APPENDIX a Supreme Court of Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OJP Applicant Information Regarding Intergovernmental Reviews

OJP Applicant Information Regarding Intergovernmental Reviews This solicitation ("funding opportunity") is subject to Executive Order 12372. An applicant may find the names and addresses of State Single Points of Contact (SPOCs) below. If the applicant’s State appears on the SPOC list, the applicant must contact the State SPOC to find out about, and comply with, the State’s process under E.O. 12372. In completing the SF-424, an applicant whose State appears on the SPOC list is to make the appropriate selection in response to question 19 once the applicant has complied with its State E.O. 12372 process. (An applicant whose State does not appear on the SPOC list should answer question 19 by selecting the response that the “Program is subject to E.O. 12372 but has not been selected by the State for review.”) Intergovernmental Review (SPOC List) It is estimated that in 2009 the Federal Government will outlay $500 billion in grants to State and local governments. Executive Order 12372, "Intergovernmental Review of Federal Programs," was issued with the desire to foster the intergovernmental partnership and strengthen federalism by relying on State and local processes for the coordination and review of proposed Federal financial assistance and direct Federal development. The Order allows each State to designate an entity to perform this function. Below is the official list of those entities. For those States that have a home page for their designated entity, a direct link has been provided below by clicking on the State name. States that are not listed on this page have chosen not to participate in the intergovernmental review process, and therefore do not have a SPOC. -

Meeting Notice Oklahoma Firefighters Pension & Retirement Board 6601 Broadway Ext

MEETING NOTICE OKLAHOMA FIREFIGHTERS PENSION & RETIREMENT BOARD 6601 BROADWAY EXT. STE. 100 OKLAHOMA CITY, OK 73116 8:30 A.M. * FRIDAY* JULY 20, 2018 POSTED AGENDA The following items will be discussed and considered by the Board. It is anticipated that action may be taken on any item listed on the agenda, at the discretion of the Board. ROLL CALL: Matt Lay Jim Long Dereck Cassady Brandy Manek Eric Harlow Janet Kohls Craig Freeman Scott Vanhorn Buddy Combs Mike Kelley Dana Cramer Juan Rodriguez Cliff Davidson A) ELECTION OF CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD B) ELECTION OF VICE-CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD C) APPROVAL/MINUTES DATED JUNE 22, 2018. D) REQUEST APPROVAL/CONSENT AGENDA, COPY ATTACHED E) APPOINTMENT OF INVESTMENT AND RULES COMMITTEE F) GARCIA HAMILTON/JANNA HAMILTON & JEFFREY DETWILER – 8:35 A.M. G) ORLEANS/ GARY WELCHEL & PHYLLIS KYLE - 9:00 A.M. H) &CO CONSULTING/ TROY BROWN & TIM NASH 1. Presenting Manager Review. 1 I) INVESTMENT COMMITTEE/DERECK CASSADY – CHAIRMAN 1. Review BATTEA Class Action Services. 2. Review Investment Performance. 3. Review Hall Capital Real Estate Fund II. 4. Trustee Education. 5. Recommendation by Robbins Geller to seek lead plaintiff in a class action against Unum Group. 6. Recommendation by Berman Tobacco and Levi & Korsinsky to seek lead plaintiff in an action against Symantec Corporation. 7. Old Business. 8. New Business. J) STEVE RUTHER/ENID- REQUEST FOR HEARING 1. Executive Session if deemed necessary by Legal Counsel pursuant To 25 O.S. Section 307 B (1). 2. Vote to Enter into Executive Session. 3. Discussion on Administrative Hearing regarding application by Steve Ruther. -

Case 1:17-Cv-22652-KMW Document 142 Entered on FLSD Docket 06/10/2020 Page 1 of 40

Case 1:17-cv-22652-KMW Document 142 Entered on FLSD Docket 06/10/2020 Page 1 of 40 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA Case No. 17-22652-CIV-WILLIAMS DAVID M. RODRIGUEZ, Plaintiff, vs. THE PROCTER & GAMBLE COMPANY, Defendant. / ORDER THIS MATTER is before the Court on Defendant Procter and Gamble’s motion for summary judgment (DE 106). Plaintiff filed a response in opposition (DE 116) and Defendant filed a reply (DE 119). For the reasons discussed below, the motion (DE 106) is DENIED. I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND A. Plaintiff David Rodriguez In 1998, Plaintiff David Rodriguez (“Rodriguez”), a Venezuelan native, entered the United States on a tourist visa at age 14. (DE 104-2 at 10-11.) Rodriguez fled Venezuela to escape the increasing violence from the attempted coups led by Hugo Chavez. (Id. at 9.) His family, fearful of the political situation and concerned for his safety, had encouraged him to leave the country. (Id.) Upon arriving to the United States, Rodriguez lived with an aunt and cousin in Kendall, a neighborhood in Miami-Dade County, Florida. (Id. at 11-12.) Since then, Rodriguez has remained in South Florida and has never 1 Case 1:17-cv-22652-KMW Document 142 Entered on FLSD Docket 06/10/2020 Page 2 of 40 returned to Venezuela; he considers himself as having “[grown] up here in the United States” and as being “from the United States.” (Id. at 15, 183.) Plaintiff graduated from the magnet school, G. Holmes Braddock Senior High School in 2002, and for a few years before college, he worked in restaurants, tutored students, and took on “odd jobs.” (Id. -

Con Safos --A Chicano's Journey Through Life in California

798 CON SAFOS --A CHICANO'S JOURNEY THROUGH LIFE IN CALIFORNIA Trip to the Kangaroo Court: Southwest --Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, El Paso 1983 I was commanded by the high muckety mucks of the American GI Forum to attend the 1983 national conven tion at El Paso, Texas so they could have a Kangaroo Court and throw me out of the organization. n the orders of Joe Cano, national chair man; and Louis Tellez, national executive 0 secretary; both very sad excuses for offic- ers of a national organization purporting to be a civil rights group, but that is another story, for another chap ter elsewhere. I decided to take the scenic route to El Paso. It might be the last chance we would ever have to see parts of this country that we had never seen. Most of our long trips involved going to and from the Ameri can GI Forum national convention, and if they were going to throw me out, this might be the last long trip of our lives. I had always wanted to drive across the desert from Reno to Salt Lake City, and here was the opportunity. I could tell by looking at maps that there was very little or nothing between Wendover, Utah and Salt Lake City but fl at ground, salt, and sagebrush. And in some areas, not even sagebrush. A thought which crossed my mind as I looked across the desert after leaving Wendover was that it might be very easy for a person with criminal intentions to 0o-e t the idea that way out here in the desert, he could just about do anything to anyone and get away with it. -

July 2008 Chapman Tornado Adds Real-World Mission to Annual Training by Spc

Embedded Manhattan hit Final gunnery Training by tornado; training is Team back Guard rushes bittersweet PPllhomeaa . i.i . n.n . .2 ss GGto helpuu a.a . .10rrddiiaa . n.n . .19 Volume 51 No. 3 Serving the Kansas Army and Air National Guard, Kansas Emergency Management, Kansas Homeland Security and Civil Air Patrol July 2008 Chapman tornado adds real-world mission to annual training By Spc. Jessica Rohr, 105th MPAD On June 11, 2008, at approximately “Being a National Guard 11:30 p.m. Chapman, Kan., was rocked by Soldier doesn’t just mean a devastating tornado that cut a swath through the town, injuring several people that you get called into a and killing at least one. combat zone when the big Nearby, at Fort Riley, the 1st Battalion, Army is short. You do a lot 161st Field Artillery was wrapping up a successful annual training exercise. Once more here at home than the storm passed and all was calm, the people realize.” Soldiers of the battalion were called into Sgt. Matthew Weller action to aid the rescue workers headed toward Chapman for the first 48 hours. The magnitude seemed higher because it The crew of 19 was led by Capt. Dave was the entire town pretty much that was Quintanar and Capt. Dana Graf Jr. The gone since it was so small.” Soldiers and nine humvees rushed to the Before starting their shift, Wright escort- scene, where they quickly integrated with ed Quintanar and Weller on a tour of the local law enforcement, firefighters and impacted area. During this informative emergency personnel. -

Alumni 2006-5.Indd

Alumni Newsletter February 2006 Price: A Smile EEXPERIENCESXPERIENCES TTHATHAT SHAPESHAPE THETHE FFUTUREUTURE Deploy Me to Camp: Military Scholarship Program PAGE 9 From the USSR, to the USA: Camp Webstore Goes Online The Experience of a Soviet Counselor PAGE 11 PAGE 10 Visit the 800.242.1909 NEW www.lincoln-lakehubert.com A new year and a new beginning! he Summer of 2006 marks Camp’s 97th year on the pristine Tshores of Minnesota’s Lake Hubert. That’s 97 years old and The “Alumni Railsplitter” is published 97 years strong. The tradition of excellence at Camp Lincoln WELCOME annually by Camp Lincoln and Camp & Camp Lake Hubert continues as we embrace and prepare Lake Hubert and distributed free for another summer of legendary camping...inTENTional of charge to all Camp Lincoln and camping. That is, a summer camp experience in which everything Camp Lake Hubert Alumni, including is done with a purpose and an expected outcome for each goal. We former campers and staff, in addition believe that by being an Intentional Camp, we are able to provide to current campers and staff. Please send address corrections to the absolute best experience for campers, parents and staff. Camp Lincoln/Camp Lake Hubert; In today’s world, more than ever, we consider it a true privilege to have a positive impact on the lives 10179 Crosstown Circle; Eden Prairie, MN 55344. of hundreds of campers each summer. We realize how time flies as we watch our young Gopher and Happy Hollow campers progress to become Seniors and LT’s in the blink of an eye. -

City of Newberry

City of Newberry City Commission Agenda Item Meeting Date: January 25, 2016 Title: Acceptance of Settlement Agreement between United States of America et al. ex rel Perez v. Stericycle Inc. Agenda Section: VIII. C. Department: Legal Presented By: S. Scott Walker Recommended Action: Hold on recommendation for further legal research Summary: In 2009, then Fire Chief David Rodriguez executed an Agreement with Stericycle, Inc. for collection and transport of regulated medical waste. This Agreement was not approved by the City Manager or the City Commission. The original cost per pick up in 2009 was $82.00. Over time, that cost increased to $417.52 per pickup as recently as June 2015. Chief Ben Buckner was concerned about this high price and researched alternatives that were substantially lower. Chief Buckner attempted negotiations with Stericycle, but Stericycle was unresponsive. This culminated in a letter to Stericycle dated June 9, 2015 from the City that the Agreement was never approved by the Commission, and further, the Commission never approved the increase in billed amount. After several more emails regarding the same, Stericycle stopped picks up for the City of Newberry, and stopped sending invoices late in 2015 On July 23, 2013, litigation was filed against Stericycle on behalf of the United States and several states, including the state of Florida. The litigation was filed pursuant to the Federal False Claims Act, and several other state acts, including the Florida False Claims Act. The Plaintiffs argued Stericycle overcharged customers through the use of impermissible fuel and energy surcharges, and automatic price increases without authorization. -

746447 3479.Pdf

Case 16-07207-JMC-7A Doc 3479 Filed 06/24/19 EOD 06/24/19 19:18:18 Pg 1 of 773 Case 16-07207-JMC-7A Doc 3479 Filed 06/24/19 EOD 06/24/19 19:18:18 Pg 2 of 773 EXHIBIT A ITT EducationalCase Services, 16-07207-JMC-7A Inc., et al. - U.S. Mail Doc 3479 Filed 06/24/19 EOD 06/24/19 19:18:18 Pg 3 Servedof 773 6/18/2019 1-290 LIMITED PARTNERSHIP 1-290 LIMITED PARTNERSHIP 1-290 LIMITED PARTNERSHIP ATTN: ERIC J. TAUBE ATTN: RICK DUPONT C/O WALLER LANSDEN DORTCH & DAVIS LLP 100 CONGRESS AVE, STE 1800 3508 FAR WEST BLVD, SUITE 100 ATTN: ERIC J. TAUBE AUSTIN, TX 78701 AUSTIN, TX 78731 100 CONGRESS AVE, STE 1800 AUSTIN, TX 78701 200 BOP LL, LLC 200 BOP LL, LLC 220 WEST GERMANTOWN LLC ATTN: GRIFFITH PROPERTIES LLC C/O DAIN, TORPY, LE RAY, WIEST & GARNER, PC ATTN: SUSAN FRIEDMAN 260 FRANKLIN ST, 5TH FLR. ATTN: MICHAEL J. MCDERMOTT 397 KINGSTON AVE BOSTON, MA 02110 745 ATLANTIC AVE, 5TH FLR. BROOKLYN, NY 11225 BOSTON, MA 0211 220 WEST GERMANTOWN LLC 2525 SHADELAND LLC 26500 NORTHWESTERN, LLC. C/O BALLARD SPAHR LLP C/O PLUNKETT COONEY ATTN: ARI KRESCH ATTN: CHRISTINE BARBA, ESQ. ATTN: DAVID A. LERNER, ESQ 26700 LAHSER RD, STE 400 1735 MARKET ST 38505 WOODWARD AVE , STE 2000 SOUTHFIELD, MI 48033 51ST FL BLOOMFIELD HILLS, MI 48304 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19103 2GRAND MEDIA 311 NEW RODGERS ASSOCIATES LLC 311 NEW RODGERS ASSOCIATES LLC 6956 NAVIGATION DR C/O KRIEG DEVAULT LLP C/O LASSER HOCHMAN LLC GRAND PRAIRIE, TX 75054 ATTN: KAY DEE BAIRD, ESQ ATTN: RICHARD L. -

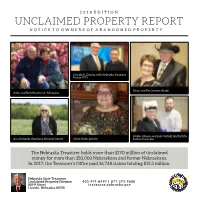

Unclaimed Property Report Notice to Owners of Abandoned Property

2018 EDITION UNCLAIMED PROPERTY REPORT NOTICE TO OWNERS OF ABANDONED PROPERTY Tom Rock, Omaha, with Nebraska Treasurer Photo by KETV Karen and Ken Sawyer, Brady Ardys and Herb Roszhart Jr., Marquette Walter Johnson and Josh Gartrell, North Platte Ann Zacharias Grosshans, Nemaha County Alicia Deats, Lincoln Photo by Tammy Bain The Nebraska Treasurer holds more than $170 million of unclaimed money for more than 350,000 Nebraskans and former Nebraskans. In 2017, the Treasurer’s Office paid 16,748 claims totaling $15.3 million. Nebraska State Treasurer Unclaimed Property Division 402-471-8497 | 877-572-9688 809 P Street treasurer.nebraska.gov Lincoln, Nebraska 68508 Tips from the Nebraska State Treasurer’s Office Filing a Claim If you find your name on these pages, follow any of these easy steps: • Complete the claim form and mail it, with documentation, to the Unclaimed Property Division, 809 P Street, Lincoln, NE 68508. • For amounts under $500, you may file a claim online at treasurer.nebraska.gov. Include documentation. • Call the Unclaimed Property Division at 402-471-8497 or 1-877-572-9688 (toll free). • Stop by the Treasurer’s Office in Suite 2005 of the Capitol or the Unclaimed Property Division at 809 P Street in Lincoln’s Haymarket. Hours are 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday. Recognizing Unclaimed Property Unclaimed property comes in many shapes and sizes. It could be an uncashed paycheck, an inactive bank account, or a refund. Or it could be dividends, stocks, or the contents of a safe deposit box. Other types are court deposits, utility deposits, insurance payments, lost IRAs, matured CDs, and savings bonds. -

Academic Excellence Banquet Awards & Dinner April 4, 2017 6:00 P.M

Welcome to the Center High School 2016-2017 AcAdemic excellence BAnquet Awards & Dinner April 4, 2017 6:00 p.m. Center School District would like to thank Blue cross Blue shield heAlthcAre of KAnsAs city for generously sponsoring this event, including the dinner following the awards presentation. Schedule of Events Principal’s introduction Mrs. Sharon Ahuna, Principal introduction of Guest sPeAKer Mrs. Kathy Chirpich Guest sPeAKer Dr. Shatonda S. Jones, Ph.D., CCC-SLP, Asst Professor of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Rockhurst University and 1999 Center Graduate freshmen scholArs Mrs. Sharon Ahuna, Principal soPhomore scholArs Mrs. Krista McGee, Assistant Principal Junior scholArs Mr. Troy Butler, Assistant Principal senior scholArs Mr. Jonathan Dandurand, Teacher AcKnowledGements Mr. Joe Nastasi, Board of Education President dinner cAtered By BrAncAto’s cAterinG Proprietor: Mario Brancato, Center High School Class of 1976 freshmAn soPhomores Sarah Asher Bailey Calvin Analynn Bullock Jaevyn Carson Gabriel Calvin Rayanna Dial David Clarkson Gracious Ford Brownlee Kimberly Cook Jordan Glover Joseph Ezeugo NaAliah Griffith Holly Gerry Lashawn Handson Alex Gomez-Gonzales Jillian Kramschuster Reina Gray Christian McDonald Xander Hacking Elasah Quinn Molly Hake Trevor Rey LeAsia Harrell Dereck Richardson ShaRiya Hendrix Christian Ricketts Ariana Hernandez Ethan Robertson Brock Howerton Savannah Simpson Jasmine Maqsood Kathryn Tanner Ashly Mota-Perez Audrey Tsafack Zane Parker Deontre Winston David Rodriguez Casey Rose Siraj Shah Azandrea Wilson-Hancock Juniors Shelby Bass Ciante Miller Cierra Britt Abbie Nastasi Justin Clubine Sierra Reed Trezmond Jackson Terrannie Scott Julian Kiwinda Alexis Simpson Duncan MacDonald Joelleanne Tejada Bethany Miller Mia Washington JessicA cruz-Bello Jessica Cruz Bello has strengthened the Center commu- nity with her academic excellence since kindergarten. -

Case 2:15-Cv-00889-JCH-SMV Document 190 Filed 03/13/17 Page 1 of 46

Case 2:15-cv-00889-JCH-SMV Document 190 Filed 03/13/17 Page 1 of 46 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW MEXICO PHILLIP O. LOPEZ and FELIZ GONZALES, Plaintiffs v. No. 2:15-CV-00889 JCH/SMV THE STATE OF NEW MEXICO, THE CITY OF LAS CRUCES, and OFFICER DAVID RODRIGUEZ and DETECTIVE MICHAEL RICKARDS, in their official and individual capacities as employees of the City of Las Cruces, Defendants. MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER This matter comes before the Court on the following motions: (i) Plaintiff Feliz Gonzales’s Motion for Partial Summary Judgment against Defendants City and Rodriguez (ECF No. 28); (ii) Plaintiff Phillip Lopez’s Motion for Partial Summary Judgment against Defendants City and Rodriguez (ECF No. 131); and (iii) Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment Based on Qualified Immunity and Governmental Immunity (ECF No. 138). The Court, having considered the motions, briefs, evidence, and relevant law, concludes that Plaintiffs’ motions will be denied and Defendants’ motion will be granted in part and denied in part. I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND1 On the evening of January 4, 2015, Officer David Rodriguez was on duty as a police officer for the City of Las Cruces. Defs.’ Resp. to Pl. Lopez’s Mot. for Summ. J., Undisputed Fact (“UF”) ¶ 1, ECF No. 143. He was dispatched on a non-emergency, non-domestic disturbance call to an address at 624 West Court Road regarding a dispute and threats between 1 Many of the facts are undisputed. Where a dispute of fact exists, the Court will set forth the respective parties’ version of events, as supported in the record. -

"I Support the City of Santa Fe's Memorial to Recognize Same-Sex Marriages As Legal in New Mexico. Sign Me up As a Citizen

Dear Mayor David Coss, We are pleased to present you with this petition affirming one simple statement: "I support the City of Santa Fe's memorial to recognize same-sex marriages as legal in New Mexico. Sign me up as a citizen co-sponsor of this important civil rights legislation." Attached is a list of individuals who have added their names to this petition, as well as additional comments written by the petition signers themselves. Sincerely, Pat Davis 1 Sign me up as a citizen co-sponsor for legalizing same-sex marriage By Pat Davis (Contact) To be delivered to: Mayor David Coss Petition Statement: I support the City ofSanta Fe's memorial to recognize same-sex marriages as legal in New Mexico. Sign me up as a citizen co-sponsor ofthis important civil rights legislation. Petition Background The City of Santa Fe is introducing a resolution, complete with a legal opinion, declaring that same-sex marriage in New Mexico is officially legal. The legal opinion, drafted by City Attorney Geno Zamora, notes: 1) New Mexico's laws do not define marriage as between a man and a woman-the definitions are gender-neutral; 2) A statutory list of prohibited marriages does not list same-sex couples; 3) Same-sex marriages from other states are already recognized by New Mexico law; 4) To discriminate against same-sex couples would violate the New Mexico Constitution which requires equality under the law regardless of sex. It encourages county clerks to immediately issue legal same-sex marriage licenses. The resolution is sponsored by Mayor Coss and Councilor Bushee.