas ter of Arts. Montana State University 1950 Approved: Q cxajJL 0. Chaiinmaban of Board of Examiners auaue ocnool UMI Number: EP36086 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Ois8<irtatk>n PuUishing UMI EP36086 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

OUT HERE, WE HAVE a STORY to TELL. This Map Will Lead You on a Historic Journey Following the Movements of Lt

OUT HERE, WE HAVE A STORY TO TELL. This map will lead you on a historic journey following the movements of Lt. Col. Custer and the 7th Calvary during the days, weeks and months leading up to, and immediately following, the renowned Battle of Little Bighorn were filled with skirmishes, political maneuvering and emotional intensity – for both sides. Despite their resounding victory, the Plains Indians’ way of life was drastically, immediately and forever changed. Glendive Stories of great heroism and reticent defeat continue to reverberate through MAKOSHIKA STATE PARK 253 the generations. Yet the mystique remains today. We invite you to follow the Wibaux Trail to The Little Bighorn, to stand where the warriors and the soldiers stood, 94 to feel the prairie sun on your face and to hear their stories in the wind. 34 Miles to Theodore Terry Roosevelt Fallon National Park 87 12 Melstone Ingomar 94 PIROGUE Ismay ISLAND 12 12 Plevna Harlowton 1 Miles City Baker Roundup 12 89 12 59 191 Hysham 12 4 10 2 12 14 13 11 9 3 94 Rosebud Lavina Forsyth 15 332 447 16 R MEDICINE E ER 39 IV ROCKS IV R R 5 E NE U STATE PARK Broadview 87 STO 17 G OW Custer ON L T NORTH DAKOTA YE L 94 6 59 Ekalaka CUSTER GALLATIN NF 18 7 332 R E 191 IV LAKE Colstrip R MONTANA 19 Huntley R 89 Big Timber ELMO E D Billings W 447 O 90 384 8 P CUSTER Reed Point GALLATIN Bozeman Laurel PICTOGRAPH Little Bighorn Battlefield NATIONAL 90 CAVES Hardin 20 447 FOREST Columbus National Monument Ashland Crow 212 Olive Livingston 90 Lame Deer WA Agency RRIO SOUTH DAKOTA R TRA 212 IL 313 Busby -

Some Chapters in the History of Fort Buford

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1942 Some chapters in the history of Fort Buford Levi N. Larsen The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Larsen, Levi N., "Some chapters in the history of Fort Buford" (1942). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3613. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3613 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. soma OBAPTaa# iB 3%% ei8T0R% o f fORg amMMüo by B« A. JmmeatewR Gbllega, Jameetown. g* D*k# 1932 fr##ebt#6 la partial fnlfillmant of the req&lremeat for the degree of lee- ter of Arts* Moat&n* Stet# University 1 9 4 & Approved; Shsi'rSa' 'o‘f W f’r l’ of E*s#lasrs }f- ^ £ ( Z u i L C X ^ ISimti^n oi uommfftee on Sredmate Rtndy UMI Number; EP36145 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will Indicate the deletion. -

THE CHRIST CHURCH CONNECTION the Newspaper of the Mother Church of the Dakotas

July THE CHRIST CHURCH CONNECTION The Newspaper of the Mother Church of the Dakotas July & August 2021 NEWS FROM PASTOR KWEN SANDERSON The “Good News”(?) of Sin- Romans 3:23- “For all have sinned, and fallen short of the glory of God.” When you translate our language of “Sin”, it is another way of saying, “I am an imperfect human being.” Which gives me permission, that when I have messed up, and made mistakes, their spiritual message is, “Welcome to the Human Race.” When I ministered at the Mike Durfee State Prison in Springfield, the inmates discovered that Romans 3:23 meant that their specific sin, even though it landed them in prison, was a reminder that they were part of the sin of the Human Race. As a colleague liked to remind people, “We are all equal, at the foot of the cross.” In the Friday, June 18, devotion of our “Forward Day by Day” devotional, the author, Keith Gogan, made the insightful observation. “God will act; God will make things better. However, God will not act without us. We humans are both the problem and the solution.” Right from the beginning, with Adam and Eve, how was God going to care for his created world? By Adam and Eve. How did sin enter the world? By Adam and Eve. Yet, It is a continuing theme that runs through the Bible from Genesis to Revelation; God has committed himself to work through people, even though people are the ones who create the problems. In the church, we have a high-sounding doctrine called the Incarnation. -

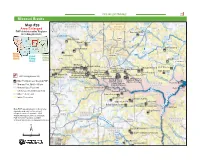

See Map 32 Map

fwp.mt.gov/fishing/ 86 Missouri Breaks s Cr k B P ple ee L A e o A Y R M West Alkali lk N D A a R E N Reservoir l E B L A I N E Y i L Y FORT BELKNAP D I B L A I N E O L O ") C V 66 SON RD L JOHN I O Putnam D D S U r Map # L Y e R 39 O N E C O U N T Y e D C O U N T Y Lake INDIAN k N G Wild Horse V T E RUDOLPH A N R R G R L E D A Reservoir D D L B T Area Enlarged D L E S R RESERVATION i K Y t R M R t R E FWP Administrative Regions Maddux le D D G Ester Lake DNRC N D P L I E eo & Fishing Districts R R p O C L R A le O ow Creek E K s M B E Nelson M SE C I VEN Reservoir T TE EN r Lodge Kalispell Lake RD e L LODG Ridge Reservoir e E PO 6 A LE R Glasgow Seventeen k D Pole G B O I Beaver Creek 1 4 L R D T E Gazob Reservoir SU Great N E N V R P A EA R Falls L MONUMENT PEAK RD Cre UX Whitcomb A Missoula L m e k RD IR E B r Lake IE Helena Y E L a R 7 Hays it D A tl W 2 R V e Miles D N ST E Pr-18 Reservoir SIO R Billings Butch Reservoir MIS D F D D Bozeman 5 R C R City K l R R O R a F A r E RD N E t C e IDG D TIM R E Veseth N e BER I K N REGINA W RD k 3 G R Reservoir O E D Zortman D M R R E Western BEA D T R GULCH R N S First Creek Eastern Fr Reservoir Landusky E T RD E T E Fishing V Central Reservoir L B L C N E E U L O E G L N L Shed Fishing L H A C Leroy K Z R District Fishing W C M Y HACK A ERR IT J Lake M King Reservoir C I P D L D M r ID E District e B H R A R D e L District e R E Sun Prairie D a D k u R con D e ch S d C re am re C ek Gist Ranch e h p Cre k p Cow Island Landing e a F DRY k r FORK RD Pr-20 Reservoir O John Ervin Homestead DY -

The Case for a Custer Battalion Survivor: Private Gustave Korn's Story

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive All Faculty Publications 2013 The aC se for a Custer Battalion Survivor: Private Gustave Korn's Story Albert Winkler Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Original Publication Citation Winkler, A. (2013). The case for a Custer Battalion survivor: Private Gustave Korn’s story. Montana: The aM gazine of Western History, 63(1), 45-55, 94-95. BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Winkler, Albert, "The asC e for a Custer Battalion Survivor: Private Gustave Korn's Story" (2013). All Faculty Publications. 1854. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/1854 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Case for a Custer Battalion Survivor PRIVATE GusTAVE KoRN's STORY by Albert Winkler While nearly all of the accounts of men who claimed to be survivors from Custer's column at the Battle of the Little Bighorn are fictitious, Gustave Korn's story is supported by contemporary records. Korn was one of the troopers who later cared for Captain Miles Keogh's Comanche, the famous horse found alive after the battle. Korn and Comanche are pictured here at Fort Abraham Lincoln in June 1877. 45 NE OF THE MOST intriguing aspects of the Battle of the Little Bighorn is the mys tery Osurrounding George Armstrong Custer's battalion and the five companies m it. -

A Turbulent Upriver Flow: Steamboat Narratives

A TURBULENT UPRIVER FLOW: STEAMBOAT NARRATIVES OF NATURE, TECHNOLOGY, AND HUMANS IN MONTANA TERRITORY by Evan Graham Kelly A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana November 2019 ©COPYRIGHT by Evan Graham Kelly 2019 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The work of this master’s thesis would not have been possible without the assistance and mentorship of the faculty in Montana State University’s Department of History and Philosophy. I am extremely grateful for the indispensable advice, comments, and motivation provided by my committee chair, Dr. Mark Fiege. This project has grown and thrived with his insightful and thoughtful critiques. I am also deeply indebted to my committee members Dr. Brett Walker and Dr. Michael Reidy, both of whom have been incredibly supportive and encouraging of this research project since its inception. Beyond my committee, the advice and knowledge offered by the faculty of MSU’s History and Philosophy Department has been overwhelming and I would like to specifically thank the professors I have worked with during my graduate studies, including: Dr. Billy Smith, Dr. Timothy LeCain, Dr. James Meyer and Dr. Susan Cohen. I would also like to offer my gratitude to other members of the MSU faculty with whom I have interacted and learned from, specifically Dr. Mary Murphy, Dr. Janet Ore, Dr. Maggie Greene, Dr. Amanda Hendrix-Komoto, Dr. Mathew Herman, Dr. Catherine Dunlop, Dr. Robert Rydell, and Professor Dale -

Steamboats on the Missouri River

A BRIEF HISTORY OF STEAMBOATING ON THE MISSOURI RIVER WITH AN EMPHASIS ON THE BOONSLICK REGION by Robert L. Dyer From the BOONE'S LICK HERITAGE Volume 5, No. 2, June 1997 Boonslick Historical Society's Quarterly Magazine Boonslick Historical Society P.O. Box 324 Boonville, MO 65233 Just because the Mississippi is the biggest river in the country, you mustn't get the idea that she's the best and the boats on her the finest and her boatmen the smartest. That ain't true. Son, real steamboatin' begins a few miles north there, where the Missouri and the Mississippi join up. It takes a real man to be a Missouri River pilot, and that's why a good one draws down as high as a thousand dollars a month. If a Mississippi boat makes a good trip to New Orleans and back, its milk-fed crew think they've turned a trick. Bah! That's creek navigatin'. But from St. Louis to Fort Benton and back; close on to five thousand miles, son, with cottonwood snags waitin' to rip a hole in your bottom and the fastest current there ever was on any river darin' your engines at every bend and with Injuns hidin' in the bushes at the woodyard landings ready to rip the scalp off your head; that's a hair-on-your-chest, he-man trip for you! ...And the Missouri has more history stored up in any one of her ten thousand bends than this puny Mississippi creek can boast from her source to the New Orleans delta. -

Montana Fish & Wildlife Commission Meeting Minutes

Montana Fish & WUdUfe COIDIDI.slon MINUTES Montana Fish and Wildlife Commission Meeling F\VP Headquarters - Helena, MT Steve Bullo~ Governor April 14, 2016 Dan vermillion, Gh.lrm.a Commission Members Prescnt via video: Dan Vennillion-Chainnan. Richard Stuker-Vicc Chainnan, 1!O~1\68 and Gary Wolfe, Helena Headquarters llivingston, M1J' 59047 Richard Kerstein and Matt Tourtlotte via video 4IJ6:.222"()624 Dls1rlCt7 Fish, Wildlife & Parks Staff Present: Jeff Hagencr, Director and FWP Staff. Gary'J , Wolre Guests: April 14, 2016 • Sec Commission file folder for sign-in sheet. 4q22 Aspen Drive Missoula, MT 59802 Topics of Discussion: 406-493-9189 I. Call to Order and Pledge of Allegiance District I 2. Approval of 1\'1inutes of the l\'loTch 10,2016 Commission Meeting 3. Approval of Commission Expenses 4. Commission Reports Rlebard'Stuker 5. Director's Report IISS Biilot'Roail 6. Land Reconciliation - Endorsement Chi1rook, Mt 59523 7. Cedar Creek Permanent Change to Instream Flo,,: - Final 406-357-3495 S. Hondkerchlef Lake Harvest limit Waiver (RI) - Final District 3 9. Glendive Chamber of Commerce & Agriculture Paddlensh Grant Committee - Final 10. Toston Fishing Access Site Land Disposal (RJ) - Final Richard Kerstelii II. Bridger Bend Fishing Access Site Lease Renewal with MDT - Final Box 685 12. Petition to Restrict Commercial Outfitting on the Lower Boulder River, near Big Timber-Final Scobey, M'll 59263 13. 2016 Mountain Goat Quotas Outside Blennlol Quota Ranges - Proposed 406'.783'11564 14. 2016 Mountoln Lion Quotas - Proposed D.i>tJl¢I4 15. 2016 CSKT Pheasant, Partridge, & \Vaterfowl Regulations - Endorsement 16. 2016 Eorly Season Mlgrotory Bird Regulolions - Final Mattbew Ifourtlotle 17. -

At the Flood

CHAPTER 1 At the Flood igh up in his fl oating tower, Captain Grant Marsh guided the riverboat Far West toward Fort Lincoln, the home of Lieuten- ant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and the U.S. Army’s Seventh Cavalry. This was Marsh’s fi rst trip up the Missouri since the ice and snow had closed the river the previous fall, and Hlike any good pilot he was carefully studying how the waterway had changed. Every year, the Missouri—at almost three thousand miles the lon- gest river in the United States—reinvented itself. Swollen by spring rain and snowmelt, the Missouri wriggled and squirmed like an overloaded fi re hose, blasting away tons of bottomland and, with it, grove after grove of cottonwood trees. By May, the river was studded with partially sunken cottonwoods, their sodden root-balls planted fi rmly in the mud, their water-laved trunks angled downriver like spears. Nothing could punch a hole in the bottom of a wooden steamboat like the submerged tip of a cottonwood tree. Whereas the average life span of a seagoing vessel was twenty years, a Missouri riverboat was lucky to last fi ve. Rivers were the arteries, veins, and capillaries of the northern plains, the lifelines upon which all living things depended. Rivers determined 1 0001-470_PGI_Last_Stand.indd01-470_PGI_Last_Stand.indd 1 33/4/10/4/10 110:37:400:37:40 AMAM 2 · THE LAST STAND · the annual migration route of the buffalo herds, and it was the buf- falo that governed the seasonal movements of the Indians. -

31762101682753.Pdf (4.831Mb)

History of navigation on the Yellowstone river by John G MacDonald Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Montana State University © Copyright by John G MacDonald (1950) Abstract: no abstract found in this volume Z HISTOEY of EAVIOATIOH OE THE YELLOWSTOHE EIVEB JoHn 0. MacEonald This copy made "by the Department of History at Montana State College with the consent of the author. Any use made of this thesis should also give credit to the author and to Montana State University. WV HISTORY OF NAVIGATION ON THE YELLOWSTONE RIVER by _______ John G . MacDonald_____ B.A., Jamestown College, 1937 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Montana State University 1950 Approved: Chairman of Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School 131444 c/ TABLE OP COHTMTS CHAPTER I. IHTROBHCTIOH I Purpose I General description of the Yellowstone Valley 2 Use of the river "by the Indians 6 II. EARLY EXPLORERS AHB FGR TRADERS OH THE YELLOWSTOHE 10 La Verendrye 10 LeRaye 12 Larocque 13 Lewis and Clark Expedition 14 J ohn Goiter 22 Manuel Lisa 25 Larpenteur 43 Port Sarpy 45' III. EXPLORIHG EXPEBITIOHS AHB FLATBOATIHG OH THE YELLOWSTOHE 51 Gore Expedition 52 Raynolds-Maynadier Expedition 53 Yellowstone Expedition of 1863 56 Hosmer trip to the States, 1865 58 Port Pease 65 iii CHAPTER PAGE ■' Bond’s flat "boating trip, 1877 • 70 IV. STEAMBOATING ON THE YELLOWSTONE ■ ■ 75 Early Missouri River steamboats 76 First steamboats on the Yellowstone 82 Forsyth exploration, 1873 86 Stanley survey, 1873 89 Forsyth and Grant expedition, 1875 94 Military supply, 1876 99 Military and civilian freighting, 1877 111 Military and civilian freighting, 1878-81 120 V.