Section 702 and the Collection of International Telephone and Internet Content

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Schrems II and Its Impact on the EU-US Privacy Shield

EU Data Transfer Requirements and U.S. Intelligence Laws: Understanding Schrems II and Its Impact on the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield March 17, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46724 SUMMARY R46724 EU Data Transfer Requirements and U.S. March 17, 2021 Intelligence Laws: Understanding Schrems II Chris D. Linebaugh and Its Impact on the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield Legislative Attorney On July 16, 2020, in a decision referred to as Schrems II, the Court of Justice of the European Edward C. Liu Union (CJEU) invalidated the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield (Privacy Shield). Privacy Shield is a Legislative Attorney framework developed by the European Union (EU) and the United States to facilitate cross- border transfers of personal data for commercial purposes. Privacy Shield requires companies and organizations that participate in the program to abide by various data protection requirements and, in return, assures the participants that the transfer is compliant with EU law. The CJEU, however, found Privacy Shield inadequate in part because it does not restrain U.S. intelligence authorities’ data collection activities. According to the CJEU, U.S. law allows intelligence agencies to collect and use the personal data transferred under the Privacy Shield framework in a manner that is inconsistent with rights guaranteed under EU law. The CJEU focused on Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, Executive Order 12333, and Presidential Policy Directive 28, which govern how the U.S. government may conduct surveillance of non-U.S. persons located outside of the United States. The CJEU’s Schrems II ruling has significant implications for personal data transfers between the EU and the United States. -

Through a PRISM, Darkly(PDF)

NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 Through a PRISM, Darkly Mark Rumold Staff Attorney, EFF NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 Electronic Frontier Foundation NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 What we’ll cover today: • Background; what we know; what the problems are; and what we’re doing • Codenames. From Stellar Wind to the President’s Surveillance Program, PRISM to Boundless Informant • Spying Law. A healthy dose of acronyms and numbers. ECPA, FISA and FAA; 215 and 702. NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 the background NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 changes technologytimelaws …yet much has stayed the same NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 The (Way) Background • Established in 1952 • Twin mission: – “Information Assurance” – “Signals Intelligence” • Secrecy: – “No Such Agency” & “Never Say Anything” NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 The (Mid) Background • 1960s and 70s • Cold War and Vietnam • COINTELPRO and Watergate NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 The Church Committee “[The NSA’s] capability at any time could be turned around on the American people and no American would have any privacy left, such is the capability to monitor everything. Telephone conversations, telegrams, it doesn't matter. There would be no place to hide.” Senator Frank Church, 1975 NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 Reform • Permanent Congressional oversight committees (SSCI and HPSCI) • Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) – Established requirements for conducting domestic electronic surveillance of US persons – Still given free reign for international communications conducted outside U.S. NANOG 59 – October 7, 2013 Changing Technology • 1980s - 2000s: build-out of domestic surveillance infrastructure • NSA shifted surveillance focus from satellites to fiber optic cables • BUT: FISA gives greater protection for communications on the wire + surveillance conducted inside the U.S. -

Summary of U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Law, Practice, Remedies, and Oversight

___________________________ SUMMARY OF U.S. FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE LAW, PRACTICE, REMEDIES, AND OVERSIGHT ASHLEY GORSKI AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION AUGUST 30, 2018 _________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS QUALIFICATIONS AS AN EXPERT ............................................................................................. iii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 I. U.S. Surveillance Law and Practice ................................................................................... 2 A. Legal Framework ......................................................................................................... 3 1. Presidential Power to Conduct Foreign Intelligence Surveillance ....................... 3 2. The Expansion of U.S. Government Surveillance .................................................. 4 B. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 ..................................................... 5 1. Traditional FISA: Individual Orders ..................................................................... 6 2. Bulk Searches Under Traditional FISA ................................................................. 7 C. Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act ........................................... 8 D. How The U.S. Government Uses Section 702 in Practice ......................................... 12 1. Data Collection: PRISM and Upstream Surveillance ........................................ -

April 11, 2014 Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board 2100 K St

April 11, 2014 Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board 2100 K St. NW, Suite 500 Washington, D.C. 20427 Re: March 19, 2014 Public Hearing Dear Chairman Medine and Board Members: The Constitution Project (TCP) welcomes this opportunity to comment on the March 19, 2014 public hearing and to offer our views on whether the federal government’s surveillance programs operated under the authority of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), 50 U.S.C. § 1881a, properly balance efforts to protect the Nation with the need to protect privacy and civil liberties. TCP is a non-profit think tank and advocacy organization that brings together unlikely allies—experts and practitioners from across the political spectrum—to develop consensus-based solutions to some of the most difficult constitutional challenges of our time. TCP’s bipartisan Liberty and Security Committee, comprised of former elected officials, former members of the law enforcement and intelligence communities, as well as legal academics, practitioners and advocates, previously made recommendations for statutory amendments to add warrant requirements and increase judicial and congressional oversight of Section 702 programs. See TCP’s September 2012 Report on the FISA Amendments Act. Liberty and Security Committee members convened following the PCLOB’s March 19, 2014 hearing, discussed the witness testimony and other newly available information, and agreed to reaffirm their previous policy on Section 702, with the following additional comments and recommendations.1 I. The Operation of Section 702 Our comments are supported by information about the operation of Section 702 recently revealed through declassified Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) opinions and leaks by National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden. -

NSA) Surveillance Programmes (PRISM) and Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) Activities and Their Impact on EU Citizens' Fundamental Rights

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT C: CITIZENS' RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS The US National Security Agency (NSA) surveillance programmes (PRISM) and Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) activities and their impact on EU citizens' fundamental rights NOTE Abstract In light of the recent PRISM-related revelations, this briefing note analyzes the impact of US surveillance programmes on European citizens’ rights. The note explores the scope of surveillance that can be carried out under the US FISA Amendment Act 2008, and related practices of the US authorities which have very strong implications for EU data sovereignty and the protection of European citizens’ rights. PE xxx.xxx EN AUTHOR(S) Mr Caspar BOWDEN (Independent Privacy Researcher) Introduction by Prof. Didier BIGO (King’s College London / Director of the Centre d’Etudes sur les Conflits, Liberté et Sécurité – CCLS, Paris, France). Copy-Editing: Dr. Amandine SCHERRER (Centre d’Etudes sur les Conflits, Liberté et Sécurité – CCLS, Paris, France) Bibliographical assistance : Wendy Grossman RESPONSIBLE ADMINISTRATOR Mr Alessandro DAVOLI Policy Department Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs European Parliament B-1047 Brussels E-mail: [email protected] LINGUISTIC VERSIONS Original: EN ABOUT THE EDITOR To contact the Policy Department or to subscribe to its monthly newsletter please write to: [email protected] Manuscript completed in MMMMM 200X. Brussels, © European Parliament, 200X. This document is available on the Internet at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/studies DISCLAIMER The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament. -

The Role of the Telecommunications Industry in Electronic Surveillance

Beyond Privacy and Security: The Role of the Telecommunications Industry in Electronic Surveillance Mieke Eoyang* INTRODUCTION On a Sunday in September 1975, a young lawyer on the Church Committee named Britt Snider drove to Maryland for a meeting with Dr. Lou Tordella, the retired civilian head of the National Security Agency (NSA). The Committee was investigating an NSA program codenamed SHAMROCK, which collected copies of all telegrams entering and exiting the United States. Tordella told Snider how every day, an NSA courier would hand carry reels of tape from New York to the NSA headquarters at Fort Meade. According to Tordella, all of the big international telegram carriers cooper- ated out of a sense of patriotism; they were not paid for their service. Snider suggested that the companies should have known that the government might abuse the situation to spy on American citizens. Tordella warned that the Committee’s exposure of the companies’ involvement could discourage them and others from cooperating with the government in the future. The companies received assurances from the Attorney General that their conduct was legal. They were nevertheless concerned and sought immunity from prosecution.1 This episode replayed itself half a century later, when the administration of George W. Bush assured private industry that its involvement in a questionable government surveillance program was perfectly legal. Surveillance experts often describe the balancing act between the interests of government and the interests of individuals. Frequently left out are the interests of private industry, without which electronic surveillance in the twenty-first century would be impossible. Government intelligence agencies rely on compa- nies who compete in a global market. -

Next Generation Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Law: Renewing 702

University of Richmond Law Review Volume 51 Issue 3 National Security in the Information Age: Are We Heading Toward Big Brother? Article 4 Symposium Issue 2017 3-1-2017 Next Generation Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Law: Renewing 702 William C. Banks Syracuse University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview Part of the Agency Commons, Law and Politics Commons, National Security Law Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation William C. Banks, Next Generation Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Law: Renewing 702, 51 U. Rich. L. Rev. 671 (2017). Available at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview/vol51/iss3/4 This Symposium Articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Richmond Law Review by an authorized editor of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEXT GENERATION FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE LAW: RENEWING 702 William C. Banks * Sometime before the end of 2017, Congress has to decide whether and then on what basis to renew the FISA Amendments Act ("FAA"),' a cornerstone authority for foreign intelligence sur- veillance that sunsets at the end of December 2017. The Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board ("PCLOB") reported in 2015 that more than one quarter of the National Security Agency (the "NSA") reports on terrorist activities are derived, in whole or in -

Mass Surveillance of Personal Data by EU Member States and Its

Mass Surveillance of Personal Data by EU Member States and its Compatibility with EU Law Didier Bigo, Sergio Carrera, Nicholas Hernanz, Julien Jeandesboz, Joanna Parkin, Francesco Ragazzi and Amandine Scherrer No. 62 / November 2013 Abstract In the wake of the disclosures surrounding PRISM and other US surveillance programmes, this paper assesses the large-scale surveillance practices by a selection of EU member states: the UK, Sweden, France, Germany and the Netherlands. Given the large-scale nature of these practices, which represent a reconfiguration of traditional intelligence gathering, the paper contends that an analysis of European surveillance programmes cannot be reduced to a question of the balance between data protection versus national security, but has to be framed in terms of collective freedoms and democracy. It finds that four of the five EU member states selected for in-depth examination are engaging in some form of large-scale interception and surveillance of communication data, and identifies parallels and discrepancies between these programmes and the NSA-run operations. The paper argues that these programmes do not stand outside the realm of EU intervention but can be analysed from an EU law perspective via i) an understanding of national security in a democratic rule of law framework where fundamental human rights and judicial oversight constitute key norms; ii) the risks posed to the internal security of the Union as a whole as well as the privacy of EU citizens as data owners and iii) the potential spillover into the activities and responsibilities of EU agencies. The paper then presents a set of policy recommendations to the European Parliament. -

US Technology Companies and State Surveillance in the Post-Snowden Context: Between Cooperation and Resistance Félix Tréguer

US Technology Companies and State Surveillance in the Post-Snowden Context: Between Cooperation and Resistance Félix Tréguer To cite this version: Félix Tréguer. US Technology Companies and State Surveillance in the Post-Snowden Context: Be- tween Cooperation and Resistance. [Research Report] CERI. 2018. halshs-01865140 HAL Id: halshs-01865140 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01865140 Submitted on 30 Aug 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License UTIC Deliverable 5 US Technology Companies and State Surveillance in the Post-Snowden Context: Between Cooperation and Resistance Author: Félix Tréguer (CERI-SciencesPo) 1 tech Executive Summary This deliverable looks at the growing hybridization between public and private actors in the field of communications surveillance for national security purposes. Focusing on US-based multinationals dominating the digital economy globally which became embroiled in the post-Snowden debates (companies like Google, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft, Yahoo), the report aims at understanding the impact of the Snowden scandal on the strategies of these companies in relation to state Internet surveillance. To that end, the report identifies seven factors that are likely to influence the stance of a given company and its evolution depending on the changing context and constraints that it faces across time and space. -

Protecting Personal Data, Electronic Communications, and Individual

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 42 Article 4 Number 3 Spring 2015 1-1-2015 The ewN Data Marketplace: Protecting Personal Data, Electronic Communications, and Individual Privacy in the Age of Mass Surveillance through a Return to a Property-Based Approach to the Fourth Amendment Megan Blass Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Megan Blass, The New Data Marketplace: Protecting Personal Data, Electronic Communications, and Individual Privacy in the Age of Mass Surveillance through a Return to a Property-Based Approach to the Fourth Amendment, 42 Hastings Const. L.Q. 577 (2015). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol42/iss3/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The New Data Marketplace: Protecting Personal Data, Electronic Communications, and Individual Privacy in the Age of Mass Surveillance Through a Return to a Property-Based Approach to the Fourth Amendment by MEGAN BLASS* I. Mass Surveillance in the New Millennium: Edward Snowden Versus The National Security Agency A. Watergate Fears Realized: National Security Agency Programs Exposed in 2013 Edward Snowden is now a household name.' He garnered global attention in 2013 when he claimed responsibility for leaking government documents that revealed unprecedented levels of domestic surveillance conducted by the National Security Agency ("NSA" or "the Agency"). 2 The information leaked by Mr. -

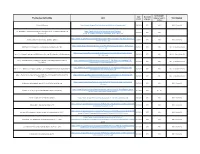

ICOTR Transparency Tracker

Subject matter Date Document category (used in Posting description/title Link posted orig. year Subcategory charts) Section 702 Overview https://www.dni.gov/files/icotr/Section702-Basics-Infographic.pdf 12/20/2017 2017 FISA FISA - Section 702 Fact Sheet: Guide to Posted Documents Regarding Use of National Security Authorities - Updated as of https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/icotr/Updated- 12/12/2017 2017 FISA December 2017 Guide_to_Posted_Documents_December_2017_FINAL.pdf https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/icotr/Updated-Guide-to-Section-702-Value-Examples--- Fact Sheet: Guide to Section 702 Value Examples - Updated 12/7/2017 2017 FISA FISA - Section 702 Dec-2017-FINAL.pdf https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/icotr/CLPT-USP-Dissemination-Paper---FINAL-clean- ODNI Report on Protecting U.S. Person Identities in Disseminations under FISA 11/20/2017 2017 FISA Title I, Title III, and Section 702 11.17.17.pdf https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/icotr/Annex-1-NSA-CLPO-Dissemination-Report- Annex 1 - The National Security Agency’s (NSA) Report on Protecting USP Information in FISA Disseminations 11/20/2017 2017 FISA Title I, Title III, and Section 702 20171027.pdf Annex 2 - The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Report on Protecting USP Information in FISA https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/icotr/Annex-2---FBI-Report-on-Protecting-USP- 11/20/2017 2017 FISA Title I, Title III, and Section 702 Disseminations Information-in-FISA-Disseminations.pdf https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/icotr/Annex-3---CIA-Report-on-Protecting-USP- Annex 3 - -

Reining in Warrantless Wiretapping of Americans

REPORT SURVEILLANCE & PRIVACY Reining In Warrantless Wiretapping of Americans MARCH 16, 2017 — JENNIFER GRANICK PAGE 1 The United States is collecting vast amounts of data about regular people around the world for foreign intelligence purposes. Government agency computers are vacuuming up sensitive, detailed, and intimate personal information, tracking web browsing,1 copying address books,2 and scanning emails of hundreds of millions of people.3 When done overseas, and conducted in the name of foreign intelligence gathering, the collection can be massive, opportunistic, and targeted without any factual basis. While international human rights law recognizes the political and privacy rights of all human beings, under U.S. law, foreigners in other countries do not enjoy free expression or privacy rights, so there are few rules and little oversight for how our government uses foreigners’ information. And while foreign governments are certainly legitimate targets for intelligence gathering, reported spying on international social welfare organizations like UNICEF and Doctors Without Borders raises the specter of political abuse without a clear, corresponding national security benefit.4 In my book, American Spies: Modern Surveillance, Why You Should Care, and What To Do About It,5 I explain the dangers that massive collection of information about Americans poses to our democracy. Soon, there will be an opportunity to rein in some of this surveillance. In December 2017, one of the laws enabling the National Security Agency (NSA) to warrantlessly wiretap Americans’ international communications and to gather foreigners’ private messages from top Internet companies will expire. The expiration forces Congress to decide whether to renew the law, reform it, or kill it.