War and Peace Ebook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Problems of Mimetic Characterization in Dostoevsky and Tolstoy

Illusion and Instrument: Problems of Mimetic Characterization in Dostoevsky and Tolstoy By Chloe Susan Liebmann Kitzinger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Irina Paperno, Chair Professor Eric Naiman Professor Dorothy J. Hale Spring 2016 Illusion and Instrument: Problems of Mimetic Characterization in Dostoevsky and Tolstoy © 2016 By Chloe Susan Liebmann Kitzinger Abstract Illusion and Instrument: Problems of Mimetic Characterization in Dostoevsky and Tolstoy by Chloe Susan Liebmann Kitzinger Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Irina Paperno, Chair This dissertation focuses new critical attention on a problem central to the history and theory of the novel, but so far remarkably underexplored: the mimetic illusion that realist characters exist independently from the author’s control, and even from the constraints of form itself. How is this illusion of “life” produced? What conditions maintain it, and at what points does it start to falter? My study investigates the character-systems of three Russian realist novels with widely differing narrative structures — Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1865–1869), and Dostoevsky’s The Adolescent (1875) and The Brothers Karamazov (1879–1880) — that offer rich ground for exploring the sources and limits of mimetic illusion. I suggest, moreover, that Tolstoy and Dostoevsky themselves were preoccupied with this question. Their novels take shape around ambitious projects of characterization that carry them toward the edges of the realist tradition, where the novel begins to give way to other forms of art and thought. -

War & Peace by Helen Edmundson

War & Peace by Helen Edmundson from the novel by Leo Tolstoy Education Pack by Gillian King Photo: Alistair Muir | Rehearsal Photography: Ellie Kurttz | Designed by www.stemdesign.co.uk Contents • The Pack........................................................................................... 03 • Shared Experience Expressionism.............................................................. 04 • Summary of War & Peace........................................................................ 05 • Helen Edmundson on the Adaptation Process................................................. 07 • Ideas inspired by the research trip to Russia................................................. 08 • Tolstoy’s Russia.................................................................................... 09 • Leo Tolstoy Biography............................................................................. 10 • Playing the Subtext................................................................................ 12 • What do I Want? (exploring character intentions)............................................ 14 • Napoleon’s 1812 Campaign in Russia........................................................... 17 • The Battle - Created through the Actors’ Physicality......................................... 19 • The Ensemble Process............................................................................ 20 • Russian Women...................................................................................... 22 • Is Man Nothing More Than a Puppet?.......................................................... -

Unpalatable Pleasures: Tolstoy, Food, and Sex

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Scholarship Languages, Literatures, and Cultures 1993 Unpalatable Pleasures: Tolstoy, Food, and Sex Ronald D. LeBlanc University of New Hampshire - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/lang_facpub Recommended Citation Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel. Tolstoy’s Pierre Bezukhov: A Psychoanalytic Study. London: Bristol Classical Press, 1993. Critiques: Brett Cooke, Ronald LeBlanc, Duffield White, James Rice. Reply: Daniel Rancour- Laferriere. Volume VII, 1994, pp. 70-93. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW ~·'T'::'1r"'T,n.1na rp.llHlrIP~ a strict diet. There needs to'be a book about food. L.N. Tolstoy times it seems to me as if the Russian is a sort of lost soul. You want to do and yet you can do nothing. You keep thinking that you start a new life as of tomorrow, that you will start a new diet as of tomorrow, but of the sort happens: by the evening of that 'very same you have gorged yourself so much that you can only blink your eyes and you cannot even move your tongue. N.V. Gogol Russian literature is mentioned, one is likely to think almost instantly of that robust prose writer whose culinary, gastronomic and alimentary obsessions--in his verbal art as well as his own personal life- often reached truly gargantuan proportions. -

Living with Death: the Humanity in Leo Tolstoy's Prose Dr. Patricia A. Burak Yuri Pavlov

Living with Death: The Humanity in Leo Tolstoy’s Prose A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Renée Crown University Honors Program at Syracuse University Liam Owens Candidate for Bachelor of Science in Biology and Renée Crown University Honors Spring 2020 Honors Thesis in Your Major Thesis Advisor: _______________________ Dr. Patricia A. Burak Thesis Reader: _______________________ Yuri Pavlov Honors Director: _______________________ Dr. Danielle Smith, Director Abstract What do we fear so uniquely as our own death? Of what do we know less than the afterlife? Leo Tolstoy was quoted saying: “We can only know that we know nothing. And that is the highest degree of human wisdom.” Knowing nothing completely contradicts the essence of human nature. Although having noted the importance of this unknowing, using the venture of creative fiction, Tolstoy pined ceaselessly for an understanding of the experience of dying. Tolstoy was afraid of death; to him it was an entity which loomed. I believe his early involvements in war, as well as the death of his brother Dmitry, and the demise of his self-imaged major character Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, whom he tirelessly wrote and rewrote—where he dove into the supposed psyche of a dying man—took a toll on the author. Tolstoy took the plight of ending his character’s life seriously, and attempted to do so by upholding his chief concern: the truth. But how can we, as living, breathing human beings, know the truth of death? There is no truth we know of it other than its existence, and this alone is cause enough to scare us into debilitating fits and ungrounded speculation. -

Sample Pages

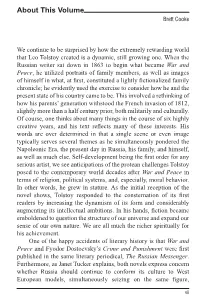

About This Volume Brett Cooke We continue to be surprised by how the extremely rewarding world WKDW/HR7ROVWR\FUHDWHGLVDG\QDPLFVWLOOJURZLQJRQH:KHQWKH Russian writer sat down in 1863 to begin what became War and PeaceKHXWLOL]HGSRUWUDLWVRIfamily members, as well as images RIKLPVHOILQZKDWDW¿UVWFRQVWLWXWHGDOLJKWO\¿FWLRQDOL]HGfamily chronicle; he evidently used the exercise to consider how he and the SUHVHQWVWDWHRIKLVFRXQWU\FDPHWREH7KLVLQYROYHGDUHWKLQNLQJRI KRZKLVSDUHQWV¶JHQHUDWLRQZLWKVWRRGWKH)UHQFKLQYDVLRQRI slightly more than a half century prior, both militarily and culturally. Of course, one thinks about many things in the course of six highly FUHDWLYH \HDUV DQG KLV WH[W UHÀHFWV PDQ\ RI WKHVH LQWHUHVWV +LV words are over determined in that a single scene or even image typically serves several themes as he simultaneously pondered the Napoleonic Era, the present day in Russia, his family, and himself, DVZHOODVPXFKHOVH6HOIGHYHORSPHQWEHLQJWKH¿UVWRUGHUIRUDQ\ VHULRXVDUWLVWZHVHHDQWLFLSDWLRQVRIWKHSURWHDQFKDOOHQJHV7ROVWR\ posed to the contemporary world decades after War and Peace in terms of religion, political systems, and, especially, moral behavior. In other words, he grew in stature. As the initial reception of the QRYHO VKRZV 7ROVWR\ UHVSRQGHG WR WKH FRQVWHUQDWLRQ RI LWV ¿UVW readers by increasing the dynamism of its form and considerably DXJPHQWLQJLWVLQWHOOHFWXDODPELWLRQV,QKLVKDQGV¿FWLRQEHFDPH emboldened to question the structure of our universe and expand our sense of our own nature. We are all much the richer spiritually for his achievement. One of the happy accidents of literary history is that War and Peace and Fyodor 'RVWRHYVN\¶VCrime and PunishmentZHUH¿UVW published in the same literary periodical, The Russian Messenger. )XUWKHUPRUHDV-DQHW7XFNHUH[SODLQVERWKQRYHOVH[SUHVVFRQFHUQ whether Russia should continue to conform its culture to West (XURSHDQ PRGHOV VLPXOWDQHRXVO\ VHL]LQJ RQ WKH VDPH ¿JXUH vii Napoleon Bonaparte, in one case leading a literal invasion of the country, in the other inspiring a premeditated murder. -

A Cold, White Light: the Defamiliarizing Power of Death in Tolstoy‟S War and Peace Jessica Ginocchio a Thesis Submitted To

A Cold, White Light: The Defamiliarizing Power of Death in Tolstoy‟s War and Peace Jessica Ginocchio A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of the Arts in the Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures (Russian). Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Christopher Putney Radislav Lapushin Hana Pichova Abstract JESSICA GINOCCHIO: A Cold, White Light: The Defamiliarizing Power of Death in Lev Tolstoy‟s War and Peace (Under the direction of Christopher Putney) In this thesis, I examine the theme of death in War and Peace by Lev Tolstoy. Death in War and Peace causes changes in characters‟ perception of their own lives, spurring them to live “better.” Tolstoy is widely understood to embed moral lessons in his novels, and, even in his early work, Tolstoy presents an ideal of the right way to live one‟s life. I posit several components of this Tolstoyan ideal from War and Peace and demonstrate that death leads characters toward this “right way” through an analysis of the role of death in the transformations of four major characters—Nikolai, Marya, Andrei, and Pierre. ii Table of Contents Chapter: I. Introduction…………………………………………………………………..1 II. Death in Tolstoy……………………………………………………………....5 III. The Right Way……………………………………………………………….14 IV. War and Peace………………………………………………………………..20 a. Nikolai Rostov ……………………………………………...…………...23 b. Marya Bolkonskaya……………………………………………...………27 c. Andrei Bolkonsky…………………………………………………….….30 d. Pierre Bezukhov………………………………………………………….41 V. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………...53 REFERENCES………………………………………………………………………56 iii Chapter I Introduction American philosopher William James identified Tolstoy as a “sick soul,” a designation he based on Tolstoy‟s obsession with death (James, 120-149). -

THE USE of the FRENCH LANGUAGE in LEO TOLSTOY's NOVEL, WAR and PEACE by OLGA HENRY MICHAEL D. PICONE, COMMITTEE CHAIR ANDREW

THE USE OF THE FRENCH LANGUAGE IN LEO TOLSTOY’S NOVEL, WAR AND PEACE by OLGA HENRY MICHAEL D. PICONE, COMMITTEE CHAIR ANDREW DROZD MARYSIA GALBRAITH A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Modern Languages and Classics in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2016 Copyright Olga Henry 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This study comprises an inventory and an analysis of the types of code-switching and the reasons for code-switching in Leo Tolstoy’s novel, War and Peace. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Russia were marked by multilingualism among the nobility. The French language, in particular, was widely known and used in high society. Indeed, French was considered expressively superior to Russian (Offord, Ryazanova-Clarke, Rjéoutski & Argent, 2015). Then as now, code-switching was a common phenomenon among bilinguals. There were subjects discussed specifically in French, and others in Russian, in Tolstoy’s novel, which represents the life in Russia between 1807 and 1812, and which was constructed to reflect the nature of the time period and its characteristics. In this paper, using the theoretical model proposed by Myers-Scotton (1995) based on markedness, an identification is made of reasons for using code-switching. This is correlated with René Appel and Pieter Muysken’s (1987) five functions of code-switching; and Benjamin Bailey’s (1999) three functional types of switching. A delineation is also made of the types of topics discussed in the French language by the Russian aristocracy, the types of code-switching used most frequently, and the base language of code- switching in Tolstoy’s novel. -

Ravage, Rejection, Regeneration: Leo Tolstoy's <I>War and Peace</I> As a Case Against Forgetting

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2008 Ravage, Rejection, Regeneration: Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace as a Case against Forgetting Irina R. Nersessova Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Recommended Citation Nersessova, Irina R., "Ravage, Rejection, Regeneration: Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace as a Case against Forgetting" (2008). Senior Honors Theses. 176. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/176 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. Ravage, Rejection, Regeneration: Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace as a Case against Forgetting Degree Type Open Access Senior Honors Thesis Department English Language and Literature Keywords Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 1828-1910. VoiÌna i mir Criticism and interpretation, Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 1828-1910 Political and social views, War and civilization, War in literature This open access senior honors thesis is available at DigitalCommons@EMU: http://commons.emich.edu/honors/176 RAVAGE, REJECTION, REGENERATION: LEO TOLSTOY’S WAR AND PEACE AS A CASE AGAINST FORGETTING By Irina R. Nersessova A Senior Thesis Submitted to the Eastern Michigan University Honors College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors in English Language and Literature Approved at Ypsilanti, Michigan, -

How to Read Tolstoy's War and Peace: Antiquity and Equivalence**

Matthias Freise* How to Read Tolstoy’s War and Peace: Antiquity and Equivalence** DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12775/LC.2018.056 In the subtitle of the chapter on War and Peace in his book The Art of History, Christopher Bram promises us to finally explain “how to readWar and Peace, often called the greatest novel ever written” (Bram 2016: 75). However, what follows in his book are well known theses about the unpredictability of fate, observations on Tolstoy’s pace of narration and the dispensability of the second epilogue. Eventually, “the truth of War and Peace” allegedly “lies in the examples of individual men and women trying to find the room to be human inside the dense machinery of history” (ibid.). It offers everything but an instruction for the appropriate reading of truly “the greatest novel ever written”. But is this necessary at all? No scholar has yet recommended a specific reading attitude in order to decode this vast novel, 191 most probably because a “realistic” text does not seem to require special decoding. The flow of history itself seems to provide the narrative line, along which we scrape through these 1600 pages. But why then should it be the greatest novel ever written? Could not every one of us with some talent reproduce such a flow of history? Therefore and nevertheless, the readers ofWar and Peace are in need of some 4(28) 2018 guidance – not only because they might lose orientation in the multitude of scenes, figures, actions and places, but also to be able to grasp the poetic structure of the novel. -

Nathan Rosen, Notes on War and Peace

Notes NOTES ON WAR AND PEACE Nathan Rosen, University of Rochester 1. Tolstoy's Biolo~ism By the end of the First Epilogue Pierre Bezukhov is happily married to Natasha Rostova and they have four children. As a guide to life he has adopted the philosophy of Platon Karataev. Yet he feels that he must take part in the meetings of a secret society in Petersburg that will eventually lead to the Decembrist uprising. Natasha asks Pierre whether Karataev would have approved of their married life. Yes, says Pierre, he would have approved of their family life but not of Pierre's involvement in a secret political society. It is odd that neither Pierre nor Natasha is at all disturbed by the thought that Karataev would have disapproved of Pierre's political ac tivity. Of course Pierre knows, as Tolstoy does, that only unconscious activity bears fruit--yet "at that moment it seemed to him that he was chosen to give a new direction to the whole of Russian society and to the whole world."' In other words, become a Napoleon. This contradiction between Karataev's philosophy and Pierre's action is, according to Bocharov, Tolstoy's "ironic commentary" on what life is like. 2 I think a good deal more could be said about it. Let us consider a similar case--Prince Andrei Bolkonsky after the battle of Austerlitz. Disillusioned in military "glory," driven by guilt over his behavior to his late wife, he decides to retire from the world and concentrate on managing his estate at Bogucharovo and bringing up his son. -

The French Passages of Tolstoy's War and Peace in English Translation

Shedding Light on the Shadows: The French Passages of Tolstoy’s War and Peace in English Translation by Caitlin Towers Timothy Portice, Advisor Julien Weber, Second Reader Comparative Literature Thesis Middlebury College Middlebury, VT February 8, 2016 1 Introduction Lev Tolstoy first published the entirety of his novel War and Peace in 1869.1 It did not take long for his work to reach a foreign audience, and the first translation of War and Peace into English was completed between 1885 and 1886. Over the past century and a half since its publication there have been twelve major English translations of the novel. Archdeacon Farrar, who was a 19th century cleric and author, said “If Count Tolstoï’s books have appeared in edition after edition, and translation after translation, the reason is because the world learns from him to see life as it is” (Dole, iii) Each translation of a novel speaks to a different generation and different audience, and helps decades of readers learn “to see life as it is” in ways specific to their times. With each new translation Tolstoy’s novel becomes accessible to and relatable for new audiences, ranging from a British audience at the turn of the century to an American audience in the middle of the Cold War. Although all of these American and British translations vary in ways that are fascinating culturally, politically and historically, this study focuses specifically on one aspect of the translation of War and Peace: the different ways in which the many passages of the novel originally written in French are translated. -

Tolstoy Syllabus

MSC, FALL 2019, TOLSTOY: WAR AND PEACE (Pevear/Volokhonsky translation, Vintage Classics. Mon 12:30-2:30 George Young. [email protected] 207.256.9112 September 9 Introduction. Tolstoy’s life and time. W&P Volume One, Part One, pp. 3-111 (1805. Anna Scherer’s Soiree. Pierre at Prince Andrei’s. Pierre at Anatole Kuragin’s. Dolokhov’s Bet. Name Day at the Rostovs’. Death of Count Bezukhov. Bald Hills. Old Prince Bolkonsky and Princess Marya Bolkonskaya. Prince Andre’s Departure.) September 16 Volume One, Parts Two and Three. pp. 112-294 (1805. Battle of Schon Graben. Prince Andrei. Nikolai and Denisov. Emperor Alexander. General Kutuzov. Napoleon. Soiree at Anna Scherer’s. Pierre and Helene. Princess Marya, Anatole, and Mademoiselle Bourienne. Sonya and Natasha. Nikolai and Prince Andrei at the Front. Battle of Austerlitz. Andrei Wounded.) September 23 Volume Two, Parts One and Two, pp. 297-417 (1806. Nikolai Comes Home. Dinner for Bagration. Pierre and Dolokhov. The Duel. Princess Lise. Dolokhov and Sonya. Nikolai’s Gambling Loss. Denison’s Proposal. Pierre Becomes a Mason. Helene and Boris. Old Bolkonsky as Commander. Pierre and Emancipation of Serfs. Pierre and Andrei on Ferry Raft. Nikolai Rejoins his Regiment. Napoleon and Alexander as Allies.) September 30 Volume Two, Parts Three, Four, and Five, pp. 418-600 (1808-1812) Andrei Visits the Rostovs. Andrei, Speransky, and Arakhcheev . Pierre and Helene. Natasha and Andrei at the Ball. Engagement. Old Bolkonsky and Mlle Bourienne. Nikolai at Home. The Wolf Hunt. Natasha’s Dance. Christmas, Mummers, Fortune Telling. Pierre in Moscow. The Rostovs Call on the Bolkonskys.