Museum and Gallery Inset: Teachers' Attitudes and Priorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walk and Cycleroute

Wandsworth N Bridge Road 44 TToo WaterlooWaterloo Good Cycling Code Way Wandsworth River Wandle On all routes… Swandon Town Walk and Cycle Route The Thames Please be courteous! Always cycle with respect Thames Road 37 39 87 www.wandletrail.org Cycle Route Ferrier Street Fairfield Street for others, whether other cyclists, pedestrians, NCN Route 4 Old York 156 170 337 Enterprise Way Causeway people in wheelchairs, horse riders or drivers, to Richmond Ram St. P and acknowledge those who give way to you. Osiers RoadWandsworth EastWWandsworth Hillandsworth Plain Wandle Trail Wandle Trail Connection Proposed Borough Links to the Toilets Disabled Toilet Parking Public Public Refreshments Seating Tram Stop Street MMuseumuseum for Walkers for Walkers to the Trail Future Route Boundary London Cycling Telephone House On shared paths… High Garratt & Cyclists Network Key to map ●Give way to pedestrians, giving them plenty Armoury Way 28 220 270 of room 220 270 B Neville u Lane WANDLE PARK TO PLOUGH LANE MERTON ABBEY MILLS TO MORDEN HALL PARK TO MERTON Wandsworth c ❿ ❾ ❽ ●Keep to your side of the dividing line, k Gill 44 270 h (1.56km, 21 mins) WANDLE PARK (Merton) ABBEY MILLS (1.76km, 25 mins) Close Road ❿ ❾ if appropriate ol d R (0.78km, 11 mins) 37 170 o Mapleton along Bygrove Road, cross the bridge over the Follow the avenue of trees through the park. Cross ●Be prepared to slow down or stop if necessary ad P King Garratt Lane river, along the path. When you reach the next When you reach Merantun Way cross at the the bridge over the main river channel. -

Education Annual Report 1999-2000

Victoria and Albert Museum EDUCATION DEPARTMENT ANNUAL REPORT 1999/2000 EDUCATION DEPARTMENT ANNUAL REPORT 1 APRIL 1999 - 31 MARCH 2000 CONTENTS 1. Summary 2. Introduction 3. Booked programmes Introduction Programmes for schools and teachers Adult academic and general programmes South Asian programmes Chinese programmes Programmes for young people Programmes for visitors with disabilities 4. Unbooked programmes and services Introduction Talks and tours Drop-in workshops and demonstrations Major drop-in events Family programme Gallery resources Gallery and exhibition development 5. Outreach programmes Introduction Shamiana: the Mughal tent South Asian outreach Chinese outreach Young people's outreach Other outreach 6. Public booking and information services Introduction Self-guided visits Lunch Room Gallery bookings Exhibitions Box Office Information and advisory service 7. Services for the museum sector Introduction Government Museum sector Museology cour ses Other courses Other institutions and people 8. Research and development Introduction Research and evaluation 9. Services to the Museum Introduction Room booking Improvement of facilities Other booking services for the Museum Audio-visual services Resources Centre Training of staff Guides and staff Editorial 10. Staff Introduction Administration Adult and Community Education Section Gallery Education Section Formal Education Section 11. Financial development Appendices 1 Publications 2 Professional lectures and conference papers 3 Audience research reports 4 Other professional activity 5 Staff 1. SUMMARY 1.1. Introduction. This report builds on those of recent years and includes data for the previous two years for comparison. 1.2. The year was one of intense activity with the development of the Learning Strategy - Creative Connections; increased reporting in relation to the Funding Agreement with DCMS; major initiatives attracting new audiences, as in the temporary exhibition The Arts of the Sikh Kingdoms; and the management and development of core programmes. -

Newsletter Issue 71

National Museum Directors’ Conference newsletter Issue 71 Contents August 2007 NMDC News .....................................................................................................1 NMDC Seminar on Identity, Diversity and Citizenship: Lessons for our National Museums ................................... 1 NMDC Submission to Conservative Arts Taskforce........................................................................................... 1 Members’ News.................................................................................................1 National Maritime Museum Director Appointed.............................................................................................. 1 New Science Museum Director........................................................................................................................... 1 The National Archives and Microsoft Join Forces to Preserve UK Digital Heritage..................................... 2 Lord Browne and Monisha Shah appointed Tate Trustees............................................................................. 2 Your Tate Track....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Rehang at Tate Liverpool..................................................................................................................................... 2 Inspired - The Science Museum at Swindon..................................................................................................... -

The Clapham Society Newsletter

The Clapham Society Newsletter Issue 338 June 2011 Our regular monthly meetings are held at Clapham Manor Primary School, Belmont Road, SW4 0BZ. The entrance to the school in Brixton Windmill reopens Stonhouse Street, through the new building, is NOT open for On 2 May a colourful procession of over 200 people, our evening meetings. Use the Belmont Road entrance, cross the many in costume, marched up Brixton Hill from playground and enter the building on the right. The hall is open from Windrush Square. Was this a political demonstration or 7.30 pm when coffee and tea are normally available. The talk begins a quaint traditional May Day ceremony? It was neither. promptly at 8 pm and most meetings finish by 9.30 pm. People of all ages had come to celebrate the reopening of Brixton Windmill, restored to its former glory with the Wednesday 15 June shiny black tower glistening in the afternoon sun. Seven Clapham Portraits. Members of the Clapham Society Local History months of intense work had seen the brickwork repaired, Sub-committee will give short illustrated biographies of some interesting strengthened and repainted. The weather-boarded cap former Clapham residents. Peter Jefferson Smith will talk about the had been renewed, the four sails put back and two of Revd. Henry Whitehead (1825-1896), a curate at Holy Trinity Church, them now had shutters to catch the wind. Soon it is Clapham, who found the evidence to prove Dr John Snow’s belief that hoped that the first flour will be ground since the mill cholera was transmitted by infected water. -

The Bulletin the Bulletin

The amenity society for THE BULLETIN Putney & Roehampton December 2010 Season’s Greetings and Happy New Year to all our members from Anthony Marshall & Carolyn McMillan (President & Chair) and all other officers of the Putney Society; we hope you have an enjoyable festive season. May we all return to the fray in 2011 with renewed energy to continue the Society’s work to make Putney & Roehampton better places to live. Members’ Meetings chance to ask Ken any questions they might have Tuesday 30 th Nov. 7.30 pm, Brewer Building about the exhibits and its collections. Members of the Friends of Wandsworth Museum will also be ‘Putney at the Crossroads’ present to speak about their activities in support of Martin Howell , Group Planner in the Council’s the Museum. The Museum is always on the look- Planning Service, will speak about the progress of, out for volunteers. Capacity will be restricted to 50 and consultation on, the LDF (Local Development people, so please let Jonathan Callaway know in Framework), followed by a Q&A session. For full advance if you wish to attend: details, see the November Bulletin. email: [email protected] Thursday 27 th January 2011 7.30 pm mobile: 07768-907672 Wandsworth Museum, West Hill The beautiful new café in Wandsworth Museum ‘Colour Supplement’ will host our Members’ Meeting on the evening of We hope you enjoy the supplement, which should Thursday 27 th January 2011, starting at 7.30 pm. appeal to members interested in our local history. Ken Barbour , the new Director, will speak about This is, for the moment, a one-off, and we can’t the Museum’s collections, its education services, promise them on a regular basis. -

Wandle Trail

Wandsworth N Bridge Road 44 To Waterloo Good Cycling Code Way Wandsworth Ri andon ve Town On all routes… he Thamesr Wandle Sw Walk and Cycle Route T Thames Please be courteous! Always cycle with respect Road rrier Street CyCyclecle Route Fe 37 39 77A F for others, whether other cyclists, pedestrians, NCN Route 4 airfieldOld York Street 156 170 337 Enterprise Way Causeway people in wheelchairs, horse riders or drivers, to Richmond R am St. P and acknowledge those who give way to you. Osiers RoadWandsworth EastWandsworth Hill Plain Wandle Trail Wandle Trail Connection Proposed Borough Links to the Toilets Disabled Toilet Parking Public Public Refreshments Seating Tram Stop Museum On shared paths… Street for Walkers for Walkers to the Trail Future Route Boundary London Cycling Telephone House High Garr & Cyclists Network Key to map ● Armoury Way Give way to pedestrians, giving them plenty att 28 220 270 of room 220 270 B Neville u Lane ❿ WANDLE PARK TO PLOUGH LANE ❾ MERTON ABBEY MILLS TO ❽ MORDEN HALL PARK TO MERTON Wandsworth c ● Keep to your side of the dividing line, k Gill 44 270 h (1.56km, 21 mins) WANDLE PARK (Merton) ❿ ABBEY MILLS ❾ (1.76km, 25 mins) Close Road if appropriate ol d R (0.78km, 11 mins) 37 170 o Mapleton along Bygrove Road, cross the bridge over the Follow the avenue of trees through the park. Cross ● Be prepared to slow down or stop if necessary ad P King Ga river, along the path. When you reach the next When you reach Merantun Way cross at the the bridge over the main river channel. -

Museum of London Annual Report 2004-05

MUSEUM OF LONDON – ANNUAL REPORT 2004/05 London Inspiring MUSEUM OFLONDON-ANNUALREPORT2004/05 Contents Chairman’s Introduction 02 Directors Review 06 Corporate Mandate 14 Development 20 Commercial Performance 21 People Management 22 Valuing Equality and Diversity 22 Exhibitions 24 Access and Learning 34 Collaborations 38 Information and Communication Technologies 39 Collections 40 Facilities and Asset Management 44 Communications 45 Archaeology 48 Scholarship and Research 51 Publications 53 Finance 56 List of Governors 58 Committee Membership 59 Staff List 60 Harcourt Group Members 63 Donors and Supporters 64 MUSEUM OF LONDON – ANNUAL REPORT 2004/05 01 CHAIRMAN’S INTRODUCTION CHAIRMAN’S INTRODUCTION On behalf of the Board of Governors I am pleased to report that the Museum of London has had another excellent year. On behalf of the Board of Governors I am pleased to report that the Museum of London has had another excellent year. My fellow Governors and I pay tribute to the leadership and support shown by Mr Rupert Hambro, Chairman of the Board of Governors from 1998 to 2005. There were many significant achievements during this period, in particular the refurbishment of galleries at London Wall, the first stage of the major redevelopment of the London Wall site, the opening of the Museum in Docklands and the establishment and opening of the London Archaeological Archive and Research Centre at Mortimer Wheeler House.The first stage of the London Wall site redevelopment included a new entrance, foyer and the Linbury gallery, substantially funded by the Linbury Trust.The Museum is grateful to Lord Sainsbury for his continuing support.There were also some spectacular acquisitions such as the Henry Nelson O’Neil’s paintings purchased with the help of the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Introduction National Art Collections Fund and the V&A Purchase Fund. -

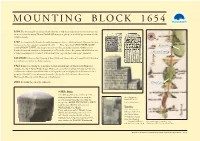

Roehampton Mounting Block Information Board

MOUNTING BLOCK 1654 1654: This mounting block and unofficial milestone, to help horse-riders dismount and remount, was set up at or near this site by Thomas Nuthall of Roehampton, perhaps to mark his appointment as local surveyor of roads. 1787: A passing traveller described it, with drawings, in a letter to The Gentleman’s Magazine (the first known record of it), signed anonymously J.L. of D____, Kent. Apart from MYLS THREE SCORE Richmond Park from LONDON TOWNE, the inscriptions, most now lost, are largely enigmatic. Ogilby had two London-Portsmouth distances: a ‘dimensuration’ of 73½ miles, close to the present official distance, and 9 miles from Cornhill a ‘vulgar computation’ of 60 miles. J.L. wrote that it was “opposite the 9-mile stone.” (see below) 1814/1821: Mentioned by Manning & Bray (1814) and Thomas Kitson Cromwell (1821) but then lost, perhaps removed for road improvements. 1921: Rediscovered during the demolition of a barn in Parish Yard, off Wandsworth High Street (opposite the end of Putney Bridge Road). How it came to be there is a mystery. It was identified by local historian and nurseryman Ernest Dixon, who purchased it and displayed it in his nurseries (later garage) on West Hill. It was subsequently moved to the garden of a local house, then stored at Wandsworth Museum and the University of Roehampton. 2018: Re-installed at or near its original site. Tibbet’s Corner 9-Mile Stone This damaged milestone, at the top of the nearby pedestrian subway, was set up by Above: Inscriptions an 18th century turnpike trust, with the drawn by J.L. -

Brightside December 2014

The magazine of Wandsworth Council Issue 170 December 2014 Wandsworth Employment Christmas event one-way proposals focus round up See page 5 See page 12 See page 20 Delivered to 140,000 homes - Balham Battersea Earlsfield Furzedown Putney Roehampton Southfields Tooting Wandsworth merton.gov.uk/superkids 2 BrightSide wandsworth.gov.uk/brightside www.wandsworth.gov.uk Inside Battersea gets the Tube December 2014 news Join our new residents’ panel 4 Civic Award winners 4 Wandsworth one-way could be scrapped 5 Litter crackdown 6-7 Have your say on airport expansion 10 Wandsworth jobs package 12-13 Crossrail 2 16 Protection for pubs 17 Keep warm this winter 18 Shop local this Christmas 20 Inside Wandsworth Prison Museum 22-23 Remembering heroes 30 regulars What’s On 27 Useful numbers 31 Cover: London Underground comes to Battersea To obtain a copy of Brightside in large print or audio version please telephone (020) 8871 7266 ”The Tube is coming to Battersea! After years of lobbying and hard work by the council the Government has now confirmed or email brightside this incredibly important project has been given the green light. @wandsworth.gov.uk The tunnelling begins next year and the first underground trains YOUR BRIGHTSIDE Your Brightside is distributed by London Letterbox will roll beneath the streets of SW8 in 2020. Marketing. We expect all copies of Brightside to be delivered to every home in the borough and pushed fully The campaign for this privately funded extension of the Northern Line began many years through the letterbox. This issue of Brightside is being ago right here on the pages of Brightside Magazine. -

No 336, April 2011

The Clapham Society Newsletter Issue 336 April 2011 A VISIT TO WANDSWORTH MUSEUM Camping on Clapham Common? Lambeth Council have lifted their self-imposed restrictions on Wednesday 20 April the size, length and frequency of events on Clapham Common. This meeting will be at Wandsworth Museum, 38 West The impact of this change in policy is about to be felt. Hill, SW18 1RZ. The 37 bus goes direct from Clapham The first event, which is causing great concern locally, is Common to Wandsworth Museum. Routes 337 and 170 scheduled to take place from 28 April to 1 May. This will involve from Clapham Junction also go past the Museum. There is a screening of the royal wedding and ‘family’ events. There free parking in nearby streets after 6.30 pm. Admission to will be a campsite with 1800 tents to accommodate up to 4000 the museum is FREE on this evening. people, and food outlets on site. For full details of the event go to www.camproyale.co,uk. Surprisingly, there was no consultation The Museum café, which sells delicious cakes and snacks as about this event with either the Clapham Common Management well as coffee, tea, soft drinks and wine will be open from Advisory Committee (CCMAC) or the Clapham Common Ward 7.30 pm. At 8 pm the Director of the Museum, Ken Barbour, Councillors. will tell us about the history and formation of the museum News of the proposed event led to a Press Statement from and introduce the permanent collection which tells the story Lambeth Council to the effect that final approval had not been of Wandsworth from 25,000 years ago to the present. -

The Mendoza Review: an Independent Review of Museums in England Neil Mendoza

The Mendoza Review: an independent review of museums in England Neil Mendoza November 2017 We can also provide documents to meet the specific requirements for people with disabilities. Please email [email protected] Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport Printed in the UK on recycled paper © Crown copyright 2017 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/ open-government-licence/ or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at [email protected] This document is also available from our website at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-mendoza-review-independent-review-of-museums-in-england The Mendoza Review: an independent review of museums in England 3 Contents Introduction by Neil Mendoza 5 Executive Summary 9 Recommendations: Shaping the Future of Museums 12 A. A joined-up approach from government and its Arm’s Length Bodies 12 B. A clearer museums role for DCMS 13 C. National responsibilities for national museums 14 D. A stronger development function for ACE with museums 14 E. A more effective use of National Lottery funding for museums 15 F. The closer involvement of Historic England 16 Reflections on what the sector can do: 17 What can local authorities do to support thriving museums? 17 Best practice for museums 18 Museums in England Today 19 Public Funding for Museums 21 Understanding and Addressing the Priorities for Museums in England Today 30 I. -

Wandsworth Society Events Wandsworth Society Newsletter September 2015 Restoration of an Artists’ Village a Talk by Perdita Hunt on 7 May 2015

The Ram Brewery on the way to becoming the The Ram Quarter … • Planning news • World Heart Beat Music Academy • An artists’ village • Plaques, ours and another • Underground London • Wandsworth Society events Wandsworth Society Newsletter September 2015 Restoration of an artists’ village A talk by Perdita Hunt on 7 May 2015 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Found_Drowned erdita’s talk to the Society, a Wandsworth a hostel for apprentices. The De Morgans* installed Arts Fringe event, began with an Mary’s kiln. She employed 70 people to decorate introduction to the works of GF Watts a lovely cemetery chapel (the couple were buried P(1817-1904), one of the greatest Victorian nearby), which she designed and built. And she was painters, self-taught by copying pictures at the the first woman to have her designs sold by Liberty’s. National Gallery. Thus came into being at Compton a small ‘artists’ He painted in a wide range of genres, including many village’, according with the couple’s ‘art for all’ portraits – there are notable ones of Lillie Langtry, and vision. Their local activities extended to taking art of Lilian, the orphan whom he and Mary, his second into a prison, with materials supplied to prisoners, wife, adopted. And he sculpted too. One of his most whose work was put on display for sale. famous ‘social’ paintings is “Found Drowned” (above) – the dead body of a woman washed up beneath After both these amazing artists were dead Waterloo Bridge: presumed to have drowned herself to (Mary, much younger than her husband, died in escape the shame of a “fallen woman”, she is depicted 1938), the village sadly decayed, but what joy against a dark industrial cityscape of south London.