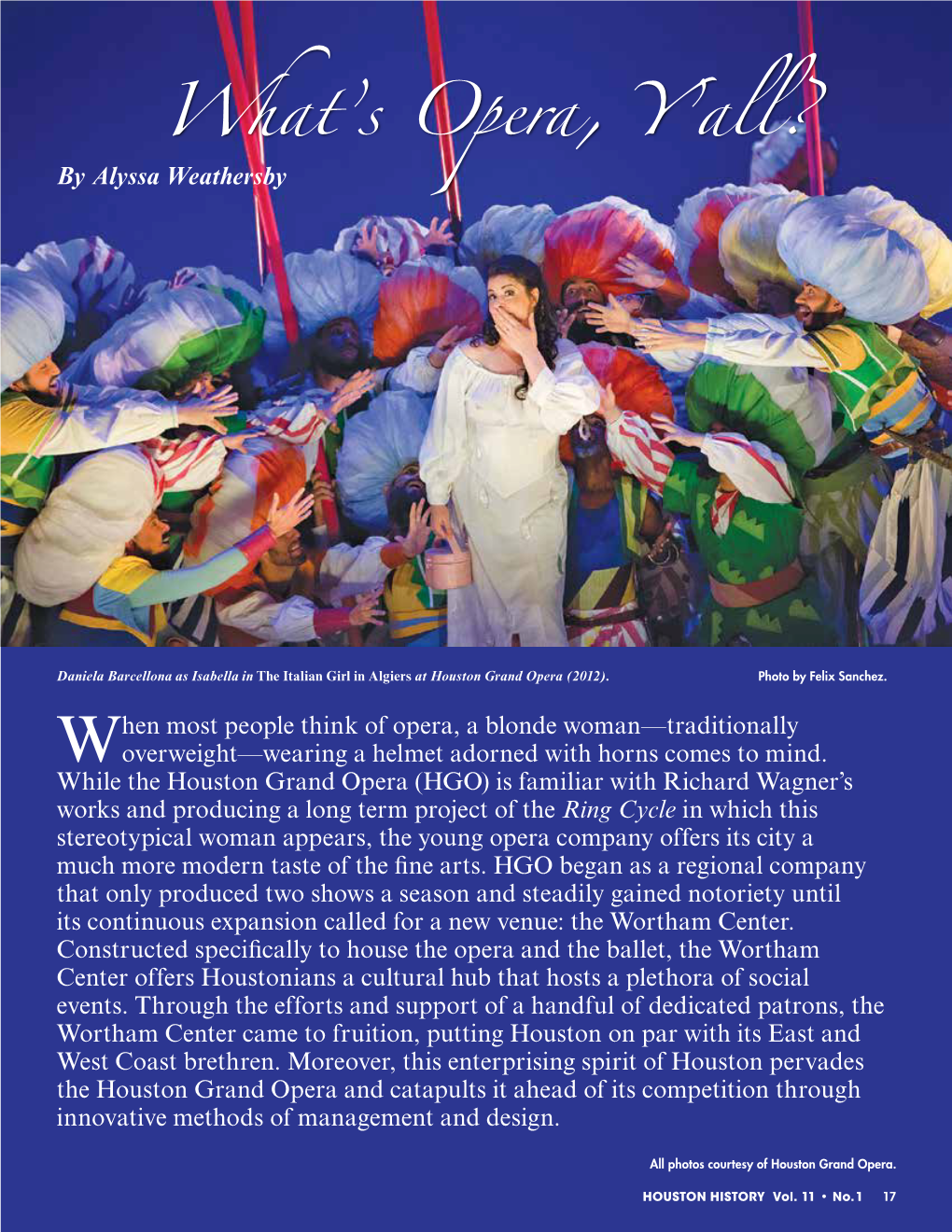

What's Opera, Y'all?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opera Warhorses

Opera Warhorses An appreciation and analysis of the 'Standard Repertory' of opera front page about RSS Recent Posts In Quest of Live Performances of Popular Operas – May-November, 2016 World Premiere Review: “JFK”, a Fort Worth Fantasy – April 23, 2016 Review: Houston Grand Opera’s Convincing Case for “Carousel” – April 22, 2016 Review: Jay Hunter Morris, Christine Goerke Lead a Vocally Strong “Siegfried” Cast – Houston Grand Opera, April 20, 2016 In Quest of European Opera Performances (Part Two) Mid-May 2016 Categories 2005-2016 William's Commentaries (27) 2005-2016: William's Reviews (435) 2008-2016 William's Interviews (86) 50 Year Anniversaries (61) Blazing Batons with Arthur Bloomfield (15) General correspondence (4) Guest Reviews (2) Quests and Anticipations (79) San Francisco Opera DVD Reviews (2) Superlatives (5) Tom's Reviews (42) Tom's Tips (11) William's Conversations (23) William's Conversations with John Pascoe (8) William's Program Notes (6) William's Thoughts and Assessments (12) Archives Archives Select Month ← Review: A Magnificent “Manon” starring Ailyn Pérez and Stephen Costello – The Dallas Opera, March 4, 2016 Review: An Exciting, Moving “Madame Butterfly” – Los Angeles Opera, March 12, 2016 → World Premiere: A Triumphant “Prince of Players” for Composer Carlisle Floyd, Baritone Ben Edquist – Houston Grand Opera, March 5, 2016 March 7th, 2016 Composer Carlisle Floyd, who turns 90 this summer, created the lyrics and music for yet another master work for the Houston Grand Opera, the company in which so much of the Floyd Legacy is invested. The opera, “Prince of Players”, is based considerably on the 2004 movie Stage Beauty. -

Bayou Place Houston, Texas

Bayou Place Houston, Texas Project Type: Commercial/Industrial Case No: C031001 Year: 2001 SUMMARY A rehabilitation of an obsolete convention center into a 160,000-square-foot entertainment complex in the heart of Houston’s theater district. Responding to an international request for proposals (RFP), the developer persevered through development difficulties to create a pioneering, multiuse, pure entertainment destination that has been one of the catalysts for the revitalization of Houston’s entire downtown. FEATURES Rehabilitation of a "white elephant" Cornerstone of a downtown-wide renaissance that has reintroduced nighttime and weekend activity Maximized leasable floor area to accommodate financial pro forma requirements Bayou Place Houston, Texas Project Type: Adaptive Use/Entertainment Volume 31 Number 01 January-March 2001 Case Number: C031001 PROJECT TYPE A rehabilitation of an obsolete convention center into a 160,000-square-foot entertainment complex in the heart of Houston’s theater district. Responding to an international request for proposals (RFP), the developer persevered through development difficulties to create a pioneering, multiuse, pure entertainment destination that has been one of the catalysts for the revitalization of Houston’s entire downtown. SPECIAL FEATURES Rehabilitation of a "white elephant" Cornerstone of a downtown-wide renaissance that has reintroduced nighttime and weekend activity Maximized leasable floor area to accommodate financial pro forma requirements DEVELOPER The Cordish Company 601 East Pratt Street, Sixth Floor Baltimore, Maryland 21202 410-752-5444 www.cordish.com ARCHITECT Gensler 700 Milam Street, Suite 400 Houston, Texas 77002 713-228-8050 www.gensler.com CONTRACTOR Tribble & Stephens 8580 Katy Freeway, Suite 320 Houston, Texas 77024 713-465-8550 www.tribblestephens.com GENERAL DESCRIPTION Bayou Place occupies the shell of the former Albert Thomas Convention Center in downtown Houston’s theater district. -

Coa-Program-For-Web.Pdf

HOUSTON GRAND OPERA AND SID MOORHEAD, CHAIRMAN WELCOME YOU TO THE TAMARA WILSON, LIVESTREAM HOST E. LOREN MEEKER, GUEST JUDGE FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 5, 2021 AT 7 P.M. BROADCAST LIVE FROM THE WORTHAM THEATER CENTER TEXT TO VOTE TEXT TO GIVE Text to vote for the Audience Choice Award. On page Support these remarkable artists who represent 9, you will see a number associated with each finalist. the future of opera. Text the number listed next to the finalist’s name to 713-538-2304 and your vote will be recorded. One Text HGO to 61094 to invest in the next generation vote per phone number will be registered. of soul-stirring inspiration on our stage! 2 WELCOME TO CONCERT OF ARIAS 2021 SID MOORHEAD Chairman A multi-generation Texan, Sid Moorhead is the owner of in HGO’s Overture group and Laureate Society, and he serves Moorhead’s Blueberry Farm, the first commercial blueberry on the company’s Special Events committee. farm in Texas. The farm, which has been in the Moorhead family for three generations, sits on 28 acres in Conroe and Sid was a computer analyst before taking over the family boasts over 9,000 blueberry plants. It is open seasonally, from business and embracing the art of berry farming. He loves to the end of May through mid-July, when people from far and travel—especially to Europe—and has joined the HGO Patrons wide (including many fellow opera-lovers and HGO staffers) visit on trips to Italy and Vienna. to pick berries. “It’s wonderful. -

Watermark W Atermark

WATERMARK A SCHOLARLY JOURNAL PUBLISHED BY THE GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH AT CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, LONG BEACH 8 WATERMARK 8 WATERMARK SPRING 2014 Watermark accepts submissions annually between October and February. We are 8 WWW WWW dedicated to publishing original critical and theoretical essays concerned with literature of all genres and periods, as well as works representing current issues Editor ∙ in the fields of rhetoric and composition. Reviews of current works of literary Mary Sotnick criticism or theory are also welcome. Managing Editors ∙ Rusty Rust Jaime Rapp All submissions must be accompanied by a cover letter that includes the author’s ∙ name, phone number, email address, and the title of the essay or book review. All essay submissions should be approximately 12-15 pages and must be typed American Literature Editors Levon Parseghian ∙ Shouhei J. Tanaka ∙ Amy Desusa in MLA format with a standard 12 pt. font. Book reviews ought to be 750-1,000 words in length. As this journal is intended to provide a forum for emerging British Literature Editors voices, only student work will be considered for publication. Submissions will Bethany Acevedo not be returned. Please direct all questions to [email protected] and address all submissions to: Ethnic American Literature Jaime Rapp ∙ Rusty Rust ∙ Phương Lưu Department of English: Watermark California State University, Long Beach Rhetoric & Composition Editors 1250 Bellflower Boulevard Dya Cangiano Long Beach, CA 90840 Medieval & Renaissance Studies Editors Visit us -

Il Favore Degli Dei (1690): Meta-Opera and Metamorphoses at the Farnese Court

chapter 4 Il favore degli dei (1690): Meta-Opera and Metamorphoses at the Farnese Court Wendy Heller In 1690, Giovanni Maria Crescimbeni (1663–1728) and Gian Vincenzo Gravina (1664–1718), along with several of their literary colleagues, established the Arcadian Academy in Rome. Railing against the excesses of the day, their aim was to restore good taste and classical restraint to poetry, art, and opera. That same year, a mere 460 kilometres away, the Farnese court in Parma offered an entertainment that seemed designed to flout the precepts of these well- intentioned reformers.1 For the marriage of his son Prince Odoardo Farnese (1666–1693) to Dorothea Sofia of Neuberg (1670–1748), Duke Ranuccio II Farnese (1639–1694) spared no expense, capping off the elaborate festivities with what might well be one of the longest operas ever performed: Il favore degli dei, a ‘drama fantastico musicale’ with music by Bernardo Sabadini (d. 1718) and poetry by the prolific Venetian librettist Aurelio Aureli (d. 1718).2 Although Sabadini’s music does not survive, we are left with a host of para- textual materials to tempt the historical imagination. Aureli’s printed libretto, which includes thirteen engravings, provides a vivid sense of a production 1 The object of Crescimbeni’s most virulent condemnation was Giacinto Andrea Cicognini’s Giasone (1649), set by Francesco Cavalli, which Crescimbeni both praised as a most per- fect drama and condemned for bringing about the downfall of the genre. Mario Giovanni Crescimbeni, La bellezza della volgar poesia spiegata in otto dialoghi (Rome: Buagni, 1700), Dialogo iv, pp. -

Availabilities

AVAILABILITIES SOUTH TOWER NORTH TOWER 711 LOUISIANA 700 MILAM FLOOR 32 - 16,605 RSF FLOOR 29 - 21,382 RSF FLOOR 26 - 21,382 RSF FLOOR 21 - 10,715 RSF FLOOR 19 - 7,707 RSF FLOOR 17 - 4,890 RSF FLOOR 16 - 3,890 RSF FLOOR 14 - 8,348 RSF FLOOR 11 - 10,614 RSF FLOOR 12 - 20,407 RSF FLOOR 10 - 20,346 RSF FLOOR 9 - 20,484 RSF FLOOR 11 - 20,407 RSF FLOOR 8 - 20,531 RSF FLOOR 10 - 9,375 RSF FLOOR 7 - 20,429 RSF FLOOR 9 - 20,407 RSF FLOOR 8 - 20,426 RSF FLOOR 7 - 20,442 RSF FLOOR 6 - 20,458 RSF FLOOR 2 - 20,520 RSF LOBBY - 4 Spaces TUNNEL - 3 Spaces SOUTH TOWER NORTH TOWER LARGEST CONTIGUOUS BLOCK LARGEST CONTIGUOUS BLOCK FLOORS 7-10, Pt. 11: 92,404 RSF FLOORS 6-9, Pt. 10: 91,108 RSF PROPERTY FACTS Address 711 Louisianna (South Tower) | 700 Milam (North Tower) Building Class “A” office property, two (2) thirty-six (36) story towers, totaling 1,421,765 RSF Common Area Factor Approximately 15.0% (multi-tenant floors) / 9.0% (single-tenant floors) Floor Size Approximately 21,500 RSF Lease Rate Negotiable Operating Expenses Estimated 2016 Operating Expenses of $16.10 per rentable square foot Lease Term Negotiable Leasehold Improvement Allowance Negotiable Up to 0.3 spaces per 1,000 square feet leased parking available below the building comprised of 525 spaces. Unreserved $220.00 / Reserved $285.00, plus taxes Parking Up to 1.5 spaces per 1,000 square feet lease parking available in Walker @ Main Garage (tunnel access) comprised of 1,000 spaces. -

Bon Appétit!A MUSICAL MONOLOGUE MUSIC by LEE HOIBY TEXT by JULIA CHILD, ADAPTED by MARK SHULGASSER

Bon Appétit!A MUSICAL MONOLOGUE MUSIC BY LEE HOIBY TEXT BY JULIA CHILD, ADAPTED BY MARK SHULGASSER Performed in English 7:30 P.M. CT |NOVEMBER 27 Available on demand through December 26 Bon Appétit! Background Cast Lee Hoiby’s one-woman, one-act opera Bon Julia Child Jamie Barton ‡ Appétit! premiered in 1989 at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, with Jean Stapleton performing the role ‡ Former Houston Grand Opera Studio artist of Julia Child. It was presented as a curtain raiser for Hoiby’s The Italian Lesson, also a musical monodrama. Creative Team The Story Pianist Jonathan Easter* Co-Directors Ryan McKinny ‡ Bon Appétit is a conflation of two episodes of Julia and Tonya McKinny * Child’s cooking show, The French Chef, in which she narrates—with all her wit, antics, and charisma—the * Houston Grand Opera debut baking of the perfect chocolate cake, Le gâteau au ‡ Former Houston Grand Opera Studio artist chocolat l’éminence brune. The entire staff of HGO contributed to the success of this production. For a full listing of the company’s staff, Fun Fact please visit HGO.org/about-us/people. Houston favorite, HGO Studio alumna, and beloved Performing artists, stage directors, and choreog- mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton portrays Child in a role raphers are represented by the American Guild of she has made her own, performing in venues including Musical Artists, the union for opera professionals in New York’s Carnegie Hall. the United States. Underwriters Video and Audio Production Streaming Partner Produced in association Jennifer and Benjamin Fink Keep the Music Going Productions with Austin Opera Bon Appétit! RYAN MCKINNY Richard Tucker Award, both Main and Song Prizes at the BBC Cardiff (United States) Singer of the World Competition, Metropolitan Opera National Council CO-DIRECTOR Auditions, and a Grammy nominee. -

712 & 708 Main Street, Houston

712 & 708 MAIN STREET, HOUSTON 712 & 708 MAIN STREET, HOUSTON KEEP UP WITH THE JONES Introducing The Jones on Main, a storied Houston workspace that marries classic glamour with state-of-the-art style. This dapper icon sets the bar high, with historic character – like classic frescoes and intricate masonry – elevated by contemporary co-working space, hospitality-inspired lounges and a restaurant-lined lobby. Highly accessible and high-energy, The Jones on Main is a stylishly appointed go-getter with charisma that always shines through. This is the place in Houston to meet, mingle, and make modern history – everyone wants to keep up with The Jones. Opposite Image : The Jones on Main, Evening View 3 A Historically Hip Houston Landmark A MODERN MASTERPIECE THE JONES circa 1945 WITH A TIMELESS PERSPECTIVE The Jones on Main’s origins date back to 1927, when 712 Main Street was commissioned by legendary Jesse H. Jones – Houston’s business and philanthropic icon – as the Gulf Oil headquarters. The 37-story masterpiece is widely acclaimed, a City of Houston Landmark recognized on the National Register of Historic Places. Together with 708 Main Street – acquired by Jones in 1908 – the property comprises an entire city block in Downtown Houston. Distinct and vibrant, The Jones touts a rich history, Art Deco architecture, and famous frescoes – soon to be complemented by a suite of one-of-a-kind, hospitality- inspired amenity spaces. Designed for collaboration and social interaction, these historically hip spaces connect to a range of curated first floor retail offerings, replete with brand new storefronts and activated streetscapes. -

And Then One Night… the Making of DEAD MAN WALKING

And Then One Night… The Making of DEAD MAN WALKING Complete program transcript Prologue: Sister Helen and Joe Confession scene. SISTER HELEN I got an invitation to write to somebody on death row and then I walked with him to the electric chair on the night of April the fifth, 1984. And once your boat gets in those waters, then I became a witness. Louisiana TV footage of Sister Helen at Hope House NARRATION: “Dead Man Walking” follows the journey of a Louisiana nun, Sister Helen Prejean, to the heart of the death penalty controversy. We see Sister Helen visiting with prisoners at Angola. NARRATION: Her groundbreaking work with death row inmates inspired her to write a book she called “Dead Man Walking.” Her story inspired a powerful feature film… Clip of the film: Dead Man Walking NARRATION: …and now, an opera…. Clip from the opera “Dead Man Walking” SISTER HELEN I never dreamed I was going to get with death row inmates. I got involved with poor people and then learned there was a direct track from being poor in this country and going to prison and going to death row. NARRATION: As the opera began to take shape, the death penalty debate claimed center stage in the news. Gov. George Ryan, IL: I now favor a moratorium because I have grave concerns about our state’s shameful record of convicting innocent people and putting them on death row. Gov. George W. Bush, TX: I’ve been asked this question a lot ever since Governor Ryan declared a moratorium in Illinois. -

The Journey of Dead Man Walking

Sacred Heart University Review Volume 20 Issue 1 Sacred Heart University Review, Volume XX, Article 1 Numbers 1 & 2, Fall 1999/ Spring 2000 2000 The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking Helen Prejean Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview Recommended Citation Prejean, Helen (2000) "The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking," Sacred Heart University Review: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview/vol20/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the SHU Press Publications at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sacred Heart University Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking Cover Page Footnote This is a lightly edited transcription of the talk delivered by Sister Prejean at Sacred Heart University on October 31, 2000, sponsored by the Hersher Institute for Applied Ethics and by Campus Ministry. This article is available in Sacred Heart University Review: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview/vol20/iss1/1 Prejean: The Journey of Dead Man Walking SISTER HELEN PREJEAN, C.S.J. The Journey of Dead Man Walking I'm glad to be with you. I'm going to bring you with me on a journey, an incredible journey, really. I never thought I was going to get involved in these things, never thought I would accompany people on death row and witness the execution of five human beings, never thought I would be meeting with murder victims' families and accompanying them down the terrible trail of tears and grief and seeking of healing and wholeness, never thought I would encounter politicians, never thought I would be getting on airplanes and coming now for close to fourteen years to talk to people about the death penalty. -

14PL120 Alley Theatre FINAL.Pdf

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department PROTECTED LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: Alley Theatre AGENDA ITEM: C OWNER: Alley Theatre HPO FILE NO.: 14PL120 APPLICANT: Scott J. Atlas DATE ACCEPTED: Aug-21-2014 LOCATION: 615 Texas Avenue HAHC HEARING DATE: Sep-25-2014 SITE INFORMATION Lots 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8 & 12 & Tract 11, Block 60, SSBB, City of Houston, Harris County, Texas. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Protected Landmark Designation HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY The Alley Theatre was founded in 1947 by Nina Vance (1914-1980), one of the most outstanding theatrical directors in the U.S. and Texas in the mid twentieth century. The Alley is now one of the oldest non-profit, professional, resident theater companies in continuous operation in the United States. From its inception, the Alley Theatre staged productions in an “arena” or “in the round” spatial format, a practice associated with cutting-edge theatrical companies in the mid-twentieth-century period. In the Alley’s first season (1947-48), performances were held in a dance studio on Main Street. Audience members had to walk along a narrow outdoor passage to get to the performance space; this passage was the origin of the Alley’s name. In 1962, the Alley Theatre was given a half-block site in the 600 block of Texas Avenue by Houston Endowment and a $2 million grant from the Ford Foundation for a new building and operating expenses. The theater was to be part of a downtown performance and convention complex including Jones Hall, the home of the Houston Symphony, Houston Grand Opera, and Society for the Performing Arts. -

An Interview with Jake Heggie

35 Mediterranean Opera and Ballet Club Culture and Art Magazine A Chat with Composer Jake Heggie Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Othello in the Dansa Âşık Bir Kuğu: Seraglio Meriç Sümen Othello Sarayda FLÜTİST HALİT TURGAY Fotoğraf: Mehmet Çağlarer A Chat with Jake Heggie Composer Jake Heggie (Photo by Art & Clarity). (Photo by Heggie Composer Jake Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Ömer Eğecioğlu Santa Barbara, CA, ABD [email protected] 6 AKOB | NİSAN 2016 San Francisco-based American composer Jake Heggie is the author of upwards of 250 Genç Amerikalı besteci Jake Heggie şimdiye art songs. Some of his work in this genre were recorded by most notable artists of kadar 250’den fazla şarkıya imzasını atmış our time: Renée Fleming, Frederica von Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia bir müzisyen. Üstelik bu şarkılar günümüzün McNair and others. He has also written choral, orchestral and chamber works. But en ünlü ses sanatçıları tarafından yorumlanıp most importantly, Heggie is an opera composer. He is one of the most notable of the kaydedilmiş: Renée Fleming, Frederica von younger generation of American opera composers alongside perhaps Tobias Picker Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia and Ricky Ian Gordon. In fact, Heggie is considered by many to be simply the most McNair bu sanatçıların arasında yer alıyor. Heggie’nin diğer eserleri arasında koro ve successful living American composer. orkestra için çalışmalar ve ayrıca oda müziği parçaları var. Ama kendisi en başta bir opera Heggie’s recognition as an opera composer came in 2000 with Dead Man Walking, bestecisi olarak tanınıyor. Jake Heggie’nin with libretto by Terrence McNally, based on the popular book by Sister Helen Préjean.