Uteroplacental Vasculature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doppler Velocimetry of the Uteroplacental Circulation

Chapter 16 Doppler Velocimetry of the Uteroplacental Circulation Edwin R. Guzman, Eftichia Kontopoulos, Ivica Zalud Introduction blood flow at term was estimated at 500±700 ml/min with a two- to threefold decrease in uteroplacental Since the last edition of this volume, interest has con- perfusion noted in the presence of preeclampsia. tinued in uterine artery Doppler velocimetry (UADV) Uterine artery Doppler velocimetry was first re- as a screening technique to predict adverse pregnancy ported by Campbell and colleagues in 1983 [10]. They outcomes such as preeclampsia, for pregnancy risk showed that, compared to pregnancies with normal scoring, and as an entry criterion for randomized uterine artery waveforms, pregnancies with abnormal trials on medical therapies for the prevention of pre- uterine artery Doppler waveforms were associated with eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. These more proteinuric hypertension, required more antihy- areas have been updated and UADV for predicting pertensive therapy, and resulted in lower birth weights pregnancy outcome in medical conditions other than and younger gestational ages at birth. Thus the capabil- preeclampsia has been added. The areas regarding ity for this potentially safe, noninvasive, prospective non-Doppler assessment of uterine artery flow, phys- means of analyzing uterine artery blood flow during iology and development of uterine artery flow, and pregnancy was realized and set off a wave of interest the development of uterine artery Doppler waveform and research that has continued until today. remain essential and have been retained for historical purposes. Anatomy of Uterine Circulation Non-Doppler Methods The uterine artery originates from the internal iliac to Measure Uterine Artery Blood Flow artery and meets the uterus just above the cervix. -

Proceedings Of

MODEL BASED ASSESSMENT OF SYSTEMIC AND UTERINE CIRCULATION CONTRIBUTION TO AN ABNORMAL UTERINE ARTERY DOPPLER Shivbaskar Rajesh and Sanjeev G. Shroff Department of Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh INTRODUCTION properties are not the sole determinants of an abnormal UAD In present day obstetrics, the Uterine Artery Doppler (UAD) waveform; the generalized maternal systemic arterial is a noninvasive sonography method used to measure the uterine dysfunction may play a significant role. The first success artery blood flow in pregnant women with the goal of criterion for this project is to develop a baseline model that characterizing the state of placentation and fetal blood supply. produces physiologically realistic pressure and flow waveforms UAD generates waveforms to monitor the velocity of blood at different systemic arterial locations. For example, the average flowing through the uterine artery. An abnormal UAD pressure that we expect to see in the ascending aorta and femoral waveform, representing the failure of proper gestational artery is around 97 mmHg, while the average flow in the adaptations, is associated with high-risk for pregnancy ascending aorta and femoral artery is 83 and 4 ml/s, respectively. complications or adverse fetal outcome such as preeclampsia or We will strive to have our model-based outputs within 5% of the fetal growth restriction (FGR) [1]. physiological values obtained from the literature. In normal pregnancy, vascular adaptations occur in the maternal body to help accommodate the placenta and fetus. METHODS Blood volume, heart rate, and cardiac output increase, while the The baseline model was built using Matlab/Simulink and vascular resistance decreases. Within the uterine circulation, the PLECS simulation software, and it is based on several validated endovascular extravillous and interstitial trophoblast cells models of the human circulatory system. -

Sapporo Medical University 2004 – 2009

RESEARCH ACTIVITIES OF SAPPORO MEDICAL UNIVERSITY 2004 – 2009 Hokkaido,Japan March 2010 RESEARCH ACTIVITIES OF SAPPORO MEDICAL UNIVERSITY 2004 – 2009 Edited by Committee for International Affairs and Medical Exchanges Sapporo Medical University Toshikazu Saito Neuropsychiatry, School of Medicine Shin Morioka English, Center for Medical Education Hiroki Takahashi Internal Medicine ( III ), School of Medicine Tsuyoshi Saito Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine Michiaki Yamakage Anesthesiology, Center for Medical Education Makoto Nemoto Liberal Arts and Sciences (English), School of Health Sciences Kimiharu Inui Applied Physical Therapy , Schhl of Health Sciences Contents ΣޓOUTLINE OF SAPPORO MEDICAL UNIVERSITYȤȤ!ȁ2 ޓޓޓޓޓPediatrics ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȁ78 ޓ㧝ޓOUTLINE ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤ!ȁ3 ޓޓޓޓޓOphthalmology ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȁ7: ޓޓޓޓޓDermatology ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȁ82 ޓ㧞ޓORGANIZATION ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤ!ȁ6 ޓޓޓޓޓUrology ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȁ84 ޓޓޓޓOrganization ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤ!ȁ6 ޓޓޓޓޓOtolaryngology ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȁ86 ޓޓޓޓNumber of Teaching Staffs & Fellows ȤȤȤȤȤ!ȁ9 ޓޓޓޓޓNeuropsychiatry ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȁ88 ޓޓޓޓNumber of Students ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤ!ȁ: ޓޓޓޓޓRadiology ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȁ8: ޓޓޓޓޓAnesthesiology ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȁ92 ΤޓRESEARCH ACTIVITIES ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤ!!22 ޓޓޓޓޓCommunity and General Medicine ȤȤȤȤȤȁ94 ޓ㧭ޓSCHOOL OF MEDICINE ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤ!!23 ޓޓޓޓޓClinical Laboratory Medicine ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȁ96 ޓޓ㧝ޓMedical Sciences ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȁ23 ޓޓޓޓޓTraumatology and Critical Care Medicine ȤȤȤȁ98 ޓޓޓޓޓObstetrics and Perinatal Medicine ȤȤȤȤȤȤȁ23 ޓޓޓޓޓOral Surgery ȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȤȁ9: ޓޓޓޓޓPlastic -

Normal and Abnormal Transformation of the Spiral Arteries During Pregnancy

Article in press - uncorrected proof J. Perinat. Med. 34 (2006) 447–458 • Copyright ᮊ by Walter de Gruyter • Berlin • New York. DOI 10.1515/JPM.2006.089 Normal and abnormal transformation of the spiral arteries during pregnancy Jimmy Espinoza1,2, Roberto Romero1,3,*, Yeon Keywords: Atherosis; immunohistochemistry; impe- Mee Kim1,4, Juan Pedro Kusanovic1, Sonia dance to blood flow; integrin; physiologic transformation Hassan1,2, Offer Erez1, Francesca Gotsch1, of the spiral arteries; placental bed. Nandor Gabor Than1, Zoltan Papp5 and Chong Jai Kim1,4 1 Perinatology Research Branch, NICHD, NIH, DHHS, Anatomy and physiology of the uterine Detroit MI 48201, and Bethesda MD 20892, USA circulation 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Wayne The blood supply of the uterus is provided by the uterine State University School of Medicine, Detroit MI 48201, and ovarian arteries w102x. After entering the myome- USA trium, the uterine arteries give rise to the ‘‘arcuate arter- 3 Center for Molecular Medicine and Genetics, Wayne ies,’’ which branch into the ‘‘radial arteries’’ w102x. The State University School of Medicine, Detroit MI 48201, radial arteries divide into the ‘‘basal arteries,’’ which sup- USA ply the basal portion of the endometrium (critical for 4 Department of Pathology, Wayne State University endometrial regeneration after menstruation) and the School of Medicine, Detroit MI 48201, USA ‘‘spiral arteries,’’ which continue toward the endometrial 5 First Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, surface w95x. The term ‘‘spiral arteries’’ reflects the coiled Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary appearance of these vessels, whose role is to supply blood to the upper functional layer of the endometrium, thought to be shed during menstruation w95x. -

Transformation of the Spiral Arteries in Human Pregnancy: Key Events in the Remodelling Timeline

Placenta 32, Supplement B, Trophoblast Research, Vol. 25 (2011) S154eS158 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Placenta journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/placenta IFPA Gabor Than Award lecture: Transformation of the spiral arteries in human pregnancy: Key events in the remodelling timeline L.K. Harris* Maternal and Fetal Health Research Group, University of Manchester, UK article info abstract Article history: During human pregnancy, the uterine spiral arteries are progressively remodelled to form dilated Accepted 23 November 2010 conduits lacking maternal vasomotor control. This phenomenon ensures that a constant supply of blood is delivered to the materno-fetal interface at an optimal velocity for nutrient exchange. Conversion of Keywords: a tonic maternal arteriole composed of multiple layers of vascular smooth muscle, elastin and numerous Artery other extracellular matrix components, into a highly dilated yet durable vessel, requires tight regulatory Decidua control and the coordinated actions of multiple cell types. Initial disruption of the vascular wall, char- Elastin acterised by foci of endothelial cell loss, and separation and misalignment of vascular smooth muscle EVT fl Extracellular matrix cells (VSMC), is coincident with an in ux of uterine natural killer (uNK) cells and macrophages. uNK cells Invasion are a source of angiogenic growth factors and matrix degrading proteases, thus they possess the capacity Leukocytes to initiate changes in VSMC phenotype and instigate extracellular matrix catabolism. However, complete Macrophages vascular cell loss, mediated in part by apoptosis and dedifferentiation, is only achieved following colo- Myometrium nisation of the arteries by extravillous trophoblast (EVT). EVT produce a variety of chemokines, cytokines Remodelling and matrix degrading proteases, enabling them to influence the fate of other cells within the placental Trophoblast bed and complete the remodelling process. -

And Fetoplacental Arterial Vascular Resistance in Enos-Deficient Mice Due to Impaired Arterial Enlargement1

BIOLOGY OF REPRODUCTION (2015) 92(2):48, 1–11 Published online before print 17 December 2014. DOI 10.1095/biolreprod.114.123968 Site-Specific Increases in Utero- and Fetoplacental Arterial Vascular Resistance in eNOS-Deficient Mice Due to Impaired Arterial Enlargement1 Monique Y. Rennie,4,5 Anum Rahman,4,5 Kathie J. Whiteley,8 John G. Sled,2,3,4,5 and S. Lee Adamson3,6,7,8 4Mouse Imaging Centre, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 5Department of Medical Biophysics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 6Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 7Department of Physiology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 8Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION The sites of elevated vascular resistance that impede placental Placental vascular defects underlie some of the most perfusion in pathological pregnancies are unknown. In the current common and severe pregnancy complications, but the specific study, we identified these sites in a knockout mouse model location of those vascular defects remains unclear. Preeclamp- (eNOSÀ/À) with reduced uterine (À55%) and umbilical (À29%) sia is thought to stem from blunted uteroplacental vessel artery blood flows caused by endothelial nitric oxide synthase dilation and failure of the spiral arteries to be transformed into deficiency. Uteroplacental and fetoplacental arterial vascular wide flaccid tubes [1–3]. Intrauterine growth restriction Downloaded from www.biolreprod.org. trees of pregnant mice near term were imaged using x-ray (IUGR) is thought to stem from a hypovascular fetoplacental microcomputed tomography (n ¼ 5–10 placentas from 3–5 dams/ tree [4, 5]. -

June 04, 2021 Fast Super-Resolution Ultrasound Microvessel Imaging

Ultrasound localization microscopy (ULM) June 04, Fast super-resolution ultrasound microvessel imaging using has been proposed to image 2021 spatiotemporal data with deep fully convolutional neural network microvasculature beyond the ultrasound diffraction limit. Pregnancy is a unique physiological state January A Protocol for Evaluating Vital Signs and Maternal-Fetal in which two individuals coexist: the 04, 2021 Parameters Using High-Resolution Ultrasound in Pregnant Mice mother and the fetus. Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is January Pharmacological inhibition of Notch signaling regresses pre- characterized by transmural infiltration of 01, 2019 established abdominal aortic aneurysm myeloid cells at the vascular injury site. A decline in capillary density and blood January Impairment of an Endothelial NAD + -H 2 S Signaling Network Is a flow with age is a major cause of mortality 01, 2018 Reversible Cause of Vascular Aging and morbidity. Abdominal aortic aneurysms are January Development and growth trends in angiotensin II-induced murine pathological dilations that can suddenly 01, 2018 dissecting abdominal aortic aneurysms rupture, causing more than 15,000 deaths in the U.S. annually. Disruption of vulnerable atherosclerotic August 24, Ultraselective Carbon Nanotubes for Photoacoustic Imaging of plaques often leads to myocardial 2021 Inflamed Atherosclerotic Plaques infarction and stroke, the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the We presently show that sEH knockout repressed nicotine-induced arterial August 24, Soluble epoxide hydrolase deletion attenuated nicotine-induced stiffness and extracellular matrix 2021 arterial stiffness via limiting the loss of SIRT1 remodeling via SIRT1-induced YAP deacetylat Fish protein consumption exerts Anti-atherogenic effect of 10% supplementation of anchovy August 24, beneficial metabolic effects on human (Engraulis encrasicolus) waste protein hydrolysates in apoe- 2021 health, also correlat-ing with a decreased deficient mice risk for cardiovascular disease. -

Uterine Natural Killer Cells Initiate Spiral Artery Remodeling in Human Pregnancy

The University of Manchester Research Uterine natural killer cells initiate spiral artery remodeling in human pregnancy DOI: 10.1096/fj.12-210310 Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Robson, A., Harris, L. K., Innes, B. A., Lash, G. E., Aljunaidy, M. M., Aplin, J. D., Baker, P. N., Robson, S. C., & Bulmer, J. N. (2012). Uterine natural killer cells initiate spiral artery remodeling in human pregnancy. Faseb Journal, 26(12), 4876-4885. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.12-210310 Published in: Faseb Journal Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:06. Oct. 2021 Uterine natural killer cells initiate spiral artery remodelling in human pregnancy A Robson1,4; LK Harris2,4; BA Innes1; GE Lash1; MM Aljunaidy2; JD Aplin2; PN Baker2,3; SC Robson1; JN Bulmer1,5 5 1Reproductive and Vascular Biology Group, Institute of Cellular Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; 2Maternal and Fetal Health Research Centre, University of Manchester, UK; 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta. -

2 DMA’S Most Anticipated One Liners 1

Anatomy 1 Authors: M.Balakrishnana, S.Sakthivel & Roshan Akthar www.dmaedu.com www.dmaedu.com 2 DMA’s Most Anticipated One Liners 1. Father of modern anatomy: Andreus vesalius 2. Cartilage has no blood vessels and nerves 3. Artery : thick walled, has smaller lumen 4. Veins : thin walled, has larger lumen 5. Lateral thyroid develops from 4th pharyngeal pouch 6. Trapezius is supplied by spinal part of accessory nerve 7. Rotator cuff muscles: Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, Teres minor and Subscapularis 8. Dupytren contracture: 9. Knee joint is the largest and most complex joint of the body inflammation of ulnar side of palmar aponeurosis 10. Typical ribs are ribs 3-9 11. Atypical ribs are ribs 1,2,10,11,12 12. Inspiration is an active process and expiration is a passive process 13. Deep fascia of penis: Buck’s fascia 14. Deep fascia of thigh: Fascia lata 15. Nerve of laterjet is a branch of vagus nerve (present in stomach) 16. Arnold’s nerve is a branch of vagus nerve 17. Esophagus pierces the diaphragm at the level of 10th vertebra 18. Peyer’s patches are seen in Ileum 19. Stylopharyngeus muscle is a muscle of the 3rd pharyngeal arch 20. Risorius is the ‘Grinning muscle’ 21. Notochord Develops Into nucleus pulposus 22. Most frequently fractured bone in the body is clavicle 23. Azygous means unpaired 24. Midgut is supplied by SMA (superior mesenteric artery) 25. Length of small intestine is 6 metres 26. Length of thoracic duct is 45 cms 27. Left testicular vein drains into Left renal vein & Right testicular vein drains into IVC Uterine artery is a branch of Internal Iliac artery (IIA) 28. -

Uteroplacental Vasculature

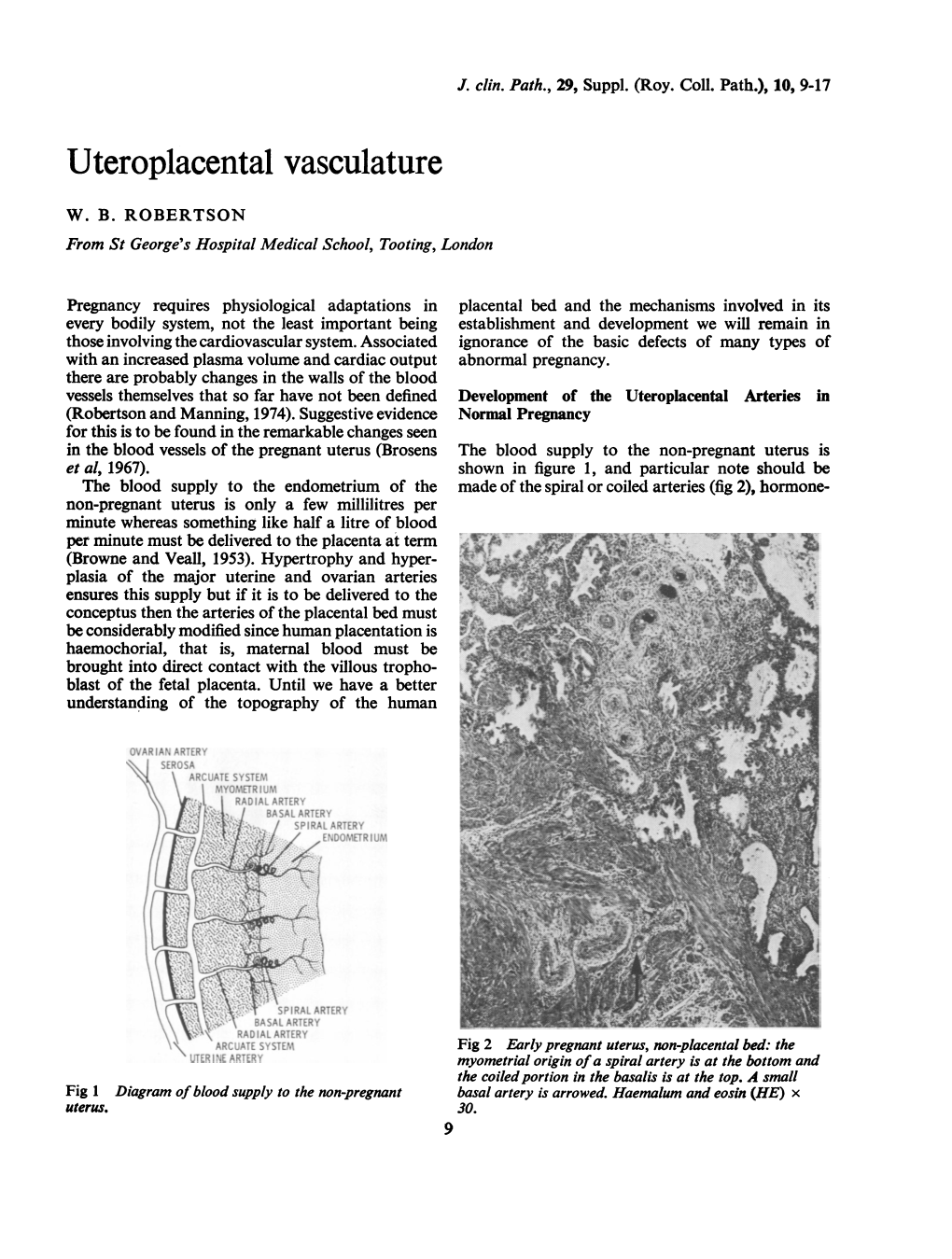

J Clin Pathol: first published as 10.1136/jcp.s3-10.1.9 on 1 January 1976. Downloaded from J. clin. Path., 29, Suppl. (Roy. Coll. Path.), 10, 9-17 Uteroplacental vasculature W. B. ROBERTSON From St George's Hospital Medical School, Tooting, London Pregnancy requires physiological adaptations in placental bed and the mechanisms involved in its every bodily system, not the least important being establishment and development we will remain in those involving the cardiovascular system. Associated ignorance of the basic defects of many types of with an increased plasma volume and cardiac output abnormal pregnancy. there are probably changes in the walls of the blood vessels themselves that so far have not been defined Development of the Uteroplacental Arteries in (Robertson and Manning, 1974). Suggestive evidence Normal Pregnancy for this is to be found in the remarkable changes seen in the blood vessels of the pregnant uterus (Brosens The blood supply to the non-pregnant uterus is et al, 1967). shown in figure 1, and particular note should be The blood supply to the endometrium of the made of the spiral or coiled arteries (fig 2), hormone- non-pregnant uterus is only a few millilitres per minute whereas something like half a litre of blood per minute must be delivered to the placenta at term (Browne and Veall, 1953). Hypertrophy and hyper- plasia of the major uterine and ovarian arteries ensures this supply but if it is to be delivered to the conceptus then the arteries of the placental bed must be considerably modified since human placentation is haemochorial, that is, maternal blood must be brought into direct contact with the villous tropho- blast of the fetal placenta. -

Bstetric Anesthesia Handbook Fourth Edition O BSTETRIC ANESTHESIA HANDBOOK Fourth Edition Sanjay Datta, MD, FFARCS (Eng)

O bstetric Anesthesia Handbook Fourth Edition O BSTETRIC ANESTHESIA HANDBOOK Fourth Edition Sanjay Datta, MD, FFARCS (Eng) Professor of Anesthesia Brigham and Women’s Hospital Harvard Medical School Boston, Massachusetts With 72 Illustrations Sanjay Datta, MD, FFARCS (Eng) Professor of Anesthesia Brigham and Women’s Hospital Harvard Medical School Boston, MA 02115 USA Library of Congress Control Number: 2005926767 ISBN 0-387-26075-7 ISBN 978-0387-26075-4 Printed on acid-free paper. © 2006 Springer Science+Business Media, Inc. Third edition © 2000 by Hanley & Belfus, Inc All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, Inc., 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. While the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of going to press, neither the author nor the editor nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. The publisher makes no war- ranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein. -

Walsh University

Walsh University Effects of Reduced Uterine Perfusion Pressure on Cerebral Artery Tone in Pregnant Rats Treated with Nanoparticles Containing VEGF Receptor A Thesis by Matthew D. Thomas Mathematics and Sciences Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Bachelor of Science Degree with University Honors May 2016 Accepted by the Honors Program Jacqueline Novak, Ph.D., Advisor Date Adam Underwood, Ph.D., Reader Date Ty Hawkins, Ph.D., Honors Director Date Acknowledgments I would like to offer a special thanks to Dr. Jackie Novak and Dr. J.J. Ramirez for graciously sharing their time and knowledge and their persistent patience. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. Adam Underwood for being the reader of this thesis and his assistance in the lab. I would like to thank Dr. Ty Hawkins, Dr. Koop Berry, and Walsh University’s Honors program for the wonderful opportunity to grow intellectually and personally. Lastly, I would like to thank my family for their continued support throughout this entire process. iv Table of Contents Figures, Tables, and Graphs………………………………….………….....…..………v Abstract and Introduction……………………………….….…………………….……1 Literature Review………..…………….………….…………………………..……...…4 Purpose……………………………………………...…….….…………………….……13 Methodology………………………………..…………….….…………………….……14 Results……………………………………………………….….………………….……26 Discussion……………………………………………..….….…………………….……37 Limitations……………………………………………….….…………………….……40 Conclusion……………………………………………….….……………………..……41 References……………………………….….…………………………….……….……42 Appendix………………………...……………………….….……………………...….A-1