Guide to Linux File Command Mastery by Sheryl Calish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief Introduction to Unix-2019-AMS

Brief Intro to Linux/Unix Brief Intro to Unix (contd) A Brief Introduction to o Brief History of Unix o Compilers, Email, Text processing o Basics of a Unix session o Image Processing Linux/Unix – AMS 2019 o The Unix File System Pete Pokrandt o Working with Files and Directories o The vi editor UW-Madison AOS Systems Administrator o Your Environment [email protected] o Common Commands Twitter @PTH1 History of Unix History of Unix History of Unix o Created in 1969 by Kenneth Thompson and Dennis o Today – two main variants, but blended o It’s been around for a long time Ritchie at AT&T o Revised in-house until first public release 1977 o System V (Sun Solaris, SGI, Dec OSF1, AIX, o It was written by computer programmers for o 1977 – UC-Berkeley – Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) linux) computer programmers o 1983 – Sun Workstations produced a Unix Workstation o BSD (Old SunOS, linux, Mac OSX/MacOS) o Case sensitive, mostly lowercase o AT&T unix -> System V abbreviations 1 Basics of a Unix Login Session Basics of a Unix Login Session Basics of a Unix Login Session o The Shell – the command line interface, o Features provided by the shell o Logging in to a unix session where you enter commands, etc n Create an environment that meets your needs n login: username n Some common shells n Write shell scripts (batch files) n password: tImpAw$ n Define command aliases (this Is my password At work $) Bourne Shell (sh) OR n Manipulate command history IHateHaving2changeMypasswordevery3weeks!!! C Shell (csh) n Automatically complete the command -

The Linux Command Line

The Linux Command Line Fifth Internet Edition William Shotts A LinuxCommand.org Book Copyright ©2008-2019, William E. Shotts, Jr. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No De- rivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit the link above or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. A version of this book is also available in printed form, published by No Starch Press. Copies may be purchased wherever fine books are sold. No Starch Press also offers elec- tronic formats for popular e-readers. They can be reached at: https://www.nostarch.com. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds. All other trademarks belong to their respective owners. This book is part of the LinuxCommand.org project, a site for Linux education and advo- cacy devoted to helping users of legacy operating systems migrate into the future. You may contact the LinuxCommand.org project at http://linuxcommand.org. Release History Version Date Description 19.01A January 28, 2019 Fifth Internet Edition (Corrected TOC) 19.01 January 17, 2019 Fifth Internet Edition. 17.10 October 19, 2017 Fourth Internet Edition. 16.07 July 28, 2016 Third Internet Edition. 13.07 July 6, 2013 Second Internet Edition. 09.12 December 14, 2009 First Internet Edition. Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................xvi Why Use the Command Line?......................................................................................xvi -

Unix Security Overview: 1

CIS/CSE 643: Computer Security (Syracuse University) Unix Security Overview: 1 Unix Security Overview 1 User and Group • Users – root: super user (uid = 0) – daemon: handle networks. – nobody: owns no files, used as a default user for unprivileged operations. ∗ Web browser can run with this mode. – User needs to log in with a password. The encrypted password is stored in /etc/shadow. – User information is stored in /etc/passwd, the place that was used to store passwords (not anymore). The following is an example of an entry in this file. john:x:30000:40000:John Doe:/home/john:/usr/local/bin/tcsh • Groups – Sometimes, it is more convenient if we can assign permissions to a group of users, i.e. we would like to assign permission based on groups. – A user has a primary group (listed in /etc/passwd), and this is the one associated to the files the user created. – Any user can be a member of multiple groups. – Group member information is stored in /etc/group % groups uid (display the groups that uid belongs to) – For systems that use NIS (Network Information Service), originally called Yellow Page (YP), we can get the group information using the command ypcat. % ypcat group (can display all the groups and their members) 2 File Permissions • File Permissions – The meaning of the permission bits in Unix. ∗ Owner (u), Group (g), and Others (o). ∗ Readable (r), Writable (w), and Executable (x). ∗ Example: -rwxrwxrwx (777) • Permissions on Directories: – r: the directory can be listed. – w: can create/delete a file or a directory within the directory. -

File Security Lock Down Your Data

File Security Lock Down Your Data Brian Reames January 22, 2012 Table of Contents 1.0 Basic Linux Permissions...............................................................................................................4 1.1 Determining Permissions……………………………………………………………………..................... 5 1.2 File Permissions vs. Directory Permissions………………………………………………….............. 6 1.3 Changing Permissions………………………………………………………………………….................... 7 1.3.1 Symbolic Method…………………………………………………………………….................... 8 1.3.2 Octal Method………………………………………………………………………..................... 10 1.3.3 Changing Permissions Graphically……………………………………………….............. 12 1.4 Examples of Unintentional Access…………………………………………………………................. 13 2.0 Setting Default Permissions………………………………………………………………………...................... 15 2.1 Common umask Settings……………………………………………………………………....................17 3.0 Advanced Linux Permissions……………………………………………………………………….................... 18 3.1 Special Permission: setuid………………………………………………………………….....................19 3.1.1 Setting the setuid Permission……………………………………………………................ 20 3.1.2 Caution Regarding setuid………………………………………………………….................22 3.2 Special Permission setgid……………………………………………………………………................... 23 3.2.1 setgid on a File……………………………………………………………………...................... 24 3.2.2 setgid on a Directory……………………………………………………………….................. 25 3.2.3 Caution Regarding setgid…………………………………………………………................. 28 3.3 Special Permission: sticky bit……………………………………………………………….................. -

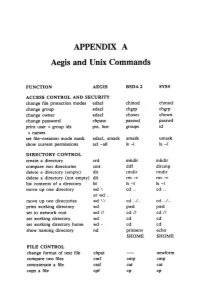

APPENDIX a Aegis and Unix Commands

APPENDIX A Aegis and Unix Commands FUNCTION AEGIS BSD4.2 SYSS ACCESS CONTROL AND SECURITY change file protection modes edacl chmod chmod change group edacl chgrp chgrp change owner edacl chown chown change password chpass passwd passwd print user + group ids pst, lusr groups id +names set file-creation mode mask edacl, umask umask umask show current permissions acl -all Is -I Is -I DIRECTORY CONTROL create a directory crd mkdir mkdir compare two directories cmt diff dircmp delete a directory (empty) dlt rmdir rmdir delete a directory (not empty) dlt rm -r rm -r list contents of a directory ld Is -I Is -I move up one directory wd \ cd .. cd .. or wd .. move up two directories wd \\ cd . ./ .. cd . ./ .. print working directory wd pwd pwd set to network root wd II cd II cd II set working directory wd cd cd set working directory home wd- cd cd show naming directory nd printenv echo $HOME $HOME FILE CONTROL change format of text file chpat newform compare two files emf cmp cmp concatenate a file catf cat cat copy a file cpf cp cp Using and Administering an Apollo Network 265 copy std input to std output tee tee tee + files create a (symbolic) link crl In -s In -s delete a file dlf rm rm maintain an archive a ref ar ar move a file mvf mv mv dump a file dmpf od od print checksum and block- salvol -a sum sum -count of file rename a file chn mv mv search a file for a pattern fpat grep grep search or reject lines cmsrf comm comm common to 2 sorted files translate characters tic tr tr SHELL SCRIPT TOOLS condition evaluation tools existf test test -

Configuring Your Login Session

SSCC Pub.# 7-9 Last revised: 5/18/99 Configuring Your Login Session When you log into UNIX, you are running a program called a shell. The shell is the program that provides you with the prompt and that submits to the computer commands that you type on the command line. This shell is highly configurable. It has already been partially configured for you, but it is possible to change the way that the shell runs. Many shells run under UNIX. The shell that SSCC users use by default is called the tcsh, pronounced "Tee-Cee-shell", or more simply, the C shell. The C shell can be configured using three files called .login, .cshrc, and .logout, which reside in your home directory. Also, many other programs can be configured using the C shell's configuration files. Below are sample configuration files for the C shell and explanations of the commands contained within these files. As you find commands that you would like to include in your configuration files, use an editor (such as EMACS or nuTPU) to add the lines to your own configuration files. Since the first character of configuration files is a dot ("."), the files are called "dot files". They are also called "hidden files" because you cannot see them when you type the ls command. They can only be listed when using the -a option with the ls command. Other commands may have their own setup files. These files almost always begin with a dot and often end with the letters "rc", which stands for "run commands". -

File Security and Permissions

File Security and Permissions File Permissions (1) u With respect to a particular file, Unix divides the set of all users on a system into three categories: – user vThe owner of the file. – group users vMost of you are in the group 2ndyr vUsed for easier administration of access control. vNormally only the superuser can set up groups. vUsers can be in more than one group. – others vEveryone else. File Permissions (2) u Permissions can be viewed with the ls -l command obelix[1] > ls -l total 1247 -rw------- 1 csnow 1117 Jul 23 15:49 bad.cpp drwx--x--x 2 csnow 2048 Jul 17 10:13 bibd/ drwxr-xr-x 2 csnow 512 Aug 27 23:18 cache/ -rw------- 1 csnow 2081 Jul 23 15:49 tst2.s -rw-r-xr-- 1 csnow 1275 Jul 23 15:49 vecexpr.cpp r read permission -rw-r-xr-- w write permission x execute permission File type - = file d = directory User Group Other l=symbolic link Permissions Permissions Permissions File Permissions (3) u Permissions are changed with the chmod command. u There are two syntaxes you can use: chmod DDD file [file ...] – DDD are 3 octal digits representing bits of protection – rwx rwx rwx can be thought of as 111 111 111 in binary rw- r-- r-- 110 100 100 6 4 4 chmod 644 file File Permissions (4) u chmod [ugoa][+-=][rwx] file [...] – This is the “symbolic” method. – chmod u+rwx file gives the User Read, Write, and eXecute – chmod g+rx file gives the Group Read and eXecute – chmod o-rwx file removes R, W, and X from Others – chmod a+x file gives All eXecute permission – chmod g=r file gives Group Read permission and makes sure it has nothing -

Permissions and Ownership

Getting Started with Linux: Novell’s Guide to CompTIA’s Linux+ Objective 1 Understand User and Group Configuration Files Information on users and groups on a Linux system is kept in the following files: ■ /etc/passwd ■ /etc/shadow ■ /etc/group Whenever possible, you should not modify these files with an editor. Instead, use the Security and Users modules in YaST or the command line tools described in the next objective, “Manage User Accounts and Groups from the Command Line” on 7-12. Modifying these files with an editor can lead to errors (especially in /etc/shadow), such as a user—including the user root—no longer being able to log in. To ensure consistency of these files, you need to understand how to ■ Check /etc/passwd and /etc/shadow ■ Convert Passwords to and from Shadow /etc/passwd The file /etc/passwd stores information for each user. In the past, UNIX and Linux users were handled in a single file: /etc/passwd. The user name, the UID, the home directory, the standard shell, and the encrypted password were all stored in this file. The password was encrypted using the function crypt (man 3 crypt). In principle, the plain text password could not be deciphered from the encrypted password. 7-2 Version 2 Use the Command Line Interface to Administer the System However, there are programs (such as john) that use dictionaries to encrypt various passwords with crypt, and then compare the results with the entries in the file /etc/passwd. With the calculation power of modern computers, simple passwords can be “guessed” within minutes. -

User Accounts User Accounts User Info /Etc/Passwd User Info /Etc

User Accounts Even a single-user workstation (Desktop Computer) uses multiple accounts. Such a computer may have just one user account, but several system accounts help keep the computer running. Accounts enable multiple users to share a single computer without causing each other too much trouble. User Accounts The Users in a Linux system are stored in the /etc/passwd file. If you are on your own VM - somewhere near the bottom you should see yourself and joe. On a brand new install you will see many users listed. Of course if you recall, we only added ourselves and joe. So what are all these other users for? These users are added because we don’t want to give sudo power to all of our programs. So each program installed gets its own user with its own limited permissions. This is a protection for our computer. User Info /etc/passwd Examine the /etc/passwd file using cat or less . Here is what we are seeing: It is colon : separated. So each : denotes a new column. username password The x is just a place-holder. The password is not really in this file User ID (UID) Just like every computer needs a unique ip address, every user needs a unique id. User Info /etc/passwd Group ID (GID) Every user belongs to its own group, with its own group id Comment field This is the Full name, phone number, office number, etc. It is okay if it is blank. Home Directory This is the location of the users home directory - This is how we can know the full path of any users home directory - /home/smorgan vs /home/s/smorgan. -

Freebsd Command Reference

FreeBSD command reference Command structure Each line you type at the Unix shell consists of a command optionally followed by some arguments , e.g. ls -l /etc/passwd | | | cmd arg1 arg2 Almost all commands are just programs in the filesystem, e.g. "ls" is actually /bin/ls. A few are built- in to the shell. All commands and filenames are case-sensitive. Unless told otherwise, the command will run in the "foreground" - that is, you won't be returned to the shell prompt until it has finished. You can press Ctrl + C to terminate it. Colour code command [args...] Command which shows information command [args...] Command which modifies your current session or system settings, but changes will be lost when you exit your shell or reboot command [args...] Command which permanently affects the state of your system Getting out of trouble ^C (Ctrl-C) Terminate the current command ^U (Ctrl-U) Clear to start of line reset Reset terminal settings. If in xterm, try Ctrl+Middle mouse button stty sane and select "Do Full Reset" exit Exit from the shell logout ESC :q! ENTER Quit from vi without saving Finding documentation man cmd Show manual page for command "cmd". If a page with the same man 5 cmd name exists in multiple sections, you can give the section number, man -a cmd or -a to show pages from all sections. man -k str Search for string"str" in the manual index man hier Description of directory structure cd /usr/share/doc; ls Browse system documentation and examples. Note especially cd /usr/share/examples; ls /usr/share/doc/en/books/handbook/index.html cd /usr/local/share/doc; ls Browse package documentation and examples cd /usr/local/share/examples On the web: www.freebsd.org Includes handbook, searchable mailing list archives System status Alt-F1 .. -

Access Control Topics

CIT 480: Securing Computer Systems Access Control Topics 1. Access Control Matrix 2. ACLs and Capabilities 3. Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) 4. Discretionary Access Control (DAC) 5. Examples: UNIX, Windows, Android, SQL 6. Mandatory Access Control (MAC) 7. Hardware Protection Access Control Access control is the selective restriction of access to an information, computational, or physical resource. Access Control is Pervasive Application Middleware Operating System Hardware Access Control is Pervasive 1. Application • Complex, custom security policy. • Ex: Amazon account: wish list, reviews, CC 2. Middleware • Database, system libraries, 3rd party software • Ex: Credit card authorization center 3. Operating System • File ACLs, IPC, Android permissions system, SELinux 4. Hardware • Memory management, hardware device access. Access Control Matrices A table that defines permissions. – Each row of this table is associated with a subject, which is a user, group, or system that can perform actions. – Each column of the table is associated with an object, which is a file, directory, document, device, resource, or any other entity for which we want to define access rights. – Each cell of the table is then filled with the access rights for the associated combination of subject and object. – Access rights can include actions such as reading, writing, copying, executing, deleting, and annotating. – An empty cell means that no access rights are granted. Example Access Control Matrix Access Control Lists (ACLs) An ACL defines, for each object, o, a list, L, called o’s access control list, which enumerates all the subjects that have access rights for o and, for each such subject, s, gives the access rights that s has for object o. -

The Linux Command Line

The Linux Command Line Second Internet Edition William E. Shotts, Jr. A LinuxCommand.org Book Copyright ©2008-2013, William E. Shotts, Jr. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No De- rivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit the link above or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Fran- cisco, California, 94105, USA. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds. All other trademarks belong to their respective owners. This book is part of the LinuxCommand.org project, a site for Linux education and advo- cacy devoted to helping users of legacy operating systems migrate into the future. You may contact the LinuxCommand.org project at http://linuxcommand.org. This book is also available in printed form, published by No Starch Press and may be purchased wherever fine books are sold. No Starch Press also offers this book in elec- tronic formats for most popular e-readers: http://nostarch.com/tlcl.htm Release History Version Date Description 13.07 July 6, 2013 Second Internet Edition. 09.12 December 14, 2009 First Internet Edition. 09.11 November 19, 2009 Fourth draft with almost all reviewer feedback incorporated and edited through chapter 37. 09.10 October 3, 2009 Third draft with revised table formatting, partial application of reviewers feedback and edited through chapter 18. 09.08 August 12, 2009 Second draft incorporating the first editing pass. 09.07 July 18, 2009 Completed first draft. Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................xvi