Unpacking College Students' Complex Relationships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Plan, a List of Important Kpis, a Line Budget, and a Timeline of the Project

Sierra Marling PRL 725 Come Together Campaign Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 2 Transmittal Letter ................................................................................................................... 3 Background ........................................................................................................................... 4 Situation Analysis .................................................................................................................. 7 Stakeholders .......................................................................................................................... 8 SWOT Analysis ....................................................................................................................... 9 Plan ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Key Performance Indicators ................................................................................................... 17 Budget .................................................................................................................................. 20 Project Timeline (Gantt)......................................................................................................... 21 References ............................................................................................................................ -

United States District Court Southern District of Florida Miami Division

Case 1:15-cv-23888-JEM Document 1 Entered on FLSD Docket 10/16/2015 Page 1 of 25 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA MIAMI DIVISION HUSHHUSH ENTERTAINMENT, INC., a California ) corporation d/b/a Hush Hush Entertainment, Hushpass.com ) and Interracialpass.com, ) ) Case No. Plaintiff, ) v. ) ) MINDGEEK USA, INC., a Delaware corporation, ) d/b/a PORNHUBPREMIUM.COM MINDGEEK USA, ) INC., a Delaware corporation, individually and doing ) business as MINDGEEK USA INC., a Delaware ) corporation, individually and d/b/a ) PORNHUBPREMIUM.COM; MG FREESITES, LTD, ) a Delaware corporation, individually and d/b/a ) PORNHUBPREMIUM.COM; MG BILLING US, a ) Delaware corporation, individually and d/b/a ) PORNHUBPREMIUM.COM; MG BILLING EU, ) a Delaware corporation, individually and d/b/a ) PORNHUBPREMIUM.COM; MG BILLING IRELAND, ) a Delaware corporation, individually and d/b/a ) PORNHUBPREMIUM.COM; LICENSING IP ) INTERNATIONAL S.A.R.L , a foreign corporation ) [DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL] d/b/a PORNHUBPREMIUM.COM; FERAS ANTOON, ) an individual; and DOES 1- 50, ) ) Defendants. ) ________________________________________________) COMPLAINT FOR COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT, DAMAGES, AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF Plaintiff HUSHHUSH ENTERTAINMENT, INC., a California corporation d/b/a Hush Hush Entertainment, Hushpass.com and Interracialpass.com, by and through its attorneys of record, hereby allege as follows: 1 Case 1:15-cv-23888-JEM Document 1 Entered on FLSD Docket 10/16/2015 Page 2 of 25 NATURE OF THE CASE 1. This is an action for violation of Plaintiff, HUSHHUSH ENTERTAINMENT’S intellectual property rights. HUSHHUSH ENTERTAINMENT owns certain adult entertainment content which has been properly registered with the United States Copyright Office. -

Jada Stevens the Hooker Experience Scene 2 Evilangel

1 / 2 Jada Stevens The Hooker Experience, Scene 2 (evilangel) 363 Matches — Huge selection of Jada Stevens pornstar videos ready to watch instantly at Adult Empire. ... This Georgia peach first came on the scene in 2008 when her friend ... Jada is 5' 2" tall and 114 pounds; She has dark brown eyes and hair an. ... In 2014, she won Best Scene in a Vignette for The Hooker Experience at .... May 17, 2014 — Adult Movie Review of The Hooker Experience released by Evil Angel. Written ... STUDIO/PRODUCER: Evil Angel ... SCENE 2 (Jada Stevens):.. The Hooker Experience. ... Category: Gonzo From: Evilangel.com. Date: January 17, 2013. Add to favorites. Related Porn. Jada Stevens Brunette Lesbian Analingus #02, Scene #01/Pornstar ... Jada Stevens Ass Butt Face Two/Pornstar .... Name:Jada.Stevens.The.Hooker.Experience.Scene.2.EvilAngel.2013_iyutero.com.mp4,Hot:5,Created:2017-09-30 14:03:27,Update:2021-05-21 .... AJ Applegate, teen, swallow, Jada Stevens, ass to mouth, evilangel. [07:00] EvilAngel ... [16:00] LESBIAN BUKKAKE 6 Scene 2 ... [01:36] Jada Dee's Very_First Anal Scene ... [31:11] Hookers Experience_Gia DiMarco,Jada_Stevens, India Summer, Maddy O'Reilly ... [25:43] Daisy Marie and Ebony Babe Lesbian Experience.. Evilangel Remy Lacroix Ass Fucking Threesome. Evilangel James Deen In ... Mommy Me And A Black Man Make 3 2 - Scene 2. Adventures Of ... Hookers Experience Gia Dimarco, Jada Stevens, India Summer, Maddy O'reilly. Pov Fuck Jada .... May 16, 2018 — Starring: India Summer, Jada Stevens, Yurizan Beltran, Gia Dimarco, Maddy O'Reilly ... Studio: Evil Angel ... The Hooker Experience, Scene 2 Dirty Panties 2, Belladonna/Evil Angel; Casey Calvert & Jada Stevens .. -

Ised in America, Boasts All Natural 32Dd Breasts!!!! Before Porn, Jade Got a Degree in Art and Did Tattoos at Music Festivals

www.GOLDCLUBCENTERFOLDS.com Join us on the LUNCH GREAT ’18 “gram” FOOD SPECIALS JADE KUSH FEB 20 - FEB 23 WED-SAT @sacnewsreview EXOTIC ASIAN BEAUTY, BORN IN CHINA. RAISED IN AMERICA, BOASTS ALL NATURAL 32DD BREASTS!!!! BEFORE PORN, JADE GOT A DEGREE IN ART AND DID TATTOOS AT MUSIC FESTIVALS. JADE STARRED IN ALMOST 100 XXX MOVIES WITH ALL THE MAJOR STUDIOS INCLUDING BABES.COM, WICKED, EVIL ANGEL, ELEGANT ANGEL, REALITY KINGS, BRAZZERS, NAUGHTY AMERICA, AND MORE!!!! STAGE TIMES: Wednesdays & Thursdays 10:30pm & 12:30am Fridays Noon, 10:00pm, 12:00pm & 2:00am Saturdays 10:00pm, 12:00pm & 2:00am PURE GOLD STORE SIGNING FRI & SAT 6-8PM TOTALLY NUDE SHOWGIRLS ty AMATEUR CONTEST/AUDITIONS DIverSI $5 BEFORE 7PM EVERY MONDAY STORE OPEN 10AM 10:30 PM - $450.00 CASH PRIZE is our FRIENDLY ATTRACTIVE DANCERS CONTRACTED CLUB OPEN 5PM DAILY. CALL 858-0444 FOR SIGN UP INFO alty $5 OFF ADMISSION SpeCI W/AD $5 OFF AFTER 7PM 1 DRINK MINIMUM FREE ADMIT The Only Club w/Ad $5.00 VALUE In Downtown Sacramento VALUE PAK Valid Anytime With Drink Purchase Military Mondays MAGS SUPER SALE w/ Military ID $5 Cover on Mondays Young & FREE Ready 2 PAK $8.99 $5 Off Daily SWANK 2 PAK$8.99 COUPLES With ad, must present ad to receive discount GIrlS DaNCe Cheri 2 PAK $8.99 FaNtaSy aFter Dark party 6pM to Close SEX TOY 4am VOTED 1am- BEST PRICES W/ THIS AD/ONE/PERSON/YEAR Discount not valid during After Dark Party DANCER 5 PACK DVDS BACHELOR / DIVORCE PARTIES CLUB AUDITIONS 916.858.0444 $9.69 FULL SERVICE RESTAURANT W/COUPON REG. -

Three Porn Websites

Case 1:20-cv-00284-CBA-RML Document 1 Filed 01/16/20 Page 1 of 23 PageID #: 1 Mitchell Segal, Esq. MS4878 Law Offices of Mitchell Segal, P.C. 1010 Northern Boulevard, Suite 208 Great Neck, New York 11021 Ph: (516) 415-0100 Fx: (516) 706-6631 Attorneys for Plaintiff and the Class UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ______________________________________________X YAROSLAV SURIS, on behalf of himself and all others similarly situated, Case No.: Plaintiff, CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT -against- MINDGEEK HOLDING SARL d/b/a PORNHUB.COM d/b/a REDTUBE.COM d/b/a YOUPORN.COM, MINDGEEK LOS ANGELES d/b/a PORNHUB.COM d/b/a REDTUBE.COM d/b/a YOUPORN.COM, JOHN DOE CORPS. AND LLC’S 1-100, Defendant, ______________________________________________X 1. Plaintiff, YAROSLAV SURIS (hereinafter "Plaintiff”), on behalf of himself and all others similarly situated, by their attorney, the Law Offices of Mitchell S. Segal, P.C., hereby files this Class Action Complaint against the Defendants, MINDGEEK HOLDING SARL d/b/a PORNHUB.COM d/b/a REDTUBE.COM d/b/a YOUPORN.COM, MINDGEEK LOS ANGELES d/b/a PORNHUB.COM d/b/a REDTUBE.COM d/b/a YOUPORN.COM, JOHN DOE CORPS. AND LLC’S 1-100, (hereinafter "Defendants") and states as follows: 2. The Plaintiff brings this class action for retribution for Defendants actions against deaf and hard of hearing individuals residing in New York and within the United States. Defendants Case 1:20-cv-00284-CBA-RML Document 1 Filed 01/16/20 Page 2 of 23 PageID #: 2 have denied the Plaintiff, who is deaf, and deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals’ access to goods and services provided to non-disabled individuals through its Websites www.pornhub.com as well as its websites www.redtube.com and www.youporn.com (hereinafter the "Websites"), and in conjunction with its physical locations of offices, video studios, advertising offices and hosting locations, is a violation of Plaintiff’s rights under the American with Disabilities Act (“ADA”). -

The Second Digital Disruption: Streaming and the Dawn of Data- Driven Creativity

41816-nyu_94-6 Sheet No. 88 Side A 12/10/2019 14:44:50 \\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\94-6\NYU603.txt unknown Seq: 1 6-DEC-19 15:23 THE SECOND DIGITAL DISRUPTION: STREAMING AND THE DAWN OF DATA- DRIVEN CREATIVITY KAL RAUSTIALA† & CHRISTOPHER JON SPRIGMAN‡ This Article explores how the explosive growth of online streaming is transforming the market for creative content. Two decades ago, the popularization of the internet led to what we refer to here as the first digital disruption: Napster, file-sharing, and the re-ordering of numerous content industries, from music to film to news. The advent of mass streaming has led us to a second digital disruption, one driven by the ability of streaming platforms to harvest massive amounts of data about con- sumer preferences and consumption patterns. Coupled to powerful computing, the data that firms like Netflix, Spotify, and Apple collect allows those firms to know what consumers want in incredible detail. This knowledge has long shaped adver- tising; now it is beginning to shape the content streaming firms purchase or even produce, a phenomenon we call “data-driven creativity.” This Article explores these phenomena across a range of firms and content industries. In particular, we take a close look at the firm that is perhaps farthest along in its use of data-driven crea- tivity. We show how MindGeek, the little-known parent company of Pornhub and a leader in the market for adult entertainment, has leveraged streaming data not only to organize and suggest content to consumers but even to shape creative deci- sions. -

List of All Porno Film Studio in the Word

LIST OF ALL PORNO FILM STUDIO IN THE WORD 007 Erections 18videoz.com 2chickssametime.com 40inchplus.com 1 Distribution 18virginsex.com 2girls1camera.com 40ozbounce.com 1 Pass For All Sites 18WheelerFilms.com 2hotstuds Video 40somethingmag.com 10% Productions 18yearsold.com 2M Filmes 413 Productions 10/9 Productions 1by-day.com 3-Vision 42nd Street Pete VOD 100 Percent Freaky Amateurs 1R Media 3-wayporn.com 4NK8 Studios 1000 Productions 1st Choice 30minutesoftorment.com 4Reel Productions 1000facials.com 1st Showcase Studios 310 XXX 50plusmilfs.com 100livresmouillees.com 1st Strike 360solos.com 60plusmilfs.com 11EEE Productions 21 Naturals 3D Club 666 130 C Street Corporation 21 Sextury 3d Fantasy Film 6666 Productions 18 Carat 21 Sextury Boys 3dxstar.com 69 Distretto Italia 18 Magazine 21eroticanal.21naturals.com 3MD Productions 69 Entertainment 18 Today 21footart.com 3rd Degree 6969 Entertainment 18 West Studios 21naturals.com 3rd World Kink 7Days 1800DialADick.com 21roles.com 3X Film Production 7th Street Video 18AndUpStuds.com 21sextreme.com 3X Studios 80Gays 18eighteen.com 21sextury Network 4 Play Entertainment 818 XXX 18onlygirls.com 21sextury.com 4 You Only Entertainment 8cherry8girl8 18teen 247 Video Inc 4-Play Video 8Teen Boy 8Teen Plus Aardvark Video Absolute Gonzo Acerockwood.com 8teenboy.com Aaron Enterprises Absolute Jewel Acheron Video 8thstreetlatinas.com Aaron Lawrence Entertainment Absolute Video Acid Rain 9190 Xtreme Aaron Star Absolute XXX ACJC Video 97% Amateurs AB Film Abstract Random Productions Action Management 999 -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

Case 2:21-cv-04920 Document 1 Filed 06/17/21 Page 1 of 179 Page ID #:1 Michael J. Bowe David M. Stein (#198256) 1 (pro hac vice application forthcoming) [email protected] [email protected] BROWN RUDNICK LLP 2 Lauren Tabaksblat visa 2211 Michelson Drive, 7th Floor (pro hac vice application forthcoming) Irvine, California 92612 3 [email protected] Telephone: (949) 752-7100 Danielle A. D’Aquila Facsimile: (949) 252-1514 4 (pro hac vice application forthcoming) [email protected] 5 BROWN RUDNICK LLP 7 Times Square 6 New York, NY 10036 Telephone: (212) 209-4800 7 Facsimile: (212) 209-4801 8 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 9 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 SERENA FLEITES and JANE DOE CASE NO. 2:21-cv-4920 11 NOS. 1 through 33, COMPLAINT 12 Plaintiffs, 1. VIOLATIONS OF FEDERAL 13 v. SEX TRAFFICKING LAWS 14 MINDGEEK S.A.R.L. a foreign entity; [18 U.S.C. §§ 1591, 1594, MG FREESITES, LTD., a foreign 1595] 15 entity; MINDGEEK USA 2. RECEIPT, TRANSPORT, INCORPORATED, a Delaware AND DISTRIBUTION OF 16 corporation; MG PREMIUM LTD, a foreign entity; RK HOLDINGS USA CHILD PORNOGRAPHY 17 INC., a Florida corporation, MG [18 U.S.C. §§ 2252, 2252A, GLOBAL ENTERTAINMENT INC., a 2255] 18 Delaware corporation, 3. RACKETEERING TRAFFICJUNKY INC., a foreign [18 U.S.C. §§ 1962] 19 entity; BERND BERGMAIR, a foreign 4. PUBLIC DISCLOSURE OF individual; FERAS ANTOON, a 20 foreign individual; DAVID PRIVATE FACTS TASSILLO, a foreign individual; 5. INTRUSION INTO PRIVATE 21 COREY URMAN, a foreign individual; AFFAIRS VISA INC., a Delaware corporation; 22 COLBECK CAPITAL DOES 1-10; and 6. -

Torrent Cloud Torrentcloud9.Me

Torrent Cloud | TorrentCloud9.me Torrent Cloud Queue Tags SearchSearch All categories Full Length Movies Packs Russian Clips Packs SiteRip's Packs MegaPacks SiteRip's Packs (Gay) Transsexual Title Size Nina Hartley Megapack (480p, 720p and 24.5 GB 1080p)nina.hartley Angel-Desert Megapack 1080p/720ppov 6.2 GB [New Sensations/Digital Sin] The Innocence 24.4 GB of Youth 1-7 & 4 Erotic Stories DVD WMV quality (1024x576p)jenna.j.ross FamilyStrokes.com Siteripfamilystrokes.com 66.3 GB Jasmin St. Claire (biggest bitch in porn) - 57 12.3 GB Clip Anal Megapackblowjob GF Revenge SiteRipdoggy.style 19.2 GB Velicity Von Megapack [170 59.3 GB videos]velicity.von Miko Lee (the asian anal superstar) - 95 Clip 22 GB Anal Megapackasian https://torrentcloud9.me/tag/2590-cum-on-ass/page/1/[28/01/2016 01:49:19] Torrent Cloud | TorrentCloud9.me [GloryHoleLoads] 52 scene siterip [HD] 35.9 GB [Mp4]alina.li PrivateSociety full siterip (53 11.3 GB episodes)threesome Belinha Baracho (Bella, the beach booty 25.8 GB from Brazil) - 69 Clip Anal Megapacktanlines Scarlett Pain MegaPackscarlett.pain 20.5 GB [MyDirtyHobby.com] Annabel-Massina (157 12.6 GB scenes!)anal Tiffany Hopkins (ANAL QUEEN) 28 GB MEGAPACK - There isn't much this bitch WON'T do!anal Babes: SiteRip October 2013 1080p WEB- 19.3 GB DL AAC AVC-TayTOdoggy.style https://torrentcloud9.me/tag/2590-cum-on-ass/page/1/[28/01/2016 01:49:19] Torrent Cloud | TorrentCloud9.me Stracy Stone aka Bijou hardcore sex 5.86 GB video/image megapack [perfect body, nice C cup breasts, and she REALLY enjoys fucking FREELEECH]multiple.cumshots -

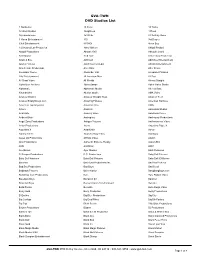

GVA-TWN DVD Studios List

GVA-TWN DVD Studios List 1 Distibution 18 Carat 18 Today 18 West Studios 18eighteen 18Teen 18yearsold.com 1st Strike 21 Sextury Video 3 Vision Entertainment 310 3rd Degree 6969 Entertainment 818XXX 8teen Boy A Lickwood Lab Production Abby Winters Abigail Product Abigail Productions Abolute XXX Absoulte Jewel Acid Digital Acid Rain Active Duty Production Adam & Eve Addicted Addictive Entertainment Adonis Pictures Adult Source Media African Entertainment Afro-Centric Productions After Dark After Shock Alexander Devoe Alexander Inst. Alexander Pictures Alibi Entertainment All American Men All Boy All Great Video All Worlds Almost Straight Alpha Blue Archives Alpha Dawgz Alpha Males Studio Alphamale Alphamale Media Altered State Altomar Men Alusion Studio AMA Video Amateur District Amateur Straight Guys Amateur Teen AmateurStraightGuys.com Amazing Pictures American Hardcore American Top Argentina American Vice AMG Amore Anabolic Anaconda Studios Anal Gate Anarchy Films Anastasia Pierce Andrew Blake Androgeny Androgeny Productions Angel Zone Productions Antigua Pictures AntiInnocence Video Anton Productions Arena Argentina Triple X Argentina X ArrackX69 Arrow Ashley Renee Asian Fantasy Films Asianguy Asses Up Productions ATKOL Video Atomic Aton Productions Authentic Extreme Reality Avalon Ent. AVN AVNS Inc. AWV Axel Braun Ayor Studios B&D Pleasures B. Pumper Productions B.C. Productions Baby Doll Extreme Baby Doll Hardcore Baby Doll Pictures Baby Doll XXXtreme Bacchus Back End Productions Inc. Bad Ass Pictures Bad Boy Productions Bad Boys -

AICO Newsletter

>> NEWSLETTER | ISSUE 21 - NOVEMBER 2012 ABN 70 106 510 ADULT INDUSTRY COPYRIGHT ORGANISATION LIMITED >> AICO CELEBRATES continue to work with you to achieve a level ITS 9TH BIRTHDAY! playing field. Our catch-cry to others remains, Pirates Beware! You can request a copy of AICO’s brochure Congratulations and happy birthday AICO How to spot a pirate DVD via email, info@aico. members and supporters. AICO is now officially org.au or by calling 02 9328 5527. A soft copy nine years old. This is a great achievement for download is available on the home page of the ONGOING Investigation OF an organisation that was greeted with curiosity, >> AICO web site. Adult STORES, Catalogues surprise and a degree of uncertainty, even sus- &WEB SITES picion by some in the adult industry way back in September 2003. The position of those caught selling pirated >> AICO HOLOGRAMS or illegally parallel imported DVDs remains During these nine years AICO has created a perilous. AICO distributor members have affixed over 5.5 climate in the Australian adult film industry million AICO holograms to their films. By that is very piracy aware. In most instances Piracy undermines the livelihood of legitimate purchasing DVDs that display the AICO wholesalers, retailers and the public are keen to film retailers and distributors and remains a real hologram you are assured that the films you respect the film rights of copyright owners and and ongoing threat to the studios, producers, are buying are authentic. their distributors. actors, directors, technicians, marketers and other employees that make adult films possible. Those who have chosen to trade under a pirate flag have felt AICO’s investigative and enforce- Illegitimate operators and adult media pirates ment reach through the courts of Australia and do not want to see an industry with a level via other legal enforcement activity. -

Case 2:11-Cv-09514-PSG-JCG Document 68 Filed 11/15/12 Page 1 of 30 Page ID #:1022 Case 2:11-Cv-09514-PSG-JCG Document 68 Filed 11/15/12 Page 2 of 30 Page ID #:1023

Case 2:11-cv-09514-PSG-JCG Document 68 Filed 11/15/12 Page 1 of 30 Page ID #:1022 Case 2:11-cv-09514-PSG-JCG Document 68 Filed 11/15/12 Page 2 of 30 Page ID #:1023 1 COUNTERCLAIMS 2 Counterclaimant ICM Registry, LLC (“ICM” or “Counterclaimant”) for its 3 counterclaims against Counterdefendants Manwin Licensing International 4 S.A.R.L. (“Manwin”), Digital Playground, Inc. (“Digital Playground”) and Does 5 11-20 (collectively “Counterdefendants”) alleges the following: 6 I. PARTIES AND JURISDICTION 7 1. ICM is informed and believes that Manwin is a Luxembourg limited 8 liability company with its principal place of business in the city of Luxembourg, 9 Luxembourg. 10 2. ICM is informed and believes that Digital Playground is a California 11 corporation with its principal place of business in Van Nuys, California. 12 3. Counterdefendants Manwin and Digital Playground have submitted to 13 the jurisdiction of this Court by commencing their action for antitrust violations in 14 this judicial district, as set forth in the First Amended Complaint (“FAC”). 15 4. ICM is a Delaware limited liability company, with its principal place 16 of business in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida. 17 5. ICM is unaware of the true names or capacities of the 18 counterdefendants sued under the fictitious names Does 11 through 20, inclusive. 19 ICM is informed and believes that Does 11 through 20, and each of them, either 20 participated in performing the acts averred in these counterclaims or were acting as 21 the agent, principal, alter ego, employee, or representative of those who 22 participated in the acts averred in these counterclaims.