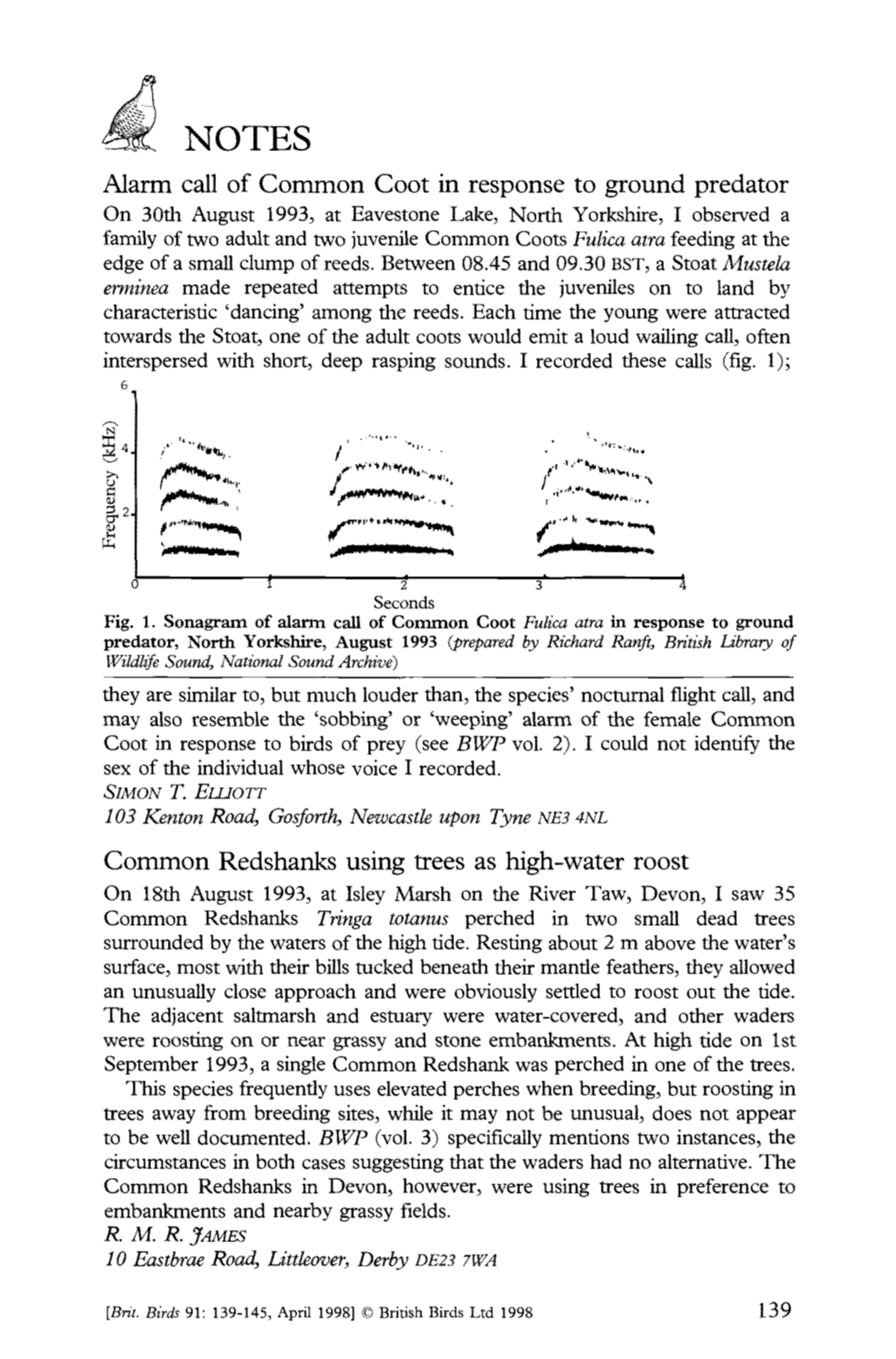

Alarm Call of Common Coot in Response to Ground Predator Common Redshanks Using Trees As High-Water Roost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Survey of Breeding Whinchats in Pembrokeshire 2012

A Survey of Breeding Whinchats in Pembrokeshire 2012. Paddy Jenks, Tansy Knight and Jane Hodges. Commissioned by Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority. 1 Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 4 Methods 6 Results 7 Current status 7 Productivity 11 Discussion 12 Current status and distribution 12 Potential Threats 13 Fire 13 Competition from Stonechats 13 Predation 14 Habitat management 15 Further study 16 References 17 2 Executive Summary The Whinchat Saxicola rubetra is a migrant breeding species favouring open country such as heathland, moorland, bogs, marshes and light scrub. The latest atlas of breeding birds in Pembrokeshire 2003-07 (Rees et al 2009) found that their distribution had been reduced by 70% in comparison to the 1984-1988 atlas. And this range contraction is accompanied by a 50% population decline. The species is currently amber listed and a local priority species. The aims of this survey are to record in detail the current breeding status and distribution of whinchats in Pembrokeshire, and to relate this distribution to habitat. This will lead to a greater understanding of habitat requirements and enable practical land management advice to aid their conservation within the PCNP. A set of sites where whinchats have bred in recent years within the PCNP were surveyed; St David’s Head, Dowrog, Fagwr Goch, Carn Ingli, Fronlas and Brynberian Moor. Several additional sites were visited on an ad hoc basis. These were; Pantmaenog, North Preseli east of Brynberian, Mynydd Crwn, Afon Wern. An initial visit was made to each of these sites between 20th May and 10th June and follow up visits were made between 19th June and 5th July. -

Whinchat Saxicola Rubetra in Sri Lanka in February 2015: First Record for the Island and the Indian Subcontinent

108 Indian BIRDS VOL. 13 NO. 4 (PUBL. 30 AUGUST 2017) Final Report submitted to the Ministry of Environment and Forests, New Delhi. 78–79. Mehta, P., Prasanna N. S., Nagar, A. K., & Kulkarni, J., 2015. Occurrence of Forest Owlet Raha, B., Gadgil, R., & Bhoye, S., 2017. Sighting of the Forest Owlet Heteroglaux blewitti Heteroglaux blewitti in Betul District, and the importance of its conservation in in Harsul, Nashik District, Maharashtra. Indian BIRDS 13 (3): 80–81. the Satpura landscape. Indian BIRDS 10 (6): 157–159. Rasmussen, P. C., & Collar, N. J., 1998. Identification, distribution and the status of the Mehta, P., & Kulkarni, J., 2014. Occupancy status of Forest Owlet in East and West Forest Owlet Athene (Heteroglaux) blewitti. Forktail 14: 43–51. Melghat Forest Division. Wildlife Research and Conservation Society. Final Ripley S. D., 1952. Vanishing and extinct bird species of India. Journal of Bombay Technical Report submitted to Maharashtra Forest Department. Natural History Society 50 (4): 902–906. Patel, J. R., Patel, S. B., Rathor, S. C., Patel, J. A., Patel, P. B., & Vasava, A. G., 2015. New Ripley S. D., 1976. Reconsideration of Athene blewitti (Hume). Journal of Bombay distribution record of the Forest Owlet Heteroglaux blewitti Hume, 1873, (Aves: Natural History Society 73 (1): 1–4. Strigiformes: Strigidae) in Purna Wildlife Sanctuary, Guarat, India. Journal of Shedke, S. D., & Kharinar, M. N., 2013. Management plan of Yawal Wildlife Sanctuary Threatened Taxa 7 (12): 7940–7944. (2012–13 to 2022–23). Maharashtra Forest Department. Patel, J., Vasava, A., & Patel, N., 2017. Occurrence of the Forest Owlet Heteroglaux Thompson, S., 1990. -

Paper Show Whinchat IV

WhinCHAT IV Paper show 2018 PaperPaper showshow 22019019 II`7`J`Y WGJ`-GWGJ`-G WWWJ`B GG On the following pages you will fi nd abstracts and summaries of new papers with a focus on Whinchats, mostly pu blished in 2019. English summaries are shown as available. Please help us to keep our “paper shows“ as complete as possible and send us abstracts of your newest publica ons (English preferred). Africa/Asia/Interna onal many Siberian Stonechats Saxicola maura Mancuso E, Toma L, Polci A, d’Alessio SG, Di present in the area, a prominent white su Luca M, Orsini M, Di Domenico M, Marcacci percilium and rela vely long wings piqued M, Mancini G, Spina F, Goff redo M, Monaco our curiosity. It had a buff streaked blackish F 2019: CrimeanCongo Hemorrhagic Fever face and crown, a strong white malar stripe, Virus Genome in Tick from Migratory Bird, and a bright orange throat and breast. The Italy. Emerging infec ous diseases 25.7, upperparts and rump were mo led dark, 14181420. DOI: h ps://doi.org/10.3201/ the tail was dark brown with white outer eid2507.181345 feathers. The bird was observed for 10–15 minutes and good photographs were taken They detected CrimeanCongo hemorrhagic (Plates 1,2). SO confi rmed that it was a male fever virus in a Hyalomma rufi pes nymph Whinchat Saxicola rubetra in breeding plu collected from a whinchat ( Saxicola rubet- mage. The Whinchat is a migratory pas ra ) on the island of Ventotene in April 2017. serine breeding in Europe and western Par al genome sequences suggest the virus Asia, east to the Ob river basin in Russia originated in Africa. -

4.3 Passerines If You Want to Increase Passerine 1 Birds on Your Moor, This Fact Sheet Helps You Understand Their Habitat and Diet Requirements

BD1228 Determining Environmentally Sustainable and Economically Viable Grazing Systems for the Restoration and Maintenance of Heather Moorland in England and Wales 4.3 Passerines If you want to increase passerine 1 birds on your moor, this fact sheet helps you understand their habitat and diet requirements. The species covered are the commoner moorland passerines that breed in England and Wales: • Meadow pipit • Skylark • Stonechat • Whinchat • Wheatear • Ring ouzel Broad habitat relationships The study examined detailed abundance relationships for the first five species and coarser presence/absence relationships for the last one above. Several other passerine species breed on moorland, from the widespread wren to the rare and highly localised twite, but these were not included in the study. Meadow pipit and skylark occur widely on moorlands, with the ubiquitous meadow pipit being the most abundant moorland bird. Wheatear, whinchat and stonechat are more restricted in where they are found. They tend to be most abundant at lower altitudes and sometimes on relatively steep ground. Wheatears are often associated with old sheepfolds and stone walls that are often used as nesting sites. The increasingly rare ring ouzel is restricted to steep sided valleys and gullies on moorland, often where crags and scree occur. They are found breeding from the lower ground on moorland, up to altitudes of over 800 m. Biodiversity value & status Of the moorland passerine species considered in this study: • Skylark and ring ouzel are red listed in the UK’s Birds of Conservation Concern • Meadow pipit and stonechat are amber listed in the UK’s Birds of Conservation Concern 1 Passerines are songbirds that perch 1 4.3 Passerines • Skylark is on both the England and Welsh Section 74 lists of the Countryside and Rights of Way Act of species the conservation of which will be promoted by the Governments [Note: Skylarks are red listed because of declines on lowland farmland largely, and stonechats are amber listed because of an unfavourable conservation status in Europe. -

Uganda Highlights

UGANDA HIGHLIGHTS JANUARY 11–30, 2020 “Mukiza” the Silverback, Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, January 2020 ( Kevin J. Zimmer) LEADERS: KEVIN ZIMMER & HERBERT BYARUHANGA LIST COMPILED BY: KEVIN ZIMMER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM UGANDA HIGHLIGHTS January 11–30, 2020 By Kevin Zimmer Shoebill, Mabamba wetlands, January 2020 ( Kevin J. Zimmer) This was the second January departure of our increasingly popular Uganda Highlights Tour, and it proved an unqualified success in delivering up-close-and-personal observations of wild Mountain Gorillas, wild Chimpanzees, and the bizarre Shoebill. Beyond these iconic creatures, we racked up over 430 species of birds and had fabulous encounters with Lion, Hippopotamus, African Elephant, Rothschild’s Giraffe, and an amazing total of 10 species of primates. The “Pearl of Africa” lived up to its advance billing as a premier destination for birding and primate viewing in every way, and although the bird-species composition and levels of song/breeding activity in this (normally) dry season are somewhat different from those encountered during our June visits, the overall species diversity of both birds and mammals encountered has proven remarkably similar. After a day at the Boma Hotel in Entebbe to recover from the international flights, we hit the ground running, with a next-morning excursion to the fabulous Mabamba wetlands. Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 Uganda Highlights, January 2020 Opportunistic roadside stops en route yielded such prizes as Great Blue Turaco, Lizard Buzzard, and Black-and-white-casqued Hornbill, but as we were approaching the wetlands, the dark cloud mass that had been threatening rain for the past hour finally delivered. -

Whinchat I Paper Show 2016

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: WhinCHAT - Digitale Magazine for Whinchat Research and Conservation Jahr/Year: 2016 Band/Volume: 1 Autor(en)/Author(s): diverse Artikel/Article: Paper show 2016 96-97 WhinCHAT I Paper show 2016 Paper show 2016 I WGJ`-G W G On the following pages you fi nd abstracts of new papers with „Whinchat in main focus“ published in 2016. The Bri sh papers can be found on the previous pages compiled by Jennifer Border. Interna onal The tested alterna ve mowing regimes may Broyer J, Sukhanova O, Mischenko A 2016: therefore locally increase popula on density How to sustain meadow passerine popula without nega ve density dependent eff ects ons in Europe through alterna ve mowing on hatching rates. Implemen ng rota onal management. Agriculture, Ecosystems & mowing could reduce habitat loss caused by Environment 215, 133139. farming abandonment in Russia. Postponing mowing un l a er midJuly in patches of hay Abstract: Two decades of agrienvironmental fi elds may sustain meadow bird demography policy did not prevent a long term decline of in the remaining strongholds of western Eu grassland birds in Europe. Addi onal mea rope. sures are therefore needed to sustain the popula ons. This study explored alterna ve Germany mowing management regimes likely to secu Feulner J, Rudroff S, Brendel U 2016: Ein re demographic sources in the early mown SchwarzkehlchenMännchen Saxicola tor- grassland systems of western Europe, and quata als Bruthelfer beim Braunkehlchen S. to limit habitat loss a er farming abandon rubetra. -

Survival and Development of Predator Avoidance in the Post-Fledging Period of the Whinchat (Saxicola Rubetra): Consequences

J Ornithol DOI 10.1007/s10336-011-0713-2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Survival and development of predator avoidance in the post-fledging period of the Whinchat (Saxicola rubetra): consequences for conservation measures Davorin Tome • Damijan Denac Received: 27 August 2010 / Revised: 14 April 2011 / Accepted: 4 May 2011 Ó Dt. Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V. 2011 Abstract Farmland bird populations in Europe are strategy, the current conservation measure (to postpone shrinking, largely due to modern agriculture practices. In mowing until the chicks in 80% of all nests have fledged) is grasslands, the shift to early mowing is believed to be not sufficient to halt population decline on improved particularly responsible for this decline because it is meadows. We suggest that at least 10 days more, and interwoven with breeding time—a change that birds in possibly even 14 days more, are necessary to maintain general have not adapted to. We studied the post-fledging viable Whinchat populations. survival of the Whinchat, an altricial grassland passerine. Based on a sample of 74 radiotagged young Whinchats, we Keywords Whinchat Á Saxicola rubetra Á Post-fledging confirmed that they fledge at 13–15 days. Twenty-four survival Á Mortality causes Á Conservation measures Á fledged birds died, while 18 of them were depredated. The Mowing regime survival probability of young Whinchats, calculated using Kaplan–Meier estimates, was lowest during the first day Zusammenfassung Die Praktiken in der modernen after fledging, and slowly leveled off later. In total, the Landwirtschaft fu¨hren in Europa zu einer Abnahme der probability that a juvenile survived the first month after Vogelpopulationen auf Ackerland. -

WHINCHAT Saxicola Rubetra Migrant Breeder/Passage Visitor 2003

WHINCHAT Saxicola rubetra Migrant breeder/passage visitor 2003 - Over 50 records were received from a wide selection of sites after the first at Whetstone quarry on 5th May. Breeding was confirmed at Timble Ings and was suspected on Barden Moor. Passage birds were noted at many locations including Otley Gravel Pits, Stockbridge, Beaverdyke and Fly Flatts Reservoirs, Cold Edge Dams, Windgate Nick, Trough Lane and Low Snowden. Most had departed by early September with the last record of a single at Beaverdyke Reservoir on 22nd. 2004 - First to arrive was a single at Trough Lane, near Oxenhope, on 20th April. After this, birds were reported widely but thinly from mainly moorland locations. The moors of Burley, Barden and Bingley were mentioned, as were the reservoirs of Leeshaw and Thornton Moor, in addition to Snowden Crags. Breeding was proved at White Wells, Norwood Lane and Cold Edge Dams. Autumn movement included up to seven at Cold Edge Dams in August, and eight in September, and up to six at Nab Water Lane, Wilsden. In the former month, a single at Otley Wetland was noteworthy. In September, various sites including Soil Hill and Paul Clough had up to three birds, with the latest record emanating from Thornton Moor Reservoir on 27th September. 2005 - Records in 2005 were in line with the pattern of recent years, with 47 reports from 19 sites, though it should be noted both are well down on those of ten years ago. The first bird was on Rombald’s Moor on 29th March, a relatively early date, which was emphasised by there being no further records until a month later, and only a few in the early part of May. -

The Birds of Wimbledon Common & Putney Heath 2016

The Birds of Wimbledon Common & Putney Heath 2016 Marsh Tit 1 The Birds of Wimbledon Common and Putney Heath 2016 The Birds of Wimbledon Common and Putney Heath 2016 here were 94 species recorded on the Common this year, 45 of which bred or probably bred. As T a matter of interest, the overall number of species recorded since records first began in 1974 currently stands at 152, nine of which being flyovers. This has been quite an exciting year on the Common, albeit with the usual ups and downs. There were three outstanding observations, in the form of Marsh Tit, European Bee-eater and Dartford Warbler, with the Marsh Tit providing the first positive evidence of breeding on the Common since 1979. My thanks are due to Jan Wilczur for his help in establishing this record; whilst the European Bee-eater seen and photographed on the 19th May by Magnus Andersson was even more remarkable, it being, according to the last sighting in the London Bird Report of 2007, possibly only the ninth to be recorded in the London area. And, last but not least, was the Dartford Warbler found at Ladies Mile on the 29th September, a bird which remained in the area until at least 19th Dec.; searching for previous records of this rare visitor, it would seem that this may have been the first record since 1938, a pair having bred in 1936. Other notable breeding species this year included the successful breeding of two pairs of Swallows, both nesting in out-buildings at the Windmill complex, one of which produced two broods; meanwhile three Willow Warbler territories were established, this being the best number since 2010, and at least two pair of Reed Buntings held territories. -

Völsgen - Whinchat in the Styrian Ennstal

WhinCHAT III Völsgen - Whinchat in the Styrian Ennstal Habitat requirements and popula on development of the Whinchat (Saxicola rubetra) in the Styrian Ennstal (Austria) S VY (StainachPürgg, Austria) VY S 2018: Habitat requirements and popula on development of the Whinchat ( Saxicola rubetra) in the Styrian Ennstal (Austria). Whinchat 3, 615. Habitatanspruch und Popula onsentwicklung des Braunkehlchens ( Saxicola rubetra) im Steirischen Ennstal (Österreich) Die Popula on des Braunkehlchens ( Saxicola rubetra) im Mi leren Ennstal (Steiermark) galt bis vor wenigen Jahren als eine der stabilsten in ganz Österreich. Die fortschreitende Intensivierung der Wiesenbewirtscha ung der letzten Jahr- zehnte gab Anlass zu einer fl ächendeckenden Erfassung der Braunkehlchenvorkommen in den Europaschutzgebieten von Admont bis Gröbming und dem Raum Bad Mi erndorf. Auf Grundlage von verschiedenen Erfassungen aus den Jahren von 2003 bis 2015 wurden die alten Fundpunkte und deren Umgebung auf Braunkehlchenvorkommen kontrol liert. Ergebnis der Kar erung ist ein Rückgang der Reviere um 90 % im zentralen Europaschutzgebiet („Ennstal zwischen Liezen und Niederstu ern“). Im ganzen Untersuchungsgebiet konnten 2016 insgesamt 14 Reviere festgestellt werden. In den besetzten Revieren (unterschieden wurde zwischen solchen mit und solchen ohne Bruterfolg) und auf Kontroll fl ächen, auf denen bei vorjährigen Erhebungen noch Reviere festgestellt werden konnten, wurden Habitatparameter erhoben, die poten ell einen Einfl uss auf Revierwahl und Bruterfolg haben könnten. Auf den Flächen mit Bruterfolg lagen eine signifi kant höhere strukturelle Vegeta onsdiversität und Anzahl an diesjährigen überstehenden Pfl anzen stängeln sowie ein höherer Grad an Bodenunebenheit vor. 50 % der Gelege wurden durch Mahd zerstört, was zeigt, dass im Gebiet der Zeitpunkt des ersten Mahdtermins der entscheidende Faktor für Bruterfolg ist. -

Scotland in Style

SCOTLAND IN STYLE MAY 1-10, 2020 ©2019 Please note this tour may be taken in connection with Wild & Ancient Britain with Ireland cruise , May 11-26, 2020. Cairngorms National Park © Andrew Whittaker This short, one hotel tour provides an enormously varied and comprehensive taste of all that the bonnie Scottish Highlands have to offer. During our seven full days based around Strathspey and the spectacular Cairngorms National Park, there will be a varied and flexible daily program of events. Although the main focus is on birding excursions, we will be centrally located to visit many fine castles, battlefields, and sites of historical significance, plus we’ll enjoy a guided visit to a famous Scotch single malt whisky distillery. Scotland in Style, Page 2 The Highlands scenery is the most dramatic in the British Isles: the highest peaks in Britain; extensive remote moorlands; large tracts of ancient woodland of Caledonian Pines; stunning coastal scenery of cliffs, inlets, lochs, and offshore islands; and vast tracts of prehistoric peat bog and fast-flowing, crystal clear rivers. We will target localized and rare specialties such as Eurasian Capercaillie (rare), Black Grouse, Rock Ptarmigan, Willow Ptarmigan (the British subspecies known as Red Grouse, an excellent candidate for a future split and another endemic), the gorgeous Mandarin Duck, the endemic Scottish Crossbill, localized Ring Ouzel, Crested Tit, Horned Grebe, Arctic and Red-throated loon, and raptors such as the striking Red Kite, Eurasian Sparrowhawk, Eurasian Buzzard, and Golden and White-tailed eagle (rare). Most of these breed only within the British Isles, exclusively here in this wild region of Scotland, and we have good chances of seeing most of them. -

11. Birds of the Paradise Gardens

Mute Swan Cygnus olor The mute swan is a species of swan, and thus a member of the waterfowl family Anatidae. It is native to much of Europe and Asia, and the far north of Africa. It is an introduced species in North America, Australasia and southern Africa Tundra Swan Cygnus columbianus The tundra swan is a small Holarctic swan. The two taxa within it are usually regarded as conspecific, but are also sometimes split into two species: Bewick's swan of the Palaearctic and the whistling swan proper of the Nearctic Bean Goose Anser fabalis The bean goose is a goose that breeds in northern Europe and Asia. It has two distinct varieties, one inhabiting taiga habitats and one inhabiting tundra Red-breasted Goose Branta ruficollis The red-breasted goose is a brightly marked species of goose in the genus Branta from Eurasia. It is sometimes separated in Rufibrenta but appears close enough to the brant goose to make this unnecessary, despite its distinct appearance Common Shelduck Tadorna tadorna The common shelduck is a waterfowl species shelduck genus Tadorna. It is widespread and common in Eurasia, mainly breeding in temperate and wintering in subtropical regions; in winter, it can also be found in the Maghreb Eurasian Teal Anas crecca The Eurasian teal or common teal is a common and widespread duck which breeds in temperate Eurasia and migrates south in winter Mallard Anas platyrhynchos The mallard or wild duck is a dabbling duck which breeds throughout the temperate and subtropical Americas, Europe, Asia, and North Africa, and has been introduced to New Zealand, Australia, Peru, ..